Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn that began in the United States. The timing of the Great Depression varied across nations; in most countries, it started in 1929 and lasted until the late 1930s. It was the longest, deepest, and most widespread economic depression of the twentieth century. In the twenty-first century, the Great Depression is commonly used as an example of how intensely the world's economy can decline.

The Great Depression started in the United States after a major fall in stock prices that began around September 4, 1929, and became worldwide news with the stock market crash of October 29, 1929, (known as "Black Tuesday"). This crisis marked the start of a prolonged period of economic hardship characterized by high unemployment rates and widespread business failures. Cities around the world were hit hard, especially those dependent on heavy industry. Construction was virtually halted in many countries. Farming communities and rural areas suffered as crop prices fell.

The Great Depression had devastating effects in countries both rich and poor. Some economies started to recover by the mid-1930s. However for others, in particular the United States, the negative effects of the Great Depression lasted until the beginning of World War II. Even today there is no complete understanding of the causes and recovery from this economic disaster.

Overview

The Great Depression (1929–1939) was a severe global economic downturn that affected many countries across the world. It became evident after a sharp decline in stock prices in the United States, leading to a period of economic depression.[1] The economic contagion began around September 1929 and led to the Wall Street stock market crash of October (Black Tuesday). This crisis marked the start of a prolonged period of economic hardship characterized by high unemployment rates and widespread business failures. It was the longest, deepest, and most widespread depression of the twentieth century.

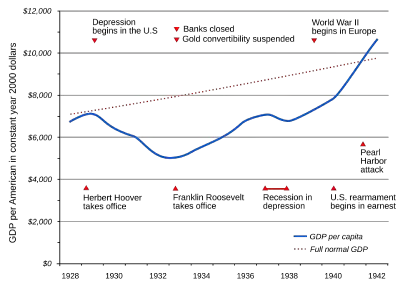

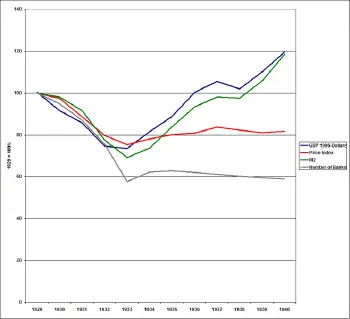

Between 1929 and 1932, worldwide gross domestic product (GDP) fell by an estimated 15 percent. Some economies started to recover by the mid-1930s. However, in many countries, the negative effects of the Great Depression lasted until the beginning of World War II.[1]

The Great Depression had devastating effects in countries both rich and poor. Personal income, tax revenue, profits, and prices dropped, while international trade plunged by more than 50 percent. Unemployment in the U.S. rose to 25 percent and in some countries rose as high as 33 percent.[2]

Cities around the world were hit hard, especially those dependent on heavy industry. Construction was virtually halted in many countries. Farming communities and rural areas suffered as crop prices fell dramatically. Facing plummeting demand with few alternative sources of jobs, areas dependent on primary sector industries such as mining and logging suffered the most.[3]

Economic historians usually consider the catalyst of the Great Depression to be the devastating Wall Street Crash. However, some dispute this, seeing the crash less as a cause of the Depression and more a symptom of the rising nervousness of investors, partly due to gradual price declines caused by falling sales of consumer goods (as a result of overproduction because of new production techniques, falling exports, and income inequality, among other factors) that had already been underway as part of a gradual depression.[2]

After the Wall Street Crash of 1929, where the Dow Jones Industrial Average dropped from 381 to 198 over the course of two months, optimism persisted for some time. The stock market rose in early 1930, with the Dow returning to 294 (pre-depression levels) in April 1930, before steadily declining for years, to a low of 41 in 1932.[4]

At the beginning, governments and businesses spent more in the first half of 1930 than in the corresponding period of the previous year. On the other hand, consumers, many of whom suffered severe losses in the stock market the previous year, cut expenditures by 10 percent. In addition, beginning in the mid-1930s, a severe drought ravaged the agricultural heartland of the U.S.[5]

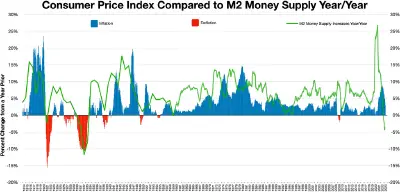

Interest rates dropped to low levels by mid-1930, but expected deflation and the continuing reluctance of people to borrow meant that consumer spending and investment remained low. By May 1930, automobile sales declined to below the levels of 1928. Prices, in general, began to decline, although wages held steady in 1930. Then a deflationary spiral started in 1931. Farmers faced a worse outlook; declining crop prices and a Great Plains drought crippled their economic outlook. At its peak, the Great Depression saw nearly 10 percent of all Great Plains farms change hands despite federal assistance.[6]

Frantic attempts by individual countries to shore up their economies through protectionist policies – such as the 1930 U.S. Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act and retaliatory tariffs in other countries – exacerbated the collapse in global trade, contributing to the depression. By 1933, the economic decline pushed world trade to one third of its level compared to four years earlier.[7]

Terminology

The term "The Great Depression" is most frequently attributed to British economist Lionel Robbins, whose 1934 book The Great Depression is credited with formalizing the phrase,[8] though Herbert Hoover is widely credited with popularizing the term, informally referring to the downturn as a "depression," with such uses as "Economic depression cannot be cured by legislative action or executive pronouncement" (December 1930, Message to Congress), and "I need not recount to you that the world is passing through a great depression" (1931).[9]

Financial crises were traditionally referred to as "panics," up to the early twentieth century, such as the major Panic of 1907, and the minor Panic of 1910–1911. The 1929 crisis was called "The Crash," and the term "panic" has since fallen out of use.

The term "depression" to refer to an economic downturn dates to the nineteenth century, when it was used by varied Americans and British politicians and economists. The first major American economic crisis, the Panic of 1819, was described by then-president James Monroe as "a depression," and the economic crisis in 1920–1921, was referred to as a "depression" by then-president Calvin Coolidge. In 1874, during the Panic of 1873, Ulysses S. Grant expressed his concern over “the depression in the industries and prosperity of our people.”[10] Rutherford B. Hayes similarly remarked during his inaugural address in 1877, that “the depression in all our varied commercial and manufacturing interests throughout the country, which began in September, 1873, still continues.”[11]

Course

| United States | United Kingdom | France | Germany | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industrial production | −46% | −23% | −24% | −41% |

| Wholesale prices | −32% | −33% | −34% | −29% |

| Foreign trade | −70% | −60% | −54% | −61% |

| Unemployment | +607% | +129% | +214% | +232% |

Origins

The origins of the Great Depression are examined in the context of the United States economy, which is where it originated before spreading around the world. In the aftermath of World War I, the Roaring Twenties had brought considerable wealth to the United States and Western Europe.[13] The year 1929 dawned with considerable progress in the American economy. A small stock crash occurred on March 25 1929, but was stabilized. Despite signs of economic trouble, the market continued to improve through September. Stock prices began to slump in September, and were volatile at the end of September. A large sell-off of stocks began in mid-October. Finally, on October 24, Black Thursday, the American stock market crashed 11 percent at the opening bell. Actions to stabilize the market failed, and on October 28, Black Monday, the market crashed another 12 percent. The panic peaked the next day on Black Tuesday, when the market saw another 11 percent drop.[14]

