| Halifax | |

| ‚ÄĒ¬†¬†Regional Municipality¬†¬†‚ÄĒ | |

| Halifax Regional Municipality | |

| Halifax, Nova Scotia | |

| Motto: "E Mari Merces" (Latin) "From the Sea, Wealth" |

|

| Location of Halifax Regional Municipality | |

| Coordinates: 44¬į51‚Ä≤N 63¬į12‚Ä≤W | |

|---|---|

| Country | Canada |

| Province | Nova Scotia |

| Established | April 1, 1996 |

| Government | |

|  - Type | Regional Municipality |

|  - Mayor | Peter Kelly |

|  - Governing body | Halifax Regional Council |

|  - MPs | List of MPs

|

|  - MLAs | List of MLAs

|

| Area [1] | |

|  - Land | 5,490.18 km² (2,119.8 sq mi) |

|  - Urban | 262.65 km² (101.4 sq mi) |

|  - Rural | 5,528.25 km² (2,134.5 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 145 m (475.6 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

|  - Regional Municipality | 390,096 (14th) |

|  - Density | 71.1/km² (184.1/sq mi) |

|  - Urban | 290,742 |

|  - Urban Density | 1,077.2/km² (2,789.9/sq mi) |

|  - Metro | 390,096 (13th) |

|  - Change 2006-2011 | |

|  - Census Ranking | 13 of 5,008 |

| Time zone | AST (UTC‚ąí4) |

| ¬†-¬†Summer¬†(DST) | ADT (UTC‚ąí3) |

| Area code(s) | 902 |

| Dwellings | 166,675 |

| Median Income* | $54,129 CDN |

| Total Coastline | 400 km (250 mi) |

| NTS Map | 011D13 |

| GNBC Code | CBUCG |

| *Median household income, 2005 (all households) | |

| Website: www.halifax.ca | |

The City of Halifax is the largest city in Atlantic Canada and the traditional political capital of the province of Nova Scotia. Founded in 1749 by Great Britain, the "City of Halifax" was incorporated in 1841. An important East coast port and center of maritime commerce and fishing, both Halifax's history and economy have been tied to the booms and busts of its Atlantic location.

On April 1, 1996, the government of Nova Scotia amalgamated the four municipalities within Halifax County and formed Halifax Regional Municipality, a single-tier regional government covering that whole area.

History

Early period

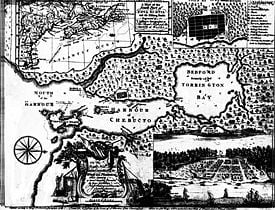

The Mi'kmaq aboriginal peoples called the area "Jipugtug" (anglicized as "Chebucto"), which means "the biggest harbor" in reference to large sheltered port. There is evidence that native bands would spend the summer on the shores of the Bedford Basin, moving to points inland before the harsh Atlantic winter began. Examples of Mikmaq habitation and burial sites have been found throughout Halifax, from Point Pleasant Park to the north and south mainland.

In the wake of French exploration of the area, some French settlers intermarried with the native population establishing Acadian settlements in Minas and Pizquid. French warships and fishing vessels, requiring shelter and a place to draw water, certainly visited the harbor. The territory, which included much of the present-day Maritimes and Gaspé Peninsula, passed from French to English and even Scottish hands several times. In the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht, Acadia was relinquished to England, however the boundaries of the ceasefire were imprecise, leaving England with what is today peninsular Nova Scotia, and France with control of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. The colonial capital chosen was Annapolis Royal. In 1717, France began a 20-year effort to build a large fortified seaport at Louisbourg on present-day Cape Breton Island which was intended as a naval base for protecting the entrance to the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and extensive fishing grounds on the Grand Banks.

In 1745, Fortress Louisbourg fell to a New England-led force. In 1746 Admiral Jean-Batiste, De Roye de la Rochefoucauld, Duc d'Enville, was dispatched by the King of France in command of a French Armada of 65 ships. He was dispatched to undermine the English position in the new world, specifically at Louisbourg, Annapolis Royal, and most likely the eastern seaboard of the Thirteen Colonies.

