Rosa Parks

Rosa Louise McCauley Parks (February 4, 1913 – October 24, 2005) was an African-American civil rights activist whom the U.S. Congress dubbed the "Mother of the Modern-Day Civil Rights Movement."

Mrs. Parks is one of the two individuals most often associated with the Civil Rights Movement in the South during the 1960s, along with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. She is famous for her refusal on December 1, 1955 to obey bus driver James Blake's demand that she give up her seat to a white passenger. Her subsequent arrest and trial for this act of civil disobedience triggered the Montgomery Bus Boycott, one of the largest and most successful mass movements against racial segregation in history, and launched Martin Luther King, Jr., one of the organizers of the boycott, to the forefront of the Civil Rights Movement. Her role in American history earned her an iconic status in American culture, and her actions have left an enduring legacy for civil rights movements around the world. Mrs. Parks determined to fight for equality and resolution of oppression through peaceful, nonviolent, resistance. She understood that the necessity of maintaining her dignity through her public ordeals was crucial, as her stance was not for herself alone but on behalf of her entire race.

Her role in the bus boycott has been the subject of debate. In the popular version, she was described as a "tired seamstress" on her way home from work, refusing to give up her seat on the bus. The true story of Mrs. Parks might more accurately be as described by Diane McWorther in A Dream of Freedom: “The tired she felt was the kind of fatigue of the soul that has built for decades and finally sets off a revolution.”

Certainly her act of resistance set in motion an irreversible cycle of change that would eventually secure equal treatment under the law for all African-Americans. Wrote Richette L. Haywood in Jet Magazine:

"For those who lived through the unsettling 1950s and 1960s and joined the civil rights struggle, the soft-spoken Rosa Parks was more, much more than the woman who refused to give up her bus seat to a White man in Montgomery, Alabama. Hers was an act that forever changed White America's view of Black people, and forever changed America itself." [1]

Early years

Rosa Parks was born Rosa Louise McCauley in Tuskegee, Alabama on February 4, 1913 to James and Leona McCauley, a carpenter and a teacher. When her parents separated, she moved with her mother to Pine Level, Alabama, just outside Montgomery. There she grew up on a farm with her maternal grandparents, mother, and younger brother Sylvester, and began her lifelong membership in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Her mother homeschooled Rosa until she was eleven, when she enrolled in the Industrial School for Girls in Montgomery, taking academic and vocational courses. Parks then went on to a laboratory school set up by the Alabama State Teachers College for Negroes (now Alabama State University) for secondary education, but was forced to drop out to care for her grandmother, and later for her mother, after she too grew ill.

Marriage

In 1932, Rosa married Raymond Parks, a barber from Montgomery, at her mother's house. Raymond was a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and at the time was collecting money to support the Scottsboro Boys, a group of black men falsely accused of raping two white women. After her marriage, Rosa took a number of jobs, ranging from domestic worker to hospital aide. At her husband's urging, she finished her high school studies in 1933, at a time when less than seven percent of African-Americans had a high school diploma.

In December 1943, Parks became active in the Civil Rights Movement, joining the Montgomery chapter of the NAACP, and was elected volunteer secretary to its president, Edgar Nixon. She would continue as secretary until 1957. In the 1940s, Parks and her husband were also members of the Voters' League. Sometime soon after 1944, she held a job briefly at Maxwell Air Force Base, where federal rules prohibited racial segregation, commuting on an integrated trolley. Mrs. Parks later stated, "You might just say Maxwell opened my eyes up."

She also worked as a housekeeper and seamstress for a white couple, Clifford and Virginia Durr. In the summer of 1955, the politically liberal Durrs became her friends, and encouraged Parks to attend, eventually helping to sponsor her at the Highlander Folk School, an education center for workers' rights and racial equality in Monteagle, Tennessee. Highlander was known throughout the South as a radical educational center planning methods that would see the total desegregation of the South. While at the school, Rosa determined to become an active participant in other attempts to break down the barriers of segregation.[2]

Early Influences

Under Jim Crow laws, Americans of European descent and those of African descent were segregated in virtually every aspect of daily life in the South, including public transportation and public facilities. Parks recalled going to elementary school in Pine Level, where school buses took white students to their new school while black students walked to theirs: "I'd see the bus pass every day… But to me, that was a way of life; we had no choice but to accept what was the custom. The bus was among the first ways I realized there was a black world and a white world."