The market recovered 12 percent on Wednesday, but the damage had been done. Though the market recovered from November 14 until April 17, 1930, it entered a prolonged slump. From April 17, 1930 until July 8, 1932 (the lowest point), the market continued to lose 89 percent of its value. In March, 1933, although the Dow made a large gain, stocks were still trading at 87 percent of value. [14]

Despite the crash, the worst of the crisis did not reverberate around the world until after 1929. The crisis hit panic levels again in December 1930, with a bank run on the privately run Bank of United States. Unable to pay out to all of its creditors, the bank failed. Among the 608 American banks that closed in November and December 1930, the Bank of United States accounted for a third of the total $550 million deposits lost and, with its closure, bank failures reached a critical mass.[15]

The Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act

The Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act was passed in the United States on June 17, 1930, having been proposed the year prior. Sponsored by Senator Reed Smoot and Representative Willis C. Hawley, the act implemented protectionist trade policies in the United States, raising US tariffs on over 20,000 imported goods.

The sharp decline in international trade after 1930 has been cited as a factor that worsened the depression, especially for countries significantly dependent on foreign trade. The average ad valorem (value based) rate of duties on dutiable imports for 1921–1925 was 25.9 percent but under the new tariff it jumped to 50 percent during 1931–1935. In dollar terms, American exports declined over the next four years from about $5.2 billion in 1929 to $1.7 billion in 1933; so, not only did the physical volume of exports fall, but also the prices fell by about 1⁄3 as written.

Governments around the world took various steps into spending less money on foreign goods such as imposing tariffs, import quotas, and exchange controls. These restrictions triggered much tension among countries that had large amounts of bilateral trade, causing major export-import reductions during the depression. Not all governments enforced the same measures of protectionism. Some countries raised tariffs drastically and enforced severe restrictions on foreign exchange transactions, while other countries reduced trade and exchange restrictions only marginally:

- "Countries that remained on the gold standard, keeping currencies fixed, were more likely to restrict foreign trade." These countries "resorted to protectionist policies to strengthen the balance of payments and limit gold losses." They hoped that these restrictions and depletions would hold the economic decline.[16]

- Countries that abandoned the gold standard allowed their currencies to depreciate which caused their balance of payments to strengthen. It also freed up monetary policy so that central banks could lower interest rates and act as lenders of last resort. They possessed the best policy instruments to fight the Depression and did not need protectionism.[16]

- "The length and depth of a country's economic downturn and the timing and vigor of its recovery are related to how long it remained on the gold standard. Countries abandoning the gold standard relatively early experienced relatively mild recessions and early recoveries. In contrast, countries remaining on the gold standard experienced prolonged slumps."[16]

Gold standard

The gold standard was the primary transmission mechanism of the Great Depression.

Some economic studies have indicated that the rigidities of the gold standard not only spread the downturn worldwide, but also suspended gold convertibility (devaluing the currency in gold terms) that did the most to make recovery possible.[17]

Every major currency left the gold standard during the Great Depression. The UK was the first to do so. Facing speculative attacks on the pound and depleting gold reserves, in September 1931 the Bank of England ceased exchanging pound notes for gold and the pound was floated on foreign exchange markets. Japan and the Scandinavian countries followed in 1931. Other countries, such as Italy and the United States, remained on the gold standard into 1932 or 1933, while a few countries in the so-called "gold bloc," led by France and including Poland, Belgium, and Switzerland, stayed on the standard until 1935–1936.

According to later analysis, the earliness with which a country left the gold standard reliably predicted its economic recovery. For example, The UK and Scandinavia, which left the gold standard in 1931, recovered much earlier than France and Belgium, which remained on gold much longer. Countries such as China, which had a silver standard, almost avoided the depression entirely. This partly explains why the experience and length of the depression differed between regions and states around the world.

Banking crisis

The financial crisis escalated out of control in mid-1931, starting with the collapse of the Credit Anstalt in Vienna in May.[18] Soon, industrial failures began, a major bank closed in July, and a two-day holiday for all German banks was declared. Business failures spread to Romania and Hungary. The crisis continued to get worse in Germany, bringing political upheaval that finally led to the Adolf Hitler's rise to power in January 1933.

The world financial crisis then began to overwhelm Britain. The financial crisis caused a major political crisis in Britain in August 1931, and in the election the Labour Party was virtually destroyed, leaving Ramsay MacDonald as prime minister for a largely Conservative coalition.[19]

Recovery

In most countries of the world, recovery from the Great Depression began in 1933. In the U.S., recovery began in early 1933, but the U.S. did not return to 1929 GNP for over a decade and still had an unemployment rate of about 15 percent in 1940, albeit down from the high of 25 percent in 1933. There is no consensus among economists regarding the motive force for the U.S. economic expansion that continued through most of the Roosevelt years (and the 1937 recession that interrupted it).

World War II

The common view among economic historians is that the Great Depression ended with the advent of World War II. Many economists believe that government spending on the war caused or at least accelerated recovery from the Great Depression, though some consider that it did not play a very large role in the recovery, though it did help in reducing unemployment.

The rearmament policies leading up to World War II helped stimulate the economies of Europe in 1937–1939. By 1937, unemployment in Britain had fallen to 1.5 million. The mobilization of manpower following the outbreak of war in 1939 ended unemployment.

The American mobilization for World War II at the end of 1941 moved millions of people out of the civilian labor force and into the war and jobs in military-related industries. This finally eliminated the last effects from the Great Depression and brought the U.S. unemployment rate down below 10 percent.[20]

Causes

Modern mainstream economists see the reasons in

- A money supply reduction (Monetarists) and therefore a banking crisis, reduction of credit, and bankruptcies.

- Insufficient demand from the private sector and insufficient fiscal spending (Keynesians).

- Passage of the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act exacerbated what otherwise might have been a more "standard" recession (both Monetarists and Keynesians).[21]

The two classic competing economic theories of the Great Depression are the Keynesian (demand-driven) and the Monetarist explanation. There are also various heterodox theories that downplay or reject the explanations of the Keynesians and Monetarists.

Economists and economic historians are almost evenly split as to whether the traditional monetary explanation that monetary forces were the primary cause of the Great Depression is right, or the traditional Keynesian explanation that a fall in autonomous spending, particularly investment, is the primary explanation for the onset of the Great Depression.[21] Today there is also significant academic support for the debt deflation theory and the expectations hypothesis that, building on the monetary explanation of Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz, add non-monetary explanations.

There is a consensus that the Federal Reserve System, which was created in 1913, should have cut short the process of monetary deflation and banking collapse, by expanding the money supply and acting as lender of last resort. If they had done this, the economic downturn would have been far less severe and much shorter.[21]

Monetarist view

The monetarist explanation was given by American economists Milton Friedman and Anna J. Schwartz.[22] They argued that the Great Depression was caused by the banking crisis that caused one-third of all banks to vanish, a reduction of bank shareholder wealth, and more importantly monetary contraction of 35 percent, which they called "The Great Contraction." This caused a price drop of 33 percent (deflation).[23]

The Federal Reserve allowed some large public bank failures – particularly that of the New York Bank of United States – which produced panic and widespread runs on local banks, and the Federal Reserve sat idly by while banks collapsed. Friedman and Schwartz argued that, if the Fed had provided emergency lending to these key banks, or simply bought government bonds on the open market to provide liquidity and increase the quantity of money after the key banks fell, all the rest of the banks would not have fallen after the large ones did, and the money supply would not have fallen as far and as fast as it did.