The fleet was to meet in Chebucto (Halifax Harbour) on British-held peninsular Nova Scotia after crossing the Atlantic, take water and proceed to Louisbourg. Unfortunately, two major storms kept the fleet at sea for over three months. Poor water and spoiled food further weakened the exhausted fleet, resulting in the death of at least 2,500 men, including Duc d'Anville himself, by the time it arrived at Chebucto. After a series of calamities the fleet returned to France, its mission unfulfilled. For decades after, the skeletal remains of the desperate, despairing French soldiers and sailors were reportedly found on the shores and in the woods around Halifax by later settlers and their descendants. The ghost of Duc d'Anville is said to haunt George's Island, his original burial place, to this day.

English settlement

Between the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713 and 1749, no serious attempts were made by Great Britain to colonize Nova Scotia, aside from its presence at Annapolis Royal and infrequent sea and land patrols. The peninsula was dominated by Acadian residents and the need for a permanent settlement and British military presence on the central Atlantic coast of peninsular Nova Scotia was recognized, but it took the negotiated return of Fortress Louisbourg to France in 1748 to prod Britain into action. British General Edward Cornwallis was dispatched by the Lords of Trade and Plantations to establish a city at Chebucto, on behalf of and at the expense of the Crown. Cornwallis sailed in command of 13 transports, a sloop of war, 1,176 settlers and their families.

Halifax was founded on June 21, 1749 below a glacial drumlin that would later be named Citadel Hill. The outpost was named in honor of George Montague-Dunk, 2nd Earl of Halifax, who was the President of the British Board of Trade. Halifax was ideal for a military base, as it has what is claimed to be the second largest natural harbor in the world, and could be well protected with batteries at McNab's Island, the North West Arm, Point Pleasant, George's Island and York Redoubt. In its early years, Citadel Hill was used as a command and observation post, prior to changes in artillery which could range out into the harbor.

The town proved its worth as a military base in the Seven Years War as a counter to the French fortress Louisbourg in Cape Breton. Halifax provided the base for the capture of Louisbourg in 1758 and operated as a major naval base for the remainder of the war. For much of this period in the early 1700s, Nova Scotia was considered a hardship posting for the British military, given the proximity to the border with French territory and potential for conflict; the local environment was also very inhospitable and many early settlers were ill-suited for the colony's virgin wilderness on the shores of Halifax Harbour. The original settlers, who were often discharged soldiers and sailors, left the colony for established cities such as New York and Boston or the lush plantations of the Virginias and Carolinas. However, the new city did attract New England merchants exploiting the near-by fisheries and English merchants such as Joshua Maugher who profited greatly from both British military contracts and smuggling with the French at Louisbourg. The military threat to Nova Scotia was removed following British victory over France in the Seven Years War.

With the addition of remaining territories of the colony of Acadia, the enlarged British colony of Nova Scotia was mostly depopulated, following the deportation of Acadian residents. In addition, Britain was unwilling to allow its residents to emigrate, this being at the dawn of their Industrial Revolution, thus Nova Scotia was opened up settlement to "foreign Protestants." The region, including its new capital of Halifax, saw a modest immigration boom comprising Germans, Dutch, New Englanders, residents of Martinique and many other areas. In addition to the surnames of many present-day residents of Halifax who are descended from these settlers, an enduring name in the city is the "Dutch Village Road," which led from the "Dutch Village," located in Fairview.

The American Revolution and after

Halifax's fortunes waxed and waned with the military needs of the Empire. While it had quickly become the largest Royal Navy base on the Atlantic coast and had hosted large numbers of British army regulars, the complete destruction of Louisbourg in 1760 removed the threat of French attack. Crown interest in Halifax was reduced, and most importantly, New England turned its eyes west, to the French territory now available due to the defeat of Montcalm at the Plains of Abraham. By the mid 1770s the town was feeling its first of many peacetime slumps.

