| Chinese character | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese: | 漢字 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese: | 汉字 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji: | 漢字 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Kana: | かんじ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Romaji: | kanji | ||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul: | 한자 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja: | 漢字 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||

| Quoc Ngu: | Hán Tự (Sino-Viet.) Chữ Nho (native tongue) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Hantu: | 漢字 (Sino-Viet.) 字儒 (native tongue) | ||||||||||||||||||

A Chinese character (Simplified Chinese: 汉字; Traditional Chinese: 漢字; pinyin: Hànzì) is a logogram used in writing Chinese, Japanese, sometimes Korean, and formerly Vietnamese. Four percent of Chinese characters are derived directly from individual pictograms (Chinese: 象形字; pinyin: xiàngxíngzì), but most characters are pictophonetics (Simplified Chinese: 形声字; Traditional Chinese: 形聲字; pinyin: xíng-shēngzì), characters containing two parts where one indicates a general category of meaning and the other the sound. There are approximately 50,000 Chinese characters in existence, but only between three and four thousand are in regular use.

The oldest Chinese inscriptions that are indisputably writing are the Oracle Bone Script (Chinese: 甲骨文; pinyin: jiǎgǔwén; literally "shell-bone-script"), a well-developed writing system dating to the late Shang Dynasty (1200-1050 B.C.E.). Some believe that Chinese compound characters including above-mentioned pictophonetics carry profound meanings that can be divined from the component parts of the compound, and believe that they, like the oracles from which they came, were invented through some kind of revelation from above.

Chinese calligraphy, the art of writing Chinese characters, is usually done with ink brushes. In Asia, calligraphy is appreciated for its aesthetic beauty, but also as an expression of the inner nature of the calligrapher who creates it.

| This article contains Chinese text. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Chinese characters. |

Chinese Characters

The number of Chinese characters contained in the Kangxi dictionary is approximately 47,035, although a large number of these are rarely-used variants accumulated throughout history. Studies carried out in China have shown that full literacy requires a knowledge of between three and four thousand characters.[1]

In Chinese tradition, each character corresponds to a single syllable. A majority of words in all modern varieties of Chinese are polysyllabic, and writing them requires two or more characters. Cognates in the various Chinese languages and dialects which have the same or similar meaning, but different pronunciations, can be written with the same character. In addition, many characters were adopted according to their meaning by the Japanese and Korean languages to represent native words, disregarding pronunciation altogether. The loose relationship between phonetics and characters has thus made it possible for them to be used to write very different and probably unrelated languages.

Four percent of Chinese characters are derived directly from individual pictograms (Chinese: 象形字; pinyin: xiàngxíngzì), and in most of those cases the relationship is not necessarily clear to the modern reader. Of the remaining 96 percent, some are logical aggregates (Simplified Chinese: 会意字; Traditional Chinese: 會意字; pinyin: huìyìzì), which are characters combined from multiple parts indicative of meaning. But most characters are pictophonetics (Simplified Chinese: 形声字; Traditional Chinese: 形聲字; pinyin: xíng-shēngzì), characters containing two parts where one indicates a general category of meaning and the other the sound. The sound in such characters is often only approximate to the modern pronunciation because of changes over time and differences between source languages.

Just as Roman letters have a characteristic shape (lower-case letters occupying a roundish area, with ascenders or descenders on some letters), Chinese characters occupy a more or less square area. Characters made up of multiple parts fit these parts together within an area of uniform size and shape; this is the case especially with characters written in the Sòngtǐ style. Because of this, beginners often practice on squared graph paper, and the Chinese sometimes use the term "Square-Block Characters." (Simplified Chinese: 方块字; Traditional Chinese: 方塊字; pinyin: fāngkuàizì).

The actual content and style of many Chinese characters varies in different cultures. Mainland China adopted simplified characters in 1956, but Traditional Chinese characters are still used in Taiwan and Hong Kong. Singapore has also adopted simplified Chinese characters. Postwar Japan has used its own less drastically simplified characters since 1946. South Korea has limited its use of Chinese characters, and Vietnam and North Korea have completely abolished their use in favor of romanized Vietnamese and Hangul, respectively.

Chinese characters are also known as sinographs, and the Chinese writing system as sinography. Non-Chinese languages which have adopted sinography—and, with the orthography, a large number of loanwords from the Chinese language—are known as Sinoxenic languages, whether or not they still use the characters. The term does not imply any genetic affiliation with Chinese. The major Sinoxenic languages are generally considered to be Japanese, Korean and Vietnamese.

History

A complete writing system in Chinese characters appeared in China 3200 years ago during the Shang Dynasty,[2][3][4] making it what is believed to be the oldest surviving writing system. Sumerian cuneiform, which originated about 3200 B.C.E., is currently regarded as being the oldest known writing system.

The oldest Chinese inscriptions that are indisputably writing are the Oracle bone script (Chinese: 甲骨文; pinyin: jiǎgǔwén; literally "shell-bone-script"), a well-developed writing system dating to the late Shang Dynasty (1200-1050 B.C.E.).[2][3][4] The oracle bone inscriptions were discovered at what is now called the Yin Ruins near Anyang city in 1899. A few are from Zhengzhou (鄭州) and date to earlier in the dynasty, around the sixteenth to fourteenth centuries B.C.E., while a very few date to the beginning of the subsequent Zhou dynasty (周朝, Zhōu Chá o, Chou Ch`ao). In addition, there are a small number of logographs found on pottery shards and cast in bronzes, known as the Bronze script (Chinese: 金文; pinyin: jīnwén), which is very similar to but more complex and pictorial than the Oracle Bone Script. These suggest that Oracle Bone Script was a simplified version of more complex characters used in writing with a brush; no examples of writing with ink remain, but the Oracle Bone Script includes characters for bamboo books and brushes, which indicate that they were in use at the time.