By not lowering interest rates, by not increasing the monetary base, and by not injecting liquidity into the banking system to prevent it from crumbling, the Federal Reserve passively watched the transformation of a normal recession into the Great Depression. Friedman and Schwartz argued that the downward turn in the economy, starting with the stock market crash, would merely have been an ordinary recession if the Federal Reserve had taken aggressive action.[24] This view was endorsed in 2002 by Federal Reserve Governor Ben Bernanke in a speech honoring Friedman and Schwartz with this statement:

Let me end my talk by abusing slightly my status as an official representative of the Federal Reserve. I would like to say to Milton and Anna: Regarding the Great Depression, you're right. We did it. We're very sorry. But thanks to you, we won't do it again.[25]

One reason why the Federal Reserve did not act to limit the decline of the money supply was the gold standard. At that time, the amount of credit the Federal Reserve could issue was limited by the Federal Reserve Act, which required 40 percent gold backing of Federal Reserve Notes issued. By the late 1920s, the Federal Reserve had almost hit the limit of allowable credit that could be backed by the gold in its possession. This credit was in the form of Federal Reserve demand notes.[26] During the bank panics, a portion of those demand notes was redeemed for Federal Reserve gold. Since the Federal Reserve had hit its limit on allowable credit, any reduction in gold in its vaults had to be accompanied by a greater reduction in credit.

Keynesian view

British economist John Maynard Keynes argued in The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money that lower aggregate expenditures in the economy contributed to a massive decline in income and to employment that was well below the average. In such a situation, the economy reached equilibrium at low levels of economic activity and high unemployment.

Keynes' basic idea was simple: to keep people fully employed, governments have to run deficits when the economy is slowing, as the private sector would not invest enough to keep production at the normal level and bring the economy out of recession. Keynesian economists called on governments during times of economic crisis to pick up the slack by increasing government spending or cutting taxes.

As the Depression wore on, Franklin D. Roosevelt tried public works, farm subsidies, and other devices to restart the U.S. economy, but never completely gave up trying to balance the budget. According to the Keynesians, this improved the economy, but Roosevelt never spent enough to bring the economy out of recession until the start of World War II.[27]

Debt deflation

Irving Fisher argued that the predominant factor leading to the Great Depression was a vicious circle of deflation and growing over-indebtedness.[28] He outlined nine factors interacting with one another under conditions of debt and deflation to create the mechanics of boom to bust. The chain of events proceeded as follows:

- Debt liquidation and distress selling

- Contraction of the money supply as bank loans are paid off

- A fall in the level of asset prices

- A still greater fall in the net worth of businesses, precipitating bankruptcies

- A fall in profits

- A reduction in output, in trade and in employment

- Pessimism and loss of confidence

- Hoarding of money

- A fall in nominal interest rates and a rise in deflation adjusted interest rates[28]

During the Crash of 1929 preceding the Great Depression, margin requirements were only 10 percent. In other words, brokerage firms would lend $9 for every $1 an investor had deposited. When the market fell, brokers called in these loans, which could not be paid back. Banks began to fail as debtors defaulted on debt and depositors attempted to withdraw their deposits en masse, triggering multiple bank runs. Government guarantees and Federal Reserve banking regulations to prevent such panics were ineffective or not used. Bank failures led to the loss of billions of dollars in assets. After the panic of 1929 and during the first 10 months of 1930, 744 U.S. banks failed. (In all, 9,000 banks failed during the 1930s.) By April 1933, around $7 billion in deposits had been frozen in failed banks or those left unlicensed after the March Bank Holiday.[22] Bank failures snowballed as desperate bankers called in loans that borrowers did not have time or money to repay. With future profits looking poor, capital investment and construction slowed or completely ceased. In the face of bad loans and worsening future prospects, the surviving banks became even more conservative in their lending.[29] Banks built up their capital reserves and made fewer loans, which intensified deflationary pressures. A vicious cycle developed and the downward spiral accelerated.

The liquidation of debt could not keep up with the fall of prices that it caused. The mass effect of the stampede to liquidate increased the value of each dollar owed, relative to the value of declining asset holdings. The very effort of individuals to lessen their burden of debt effectively increased it. Paradoxically, the more the debtors paid, the more they owed.[28] This self-aggravating process turned a 1930 recession into a 1933 great depression.

Fisher's debt-deflation theory initially lacked mainstream influence because of the counter-argument that debt-deflation represented no more than a redistribution from one group (debtors) to another (creditors). Pure re-distributions should have no significant macroeconomic effects.

Building on both the monetary hypothesis of Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz and the debt deflation hypothesis of Irving Fisher, Ben Bernanke developed an alternative way in which the financial crisis affected output. He builds on Fisher's argument that dramatic declines in the price level and nominal incomes lead to increasing real debt burdens, which in turn leads to debtor insolvency and consequently lowers aggregate demand; a further price level decline would then result in a debt deflationary spiral. According to Bernanke, a small decline in the price level simply reallocates wealth from debtors to creditors without doing damage to the economy. But when the deflation is severe, falling asset prices along with debtor bankruptcies lead to a decline in the nominal value of assets on bank balance sheets. Banks will react by tightening their credit conditions, which in turn leads to a credit crunch that seriously harms the economy. A credit crunch lowers investment and consumption, which results in declining aggregate demand and additionally contributes to the deflationary spiral.[23]

Expectations hypothesis

Since economic mainstream turned to the new neoclassical synthesis, expectations are a central element of macroeconomic models. According to Peter Temin, Barry Wigmore, Gauti B. Eggertsson, and Christina Romer, the key to recovery and to ending the Great Depression was brought about by a successful management of public expectations. Their thesis is based on the observation that after years of deflation and a very severe recession, important economic indicators turned positive in March 1933 when Franklin D. Roosevelt took office. Consumer prices turned from deflation to a mild inflation, industrial production bottomed out in March 1933, and investment doubled in 1933 with a turnaround in March 1933. There were no monetary forces to explain that turnaround. Money supply was still falling and short-term interest rates remained close to zero. Before March 1933, people expected further deflation and a recession so that even interest rates at zero did not stimulate investment. But when Roosevelt announced major regime changes, people began to expect inflation and an economic expansion. With these positive expectations, interest rates at zero began to stimulate investment just as they were expected to do. Roosevelt's fiscal and monetary policy regime change helped make his policy objectives credible. The expectation of higher future income and higher future inflation stimulated demand and investment.