The American Revolutionary War was not at first uppermost in the minds of most residents of Halifax. The government did not have enough money to pay for oil for the Sambro lighthouse. The militia was unable to maintain a guard, and was disbanded. Provisions were so scarce during the winter of 1775 that Quebec had to send flour to feed the town. While Halifax was remote from the troubles in the rest of the American colonies, martial law was declared in November 1775 to combat lawlessness.

On March 30, 1776, General William Howe arrived, having been driven from Boston by rebel forces. He brought with him 200 officers, 3000 men, and over 4,000 loyalist refugees, and demanded housing and provisions for all. This was merely the beginning of Halifax's role in the war. Throughout the conflict, and for a considerable time afterwards, thousands more refugees, often 'in a destitute and helpless condition'2 had arrived in Halifax or other ports in Nova Scotia. This would peak with the evacuation of New York, and continue until well after the formal conclusion of war in 1783. At the instigation of the newly-arrived Loyalists who desired greater local control, Britain subdivided Nova Scotia in 1784 with the creation of the colonies of New Brunswick and Cape Breton Island; this had the effect of considerably diluting Halifax's presence over the region.

During the American Revolution, Halifax became the staging point of many attacks on rebel-controlled areas in the Thirteen Colonies, and was the city to which British forces from Boston and New York were sent after the over-running of those cities. After the War, tens of thousands of United Empire Loyalists from the American Colonies flooded Halifax, and many of their descendants still reside in the city today.

Halifax was now the bastion of British strength on the East Coast of North America. Local merchants also took advantage of the exclusion of American trade to the British colonies in the Caribbean, beginning a long trade relationship with the West Indies. However, the most significant growth began with the beginning of what would become known as the Napoleonic Wars. By 1794, Prince Edward, Duke of Kent, was sent to take command of Nova Scotia. Many of the cities forts were designed by him, and he left an indelible mark on the city in the form of many public buildings of Georgian architecture, and a dignified British feel to the city itself. It was during this time that Halifax truly became a city. Many landmarks and institutions were built during his tenure, from the Town Clock on Citadel Hill to Saint George's Round Church, fortifications in the Halifax Defence Complex were built up, businesses established, and the population boomed.

Though the Duke left in 1800, the city continued to experience considerable investment throughout the Napoleonic Wars and War of 1812. Although Halifax was never attacked during the war of 1812, due to the overwhelming military presence in the city, many Naval battles occurred just outside the harbor. Most dramatic was the victory of the Halifax-based British frigate HMS Shannon which captured the American frigate USS Chesapeake and brought her to Halifax as prize. As well, an invasion force which attacked Washington in 1813, and burned the Capitol and White House was sent from Halifax. Early in the War, an expedition under Lord Dalhousie left Halifax to capture the Area of Castine, Maine, which they held for the entirety of the war. The revenues which were taken from this invasion were used after the war to found Dalhousie University which is today Halifax's largest university. The city also thrived in the War of 1812 on the large numbers of captured American ships and cargoes captured by the British navy and provincial privateers.

Saint Mary's University was founded in 1802, originally as an elementary school. Saint Mary's was upgraded to a college following the establishment of Dalhousie in 1818; both were initially located in the downtown central business district before relocating to the then-outskirts of the city in the south end near the Northwest Arm. Separated by only few minutes walking distance, the two schools now enjoy a friendly rivalry.

Present day government landmarks such as Government House, built to house the governor, and Province House, built to house the House of Assembly, were both built during the city's boom during this wartime period.

In the peace after 1815, the city suffered an economic malaise for a few years, aggravated by the move of the Royal Naval yard to Bermuda in 1818. However the economy recovered in the next decade led by a very successful local merchant class. Powerful local entrepreneurs included steamship pioneer Samuel Cunard and the banker Enos Collins. During the 1800s Halifax became the birthplace of two of Canada's largest banks; local financial institutions included the Halifax Banking Company, Union Bank of Halifax, People's Bank of Halifax, Bank of Nova Scotia, and the Merchants' Bank of Halifax, making the city one of the most important financial centres in colonial British North America and later Canada until the beginning of the twentieth century. This position was somewhat rivalled by neighboring Saint John, New Brunswick where that city's Princess Street laid claim to being the "Wall Street of Canada" during the city's economic hey-day in the mid-nineteenth century.

