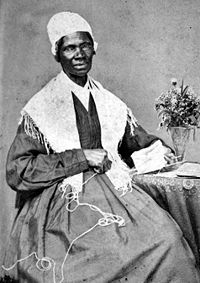

Sojourner Truth

Sojourner Truth (circa. 1797–1883) was a slave who became famous for being an American abolitionist. She was a self-proclaimed Evangelist, who changed her name based on a revelation she received in 1843.

She was born Isabella Bomefree (later changed to Baumfree) in the Dutch settlement of Hurley in upstate New York. Born into a large slave family she was sold four different times before finding freedom.

The painful experiences of being a child, wife, and mother who had to endure slavery and her personal religious experiences formed a personality that made her a courageous advocate for slaves and an avid supporter of women's rights as well.

Despite the fact that she could not read or write, she won three different court cases against whites in her lifetime and became a respected and influential public speaker.

Early Life

Born to James and Betsey Baumfree, Isabella's family was owned by the Dutch-speaking Johannes Hardenbergh, who operated a gristmill and owned a substantial amount of property. He had been a member of the New York colonial assembly and a colonel in the Revolutionary War. Because the Hardenbergh's were a Dutch-speaking family, Isabella spoke only Dutch as a small child. She is believed to have had anywhere from 10 to 13 brothers and sisters. The records are unclear because many were sold away.

In 1799, Johannes Hardenbergh died and Isabella became the slave of his son, Charles Hardenbergh. When Isabella was around nine years old her new master died and her mother and father were both freed due to their old age. However, Isabella and her younger brother were put up for auction. She was sold for $100 to John Neely, a man who owned a store near the village of Kingston. She rarely saw her parents after this time.

During her time with the Neely's she received many severe whippings for not responding to orders. Her only crime was that she did not speak English and therefore did not understand their commands. After two years with the Neely's, she was sold to Martinus Schryver, a fisherman who lived in Kingston. In 1810, at the age of 13, she became the property of John Dumont. She worked for him for 17 years. Dumont had a small farm and only a few slaves. While working on Dumont's farm, Isabella was praised for being hard working. According to Isabella, Dumont was a humane master who only whipped her once when she tormented a cat.

Around 1816, Isabella married Tom, another slave owned by Dumont. He was older than Isabella and had already been married two times before. They had five children together.

In 1799, New York adopted a law that gradually abolished slavery. According to the law, on July 4, 1827, all slaves within the state would be freed. When Dumont reneged on a promise to free Tom and Isabella on July 4, 1826, she left the Dumont farm with only her infant daughter a few months later. Leaving Tom and three other children behind, she walked several miles to the house of Levi Roe, a Quaker. Roe told her to go to the home of Isaac and Maria Van Wagenen who lived in Wahkendall. The Van Wageners bought her from Dumont when he showed up wanting her back and then freed her.

Fighting for her rights

Unlike those who fled from southern slavery, Isabella was able to remain in her home state as a free woman. While denied full citizenship rights in that state, one of the first things she did after obtaining her freedom was to sue for the freedom of her son Peter. Her six-year-old son Peter had been given away as a present to Sally Dumont's sister. The sister's husband decided to sell Peter to a man that then illegally sold him to Alabama. (New York, as part of the law that was gradually eradicating slavery, refused to allow slaves in New York be sold to any other state, in order that these residents of the state would indeed gain their freedom as the designated date.) When Isabella learned that her son had been sold the Van Wagenen's suggested that she hire a lawyer and sue, and helped her raise the funds to pay the lawyer. She won the case and her son was returned to her. This would be the first of three court cases she would eventually win.

After winning the case she and Peter traveled to New York City to find work as servants to wealthy families. Mr. and Mrs. Latourette were her first employers. During this time she was able to experience a reunion with some of her sisters and a brother who was sold before she was born. It was also her first experience of a black community—something completely non-existent in the rural areas where she had lived.

Religious Life

During the time she spent with the Van Wagenens, she underwent a religious experience that began her transformation to becoming Sojourner Truth. According to her dictated autobiography, one day "God revealed himself to her, with all the suddenness of a flash of lightning, showing her, 'in the twinkling of an eye, that he was all over,' that he pervaded the universe, 'and that there was no place where God was not.'"

When she first moved to New York in 1829 she attended a class for Negroes at the John Street Methodist Church, but later she joined the A.M.E. Zion Church on Church and Leonard Street. She began preaching occasionally at this time, telling the story of her conversion, and singing her story to listeners.

In the early 1830s, Isabella began to work for a Mr. Pierson. Her employer thought he was a re-incarnation of Elijah from the Bible and his home and the group he led were known as "The Kingdom." He developed a relationship with Robert Matthews, who imagined himself, the Second Coming of Christ, and called himself the Prophet Matthias.[1] This was a time of self-styled religious prophets and these men developed a following that included Isabella. She ended up moving with them to an estate in Western New York, where they tried an experiment in communal living. When Mr. Pierson died suspiciously, the entire group found themselves splashed all over the newspapers—Matthews was accused of murder and Isabella was accused of poisoning two of the members. Matthews was acquitted of the murder (although he did spend some months in prison for beating his daughter.) Isabella was also acquitted, and successfully sued the couple that accused her for slander.