The analysis suggests that the elimination of the policy dogmas of the gold standard, a balanced budget in times of crisis and small government led endogenously to a large shift in expectation that accounts for about 70–80% of the recovery of output and prices from 1933 to 1937. If the regime change had not happened and the Hoover policy had continued, the economy would have continued its free fall in 1933, and output would have been 30 percent lower in 1937 than in 1933.[30][31]

The recession of 1937–1938, which slowed down economic recovery from the Great Depression, is explained by fears of the population that the moderate tightening of the monetary and fiscal policy in 1937 were first steps to a restoration of the pre-1933 policy regime.[30]

Heterodox theories

Austrian School

Ludwig von Mises wrote in the 1930s:

Credit expansion cannot increase the supply of real goods. It merely brings about a rearrangement. It diverts capital investment away from the course prescribed by the state of economic wealth and market conditions. It causes production to pursue paths which it would not follow unless the economy were to acquire an increase in material goods. As a result, the upswing lacks a solid base. It is not real prosperity. It is illusory prosperity. It did not develop from an increase in economic wealth, i.e. the accumulation of savings made available for productive investment. Rather, it arose because the credit expansion created the illusion of such an increase. Sooner or later, it must become apparent that this economic situation is built on sand.[32]

Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek and American economist Murray Rothbard, prominent theorists in the Austrian School, expressed their understanding of the cause of the Great Depression. In their view, much like the Monetarists, the Federal Reserve shoulders much of the blame; however, unlike the Monetarists, they argue that the key cause of the Depression was the expansion of the money supply in the 1920s which led to an unsustainable credit-driven boom.[33]

In the Austrian view, it was this inflation of the money supply that led to an unsustainable boom in both asset prices (stocks and bonds) and capital goods. Therefore, by the time the Federal Reserve tightened in 1928 it was far too late to prevent an economic contraction. According to Rothbard, the government support for failed enterprises and efforts to keep wages above their market values actually prolonged the Depression.[33]

During the Depression (in 1932 and in 1934) Hayek had criticized both the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England for not taking a more contractionary stance.[34] However, unlike Rothbard, after 1970 Hayek believed that the Federal Reserve had further contributed to the problems of the Depression by permitting the money supply to shrink during the earliest years of the Depression.[35]

Inequality

Two economists of the 1920s, Waddill Catchings and William Trufant Foster, popularized a theory that influenced many policy makers, including Herbert Hoover, Henry A. Wallace, Paul Douglas, and Marriner Eccles.[36] It held the economy produced more than it consumed, because the consumers did not have enough income. Thus the unequal distribution of wealth throughout the 1920s caused the Great Depression.

According to this view, the root cause of the Great Depression was a global over-investment in heavy industry capacity compared to wages and earnings from independent businesses, such as farms. The proposed solution was for the government to pump money into the consumers' pockets. That is, it must redistribute purchasing power, maintaining the industrial base, and re-inflating prices and wages to force as much of the inflationary increase in purchasing power into consumer spending. The economy was overbuilt, and new factories were not needed. Foster and Catchings recommended[36] federal and state governments to start large construction projects, a program followed by Hoover and Roosevelt.

Marxist

Marxists generally argue that the Great Depression was the result of the inherent instability of the capitalist mode of production.[37] "The idea that capitalism caused the Great Depression was widely held among intellectuals and the general public for many decades."[38]

Common position

At the beginning of the Great Depression, most economists believed in Say's law and the equilibrating powers of the market, and failed to understand the severity of the Depression. Outright leave-it-alone liquidationism was a common position, and was universally held by Austrian School economists.[23] The liquidationist position held that a depression worked to liquidate failed businesses and investments that had been made obsolete by technological development – releasing factors of production (capital and labor) to be redeployed in other more productive sectors of the dynamic economy. They argued that even if self-adjustment of the economy caused mass bankruptcies, it was still the best course.[23]

An increasingly common view among economic historians is that the adherence of many Federal Reserve policymakers to the liquidationist position led to disastrous consequences. Unlike what liquidationists expected, a large proportion of the capital stock was not redeployed but vanished during the first years of the Great Depression. The recession caused a drop of net capital accumulation to pre-1924 levels by 1933.[39] Milton Friedman disagreed with leave-it-alone liquidationism, saying it did more harm than good:

I think the Austrian business-cycle theory has done the world a great deal of harm. If you go back to the 1930s, which is a key point, here you had the Austrians sitting in London, Hayek and Lionel Robbins, and saying you just have to let the bottom drop out of the world. You've just got to let it cure itself. You can't do anything about it. You will only make it worse. ... I think by encouraging that kind of do-nothing policy both in Britain and in the United States, they did harm.[40]

There is common consensus among economists today that the government and the central bank should work to keep the interconnected macroeconomic aggregates of gross domestic product and money supply on a stable growth path. When threatened by expectations of a depression, central banks should expand liquidity in the banking system and the government should cut taxes and accelerate spending in order to prevent a collapse in money supply and aggregate demand.[39]

Socio-economic effects

Household economics

Without a steady flow of family income, the work of maintaining a household, dealing with food, clothing, and medical care, became much harder. Birthrates fell everywhere, as children were postponed until families could financially support them. The average birthrate for 14 major countries fell 12 percent from 19.3 births per thousand population in 1930, to 17.0 in 1935.[41] In Canada, half of Roman Catholic women defied Church teachings and used contraception to postpone births.[42]

In France, very slow population growth continued to be a serious issue in the 1930s. Support for increasing welfare programs during the depression included a focus on women in the family. The Conseil Supérieur de la Natalité campaigned for provisions enacted in the Code de la Famille (1939) that increased state assistance to families with children and required employers to protect the jobs of fathers, even if they were immigrants.

Oral history provides evidence for how housewives in a modern industrial city handled shortages of money and resources. Often they updated strategies their mothers used when they were growing up in poor families. Cheap foods were used, such as soups, beans, and noodles. They purchased the cheapest cuts of meat, sometimes even horse meat. They sewed and patched clothing, traded with their neighbors for outgrown items, and made do with colder homes. New furniture and appliances were postponed until better days. Many women also worked outside the home, or took boarders, did laundry for trade or cash, and did sewing for neighbors in exchange for something they could offer. Extended families used mutual aid—extra food, spare rooms, repair-work, cash loans—to help cousins and in-laws.[42]

In rural and small-town areas, women expanded their operation of vegetable gardens to include as much food production as possible. In the United States, agricultural organizations sponsored programs to teach housewives how to optimize their gardens and to raise poultry for meat and eggs.[43] Rural women made dresses and other items for themselves and their families and homes from feed sacks.[44] In American cities, African American women quiltmakers enlarged their activities, promoted collaboration, and trained neophytes. Quilts were created for practical use from various inexpensive materials and increased social interaction for women and promoted camaraderie and personal fulfillment.[45]

In Japan, official government policy was deflationary and the opposite of Keynesian spending. Consequently, the government launched a campaign across the country to induce households to reduce their consumption, focusing attention on spending by housewives.[46]

In Germany, the government tried to reshape private household consumption under the Four-Year Plan of 1936 to achieve German economic self-sufficiency. The Nazi women's organizations, other propaganda agencies and the authorities all attempted to shape such consumption as economic self-sufficiency was needed to prepare for and to sustain the coming war. The organizations, propaganda agencies and authorities employed slogans that called up traditional values of thrift and healthy living. However, these efforts were only partly successful in changing the behavior of housewives.[47]