Having played a key role to maintain and expand British power in North America and elsewhere during the eighteenth century, Halifax played less dramatic roles in the consolidation of the British Empire during the nineteenth century. The harbor's defenses were successively refortified with the latest artillery defenses throughout the century to provide a secure base for British Empire forces. Nova Scotian and Maritimers were recruited through Halifax for the Crimean War. The city boomed during the American Civil War, mostly by supplying the wartime economy of the North but also by offering refuge and supplies to Confederate blockade runners. The port also saw Canada's first overseas military deployment as a nation to aid the British Empire during the Second Boer War.

Incorporation, responsible government, railways and Confederation

Later considered a great Nova Scotian leader, and the father of responsible government in British North America, it was the cause of self government for the city of Halifax that began the political career of Joseph Howe and would subsequently lead to this form of accountability being brought to colonial affairs for the colony of Nova Scotia. After election to the House of Assembly as leader of the Liberal party, one of his first acts was the incorporation of the City of Halifax in 1842, followed by the direct election of civic politicians by Haligonians.

Halifax became a hotbed of political activism as the winds of responsible government swept British North America during the 1840s, following the rebellions against oligarchies in the colonies of Upper and Lower Canada. The first instance of responsible government in the British Empire was achieved by the colony of Nova Scotia in January-February 1848 through the efforts of Howe. The leaders of the fight for responsible or self-government later took up the Anti-Confederation fight, the movement that from 1868 to 1875 tried to take Nova Scotia out of Confederation.

During the 1850s, Howe was a heavy promoter of railway technology, having been a key instigator in the founding of the Nova Scotia Railway, which ran from Richmond in the city's north end to the Minas Basin at Windsor and to Truro and on to Pictou on the Northumberland Strait. In the 1870s Halifax became linked by rail to Moncton and Saint John through the Intercolonial Railway and on into Quebec and New England, not to mention numerous rural areas in Nova Scotia.

The American Civil War again saw much activity and prosperity in Halifax. Merchants in the city made huge profits selling supplies and arms to both sides of the conflict (see for example Alexander Keith, Jr.), and Confederate ships often called on the port to take on supplies, and make repairs. One such ship, the Tallahassee, became a legend in Halifax as it made a daring escape from Federal frigates heading to Halifax to capture it.

After the American Civil War, the five colonies which made up British North America, Ontario, Quebec, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, held meetings to consider Uniting into a single country. This was due to a threat of annexation and invasion from the United States. Canadian Confederation became a reality in 1867, but received much resistance from the merchant classes of Halifax, and from many prominent Halifax politicians due to the fact that both Halifax and Nova Scotia were at the time very wealthy, held trading ties with Boston and New York which would be damaged, and did not see the need for the Colony to give up its comparative independence. After confederation Halifax retained its British military garrison until British troops were replaced by the Canadian army in 1906. The British Royal Navy remained until 1910 when the newly created Canadian Navy took over the Naval Dockyard.

World War I

It was during World War I that Halifax would truly come into its own as a world class port and naval facility. The strategic location of the port with its protective waters of Bedford Basin sheltered convoys from German U-boat attack prior to heading into the open Atlantic Ocean. Halifax's railway connections with the Intercolonial Railway of Canada and its port facilities became vital to the British war effort during the First World War as Canada's industrial centres churned out material for the Western Front. In 1914, Halifax began playing a major role in the First World War, both as the departure point for Canadian Soldiers heading overseas, and as an assembly point for all convoys (a responsibility which would be placed on the city again during WW2).

Halifax Explosion

The war was seen as a blessing for the city's economy, but in 1917 a French munitions ship, the Mont Blanc, collided with a Belgian relief ship, the Imo. The collision sparked a fire on the munitions ship which was filled with TNT, and gun cotton. On December 6, 1917, at 9am the munitions ship exploded in what was the largest man-made explosion before the first testing of an atomic bomb, and is still one of the largest non-nuclear man-made explosions. The Halifax Explosion decimated the city's north end, killing roughly 2,000 inhabitants, injuring 9,000, and leaving tens of thousands homeless and without shelter.