Only about 1,400 of the 2,500 known Oracle Bone logographs can be identified with later Chinese characters. However, it should be noted that these 1,400 logographs include most of the commonly used ones. The oracle bone inscriptions were discovered at what is now called the Yin Ruins near Anyang city in 1899. In a 2003 archeological dig at Jiahu in Henan province in western China, various Neolithic signs were found inscribed on tortoise shells which date back as early as the seventh millennium B.C.E., and may represent possible precursors of the Chinese script, although there has been no link established so far.[5]

According to legend, Chinese characters were invented earlier by Cangjie (c. 2650 B.C.E.), a bureaucrat under the legendary emperor, Fu Hsi. The legend tells that Cangjie was hunting on Mount Yangxu (today Shanxi) when he saw a tortoise whose veins caught his curiosity. Inspired by the possibility of a logical relation of those veins, he studied the animals of the world, the landscape of the earth, and the stars in the sky, and invented a symbolic system called zì—Chinese characters. It was said that on the day the characters were born, Chinese heard the devil mourning, and saw crops falling like rain, as it marked the beginning of civilization, for good and for bad.

Emperor Qin Shi Huangdi (259 – 210 B.C.E.), who unified China under the Qin dynasty, created a standard system of writing from the various systems used in the different states of China.

Jiahu Script

A 2003 archeological dig at Jiahu, a Neolithic site in the basin of the Yellow River in Henan province in western China, yielded early Neolithic signs known as the Jiahu script, dated to c. 6500 B.C.E. The script was found on turtle carapaces that were pitted and inscribed with symbols. These signs should not be equated with writing, although they may represent a formative stage of the Chinese script; no link has yet been established.[5]

Although the earliest forms of primitive Chinese writing are no more than individual symbols and therefore cannot be considered a true written script, the inscriptions found on bones (dated to 2500–1900 B.C.E.) used for the purposes of divination from the late Neolithic Longshan (Simplified Chinese: 龙山; Traditional Chinese: 龍山; pinyin: lóngshān) culture (c. 3200–1900 B.C.E.) are thought by some to be a proto-written script, similar to the earliest forms of writing in Mesopotamia and Egypt. It is possible that these inscriptions are ancestral to the later Oracle bone script of the Shang Dynasty and therefore the modern Chinese script, since late Neolithic culture found in Longshan is widely accepted by historians and archaeologists to be ancestral to the Bronze Age Erlitou culture and the later Shang and Zhou dynasties.

At Damaidi in the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, 3172 cliff carvings dating to 6000–5000 B.C.E. have been discovered "featuring 8453 individual characters such as the sun, moon, stars, gods and scenes of hunting or grazing." These pictographs are reputed to resemble the earliest characters confirmed to be written Chinese.[5]

Written Styles

There are numerous styles, or scripts, in which Chinese characters can be written, deriving from various calligraphic and historical models. Most of these originated in China and are now common, with minor variations, in all countries where Chinese characters are used.

The Oracle Bone and Bronzeware scripts being no longer used, the oldest script that is still in use today is the Seal Script (Simplified Chinese: 篆书; Traditional Chinese: 篆書; pinyin: zhuànshū). It evolved organically out of the Zhou bronze script, and was adopted in a standardized form under the first Emperor of China, Qin Shi Huang. The seal script, as the name suggests, is now only used in artistic seals. Few people are still able to read it effortlessly today, although the art of carving a traditional seal in the script remains alive; some calligraphers also work in this style.

Scripts that are still used regularly are the "Clerical Script" (Simplified Chinese: 隸书; Traditional Chinese: 隸書; pinyin: lìshū) of the Qin Dynasty to the Han Dynasty, the Weibei (Chinese: 魏碑; pinyin: wèibēi), the "Regular Script" (Simplified Chinese: 楷书; Traditional Chinese: 楷書; pinyin: kǎishū) used for most printing, and the "Semi-cursive Script" (Simplified Chinese: 行书; Traditional Chinese: 行書; pinyin: xíngshū) used for most handwriting.

The Cursive Script (Simplified Chinese: 草书; Traditional Chinese: 草書; pinyin: cǎoshū) is not in general use, and is a purely artistic calligraphic style. The basic character shapes are suggested, rather than explicitly realized, and the abbreviations are extreme. Despite being cursive to the point where individual strokes are no longer differentiable and the characters often illegible to the untrained eye, this script (also known as draft) is highly revered for the beauty and freedom that it embodies. Some of the Simplified Chinese characters adopted by the People's Republic of China, and some of the simplified characters used in Japan, are derived from the Cursive Script. The Japanese hiragana script is also derived from this script.

There also exist scripts created outside China, such as the Japanese Edomoji styles; these have tended to remain restricted to their countries of origin, rather than spreading to other countries like the standard scripts described above.

Formation of Characters

The early stages of the development of characters were dominated by pictograms, in which meaning was expressed directly by a standard diagram. The development of the script, both to cover words for abstract concepts and to increase the efficiency of writing, has led to the introduction of numerous non-pictographic characters.