Though Parks' autobiography recounts that some of her earliest memories are of the kindness of white strangers, her situation made it impossible to ignore racism. When the Ku Klux Klan marched down the street in front of her house, Parks recalls her grandfather guarding the front door with a shotgun. The Montgomery Industrial School, founded and staffed by white Northerners for black children, was burned twice by arsonists, and its faculty was ostracized by the white community.

Like many, Parks was deeply moved by the brutal murder of Emmett Till in August 1955. On November 27, 1955, only four days before her famous refusal to give up her seat on the bus, she attended a meeting in Montgomery which focused on the Till case as well as the recent murders of George W. Lee and Lamar Smith. The featured speaker at the meeting was T.R.M. Howard, a black civil rights leader from Mississippi who headed the Regional Council of Negro Leadership.

Civil rights activism

Many people today have no concept of legalized, institutionalized racism, organized racist groups, and personal hatreds faced by African Americans that created a need for a liberation movement. The story of oppression must be told as part of the true story of freedom. The story must be told of the risk and courage of the African Americans who originated the struggle for civil rights in the United States as well as the history and nature of segregation.[2]

Events leading up to boycott

In 1944, athletic star Jackie Robinson took a stand in a confrontation with an Army officer in Fort Hood, Texas, refusing to move to the back of a bus. He was brought before a court-martial, which acquitted him.[3] The NAACP had accepted and litigated other cases before, such as that of Irene Morgan ten years earlier, which resulted in a victory in the U.S. Supreme Court on Commerce Clause grounds. That victory, however, overturned state segregation laws only insofar as they applied to travel in interstate commerce, such as interstate bus travel.

A boycott had been discussed as far back as 1949 by the Woman’s Political Council (WPC). WPC was a black women’s group which was working for full integration, not simply “better seating arrangements.” The boycott came about through collective decision making, willed risk and coordinated action; not simply by an angry individual who sparked a demonstration.[2]

African-American leaders had prepared for years to stage a bus boycott due to the treament of blacks on the bus. The community in Montgomery were ready to support the boycott, they were just waiting for word from community leaders. Others had been arrested before Mrs. Parks, but each had to be carefully scrutinized; the NAACP understood that whoever they chose to stand behind would have to withstand the pressures of cross-examination in a legal challenge to racial segregation laws. Because of her integrity and leadership within the civil rights movement, Rosa Parks became the figurehead. She was well-known to all of the African American leaders in Montgomery for her opposition to segregation, her leadership abilities and her moral strength. Since 1954 and the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, she had been working on the desegregation of the Montgomery schools.

The day she was arrested the leadership called a meeting at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. They decided to begin their refusal to ride the buses the very next morning. They knew Mrs. Parks had the courage to deal with the pressure of defying segregation and would not yield even if her life was threatened. The next day the boycott began.

Bus protest and arrest

In Montgomery, public buses were divided into two sections, one at the front for Caucasian Americans, meant for whites only. From five to ten rows back the section for African Americans began, which was called the colored section. When it was crowded on city buses, blacks were forced to give up seats in the colored sections to whites and move to the back of the bus. Black passengers had to pay their bus fare in the front, then get off the bus, walk to the back door and enter that way to find their seat. They could not simply walk from the front to the back after paying their fare. For years, the black community had complained that the situation was unfair, and Parks was no exception: "My resisting being mistreated on the bus did not begin with that particular arrest…I did a lot of walking in Montgomery."