The majority of countries set up relief programs and most underwent some sort of political upheaval, pushing them to the right. Many of the countries in Europe and Latin America that were democracies saw them overthrown by some form of dictatorship or authoritarian rule, most famously in Germany in 1933. There too were severe impacts across the Middle East and North Africa, including economic decline which led to social unrest.[48]

Germany

The Great Depression hit Germany hard. The impact of the Wall Street Crash forced American banks to end the new loans that had been funding the repayments under the Dawes Plan and the Young Plan. The financial crisis escalated out of control in mid-1931, starting with the collapse of the Credit Anstalt in Vienna in May.[18] This put heavy pressure on Germany, which was already in political turmoil with the rise in violence of national socialist and communist movements, as well as with investor nervousness at harsh government financial policies, investors withdrew their short-term money from Germany as confidence spiraled downward. The Reichsbank lost 150 million marks in the first week of June, 540 million in the second, and 150 million in two days, June 19–20. Collapse was at hand. U.S. President Herbert Hoover called for a moratorium on payment of war reparations.

In 1932, 90 percent of German reparation payments were cancelled (in the 1950s, Germany repaid all its missed reparations debts). Widespread unemployment reached 25 percent as every sector was hurt. The government did not increase government spending to deal with Germany's growing crisis, as they were afraid that a high-spending policy could lead to a return of the hyperinflation that had affected Germany in 1923.

The German political landscape was dramatically altered, leading to Adolf Hitler's rise to power. Hitler followed an autarky economic policy, creating a network of client states and economic allies in central Europe and Latin America. By cutting wages and taking control of labor unions, plus public works spending, unemployment fell significantly by 1935. Large-scale military spending played a major role in the recovery.[49] The policies had the effect of driving up the cost of food imports and depleting foreign currency reserves, leading to economic impasse by 1936. Nazi Germany faced a choice of either reversing course or pressing ahead with rearmament and autarky. Hitler chose the latter route, which "could only be partially accomplished without territorial expansion" and therefore war.[50] The result was not only World War II, which impacted millions of lives, both solders and civilians, but also the Holocaust which involved systematic persecution and genocide of the Jews and others.

European African colonies

The sharp fall in commodity prices, and the steep decline in exports, hurt the economies of the European colonies in Africa and Asia.[51] The agricultural sector was especially hard hit. There was widespread unemployment and hardship among peasants, laborers, colonial auxiliaries, and artisans.[52] The budgets of colonial governments were cut, which forced the reduction in ongoing infrastructure projects, such as the building and upgrading of roads, ports, and communications as well as delaying the schedule for creating systems of higher education.

French West Africa launched an extensive program of educational reform in which "rural schools" designed to modernize agriculture would stem the flow of under-employed farm workers to cities where unemployment was high. Students were trained in traditional arts, crafts, and farming techniques and were then expected to return to their own villages and towns.[53]

Latin America

Before the 1929 crisis, links between the world economy and Latin American economies had been established through American and British investment in Latin American exports to the world. As a result, Latin Americans export industries felt the depression quickly. World prices for commodities such as wheat, coffee and copper plunged. Exports from all of Latin America to the U.S. fell in value from $1.2 billion in 1929 to $335 million in 1933, rising to $660 million in 1940.

Because of high levels of U.S. investment in Latin American economies, they were severely damaged by the Depression. Within the region, Chile, Bolivia, and Peru were particularly badly affected.[54]

On the other hand, the depression led the area governments to develop new local industries and expand consumption and production. Following the example of the New Deal, governments in the area approved regulations and created or improved welfare institutions that helped millions of new industrial workers to achieve a better standard of living.

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union was the only major socialist state in the world and had very little international trade. Its economy was not tied to the rest of the world and was mostly unaffected by the Great Depression.[55]

At the time of the Depression, the Soviet economy was growing steadily, fueled by intensive investment in heavy industry. The apparent economic success of the Soviet Union at a time when the capitalist world was in crisis led many Western intellectuals to view the Soviet system favorably:

As the Great Depression ground on and unemployment soared, intellectuals began unfavorably comparing their faltering capitalist economy to Russian Communism. Karl Marx had predicted that capitalism would fall under the weight of its own contradictions, and now with the economic crisis gripping the West, his predictions seem to be coming true. By contrast Russia seemed an emblematic modern nation, making the staggering leap from a feudal past to an industrial future with ease.[56]

The Great Depression caused mass immigration to the Soviet Union, mostly from Finland and Germany. Soviet Russia was at first happy to help these immigrants settle, because they believed they were victims of capitalism who had come to help the Soviet cause. However, when the Soviet Union entered the war in 1941, most of these Germans and Finns were arrested and sent to Siberia, while their Russian-born children were placed in orphanages.

United Kingdom

The World Depression broke at a time when the United Kingdom had still not fully recovered from the effects of the First World War more than a decade earlier. The financial crisis now caused a major political crisis in Britain in August 1931. With deficits mounting, the bankers demanded a balanced budget; the divided cabinet of Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald's Labour government agreed; it proposed to raise taxes, cut spending and most controversially, to cut unemployment benefits by 20 percent. The attack on welfare was totally unacceptable to the Labour movement. In the 1931 British election, the Labour Party was virtually destroyed, leaving MacDonald as prime minister for a largely Conservative coalition.[19]

The effects on the northern industrial areas of Britain were immediate and devastating, as demand for traditional industrial products collapsed. By the end of 1930 unemployment had more than doubled from 1 million to 2.5 million (20 percent of the insured workforce), and exports had fallen in value by 50 percent. In the less industrial Midlands and Southern England, the effects were short-lived and the later 1930s were a prosperous time. Growth in modern manufacture of electrical goods and a boom in the motor car industry was helped by a growing southern population and an expanding middle class. Agriculture also saw a boom during this period.[57]

United States

In June 1930, Congress approved the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act which raised tariffs on thousands of imported items. The intent of the Act was to encourage the purchase of American-made products by increasing the cost of imported goods, while raising revenue for the federal government and protecting farmers. Most countries that traded with the U.S. increased tariffs on American-made goods in retaliation, reducing international trade, and worsening the Depression. In 1931, Hoover urged bankers to set up the National Credit Corporation so that big banks could help failing banks survive. But bankers were reluctant to invest in failing banks, and the National Credit Corporation did almost nothing to address the problem.[58]

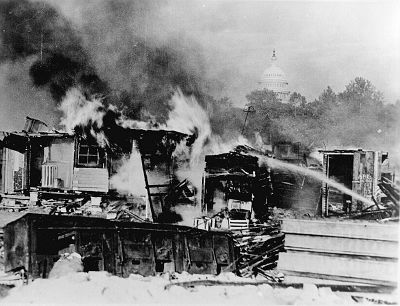

By 1932, unemployment had reached 23.6 percent, peaking in early 1933 at 25 percent. Drought persisted in the agricultural heartland, businesses and families defaulted on record numbers of loans, and more than 5,000 banks had failed. Hundreds of thousands of Americans found themselves homeless, and began congregating in shanty towns – dubbed "Hoovervilles" – that began to appear across the country. In response, President Hoover and Congress approved the Federal Home Loan Bank Act, to spur new home construction, and reduce foreclosures. The final attempt of the Hoover Administration to stimulate the economy was the passage of the Emergency Relief and Construction Act (ERA) which included funds for public works programs such as dams and the creation of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) in 1932. The Reconstruction Finance Corporation was a Federal agency with the authority to lend up to $2 billion to rescue banks and restore confidence in financial institutions. But $2 billion was not enough to save all the banks, and bank runs and bank failures continued.[58] Quarter by quarter the economy went downhill, as prices, profits and employment fell, leading to the political realignment in 1932 that brought to power Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