The various types of character were first classified c. 100 C.E. by the Chinese linguist Xu Shen, whose etymological dictionary Shuowen Jiezi (說文解字/说文解字) divides the script into six categories, the liùshū (六書/六书): 1) pictograms (象形字 xiàngxíngzì); 2) pictophonetic compounds (形聲字/形声字, Xíngshēngzì); 3) ideograph (指事字, zhǐshìzì); 4) logical aggregates (會意字/会意字, Huìyìzì); 5) associate transformation (轉注字/转注字, Zhuǎnzhùzì); and 6) borrowing (假借字, Jiǎjièzì). While the categories and classification are occasionally problematic and arguably fail to reflect the complete nature of the Chinese writing system, the system has been perpetuated by its long history and pervasive use. Chinese characters in compounds, belonging to the second or fourth group, make sense profoundly when components of each compound are combined meaningwise. For example, 教 (jiāo) for "teaching" is a compound of 孝 (xiào) for "filial piety" and 父 (fù) for "father," with the result that the essence of education is meant to teach about one's filial piety for one's father. From this, many believe that Chinese characters, originally related to oracles in the late Shang Dynasty, were created through some kind of divine revelation.

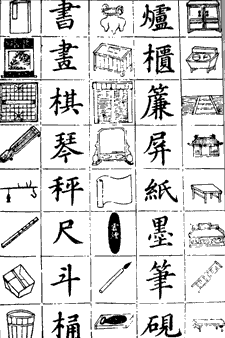

1. Pictograms (象形字 xiàngxíngzì)

Contrary to popular belief, pictograms make up only a small portion of Chinese characters. While characters in this class derive from pictures, they have been standardized, simplified, and stylized to make them easier to write, and their derivation is therefore not always obvious. Examples include 日 (rì) for "sun," 月 (yuè) for "moon," and 木 (mù) for "tree."

There is no concrete number for the proportion of modern characters that are pictographic in nature; however, Xu Shen (c. 100 C.E.) estimated that 4 percent of characters fell into this category.

2. Pictophonetic compounds (形聲字/形声字, Xíngshēngzì)

Also called semantic-phonetic compounds, or phono-semantic compounds, this category represents the largest group of characters in modern Chinese. Characters of this sort are composed of two parts: a pictograph, which suggests the general meaning of the character, and a phonetic part, which is derived from a character pronounced in the same way as the word the new character represents.

Examples are 河 (hé) river, 湖 (hú) lake, 流 (liú) stream, 冲 (chōng) riptide, 滑 (huá) slippery. All these characters have on the left a radical of three dots, which is a simplified pictograph for a water drop, indicating that the character has a semantic connection with water; the right-hand side in each case is a phonetic indicator. For example, in the case of 冲 (chōng), the phonetic indicator is 中 (zhōng), which by itself means middle. In this case it can be seen that the pronunciation of the character has diverged from that of its phonetic indicator; this process means that the composition of such characters can sometimes seem arbitrary today. Further, the choice of radicals may also seem arbitrary in some cases; for example, the radical of 貓 (māo) cat is 豸 (zhì), originally a pictograph for worms, but in characters of this sort indicating an animal of any sort.

Xu Shen (c. 100 C.E.) placed approximately 82 percent of characters into this category, while in the Kangxi Dictionary (1716 C.E.) the number is closer to 90 percent, due to the extremely productive use of this technique to extend the Chinese vocabulary.

3. Ideograph (指事字, zhǐshìzì)

Also called a simple indicative, simple ideograph, or ideogram, characters of this sort either add indicators to pictographs to make new meanings, or illustrate abstract concepts directly. For instance, while 刀 (dāo) is a pictogram for "knife," placing an indicator in the knife makes 刃 (rèn), an ideogram for "blade." Other common examples are 上 (shàng) for "up" and 下 (xià) for "down." This category is small, as most concepts can be represented by characters in other categories.

4. Logical aggregates (會意字/会意字, Huìyìzì)

Also translated as associative compounds, characters of this sort combine pictograms to symbolize an abstract concept. For instance, 木 (mu) is a pictogram of a tree, and putting two 木 together makes 林 (lin), meaning forest. Combining 日 (rì) sun and 月 (yuè) moon makes 明 (míng) bright, which is traditionally interpreted as symbolizing the combination of sun and moon as the natural sources of light.

Xu Shen estimated that 13 percent of characters fall into this category.

Some scholars flatly reject the existence of this category, opining that failure of modern attempts to identify a phonetic in an alleged logical aggregate is due simply to our not looking at ancient so-called secondary readings.[6] These are readings that were once common but have since been lost as the script evolved over time. Commonly given as a logical aggregate is ān 安 "peace" which is popularly said to be a combination of "building" 宀 and "woman" 女, together yielding something akin to "all is peaceful with the woman at home." However, 女 was in olden days most likely a polyphone with a secondary reading of *an, as may be gleaned from the set yàn 妟 "tranquil," nuán 奻 "to quarrel," jiān 姦 "licentious."

Adding weight to this argument is the fact that characters assigned to this "group" are almost invariably interpreted from modern forms rather than the archaic versions which, as a rule, are vastly different and often far more graphically complex. However, interpretations differ greatly, as can be evidenced from thorough studies of different sources.[7]

5. Associate transformation (轉注字/转注字, Zhuǎnzhùzì)

Characters in this category originally didn't represent the same meaning but have bifurcated through orthographic and often semantic drift. For instance, 考 (kǎo) to verify and 老 (lǎo) old were once the same character, meaning "elderly person," but detached into two separate words. Characters of this category are rare, so in modern systems this group is often omitted or combined with others.