On December 1, 1955, after a day at work at Montgomery Fair department store, Parks boarded the Cleveland Avenue bus in downtown Montgomery. She paid her fare and sat in an empty seat in the first row of back seats reserved for blacks in the "colored" section. As the bus traveled along its regular route, all of the white-only seats in the bus filled up. The bus reached the stop in front of the Empire Theater, and several white passengers boarded. Following standard practice, the bus driver demanded that four black people give up their seats in the middle section so that the white passengers could sit. Years later, in recalling the events of the day, Parks said,

"When that white driver stepped back toward us, when he waved his hand and ordered us up and out of our seats, I felt a determination cover my body like a quilt on a winter night."

Rosa acted with clear resolve to keep her seat despite being told otherwise. It was not a matter of simple fatigue after one tiring day. Not mere anger or stubbornness; she was confronting segregation head on with whatever sacrifice she had to make.

During a 1956 radio interview with Sydney Rogers in West Oakland, when asked why she had decided not to vacate her bus seat, Parks said, "I would have to know for once and for all what rights I had as a human being and a citizen of Montgomery, Alabama."

Parks also detailed her motivation in her autobiography, My Story

"People always say that I didn't give up my seat because I was tired, but that isn't true. I was not tired physically, or no more tired than I usually was at the end of a working day. I was not old, although some people have an image of me as being old then. I was forty-two. No, the only tired I was, was tired of giving in."

When Parks refused to give up her seat, a police officer arrested her. As the officer took her away, she recalled that she asked, "Why do you push us around?" The officer's response as she remembered it was, "I don't know, but the law's the law, and you're under arrest." She later said, "I only knew that, as I was being arrested, that it was the very last time that I would ever ride in humiliation of this kind."

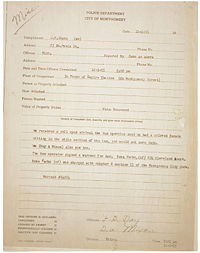

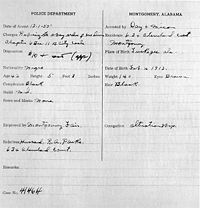

Parks was charged with a violation of Chapter 6, Section 11 segregation law of the Montgomery City code, even though she technically had not taken up a white-only seat; she had been in a colored section. E.D. Nixon and Clifford Durr bailed Parks out of jail the evening of December 1. Nixon then persuaded her to allow her case to be used to challenge the city's bus segregation policy. That evening, Nixon conferred with Alabama State College professor Jo Ann Robinson about Parks' case. Nixon also consulted African American attorney Fred Gray. Together, they agreed that a long-term legal challenge of bus segregation should be underscored by a one-day boycott of the bus system. Nixon and Robinson went about setting the boycott into motion that evening. Nixon spent the late evening drawing up a list and talking to prominent black leaders from Montgomery for support.

Four days later, Parks was tried on charges of disorderly conduct and violating a local ordinance. The trial lasted 30 minutes. Parks was found guilty and fined $10, plus $4 in court costs.[4] Parks appealed her conviction and formally challenged the legality of racial segregation. In a 1992 interview with National Public Radio's Lynn Neary, Parks recalled:

"I did not want to be mistreated, I did not want to be deprived of a seat that I had paid for. It was just time… there was opportunity for me to take a stand to express the way I felt about being treated in that manner. I had not planned to get arrested. I had plenty to do without having to end up in jail. But when I had to face that decision, I didn't hesitate to do so because I felt that we had endured that too long. The more we gave in, the more we complied with that kind of treatment, the more oppressive it became."