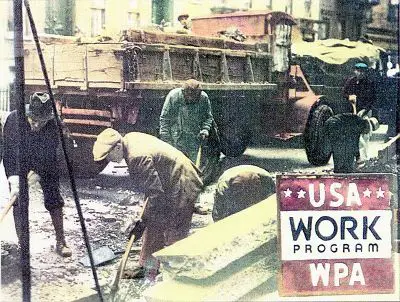

Shortly after President Franklin Delano Roosevelt was inaugurated in 1933, drought and erosion combined to cause the Dust Bowl, shifting hundreds of thousands of displaced persons off their farms in the Midwest. From his inauguration onward, Roosevelt argued that restructuring of the economy would be needed to prevent another depression or avoid prolonging the current one. New Deal programs sought to stimulate demand and provide work and relief for the impoverished through increased government spending and the institution of financial reforms.

During a "bank holiday" that lasted five days, the Emergency Banking Act was signed into law. It provided for a system of reopening sound banks under Treasury supervision, with federal loans available if needed. The Securities Act of 1933 comprehensively regulated the securities industry. This was followed by the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 which created the Securities and Exchange Commission. Although amended, key provisions of both Acts are still in force. Federal insurance of bank deposits was provided by the FDIC, and the Glass–Steagall Act.

The Agricultural Adjustment Act provided incentives to cut farm production in order to raise farming prices. The National Recovery Administration (NRA) made a number of sweeping changes to the American economy. It forced businesses to work with government to set price codes through the NRA to fight deflationary "cut-throat competition" by the setting of minimum prices and wages, labor standards, and competitive conditions in all industries. It encouraged unions that would raise wages, to increase the purchasing power of the working class. The NRA was deemed unconstitutional by the Supreme Court of the United States in 1935.

These reforms, together with several other relief and recovery measures, are called the First New Deal. Economic stimulus was attempted through a new alphabet soup of agencies set up in 1933 and 1934 and previously extant agencies such as the Reconstruction Finance Corporation. By 1935, the "Second New Deal" added Social Security (which was later considerably extended through the Fair Deal), a jobs program for the unemployed (the Works Progress Administration, WPA) and, through the National Labor Relations Board, a strong stimulus to the growth of labor unions.

In 1929, federal expenditures constituted only 3 percent of the GDP. The national debt as a proportion of GNP rose under Hoover from 20 percent to 40 percent. Between 1933 and 1939, federal expenditure tripled, and Roosevelt's critics charged that he was turning America into a socialist state.[59] The Great Depression was a main factor in the implementation of social democracy and planned economies in European countries after World War II.

Literature

The Great Depression has been the subject of much writing, as authors have sought to evaluate an era that caused both financial and emotional trauma. Perhaps the most noteworthy and famous novel written on the subject is The Grapes of Wrath, published in 1939 and written by John Steinbeck, who was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for the work, and in 1962 was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature.

| And the great owners, who must lose their land in an upheaval, the great owners with access to history, with eyes to read history and to know the great fact: when property accumulates in too few hands it is taken away. And that companion fact: when a majority of the people are hungry and cold they will take by force what they need. And the little screaming fact that sounds through all history: repression works only to strengthen and knit the repressed. —–John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath[60] |

The novel focuses on a poor family of sharecroppers who are forced from their home as drought, economic hardship, and changes in the agricultural industry occur during the Great Depression. Steinbeck's Of Mice and Men is another important novella about a journey during the Great Depression. Additionally, Harper Lee's To Kill a Mockingbird is set during the Great Depression, while Margaret Atwood's Booker prize-winning The Blind Assassin is likewise set in the Great Depression, centering on a privileged socialite's love affair with a Marxist revolutionary.

The era spurred the resurgence of social realism, practiced by many who started their writing careers on relief programs, especially the Federal Writers' Project in the U.S.[61]

A number of works for younger audiences are also set during the Great Depression, among them the Kit Kittredge series of American Girl books written by Valerie Tripp and illustrated by Walter Rane, released to tie in with the dolls and playsets sold by the company. The stories, which take place during the early to mid 1930s in Cincinnati, focus on the changes brought by the Depression to the titular character's family and how they dealt with it. A theatrical adaptation of the series entitled Kit Kittredge: An American Girl was later released in 2008 to positive reviews, as were a number of other movies that revealed life in the Depression era through the eyes of a child.[62] Similarly, Christmas After All, part of the Dear America series of books for older girls, take place in 1930s Indianapolis; while Kit Kittredge is told in a third-person viewpoint, Christmas After All is in the form of a fictional journal as told by the protagonist Minnie Swift as she recounts her experiences during the era, especially when her family takes in an orphan cousin from Texas.[63]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 John A. Garraty, The Great Depression (Anchor, 1987, ISBN 978-0385240857).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Robert H. Frank and Ben S. Bernanke, Principles of Macroeconomics (McGraw-Hill Education, 2012, ISBN 978-0077318505).

- ↑ Broadus Mitchell, Depression Decade: From New Era Through New Deal, 1929-1941 (Routledge, 2017).

- ↑ 1998/99 Prognosis Based Upon 1929 Market Autopsy Gold Eagle, June 6, 1998. Retrieved July 23, 2024.

- ↑ The Dust Bowl Drought National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved July 23, 2024.

- ↑ The Dust Bowl National Drought Mitigation Center. Retrieved July 23, 2024.

- ↑ Jeremy Adelman, Elizabeth Pollard, Clifford Rosenberg, and Robert Tignor, Worlds Together, Worlds Apart: A History of the World from the Beginnings of Humankind to the Present (W. W. Norton & Company, 2021, ISBN 978-0393532043).

- ↑ Lionel Robbins, The Great Depression (Routledge, 2009 (original 1934), ISBN 978-1412810081)

- ↑ William Manchester, The Glory and the Dream: A Narrative History of America, 1932–1972 (Little Brown & Co, 1974, ISBN 978-0316544962).

- ↑ Noah Mendel, When Did the Great Depression Receive Its Name? (And Who Named It?) History News Network. Retrieved July 25, 2024.

- ↑ Rutherford B. Hayes, Inaugural Address, March 5, 1877 The American Presidency Project. Retrieved July 25, 2024.

- ↑ Jerome Blum, Rondo Cameron, and Thomas G. Barnes, The European World: A History (2nd ed) (Little, Brown, 1970, ISBN 978-0316100274).

- ↑ George H. Soule, Prosperity Decade: From War to Depression: 1917–1929 (Routledge, 1977, ISBN 0873320980).