6. Borrowing (假借字, Jiǎjièzì)

Also called phonetic loan characters, this category covers cases where an existing character is used to represent an unrelated word with similar pronunciation; sometimes the old meaning is then lost completely, as with characters such as 自 (zì), which has lost its original meaning of nose completely and exclusively means oneself, or 萬 (wan), which originally meant scorpion but is now used only in the sense of ten thousand.

This technique has become uncommon, since there is considerable resistance to changing the meaning of existing characters. However, it has been used in the development of written forms of dialects, notably Cantonese and Taiwanese in Hong Kong and Taiwan, due to the amount of dialectal vocabulary which historically has had no written form and thus lacks characters of its own.

Written Variants

Orthography

The nature of Chinese characters makes it very easy to produce allographs for any character, and there have been many efforts at orthographical standardization throughout history. The widespread usage of the characters in several different nations has prevented any one system becoming universally adopted; consequently, the standard shape of any given character in Chinese usage may differ subtly from its standard shape in Japanese or Korean usage, even where no simplification has taken place.

Usually, all Chinese characters take up the same amount of space, due to their block-like square nature. Beginners therefore typically practice writing with a grid as a guide. In addition to strictness in the amount of space a character takes up, Chinese characters are written with very precise rules. The three most important rules are the strokes employed, stroke placement, and the order in which they are written (stroke order). Most words can be written with just one stroke order, though some words also have variant stroke orders, which may occasionally result in different stroke counts; certain characters are also written with different stroke orders in different languages.

Common typefaces

There are two common typefaces based on the regular script for Chinese characters, akin to serif and sans-serif fonts in the West. The most popular for body text is a family of fonts called the Song typeface (宋体), also known as Minchō (明朝) in Japan, and Ming typeface (明體) in Taiwan and Hong Kong. The names of these fonts come from the Song and Ming dynasties, when block printing flourished in China. Because the wood grain on printing blocks ran horizontally, it was fairly easy to carve horizontal lines with the grain. However, carving vertical or slanted patterns was difficult because those patterns intersect with the grain and break easily. This resulted in a typeface that has thin horizontal strokes and thick vertical strokes. To prevent wear and tear, the ending of horizontal strokes are also thickened. These design forces elements in the current Song typeface characterized by thick vertical strokes contrasted with thin horizontal strokes; triangular ornaments at the end of single horizontal strokes; and overall geometrical regularity. This typeface is similar to Western serif fonts such as Times New Roman in both appearance and function.

The other common group of fonts is called the black typeface (黑体/體) in Chinese and Gothic typeface (ゴシック体) in Japanese. This group is characterized by straight lines of even thickness for each stroke, akin to sans-serif styles such as Arial and Helvetica in Western typography. This group of fonts, first introduced on newspaper headlines, is commonly used on headings, websites, signs and billboards.

Reforms: Simplification

Simplification in China

The use of traditional characters versus simplified characters varies greatly, and can depend on both the local customs and the medium. Because character simplifications were not officially sanctioned and generally a result of caoshu writing or idiosyncratic reductions, traditional, standard characters were mandatory in printed works, while the (unofficial) simplified characters would be used in everyday writing, or quick scribblings. Since the 1950s, and especially with the publication of the 1964 list, the Peoples Republic of China (PRC) has officially adopted a simplified script, while Hong Kong, Macau, and the Republic of China (ROC) retain the use of the traditional characters. There is no absolute rule for using either system, and often it is determined by the target audience, as well as the upbringing of the writer. In addition there is a special system of characters used for writing numerals in financial contexts; these characters are modifications or adaptations of the original, simple numerals, deliberately made complicated to prevent forgeries or unauthorized alterations.

Although most often associated with the PRC, character simplification predates the 1949 communist victory. Caoshu, cursive written text, almost always includes character simplification, and simplified forms have always existed in print, although not for the most formal works. In the 1930s and 1940s, discussions on character simplification took place within the Kuomintang government, and a large number of Chinese intellectuals and writers have long maintained that character simplification would help boost literacy in China. Indeed, this desire by the Kuomintang to simplify the Chinese writing system (inherited and implemented by the CCP) also nursed aspirations of some for the adoption of a phonetic script, in imitation of the Roman alphabet, and spawned such inventions as the Gwoyeu Romatzyh.

The PRC issued its first round of official character simplifications in two documents, the first in 1956 and the second in 1964. A second round of character simplifications (known as erjian, or "second round simplified characters") was promulgated in 1977. It was poorly received, and in 1986 the authorities rescinded the second round completely, while making six revisions to the 1964 list, including the restoration of three traditional characters that had been simplified: 叠 dié, 覆 fù, 像 xiàng.

Many of the simplifications adopted had been in use in informal contexts for a long time, as more convenient alternatives to their more complex standard forms. For example, the traditional character 來 lái (come) was written with the structure 来 in the clerical script (隸書 lìshū) of the Han dynasty. This clerical form uses two fewer strokes, and was thus adopted as a simplified form. The character 雲 yún (cloud) was written with the structure 云 in the oracle bone script of the Shāng dynasty, and had remained in use later as a phonetic loan in the meaning of to say. The simplified form reverted to this original structure.

Japanese kanji

In the years after World War II, the Japanese government also instituted a series of orthographic reforms. Some characters were given simplified forms called Shinjitai 新字体 (lit. "new character forms"; the older forms were then labeled the Kyūjitai 旧字体 , lit. "old character forms"). The number of characters in common use was restricted, and formal lists of characters to be learned during each grade of school were established, first the 1850-character Tōyō kanji 当用漢字 list in 1945, and later the 1945-character Jōyō kanji 常用漢字 list in 1981. Many variant forms of characters and obscure alternatives for common characters were officially discouraged. This was done with the goal of facilitating learning for children and simplifying kanji use in literature and periodicals. These are simply guidelines, hence many characters outside these standards are still widely known and commonly used, especially those used for personal and place names (for the former, see Jinmeiyō kanji).