Montgomery bus boycott

On Monday, December 5, 1955, a group of 16 to 18 people gathered at the Mt. Zion AME Zion Church to discuss boycott strategies. The group agreed that a new organization was needed to lead the boycott effort if it were to continue. Rev. Ralph David Abernathy suggested the name "Montgomery Improvement Association" (MIA). The name was adopted, and the MIA was formed. Its members elected as their president a relative newcomer to Montgomery, a young and mostly unknown minister of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

That Monday night, 50 leaders of the African American community gathered to discuss the proper actions to be taken in response to Parks' arrest. E.D. Nixon said, "My God, look what segregation has put in my hands!" Parks was the ideal plaintiff for a test case against city and state segregation laws. While the 15-year-old Claudette Colvin, unwed and pregnant, had been deemed unacceptable to be the center of a civil rights mobilization, King stated; "Mrs. Parks, on the other hand, was regarded as one of the finest citizens of Montgomery; not one of the finest Negro citizens, but one of the finest citizens of Montgomery." Parks was securely married and employed, possessed a quiet and dignified demeanor, and was politically savvy.

The connection between Rosa Parks’ arrest and the boycott was not instantaneous. This was a planned resistance, not a spontaneous emotional response. The boycott had been planned and organized throughout 1955. It mobilized so quickly because of such planning. In the months preceding Parks’ arrest, three others had been arrested for refusing to give up their seats. Because of Parks’ civil rights leadership in Montgomery she was trusted not to cave in under the pressure everyone knew she would be exposed to, including threats on her life.

The night of Friday, December 2, 1955, Jo Ann Robinson of the Women's Political Council (WPC) mimeographed over 35,000 handbills announcing a bus boycott. The WPC was the first group to officially endorse the boycott.

On Sunday, December 4, 1955, plans for the Montgomery Bus Boycott were announced at black churches in the area, and a front-page article in The Montgomery Advertiser helped spread the word. At a church rally that night, attendees unanimously agreed to continue the boycott until they were treated with the level of courtesy they expected, until black drivers were hired, and until seating in the middle of the bus was handled on a first-come basis.

The day of Parks' trial, Monday, December 5, 1955, the WPC distributed the 35,000 leaflets. The handbill read, "We are…asking every Negro to stay off the buses Monday in protest of the arrest and trial…. You can afford to stay out of school for one day. If you work, take a cab, or walk. But please, children and grown-ups, don't ride the bus at all on Monday. Please stay off the buses Monday."[5]

It rained that day, but the black community persevered in their boycott. Some rode in carpools, while others traveled in black-operated cabs that charged the same fare as the bus, 10 cents. Most of the remainder of the 40,000 black commuters walked, some as far as twenty miles. In the end, the boycott lasted for 381 days. Dozens of public buses stood idle for months, severely damaging the bus transit company's finances, until the law requiring segregation on public buses was lifted.

Some segregationists retaliated with terrorism. Black churches were burned or dynamited. Martin Luther King's home was bombed in the early morning hours of January 30, 1956, and E.D. Nixon's home was also attacked. However, the black community's bus boycott marked one of the largest and most successful mass movements against racial segregation. It sparked many other protests, and it catapulted King to the forefront of the Civil Rights Movement.

Through her role in sparking the boycott, Rosa Parks played an important part in internationalizing the awareness of the plight of African Americans and the civil rights struggle. King wrote in his 1958 book Stride Toward Freedom that Parks' arrest was the precipitating factor, rather than the cause, of the protest:

"The cause lay deep in the record of similar injustices…. Actually, no one can understand the action of Mrs. Parks unless he realizes that eventually the cup of endurance runs over, and the human personality cries out, 'I can take it no longer.'"

The Montgomery bus boycott was also the inspiration for the bus boycott in the township of Alexandria in South Africa which was one of the key events in the radicalization of the black majority of that country under the leadership of the African National Congress.

The legal end to segregation

Immediately after the initiation of the bus boycott, legal strategists began to discuss the need for a federal lawsuit to challenge city and state bus segregation laws, and approximately two months after the boycott began, they reconsidered Claudette Colvin's case. Attorneys Fred Gray, E.D. Nixon and Clifford Durr searched for the ideal case law to challenge the constitutional legitimacy of city and state bus segregation laws. Parks' case was not used as the basis for the federal lawsuit because, as a criminal case, it would have had to make its way through the state criminal appeals process before a federal appeal could have been filed. City and state officials could have delayed a final rendering for years. Furthermore, attorney Durr believed it possible that the outcome would merely have been the vacating of Parks' conviction, with no changes in segregation laws. [6]