The following day a blizzard hit the city, crippling recovery efforts. Immediate help rushed in from the rest of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland. In the following week more relief from other parts of North America arrived and donations were sent from around the world. The most celebrated effort came from the Boston Red Cross and the Massachusetts Public Safety Committee; as an enduring thank-you, for the past 30 years the province of Nova Scotia has donated the annual Christmas tree lit on the Boston Common.

Between the Wars

The city's economy slumped after the war, although reconstruction from the Halifax Explosion brought new housing and infrastructure as well as the establishment of the Halifax Shipyard. However, a tremendous drop in worldwide shipping following the war as well as the failure of regional industries in the 1920s brought hard-times to the city, further aggravated by the Great Depression in 1929. One bright spot was the completion of Ocean Terminals in the city's south end, a large modern complex to trans-ship freight and passengers from steamships to railways.

World War II

Halifax played an even bigger role in the Allied naval war effort of World War II. The only theatre of War to be commanded by a Canadian was the North Western Atlantic, commanded by the Admiral in Halifax. Halifax became a lifeline for preserving Britain during the Nazi onslaught of the Battle of Britain and the Battle of the Atlantic, the supplies helping to offset a threatened amphibious invasion by Germany. Many convoys assembled in Bedford Basin to deliver supplies to troops in Europe. The city's railway links fed large numbers of troopships building up Allied armies in Europe. The harbor became an essential base for Canadian, British and other Allied warships. Very much a front-line city, civilians lived with the fears of possible German raids or another accidental ammunition explosion. Well defended, the city was never attacked although some merchant ships and two small naval vessels were sunk at the outer approaches to the harbor. However, the sounds and sometimes the flames of these distant attacks fed wartime rumors, some of which linger to the present day of imaginary tales of German U-Boats entering Halifax Harbour. The city's housing, retail and public transit infrastructure, small and neglected after 20 years of prewar economic stagnation was severely stressed. Severe housing and recreational problems simmered all through the war and culminated in a large-scale riot by military personnel on VE Day in 1945.

Post-war

After World War Two, Halifax did not experience the postwar economic malaise it had so often experienced after previous wars. This was partially due to the Cold War which required continued spending on a modern Canadian Navy. However, the city also benefitted from a more diverse economy and postwar growth in government services and education. The 1960s-1990s saw less suburban sprawl than in many comparable Canadian cities in the areas surrounding Halifax. This was partly as a result of local geographies and topography (Halifax is extremely hilly with exposed granite‚ÄĒnot conducive to construction), a weaker regional and local economy, and a smaller population base than, for example, central Canada or New England. There were also deliberate local government policies to limit not only suburban growth but also put some controls on growth in the central business district to address concerns from heritage advocates.

The late 1960s was a period of significant change and expansion of the city when surrounding areas of Halifax County were amalgamated into Halifax: Rockingham, Clayton Park, Fairview, Armdale, and Spryfield were all added in 1969.

Halifax suffered the effects of short-sighted urban renewal plans in the 1960s and 1970s with the loss of much of its heritage architecture and community fabric in large downtown developments such as the Scotia Square mall and office towers. However, a citizens protest movement limited further destructive plans such as a waterfront freeway which opened the way for a popular and successful revitalized waterfront. Selective height limits were also achieved to protect the views from Citadel Hill. However, municipal heritage protection has remained weak with only pockets of heritage buildings surviving in the downtown and constant pressure from developers for further demolition.

Another casualty during this period of expansion and urban renewal was the Black community of Africville which was demolished and its residents displaced to clear land for industrial use, as well as for the A. Murray MacKay Bridge. The repercussions continue to this day and a 2001 United Nations report has called for reparations to be paid to the community's former residents.