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Adrian Mastracci, The Great Crash of 1929, some key dates Financial Post (October 24, 2011). Retrieved July 25, 2024.

- ↑ Niall Ferguson, The Ascent of Money (Penguin Books, 2009, ISBN 978-0143116172).

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Barry Eichengreen and Douglas A. Irwin, The Slide to Protectionism in the Great Depression: Who Succumbed and Why? The Journal of Economic History 70(4) (December 2010): 871–897. Retrieved July 25, 2024.

- ↑ Barry Eichengreen, Golden Fetters: The Gold Standard and the Great Depression, 1919–1939 (Oxford University Press, 1992, ISBN 978-0195101133).

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 William Ashworth, A Short History of the International Economy Since 1850 (Hassell Street Press, 2021, ISBN 978-1013897023).

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Sean Glynn and John Oxborrow, Interwar Britain: A social and economic history (Allen & Unwin, 1976, ISBN 978-0049421417).

- ↑ U.S. History Primary Source Timeline: World War II Library of Congress. Retrieved July 25, 2024.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Robert Whaples, Where Is There Consensus Among American Economic Historians? The Results of a Survey on Forty Propositions The Journal of Economic History 55(1) (March, 1995): 139-154. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Milton Friedman and Anna Jacobson Schwartz, A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960 (Princeton University Press, 1971, ISBN 978-0691003542).

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 Randall E. Parker, Reflections on the Great Depression (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2002, ISBN 1840647450).

- ↑ Milton Friedman and Anna Jacobson Schwartz, The Great Contraction, 1929-1933 New Edition (Princeton University Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0691137940).

- ↑ Ben S. Bernanke, Remarks by Governor Ben S. Bernanke Conference to Honor Milton Friedman, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, November 8, 2002. Retrieved July 27, 2024.

- ↑ Frank Freidel, Franklin D. Roosevelt: Launching the New Deal (Little Brown & Co, 1973, ISBN 978-0316293037).

- ↑ Theodore Rosenof, Economics in the Long Run: New Deal Theorists and Their Legacies, 1933–1993 (University of North Carolina Press, 1997, ISBN 978-0807823156).

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Irving Fisher, The Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions (Martino Fine Books, 2011 (original 1933), ISBN 978-1614270102).

- ↑ Bill Ganzel, Bank Failures Wessels Living History Farm. Retrieved July 27, 2024.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Gauti B. Eggertsson, Great Expectations and the End of the Depression American Economic Review 98(4) (September 2008): 1476–1516). Retrieved July 27, 2024.

- ↑ Peter Temin, Lessons from the Great Depression (MIT Press, 1991, ISBN 978-0262700443).

- ↑ Ludwig von Mises, The Causes of the Economic Crisis: And Other Essays Before and After the Great Depression (Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2006, ISBN 978-1933550039).

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Murray Rothbard, America's Great Depression (Martino Fine Books, 2019, (original 1963), ISBN 978-1684223077).

- ↑ John Cunningham Wood and Robert D. Wood (eds.), Friedrich A. Hayek (Routledge, 2004, ISBN 978-0415310550).

- ↑ Diego Pizano, Conversations with Great Economists: Friedrich A. Hayek, John Hicks, Nicholas Kaldor, Leonid V. Kantorovich, Joan Robinson, Paul A.Samuelson, Jan Tinbergen (Jorge Pinto Books, 2009, ISBN 978-1934978207).

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 William T. Foster and Waddill Catchings, The Road to Plenty (Kessinger Publishing, 2010 (original 1928), ISBN 978-1161391046).

- ↑ Lewis Corey, The Decline of American Capitalism (Forgotten Books, 2018 (original 1934), ISBN 978-0260577122).

- ↑ Bruce Bartlett, The idea that capitalism caused the Great Depression was widely held among intellectuals and the general public for many decades Forbes (July 11, 2012). Retrieved July 27, 2024.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 J. Bradford De Long, "Liquidation" Cycles: Old Fashioned Real Business Cycle Theory and the Great Depression National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 3546, December 1990. Retrieved July 27, 2024.

- ↑ Milton Friedman, Business Cycles interviewed in Barron’s (August 24, 1998). Retrieved July 27, 2024.

- ↑ W.S. Woytinsky and E.S. Woytinsky, World Population and Production: Trends and Outlook (The Twentieth Century Fund, 1953).

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Denyse Baillargeon, Making Do: Women, Family and Home in Montreal during the Great Depression (Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0889203266).

- ↑ Ann E. McCleary, "I Was Really Proud of Them: Canned Raspberries and Home Production During the Farm Depression". Augusta Historical Bulletin (46) (2010): 14–44.

- ↑ Feedsacks and the Great Depression TRC Online Exhibitions. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

- ↑ Teri Klassen, How Depression-Era Quiltmakers Constructed Domestic Space: An Interracial Processual Study Midwestern Folklore 34(2) (2008): 17–47. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

- ↑ Mark Metzler, Woman's Place in Japan's Great Depression: Reflections on the Moral Economy of Deflation Journal of Japanese Studies 30(2) (2004): 315–352. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

- ↑ Nancy R. Reagin, Marktordnung and Autarkic Housekeeping: Housewives and Private Consumption under the Four-Year Plan, 1936–1939 German History 19(2) (April 2001): 162–184. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

- ↑ Betty S. Anderson, A History of the Modern Middle East: Rulers, Rebels, and Rogues (Stanford University Press, 2016, ISBN 978-0804783248).

- ↑ Adam Tooze, The Wages of Destruction: The Making and Breaking of the Nazi Economy (Penguin Books, 2008, ISBN 978-0143113201).

- ↑ Ian Kershaw, To Hell and Back: Europe 1914–1949 (Penguin Books, 2016, ISBN 978-0143109921).

- ↑ A.J.H. Latham, The Depression and the Developing World, 1914–1939 (Routledge, 2006 (original 1981), ISBN 978-0415392679).

- ↑ R. Olufeni Ekundare, An Economic History of Nigeria 1860–1960 (Methuen, 1973, ISBN 978-0416751505).

- ↑ Harry Gamble, Les paysans de l'empire: écoles rurales et imaginaire colonial en Afrique occidentale française dans les années 1930 (Peasants of the Empire. Rural Schools and the Colonial Imaginary in 1930s French West Africa) Cahiers d'Études Africaines 49(3) (2009): 775–803. Retrieved July 28, 2024.

- ↑ Rosemary Thorp (ed.), Latin America in the 1930s: The role of the periphery in world crisis (Palgrave Macmillan, 1984, ISBN 0333365720).

- ↑ Robert William Davies, Mark Harrison, and Stephen G. Wheatcroft (eds.), The Economic Transformation of the Soviet Union, 1913–1945 (Cambridge University Press, 1993, ISBN 978-0521451529).

- ↑ Jennifer Burns, Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right (Oxford University Press, 2009, ISBN 0195324870).

- ↑ Stephen Constantine, Social Conditions in Britain 1918–1939 (Routledge, 1983, ISBN 978-0416360103).

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Peter Clements, Prosperity, Depression and the New Deal: The USA 1890-1954 (Hodder Education Publishers, 2008, ISBN 978-0340965887).