Gray researched for a better lawsuit, consulting with NAACP legal counsels Robert Carter and Thurgood Marshall, who would later become U.S. solicitor general and a U.S. Supreme Court justice. Gray approached Aurelia Browder, Susie McDonald, Claudette Colvin and Mary Louise Smith, all women who had had disputes involving the Montgomery bus system the previous year. They all agreed to become plaintiffs in a civil action law suit. Browder was a Montgomery housewife, Gayle the mayor of Montgomery. February 1, 1956, the case of Browder v. Gayle was filed in U.S. District Court by Fred Gray. It was Browder v. Gayle that brought segregation to an end on public buses. [7]

June 19, 1956, the U.S. District Court's three-judge panel ruled that Section 301 (31a, 31b and 31c) of Title 48, Code of Alabama, 1940, as amended, and Sections 10 and 11 of Chapter 6 of the Code of the City of Montgomery, 1952, "deny and deprive plaintiffs and other Negro citizens similarly situated of the equal protection of the laws and due process of law secured by the Fourteenth Amendment" (Browder v. Gayle, 1956). The court essentially decided that the precedent of Brown v. Board of Education (1954) could be applied to Browder v. Gayle. November 13, 1956, the United States Supreme Court outlawed racial segregation on buses, deeming it unconstitutional. The court order arrived in Montgomery, Alabama, December 20, 1956, and the bus boycott ended the next day. However, more violence erupted following the court order, as snipers fired into buses and into King's home, and terrorists threw bombs into churches and into the homes of many church ministers. [8]

Later years

After her arrest, Rosa Parks became an icon of the Civil Rights Movement, but suffered hardships as a result. She lost her job, and her husband quit his job after his boss forbade him from talking about his wife or the legal case. Parks traveled and spoke extensively. In 1957, Raymond and Rosa Parks left Montgomery for Hampton, Virginia—mostly because she was unable to find work, but also because of disagreements with King and other leaders of Montgomery's struggling civil rights movement. Later that year, at the urging of her younger brother Sylvester Parks, she, her husband Raymond, and her mother Leona McCauley, moved to Detroit, Michigan.

Parks worked as a seamstress until 1965, when African-American U.S. Representative John Conyers D-Michigan hired her as a secretary and receptionist for his congressional office in Detroit. She held this position until she retired in 1988. In a telephone interview with CNN on October 24 2005, Conyers recalled, "You treated her with deference because she was so quiet, so serene—just a very special person…. There is only one Rosa Parks." Later in life, Parks also served as a member of the Board of Advocates of the Planned Parenthood Federation of America.

Rosa Parks and Elaine Eason Steele co-founded the Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute for Self Development in February 1987, in honor of Rosa's husband, who died from cancer in 1977. The institute runs the "Pathways to Freedom" bus tours, which introduce young people to important civil rights and Underground Railroad sites throughout the country.

In 1992, Parks published Rosa Parks: My Story, an autobiography aimed at younger readers which details her life leading up to her decision not to give up her seat. In it she said:

“I have spent over half my life teaching love and brotherhood, and I feel that it is better to continue to try to teach or live equality and love than it would be to have hatred or prejudice. Everyone living together in peace and harmony and love - that’s the goal that we seek, and I think that the more people there are who reach that state of mind, the better we will all be.”

In 1995, she published her memoirs, titled Quiet Strength, which focuses on the role that her faith had played in her life.

Death and funeral

Rosa Parks resided in Detroit until she died at the age of 92 on October 24, 2005 in her apartment on the east side of the city. She had been diagnosed with progressive dementia in 2004.

City officials in Montgomery and Detroit announced on October 27 that the front seats of their city buses would be reserved with black ribbons in honor of Parks until her funeral. Parks' coffin was flown to Montgomery, Alabama and taken in a horse-drawn hearse to the St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal (AME) church, where she lay in repose at the altar, dressed in the uniform of a church deaconess, on October 29. A memorial service was held there the following morning at which Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice stated that if it were not for Rosa Parks, she would probably have never become the Secretary of State.