Restrictions on development were relaxed somewhat during the 1990s, resulting in some suburban sprawl off the peninsula. Today the community of Halifax is more compact than most Canadian urban areas although expanses of suburban growth have occurred in neighboring Dartmouth, Bedford and Sackville. One development in the late 1990s was the Bayers Lake Business Park, where warehouse style retailers were permitted to build in a suburban industrial park west of Rockingham. This has become an important yet controversial centre of commerce for the city and the province as it used public infrastructure to subsidize multi-national retail chains and draw business from local downtown business. Much of this short-sighted subsidy was due to competition between Halifax, Bedford and Dartmouth to host these giant retail chains and this controversy helped lead the province to force amalgamation as a way to end wasteful municipal rivalries. In the past few years, urban housing sprawl has even reached these industrial/retail parks as new blasting techniques permitted construction on the granite wilderness around the city. What was once a business park surrounded by forest and a highway on one side has become a large suburb with numerous new apartment buildings and condominiums. Some of this growth has been spurred by offshore oil and natural gas economic acitivity but much has been due to a population shift from rural Nova Scotian communities to the Halifax urban area. The new amalgamated city has attempted to manage this growth with a new master development plan.

Amalgamation

During the 1990s, Halifax like many other Canadian cities, amalgamated with its suburbs under a single municipal government. The provincial government had sought to reduce the number of municipal governments throughout the province as a cost-saving measure and created a task force in 1992 to pursue this rationalization.

In 1995, an Act to Incorporate the Halifax Regional Municipality received Royal Assent in the provincial legislature and the Halifax Regional Municipality, or "HRM" (as it is commonly called) was created on April 1, 1996. HRM is an amalgamation of all municipal governments in Halifax County, these being the cities of Halifax and Dartmouth, town of Bedford, and Municipality of the County of Halifax). Sable Island, being part of Halifax County, is also jurisdictionally part of HRM, despite being located 180 km offshore.

Although cities in other provinces affected by amalgamation retained their original names, the new municipality is often referred by its full name or the initials "HRM" especially in the media and by residents of areas outside of the former City of Halifax. However, communities outside of the former City of Halifax still retained their original placenames to avoid confusion with duplicate street names for emergency, postal and other services.

Geography

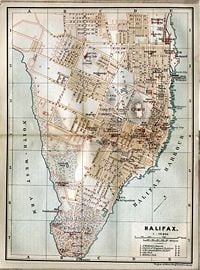

The original settlements of Halifax occupied a small stretch of land inside a palisade at the foot of Citadel Hill on the Halifax Peninsula, a sub-peninsula of the much larger Chebucto Peninsula that extends into Halifax Harbour. Halifax subsequently grew to incorporate all of the north, south, and west ends of the peninsula with a central business district concentrated in the southeastern end along "The Narrows."

In 1969, the City of Halifax grew westward of the peninsula by amalgamating several communities from the surrounding Halifax County; namely Fairview, Rockingham, Spryfield, Purcell's Cove, and Armdale. These communities saw a number of modern subdivision developments during the late 1960s through to the 1990s, one of the earliest being the Clayton Park development at the southwestern edge of Rockingham.

Since amalgamation into HRM, "Halifax" has been used variously to describe all HRM, all of urban HRM, and the area of the Halifax Peninsula and Mainland Halifax (which together form the provincially recognized Halifax Metropolitan Area) that had been covered by the dissolved city government.[1][2][3][4]

The communities of mainland Halifax that were amalgamated into the City of Halifax in 1969 are reasserting their identities [5][6][7] principally through the creation of the Mainland Halifax planning area, which is governed by the Chebucto Community Council.

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ 1.0 1.1 2006 Statistics Canada Community Profile: Halifax Regional Municipality, Nova Scotia. 2.statcan.ca (2010-12-07). Retrieved April 20, 2012.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Akins, Thomas B. History of Halifax City: Illustrated with maps and engravings (Canadiana reprint series). Mika Pub, 1973. ISBN 0919302637

- McCann, L.D. "Halifax" The Canadian Encyclopedia (2000 edition) Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1999, 1034-1036

- Raddall, Thomas. Halifax- Warden of the North. Doubleday & Co., Inc. (original 1949) 1965. ASIN B000ONJ5D6

External links

All links retrieved June 22, 2024.

- Government House, Halifax Sights & Activities, Fodor's Online Travel Guide.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.