After this experience she returned briefly to New York and again worked as a servant. But it wasn't long before she decided to leave New York City. On June 1, 1843, she gathered together a few belongings that she could easily carry and before long she set out on her own singing her story to revival groups, and becoming a popular preacher. It was about this time also that she received a revelation from God to call herself Sojourner Truth.

In 1844, still liking the utopian cooperative ideal, she joined the Northampton Association of Education and Industry in Massachusetts. This group of 210 members lived on 500 acres of farmland, raising livestock, running grist and saw mills, and operating a silk factory. Unlike the Kingdom, the Association was founded by abolitionists to promote cooperative and productive labor. They were strongly anti-slavery, religiously tolerant, women's rights supporters, and pacifist in principles. While there, she met and worked with abolitionists such as William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglass, and David Ruggles. Unfortunately, the community's silk-making was not profitable enough to support itself and it disbanded in 1846 amid debt.

In 1850, she decided to tell her story to Olive Gilbert, a member of the Northhampton Association, and it was published privately by William Lloyd Garrison as Narrative of Sojourner Truth: A Northern Slave. The popularity of Frederick Douglass' book about his journey to freedom gave her hope that her book might earn enough money to permit her to purchase a home of her own. More importantly, she wanted to tell the story of a northern slave.

She went around the northern states, selling her book, and telling her life story. In 1851, she spoke at the Women's Rights convention in Akron, Ohio, and gave a stirring speech on behalf of women—this became known as the Ain't I a Woman?[2] speech, denouncing the idea of feminine fragility. In 1858, at a meeting in Silver Lake, Indiana, someone in the audience accused her of being a man (she was around six feet) so she opened her blouse to reveal her breasts.

She once visited the house of Harriet Beecher Stowe while several well-known ministers were there. When asked if she preached from the Bible, Truth said no, because she couldn't read. "When I preaches," she said, "I has just one text to preach from, an' I always preaches from this one. My text is, 'When I found Jesus'."

Sojourner later became involved with the popular Spiritualism religious movement of the time, through a group called the Progressive Friends, an offshoot of the Quakers. The group believed in abolition, women's rights, non-violence, and communicating with spirits. In 1857, she sold her home in Northampton and bought one in Harmonia, Michigan (just west of Battle Creek), to live with this community.

Later Life

During the American Civil War, she organized the collection of supplies for the Union, and moved to Washington, D.C. after the Emancipation Proclamation was issued, to work with former slaves. Working for the Freedman's Bureau, she taught newly freed slaves the skills they would need to be successful. Almost 100 years before Rosa Parks, Sojourner Truth also fought for the right to ride the streetcars in Washington, DC and won.

By the end of the Civil War, Truth had met with Abraham Lincoln, had her arm dislocated by a racist streetcar conductor and won a lawsuit against him, spoke before Congress petitioning the government to make western lands available to freed blacks, and made countless speeches on behalf of African Americans and women.

She returned to Michigan in 1867 and died at her home in Battle Creek, Michigan, on November 26, 1883. She is purported to have said towards the end, "I'm goin' home like a shootin' star." In 1869, she gave up smoking her clay pipe. A friend had once admonished her for the habit, telling her the Bible says that "no unclean thing can enter the Kingdom of Heaven." When she was asked how she expected to get into Heaven with her smoker's bad breath she replied, "When I goes to Heaven I expects to leave my bad breath behind."

She is buried in Oak Hill Cemetery in Battle Creek. In 1890, Frances Titus, who published the third edition of Sojourner's Narrative in 1875 and was a traveling companion of hers, collected money and erected a monument on the gravesite, inadvertently inscribing "aged about 105 years." She then commissioned artist Frank Courter to paint the meeting of Sojourner and President Lincoln.

In 1983, Sojourner Truth was inducted into the Michigan Women's Hall of Fame in 1983.[3].

Notes

- ↑ The Matthias Delusion, The World Wide School, 1999. Retrieved February 5, 2008

- ↑ Sojourner Truth (1797-1883): Ain't I A Woman?, Paul Halsall, 1997. Retrieved February 5, 2008.

- ↑ Michigan Women's Hall of Fame, Michigan Women's Historical Center and Hall of Fame. Retrieved October 9, 2015.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Encyclopædia Britannica Truth, Sojourner. Encyclopædia Britannica Online Library Edition, 2006.

- Mabee, Carleton. Sojourner Truth: Slave, Prophet, Legend. New York University Press, 1993. ISBN 0814755259

- McKissack, Patricia C. Sojourner Truth: Ain't I A Woman Scholastic Paperbacks, 1994. ISBN 0590446916

- Painter, Nell Irvin, Sojourner Truth: A Life, a Symbol. W.W. Norton, 1996. ISBN 0393317080

- Pauli, Hertha Ernestine. Her Name Was Sojourner Truth. Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1962. ISBN 0380007193

- Rockwell, Ann. Only Passing Through: the Story of Sojourner Truth. Knopf, 2000. ISBN 0679891862

External links

All links retrieved January 30, 2023.

- On the trail of Sojourner Truth

- Sojourner Truth Institute

- Address to Equal Rights Association

- The Avalon Project

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.