Southeast Asian Chinese Communities

Singapore underwent three successive rounds of character simplification. These resulted in some simplifications that differed from those used in mainland China. It ultimately adopted the reforms of the PRC in their entirety as official, and has implemented them in the educational system.

Malaysia promulgated a set of simplified characters in 1981, which were also completely identical to the Mainland China simplifications; here, however, the simplifications were not generally widely adopted, as the Chinese educational system fell outside the purview of the federal government. However, with the advent of the PRC as an economic powerhouse, simplified characters are taught at school, and the simplified characters are more commonly, if not almost universally, used. However, a large majority of the older Chinese literate generation use the traditional characters. Chinese newspapers are published in either set of characters, with some even incorporating special Cantonese characters when publishing about the canto celebrity scene of Hong Kong.

| Traditional | Chinese simp. | Japanese simp. | meaning | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified in Chinese, not Japanese | 電 | 电 | 電 | electricity |

| 開 | 开 | 開 | open | |

| 東 | 东 | 東 | east | |

| 車 | 车 | 車 | car, vehicle | |

| 紅 | 红 | 紅 | red | |

| 無 | 无 | 無 | nothing | |

| 鳥 | 鸟 | 鳥 | bird | |

| 熱 | 热 | 熱 | hot | |

| Simplified in Japanese, not Chinese | 佛 | 佛 | 仏 | Buddha |

| 惠 | 惠 | 恵 | favor | |

| 拜 | 拜 | 拝 | kowtow, pray to, worship | |

| 黑 | 黑 | 黒 | black | |

| 冰 | 冰 | 氷 | ice | |

| 兔 | 兔 | 兎 | rabbit | |

| 姐 | 姐 | 姉 | older/elder sister | |

| 妒 | 妒 | 妬 | jealousy | |

| Simplified in both, but differently | 圖 | 图 | 図 | picture, diagram |

| 轉 | 转 | 転 | turn | |

| 廣 | 广 | 広 | wide, broad | |

| 惡 | 恶 | 悪 | bad, evil | |

| 綠 | 绿 | 緑 | green | |

| 腦 | 脑 | 脳 | brain | |

| 樂 | 乐 | 楽 | fun | |

| 氣 | 气 | 気 | air | |

| Simplified in both in the same way | 學 | 学 | 学 | learn |

| 體 | 体 | 体 | body | |

| 點 | 点 | 点 | dot, point | |

| 貓 | 猫 | 猫 | cat | |

| 蟲 | 虫 | 虫 | insect | |

| 黃 | 黄 | 黄 | yellow | |

| 盜 | 盗 | 盗 | thief | |

| 國 | 国 | 国 | country |

Note: this table is merely a brief sample, not a complete listing.

Dictionaries

Dozens of indexing schemes have been created for arranging Chinese characters in Chinese dictionaries. The great majority of these schemes have appeared in only a single dictionary; only one such system has achieved truly widespread use. This is the system of radicals. There are 214 radicals in the Chinese written language.

Chinese character dictionaries often allow users to locate entries in several different ways. Many Chinese, Japanese, and Korean dictionaries of Chinese characters list characters in radical order: characters are grouped together by radical, and radicals containing fewer strokes come before radicals containing more strokes. Under each radical, characters are listed by their total number of strokes. It is often also possible to search for characters by sound, using pinyin (in Chinese dictionaries), zhuyin (in Taiwanese dictionaries), kana (in Japanese dictionaries) or hangul (in Korean dictionaries). Most dictionaries also allow searches by total number of strokes, and individual dictionaries often allow other search methods as well.

For instance, to look up the character where the sound is not known, e.g., 松 (pine tree), the user first determines which part of the character is the radical (here 木), then counts the number of strokes in the radical (four), and turns to the radical index (usually located on the inside front or back cover of the dictionary). Under the number "4" for radical stroke count, the user locates 木, then turns to the page number listed, which is the start of the listing of all the characters containing this radical. This page will have a sub-index giving remainder stroke numbers (for the non-radical portions of characters) and page numbers. The right half of the character also contains four strokes, so the user locates the number 4, and turns to the page number given. From there, the user must scan the entries to locate the character he or she is seeking. Some dictionaries have a sub-index which lists every character containing each radical, and if the user knows the number of strokes in the non-radical portion of the character, he or she can locate the correct page directly.

Another dictionary system is the four corner method, where characters are classified according to the "shape" of each of the four corners.

Most modern Chinese dictionaries and Chinese dictionaries sold to English speakers use the traditional radical-based character index in a section at the front, while the main body of the dictionary arranges the main character entries alphabetically according to their pinyin spelling. To find a character with unknown sound using one of these dictionaries, the reader finds the radical and stroke number of the character, as before, and locates the character in the radical index. The character's entry will have the character's pronunciation in pinyin written down; the reader then turns to the main dictionary section and looks up the pinyin spelling alphabetically.

Sinoxenic languages

Besides Japanese and Korean, a number of Asian languages have historically been written using Han characters, with characters modified from Han characters, or using Han characters in combination with native characters. They include:

- Iu Mien language

- Jurchen language

- Khitan language

- Miao language

- Nakhi (Naxi) language (Geba script)

- Tangut language

- Vietnamese language (Chữ nôm)

- Zhuang language (using Zhuang logograms, or "sawndip")

In addition, the Yi script is similar to Han, but is not known to be directly related to it.