In the evening the casket was transported to Washington, D.C. and taken aboard a bus similar to the one in which she made her protest, to lay in state in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda, making her the first woman and second African American ever to receive this honor. An estimated 50,000 people viewed the casket there, with the event being broadcast on television. This was followed by another memorial service at St. Paul AME church in Washington on the afternoon of October 31. For two days, she lay in repose at the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History in Detroit, Michigan.

Parks' funeral service, seven hours long, was held on Wednesday, November 2, at the Greater Grace Temple Church. After the funeral service, an honor guard from the Michigan National Guard laid the U.S. flag over the casket and carried it to a horse-drawn hearse, which carried it to the cemetery. Thousands of people turned out to view the procession, applauding and releasing white balloons. Mrs. Parks was interred between her husband and mother at Detroit's Woodlawn Cemetery in the chapel's mausoleum. The chapel was renamed the Rosa L. Parks Freedom Chapel soon after her death. [9]

Awards and honors

Rosa Parks received most of her national accolades very late in life, receiving relatively few awards and honors until many decades after the Montgomery Bus Boycott. In 1979, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People awarded Parks the Spingarn Medal, its highest honor, and she received the Martin Luther King Sr. Award the next year. She was inducted into the Michigan Women's Hall of Fame in 1983 for her achievements in civil rights. In 1990, she was called to be part of the group welcoming Nelson Mandela, who had just been released from his imprisonment in South Africa. Upon spotting her in the reception line, Mandela called out her name and, hugging her, said, "You sustained me while I was in prison all those years." [10]

Parks received the Rosa Parks Peace Prize in 1994 in Stockholm, Sweden. On September 9, 1996, President Bill Clinton presented Parks with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest honor given by the U.S. executive branch. In 1998, she became the first recipient of the International Freedom Conductor Award given by the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center. The following year, Parks was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest award given by the U.S. legislative branch and also received the Detroit-Windsor International Freedom Festival Freedom Award. Mrs. Parks was a guest of President Bill Clinton during his 1999 State of the Union Address. Also that year, Time magazine named Parks one of the 20 most influential and iconic figures of the twentieth century.[11] In 2000, her home state awarded her the Alabama Academy of Honor, as well as the first Governor's Medal of Honor for Extraordinary Courage. She was also awarded two dozen honorary doctorates from universities worldwide, and was made an honorary member of the Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority.

The Rosa Parks Library and Museum on the campus of Troy University in Montgomery, Alabama, was dedicated to her on December 1, 2000. It is located on the corner where Parks boarded the famed bus. The documentary "Mighty Times: The Legacy of Rosa Parks" received a 2002 nomination for Academy Award for Documentary Short Subject. She also collaborated that year in a TV movie of her life starring Angela Bassett.

The United States Senate passed a resolution on October 27, 2005 to honor Parks by allowing her body to lie in state in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda. On October 30, President George W. Bush issued a Proclamation ordering that all flags on U.S. public areas both within the country and abroad be flown at half-staff on the day of Parks' funeral.

Metro Transit in King County, Washington placed stickers dedicating the first forward-facing seat of all its buses in Parks' memory shortly after her death, and the American Public Transportation Association declared December 1, 2005, the 50th anniversary of her arrest, to be a "National Transit Tribute to Rosa Parks Day." [12] On that anniversary, President George W. Bush signed H. R. 4145, directing that a statue of Parks be placed in the United States Capitol's National Statuary Hall. In signing the resolution directing the Joint Commission on the Library to do so, the President stated:

"By placing her statue in the heart of the nation's Capitol, we commemorate her work for a more perfect union, and we commit ourselves to continue to struggle for justice for every American." [13]

On February 5, 2006, at Super Bowl XL, played at Detroit's Ford Field, the late Coretta Scott King and Parks, who had been a long-time resident of "The Motor City," were remembered and honored by a moment of silence. It was noted that the honor was to show respect for two women who had "helped make the nation as a whole great."