- ↑ Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., The Coming of the New Deal: 1933–1935 (Mariner Books, 2003 (original 1958), ISBN 978-0618340866).

- ↑ John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath 75th Anniversary Edition (Viking, 2014 (original 1939), ISBN 978-0670016907).

- ↑ David A. Taylor, Soul of a People: The WPA Writers' Project Uncovers Depression America (Trade Paper Press, 2009, ISBN 978-1684425204).

- ↑ Stephen Pimpare, Ghettos, Tramps, and Welfare Queens: Down and Out on the Silver Screen (Oxford University Press, 2017, ISBN 978-0190660727).

- ↑ Robert W. Smith, Spotlight on America: The Great Depression (Teacher Created Resources, 2006, ISBN 978-1420632187).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Adelman, Jeremy, Elizabeth Pollard, Clifford Rosenberg, and Robert Tignor. Worlds Together, Worlds Apart: A History of the World from the Beginnings of Humankind to the Present. W. W. Norton & Company, 2021. ISBN 978-0393532043

- Anderson, Betty S. A History of the Modern Middle East: Rulers, Rebels, and Rogues. Stanford University Press, 2016. ISBN 978-0804783248

- Ashworth, William. A Short History of the International Economy Since 1850. Hassell Street Press, 2021. ISBN 978-1013897023

- Baillargeon, Denyse. Making Do: Women, Family and Home in Montreal during the Great Depression. Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0889203266

- Blum, Jerome, Rondo Cameron, and Thomas G. Barnes. The European World: A History (2nd ed). Little, Brown, 1970. ISBN 978-0316100274

- Burns, Jennifer. Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right. Oxford University Press, 2009. ISBN 0195324870

- Clements, Peter. Prosperity, Depression and the New Deal: The USA 1890-1954. Hodder Education Publishers, 2008. ISBN 978-0340965887

- Constantine, Stephen. Social Conditions in Britain 1918–1939. Routledge, 1983. ISBN 978-0416360103

- Corey, Lewis. The Decline of American Capitalism. Forgotten Books, 2018 (original 1934). ISBN 978-0260577122

- Davies, Robert William, Mark Harrison, and Stephen G. Wheatcroft (eds.). The Economic Transformation of the Soviet Union, 1913–1945. Cambridge University Press, 1993. ISBN 978-0521451529

- Eichengreen, Barry. Golden Fetters: The Gold Standard and the Great Depression, 1919–1939. Oxford University Press, 1992. ISBN 978-0195101133

- Ekundare, R. Olufeni. An Economic History of Nigeria 1860–1960. Methuen, 1973. ISBN 978-0416751505

- Ferguson, Niall. The Ascent of Money. Penguin Books, 2009. ISBN 978-0143116172

- Fisher, Irving. The Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions. Martino Fine Books, 2011 (original 1933). ISBN 978-1614270102

- Foster, William T., and Waddill Catchings. The Road to Plenty. Kessinger Publishing, 2010 (original 1928). ISBN 978-1161391046

- Frank, Robert H., and Ben S. Bernanke, Principles of Macroeconomics. McGraw-Hill Education, 2012. ISBN 978-0077318505

- Freidel, Frank. Franklin D. Roosevelt: Launching the New Deal. Little Brown & Co, 1973. ISBN 978-0316293037

- Friedman, Milton, and Anna Jacobson Schwartz. A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960. Princeton University Press, 1971. ISBN 978-0691003542

- Garraty, John A. The Great Depression. Anchor, 1987. ISBN 978-0385240857

- Glynn, Sean, and John Oxborrow. Interwar Britain: A social and economic history. Allen & Unwin, 1976. ISBN 978-0049421417

- Kershaw, Ian. To Hell and Back: Europe 1914–1949. Penguin Books, 2016. ISBN 978-0143109921

- Latham, A.J.H. The Depression and the Developing World, 1914–1939. Routledge, 2006 (original 1981). ISBN 978-0415392679

- Manchester, William. The Glory and the Dream: A Narrative History of America, 1932–1972. Little Brown & Co, 1974. ISBN 978-0316544962

- Mises, Ludwig von. The Causes of the Economic Crisis: And Other Essays Before and After the Great Depression. Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2006. ISBN 978-1933550039

- Mitchell, Broadus. Depression Decade: From New Era Through New Deal, 1929-1941. Routledge, 2017. ASIN B073RQCWFB

- Parker, Randall E. Reflections on the Great Depression. Edward Elgar Publishing, 2002. ISBN 1840647450

- Pimpare, Stephen. Ghettos, Tramps, and Welfare Queens: Down and Out on the Silver Screen. Oxford University Press, 2017. ISBN 978-0190660727

- Pizano, Diego. Conversations with Great Economists: Friedrich A. Hayek, John Hicks, Nicholas Kaldor, Leonid V. Kantorovich, Joan Robinson, Paul A.Samuelson, Jan Tinbergen. Jorge Pinto Books, 2009. ISBN 978-1934978207

- Robbins, Lionel. The Great Depression. Routledge, 2009 (original 1934). ISBN 978-1412810081

- Rosenof, Theodore. Economics in the Long Run: New Deal Theorists and Their Legacies, 1933–1993. University of North Carolina Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0807823156

- Rothbard, Murray. America's Great Depression. Martino Fine Books, 2019, (original 1963). ISBN 978-1684223077

- Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr. The Coming of the New Deal: 1933–1935. Mariner Books, 2003 (original 1958). ISBN 978-0618340866

- Smith, Robert W. Spotlight on America: The Great Depression. Teacher Created Resources, 2006. ISBN 978-1420632187

- Soule, George H. Prosperity Decade: From War to Depression: 1917–1929. Routledge, 1977. ISBN 0873320980

- Steinbeck, John. The Grapes of Wrath 75th Anniversary Edition. Viking, 2014 (original 1939). ISBN 978-0670016907

- Taylor, David A. Soul of a People: The WPA Writers' Project Uncovers Depression America. Trade Paper Press, 2009. ISBN 978-1684425204

- Temin, Peter. Lessons from the Great Depression. MIT Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0262700443

- Thorp, Rosemary (ed.)., Latin America in the 1930s: The role of the periphery in world crisis. Palgrave Macmillan, 1984. ISBN 0333365720

- Tooze, Adam. The Wages of Destruction: The Making and Breaking of the Nazi Economy. Penguin Books, 2008. ISBN 978-0143113201

- Wood, John Cunningham, and Robert D. Wood (eds.). Friedrich A. Hayek. Routledge, 2004. ISBN 978-0415310550

- Woytinsky, W.S., and E.S. Woytinsky, World Population and Production: Trends and Outlook. The Twentieth Century Fund, 1953. ASIN B000OHGLJI

External links

All links retrieved July 23, 2024

- Great Depression History.com

- Great Depression History History.com

- Great Depression Facts FDR Library & Museum

- The Great Depression: Overview, Causes, and Effects Investopedia

- Americans React to the Great Depression Library of Congress

- The Great Depression: 1929–1941 Federal Reserve History

- The Great Depression and U.S. Foreign Policy Office of the Historian

- Great Depression By Gene Smiley, The Library of Economics and Liberty

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.