Number of Chinese Characters

The total number of Chinese characters from past to present remains unknowable because new ones are developed all the time. Chinese characters are theoretically an open set. The number of entries in major Chinese dictionaries is the best means of estimating the historical growth of character inventory.

| Year | Name of dictionary | Number of characters |

|---|---|---|

| 100 | Shuowen Jiezi | 9,353 |

| 543? | Yupian | 12,158 |

| 601 | Qieyun | 16,917 |

| 1011 | Guangyun | 26,194 |

| 1039 | Jiyun | 53,525 |

| 1615 | Zihui | 33,179 |

| 1716 | Kangxi Zidian | 47,035 |

| 1916 | Zhonghua Da Zidian | 48,000 |

| 1989 | Hanyu Da Zidian | 54,678 |

| 1994 | Zhonghua Zihai | 85,568 |

A comparison of the Shuowen Jiezi with Hanyu Da Zidian reveals that the overall number of characters has increased 577 percent over 1,900 years. Depending upon how one counts variants, 50,000+ is a good approximation for the current total number. This correlates with the most comprehensive Japanese and Korean dictionaries of Chinese characters; the Dai Kan-Wa Jiten has some 50,000 entries, and the Han-Han Dae Sajeon has over 57,000. The latest behemoth, the Zhonghua Zihai, records a staggering 85,568 single characters, although even this fails to list all characters known, ignoring the roughly 1,500 Japanese-made kokuji given in the Kokuji no Jiten as well as the Chu Nom inventory only used in Vietnam in past days.

Modified radicals and obsolete variants are two common reasons for the ever-increasing number of characters. Creating a new character by modifying the radical is an easy way to disambiguate homographs among xíngshēngzì pictophonetic compounds. This practice began long before the standardization of Chinese script by Qin Shi Huang and continues to the present day. The traditional 3rd-person pronoun tā (他 "he; she; it"), which is written with the "person radical," illustrates modifying significs to form new characters. In modern usage, there is a graphic distinction between tā (她 "she") with the "woman radical," tā (牠 "it") with the "animal radical," tā (它 "it") with the "roof radical," and tā (祂 "He") with the "deity radical," One consequence of modifying radicals is the fossilization of rare and obscure variant logographs, some of which are not even used in Classical Chinese. For instance, he 和 "harmony; peace," which combines the "grain radical" with the "mouth radical," has infrequent variants 咊 with the radicals reversed and 龢 with the "flute radical."

Chinese

It is usually said that about 3,000 characters are needed for basic literacy in Chinese (for example, to read a Chinese newspaper), and a well-educated person will know well in excess of 4,000 to 5,000 characters. Note that Chinese characters should not be confused with Chinese words, as the majority of modern Chinese words, unlike their Ancient Chinese and Middle Chinese counterparts, are multi-morphemic and multi-syllabic compounds, that is, most Chinese words are written with two or more characters; each character representing one syllable. Knowing the meanings of the individual characters of a word will often allow the general meaning of the word to be inferred, but this is not invariably the case.

In the People's Republic of China, which uses Simplified Chinese characters, the Xiàndài Hànyǔ Chángyòng Zìbiǎo (现代汉语常用字表; Chart of Common Characters of Modern Chinese) lists 2,500 common characters and 1,000 less-than-common characters, while the Xiàndài Hànyǔ Tōngyòng Zìbiǎo (现代汉语通用字表; Chart of Generally Utilized Characters of Modern Chinese) lists 7,000 characters, including the 3,500 characters already listed above. GB2312, an early version of the national encoding standard used in the People's Republic of China, has 6,763 code points. GB18030, the modern, mandatory standard, has a much higher number. The Hànyǔ Shuǐpíng Kǎoshì proficiency test covers approximately 5,000 characters.

In the ROC, which uses Traditional Chinese characters, the Ministry of Education's Chángyòng Guózì Biāozhǔn Zìtǐ Biǎo (常用國字標準字體表; Chart of Standard Forms of Common National Characters) lists 4,808 characters; the Cì Chángyòng Guózì Biāozhǔn Zìtǐ Biǎo (次常用國字標準字體表; Chart of Standard Forms of Less-Than-Common National Characters) lists another 6,341 characters. The Chinese Standard Interchange Code (CNS11643)—the official national encoding standard—supports 48,027 characters, while the most widely-used encoding scheme, BIG-5, supports only 13,053.

In Hong Kong, which uses Traditional Chinese characters, the Education and Manpower Bureau's Soengjung Zi Zijing Biu (常用字字形表), intended for use in elementary and junior secondary education, lists a total of 4,759 characters.

In addition, there is a large corpus of dialect characters, which are not used in formal written Chinese but represent colloquial terms in non-Mandarin Chinese spoken forms. One such variety is Written Cantonese, in widespread use in Hong Kong even for certain formal documents, due to the former British colonial administration's recognition of Cantonese for use for official purposes. In Taiwan, there is also an informal body of characters used to represent the spoken Hokkien (Min Nan) dialect.

Japanese

In Japanese there are 1945 Jōyō kanji (常用漢字 lit. "frequently used kanji") designated by the Japanese Ministry of Education; these are taught during primary and secondary school. The list is a recommendation, not a restriction, and many characters missing from it are still in common use.

The one area where character usage is officially restricted is in names, which may contain only government-approved characters. Since the Jōyō kanji list excludes many characters which have been used in personal and place names for generations, an additional list, referred to as the Jinmeiyō kanji (人名用漢字 lit. "kanji for use in personal names"), is published. It currently contains 983 characters, bringing the total number of government-endorsed characters to 2928. (See also the Names section of the Kanji article.)