Notes

- ↑ Rosa Parks Gale Cengage Learning, Contemporary Black Biography, Vol. 35. (Reproduced in Biography Resource Center. Thomson Gale.) Retrieved January 21, 2008.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Herbert Kohl, She Would Not Be Moved: How we tell the story of Rosa Parks and the Montgomery bus boycott (New York: The New Press, 2005).

- ↑ The New York Times Company - About.com. Jackie Robinson Profile.

- ↑ Civil rights icon Rosa Parks dies at 92 CNN.com, October 25, 2005. Retrieved January 21, 2008.

- ↑ Rita Dove, Heroes and Icons: Rosa Parks The TIME 100: TIME Magazine, June 14, 1999. Retrieved January 21, 2008.

- ↑ They Changed the World: The Story of the Montgomery Bus Boycott Montgomery Advertiser, 2005. Retrieved January 21, 2008.

- ↑ Tim Walker, Browder v. Gayle: The Women Before Rosa Parks Tolerance.org, 2005. Retrieved January 21, 2008.

- ↑ E.R. Shipp, Rosa Parks, 92, Founding Symbol of Civil Rights Movement, Dies New York Times, October 25, 2005. Retrieved January 21, 2008.

- ↑ Parks to remain private in death Detroit News. November 3, 2005. Retrieved November 7, 2013.

- ↑ Tri-state Judge Says Rosa Parks' Work Goes On Scripps TV Station Group - WPCO News. October 25, 2005. Retrieved January 21, 2008.

- ↑ Rita Dove, Rosa Parks: Her simple act of protest galvanized America's civil rights revolution, TIME Magazine, June 14, 1999. Retrieved January 21, 2008.

- ↑ National Transit Tribute to Rosa Parks Day American Public Transportation Association.

- ↑ President Signs H.R. 4145 to Place Statue of Rosa Parks in U.S. Capitol The White House, December 2005. Retrieved January 21, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- CNN News. "Civil rights icon Rosa Parks dies at 92" by CNN.com. October 25 2005.

- Dove, Rita. "Heroes and Icons: Rosa Parks" TIME 100, June 14 1999. TIME.com.

- Hare, Ken. "The Story of the Montgomery Bus Boycott" Montgomery Advertiser, October 2005.

- John Safran's Musical Jamboree.

- Kohl, Herbert. She Would Not Be Moved: how we tell the story of Rosa Parks and the Montgomery bus boycott. New York: The New Press, 2005. ISBN 1595580204

- Parks, Rosa, with James Haskins. Rosa Parks, My Story. New York: Dial Books, 1992. ISBN 0803706731

- Parks, Rosa, with Gregory J. Reed. Quiet Strength. Zondervan, 1994. ISBN 978-0310501503

- Shipp, E.R. "Rosa Parks, 92, Founding Symbol of Civil Rights Movement, Dies" The New York Times, October 25 2005.

- Walker, Tim. "Browder v. Gayle: The Women Before Rosa Parks," Tolerance.org.

- New York Times Editorial. "Two decades later," New York Times (May 17, 1974): 38. ("Within a year of Brown, Rosa Parks, a tired seamstress in Montgomery, Alabama, was, like Homer Plessy sixty years earlier, arrested for her refusal to move to the back of the bus.")

External links

All links retrieved December 16, 2022.

- Academy of Achievement Profile

- Academy of Achievement Biography

- Academy of Achievement Interview

- Academy of Achievement Photo Gallery

- The Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute for Self Development

- Civil Rights Icon Rosa Parks Dies - National Public Radio

- Rose Parks Biography

- Rosa Parks: cadre of working-class movement that ended Jim Crow

- Rosa Parks Quotes

- Rosa and Raymond Parks Marriage Profile

- Rosa Parks, a pioneer of civil rights, died on October 24th, aged 92

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.