Today, a well-educated Japanese person may know upwards of 3500 kanji. The Kanji kentei (日本漢字能力検定試験 Nihon Kanji Nōryoku Kentei Shiken or Test of Japanese Kanji Aptitude) tests a speaker's ability to read and write kanji. The highest level of the Kanji kentei tests on 6000 kanji, though in practice few people attain or need this level.

Korean

In times past, until the fifteenth century, in Korea, Chinese was the only form of written communication, prior to the creation of Hangul, the Korean alphabet. Much of the vocabulary, especially in the realms of science and sociology, comes directly from Chinese. However, due the lack of tones in Korean, as the words were imported from Chinese, many dissimilar characters took on identical sounds, and subsequently identical spelling in Hangul. Chinese characters are sometimes used to this day for either clarification in a practical manner, or to give a distinguished appearance, as knowledge of Chinese characters is considered a high class attribute and an indispensable part of a classical education.

In Korea, 한자 Hanja have become a politically contentious issue, with some Koreans urging a "purification" of the national language and culture by totally abandoning their use. These individuals encourage the exclusive use of the native Hangul alphabet throughout Korean society and the end to character education in public schools. On the other hand, some Korean scholars have made the controversial claim that since the dominant people of the Shang Dynasty were Koreans, Chinese characters were "probably invented and developed by Koreans."[8]

In South Korea, educational policy on characters has swung back and forth, often swayed by education ministers' personal opinions. At times, middle and high school students have been formally exposed to 1,800 to 2,000 basic characters, albeit with the principal focus on recognition, with the aim of achieving newspaper-literacy. Since there is little need to use Hanja in everyday life, young adult Koreans are often unable to read more than a few hundred characters.

There is a clear trend toward the exclusive use of Hangul in day-to-day South Korean society. Hanja are still used to some extent, particularly in newspapers, weddings, place names and calligraphy. Hanja is also extensively used in situations where ambiguity must be avoided, such as academic papers, high-level corporate reports, government documents, and newspapers; this is due to the large number of homonyms that have resulted from extended borrowing of Chinese words.

The issue of ambiguity is the main hurdle in any effort to "cleanse" the Korean language of Chinese characters. Characters convey meaning visually, while alphabets convey guidance to pronunciation, which in turn hints at meaning. As an example, in Korean dictionaries, the phonetic entry for 기사 gisa yields more than 30 different entries. In the past, this ambiguity had been efficiently resolved by parenthetically displaying the associated hanja.

In the modern Korean writing system based on Hangul, Chinese characters are not used any more to represent native morphemes.

In North Korea, the government, wielding much tighter control than its sister government to the south, has banned Chinese characters from virtually all public displays and media, and mandated the use of Hangul in their place.

Vietnamese

Although now nearly extinct in Vietnamese, varying scripts of Chinese characters (hán tự) were once in widespread use to write the language, although hán tự became limited to ceremonial uses beginning in the nineteenth century. Similarly to Japan and Korea, Chinese (especially Classical Chinese) was used by the ruling classes, and the characters were eventually adopted to write Vietnamese. To express native Vietnamese words which had different pronunciations from the Chinese, Vietnamese developed the Chu Nom script which used various methods to distinguish native Vietnamese words from Chinese. Vietnamese is currently exclusively written in the Vietnamese alphabet, a derivative of the Latin alphabet.

Rare and Complex Characters

Often a character not commonly used (a "rare" or "variant" character) will appear in a personal or place name in Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese (see Chinese name, Japanese name, Korean name, and Vietnamese name, respectively). This has caused problems as many computer encoding systems include only the most common characters and exclude the less oft-used characters. This is especially a problem for personal names which often contain rare or classical, antiquated characters.

People who have run into this problem include Taiwanese politicians Wang Chien-shien (王建煊, pinyin Wáng Jiànxuān) and Yu Shyi-kun (游錫堃, pinyin Yóu Xīkūn), ex-PRC Premier Zhu Rongji (朱镕基 Zhū Róngjī), and Taiwanese singer David Tao (陶喆 Táo Zhé). Newspapers have dealt with this problem in varying ways, including using software to combine two existing, similar characters, including a picture of the personality, or, especially as is the case with Yu Shyi-kun, simply substituting a homophone for the rare character in the hope that the reader would be able to make the correct inference. Japanese newspapers may render such names and words in katakana instead of kanji, and it is accepted practice for people to write names for which they are unsure of the correct kanji in katakana instead.

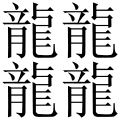

There are also some extremely complex characters which have understandably become rather rare. According to Bellassen,[9] the most complex Chinese character is zhé (pictured right, top), meaning "verbose" and boasting sixty-four strokes; this character fell from use around the fifth century. It might be argued, however, that while boasting the most strokes, it is not necessarily the most complex character (in terms of difficulty), as it simply requires writing the same sixteen-stroke character 龍 lóng (lit. "dragon") four times in the space for one.

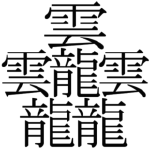

The most complex character found in modern Chinese dictionaries is 齉 nàng (pictured right, middle), meaning "snuffle" (that is, a pronunciation marred by a blocked nose), with "just" thirty-six strokes. The most complex character that can be input using the Microsoft New Phonetic IMA 2002a for Traditional Chinese is 龘 tà "the appearance of a dragon in flight"; it is composed of the dragon radical represented three times, for a total of 16 × 3 = 48.

In Japanese, an 84-stroke kokuji exists—it is composed of three "cloud" (雲) characters on top of the abovementioned triple "dragon" character (龘). Also meaning "the appearance of a dragon in flight," it is pronounced おとど otodo, たいと taito, and だいと daito.

The most complex Chinese character still in use may be biáng (pictured right, bottom), with 57 strokes, which refers to Biang biang noodles, a type of noodle from China's Shaanxi province. This character along with syllable biang cannot be found in dictionaries. The fact that it represents a syllable that does not exist in any Standard Mandarin word means that it could be classified as a dialectal character.

In contrast, the simplest character is 一 yī ("one") with just one horizontal stroke. The most common character in Chinese is 的 de, a grammatical particle functioning as an adjectival marker and as a clitic genitive case analogous to the English ’s, with eight strokes. The average number of strokes in a character has been calculated as 9.8;[9] it is unclear, however, whether this average is weighted, or whether it includes traditional characters.

Another very simple Chinese logograph is the character 〇 (líng), which simply refers to the number zero. For instance, the year 2000 would be 二〇〇〇年. However, there is another way to write zero which would be 零. The logograph 〇 is a native Chinese character, and its earliest documented use is in 1247 C.E. during the Southern Song dynasty period, found in a mathematical text called 數術九章 (Shǔ Shù Jiǔ Zhāng "Mathematical Treatise in Nine Sections"). It is not directly derived from the Hindi-Arabic numeral "0".[10] Interestingly, being round, the character does not contain any traditional strokes.

Chinese Calligraphy

The art of writing Chinese characters is called Chinese calligraphy. It is usually done with ink brushes. In ancient China, Chinese calligraphy was one of the Four Arts of the Chinese Scholars. Traditionally, scholars and imperial bureaucrats kept the Four Treasures necessary for calligraphy in their studies: brush, paper, an ink stick and an inkstone on which the ink stick was rubbed and mixed with water to produce ink.

Calligraphy is considered a fine art in Asia, along with landscape painting and the writing of poetry. Often a calligraphic poem was included in a landscape to add meaning to the scene. Calligraphy is appreciated for its aesthetic beauty, but also as an expression of the inner nature of the calligrapher who creates it.

There is a minimalist set of rules of Chinese calligraphy. Every character from the Chinese scripts is built into a uniform shape by means of assigning it a geometric area in which the character must occur. Each character has a set number of brushstrokes, none must be added or taken away from the character to enhance it visually, lest the meaning be lost. Finally, strict regularity is not required, meaning the strokes may be accentuated for dramatic effect of individual style. Calligraphy was the means by which scholars could record their thoughts and teachings for immortality. Works of calligraphy are among the precious treasures that are still in existence from ancient China.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Jerry Norman, Chinese (Cambridge University Press, 1988, ISBN 978-0521296533).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 William G. Boltz, Early Chinese Writing World Archaeology 17(3) (Feb. 1986): 420-436. Retrieved November 14, 2023.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 David N. Keightley, Art, Ancestors, and the Origins of Writing in China Representations 56, Special Issue: The New Erudition (Autumn, 1996): 68-95.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 John DeFrancis, Chinese Visible Speech: The Diverse Oneness of Writing Systems. Retrieved November 14, 2023.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Paul Rincon, 'Earliest writing' found in China, BBC Science (April 17, 2003). Retrieved November 14, 2023.

- ↑ William G. Boltz, The Origin and Early Development of the Chinese Writing System (New Haven, CT: American Oriental Society, 1993, ISBN 0940490188), 104-110.

- ↑ Philip Philipsen, Sound Business: The Reality of Chinese Characters (iUniverse, Inc., 2005, ISBN 059535629X), 49-76.

- ↑ Nam Hyun-woo, Chinese character's origin questioned The Korea Times (August 21, 2015). Retrieved November 14, 2023.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Joël Bellassen and Zhang Pengpeng, Méthode d'Initiation à la Langue et à l'Écriture chinoises (La Compagnie, 1990, ISBN 295041351X) (in French)

- ↑ Joseph Needham, Science and Civilization in China, Volume III (Cambridge, UK: University Press, 1954, ISBN 9780521087322).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bellassen, Joël, and Pʻeng-pʻeng Chang. Méthode d'initiation à la langue et à l'écriture chinoises. Paris: La Compagnie, 1990. ISBN 295041351X

- Boltz, William G. The origin and the development of the Chinese writing system. (American Oriental series), v. 78. New Haven, CT: American Oriental Society, 1993. ISBN 0940490188

- Chen, Lingchei Letty. Writing Chinese: reshaping Chinese cultural identity. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. ISBN 1403971293

- Needham, Joseph, and Ling Wang. Science and civilization in China. Cambridge, UK: University Press, 1954. ISBN 9780521087322

- Norman, Jerry. Chinese. (Cambridge language surveys.) Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1988. ISBN 9780521296533

- Philipsen, Philip. Sound Business: The Reality of Chinese Characters. iUniverse, Inc. 2005. ISBN 059535629X

- Qiu, Xigui, Gilbert Louis Mattos, and Jerry Norman. Chinese writing. Early China special monograph series, no. 4. Berkeley, CA: Society for the Study of Early China and the Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, 2000. ISBN 1557290717

External links

All links retrieved December 10, 2023.

- History of Chinese writing Pinyin.Info.

- Unihan Database: Chinese, Japanese, and Korean references, readings, and meanings for all the Chinese and Chinese-derived characters in the Unicode character set.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.