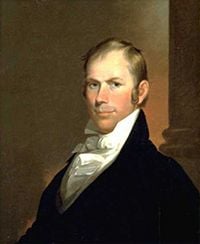

Henry Clay

| Henry Clay | |

| |

9th United States Secretary of State

| |

| In office March 7, 1825 â March 3, 1829 | |

| Under President | John Quincy Adams |

|---|---|

| Preceded by | John Quincy Adams |

| Succeeded by | Martin Van Buren |

8th Speaker of the United States House of Representatives

| |

| In office November 4, 1811 â January 19, 1814 | |

| Preceded by | Joseph Bradley Varnum |

| Succeeded by | Langdon Cheves |

10th Speaker of the United States House of Representatives

| |

| In office December 4, 1815 â October 28, 1820 | |

| Preceded by | Langdon Cheves |

| Succeeded by | John W. Taylor |

13th Speaker of the United States House of Representatives

| |

| In office December 1, 1823 â March 4, 1825 | |

| Preceded by | Philip Pendleton Barbour |

| Succeeded by | John W. Taylor |

| Born | April 4, 1777 Hanover County, Virginia |

| Died | June 29, 1777 Washington, D.C. |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican, National Republican, Whig |

| Spouse | Lucretia Hart |

| Profession | Politician, Lawyer |

| Religion | Episcopal |

Henry Clay (April 12, 1777 â June 29, 1852) was a leading American statesman and orator who represented Kentucky in both the House of Representatives and Senate. With his influential contemporaries Daniel Webster and John Calhoun, Clay, sought to consolidate and secure democratic representative government inherited from the founding generation. Major issues concerning the distribution of power between branches of government and between states and the federal government; the balance between governmental authority and individual liberty; and economic and foreign policy were debated and important precedents set during Clay's long tenure in the U.S. Congress.

While never rising to the presidency, Clay became perhaps the most influential congressional leader in American history. He served as Speaker of the House longer than any man in the nineteenth century, elevating the office into one of enormous power. Clay's influence arguably exceeded that of any president of his era, excepting Andrew Jackson.

Known as "The Great Compromiser," Clay was the founder and leader of the Whig Party and principal backer of the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which attempted to resolve the issue of slavery in the new territories. The great issues of slavery, states rights, and regional distribution of power were acerbated by the westward expansion following the Mexican War, leading ultimately to the American Civil War. When the war did come, Kentucky chose to remain within the Union, despite being a slave state, doubtless following the path Clay would have taken.

Clay's American System advocated a robust federal role that included programs for modernizing the economy, tariffs to protect industry, a national bank, and internal improvements to build canals, ports and railroads. He saw the United States not as a group of independent states but as one nation best served by a strong central government.

Clay's political philosophy and stance toward the defining issue of the era, slavery, would profoundly influence fellow Kentuckian Abraham Lincoln. Clay despised slavery, yet sought its gradual eradication, treasured the Union above all, and supported the vigorous use of federal power to answer the national interestsâall positions that would incline Lincoln to respond with force when seven Southern states adopted articles of secession following Lincoln's election as president in 1860.

Early Life

Henry Clay was born on April 12, 1777, in Hanover County, Virginia, the seventh of nine children of the Reverend John Clay and Elizabeth Hudson Clay. His father, a Baptist minister, died four years later in 1781, leaving Henry and his brothers two slaves each, and his wife 18 slaves and 464 acres of land.

Ten years later his mother remarried and his stepfather, Capt. Henry Watkins, moved the family to Richmond, where Clay worked first as a store clerk and from 1793 to 1797, as secretary to George Wythe, the chancellor of the Commonwealth of Virginia, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, and the first professor of law in the United States. Wythe took an active interest in Clay's future and arranged a position for him with the Virginia attorney general, Robert Brooke.

Clay studied law under Wythe and was was admitted to the bar in 1797, and in November of that year moved to Lexington, Kentucky. In 1799 he married Lucretia Hart, of a leading family in the community, and was the father of 11 children.

Clay soon established a reputation for his legal skills and courtroom oratory. In 1803, as a representative of Fayette County in the Kentucky General Assembly, Clay focused his attention mostly on trying to move the State capital from Frankfort to Lexington. In 1806, United States District Attorney Joseph Hamilton Daviess indicted former vice president Aaron Burr for planning a military expedition into Spanish Territory west of the Mississippi River, and Clay and John Allen successfully defended Burr.

On January 3, 1809, Clay introduced to the Kentucky General Assembly a resolution requiring members to wear homespun suits rather than imported British broadcloth. Only two members voted against the patriotic measure. One of them, Humphrey Marshall, had been hostile toward Clay during the trial of Aaron Burr, and after the two nearly came to blows on the Assembly floor, Clay challenged Marshall to a duel. The duel took place on January 9 in Shippingport, Indiana. They each had three turns, and Clay grazed Marshall once just below the chest, while Marshall hit Clay once in the thigh.

Speaker of the House

In 1812, at the age of 34, Henry Clay was elected to the United States House of Representatives and in a remarkable tribute to his reputation as a leader, was chosen Speaker of the House on the first day of the session. During the next 14 years, he was re-elected five times both to the House and to the speakership.

Before Clay's entrance into the House, the position of Speaker had been that of a rule enforcer and mediator. Clay turned the speakership into a position of power second only to the president. He immediately appointed members of the War Hawk faction to all the important committees, gaining effective control of the House.

As the Congressional leader of the Democratic-Republican Party, Clay took charge of the agenda, especially as a "War Hawk," supporting the War of 1812 with the British Empire. Later, as one of the peace commissioners, Clay helped negotiate the Treaty of Ghent and signed it on December 24, 1814. In 1815, while still in Europe, he helped negotiate a commerce treaty with Great Britain.

Clay's tenure as Speaker of the House shaped the history of Congress. Evidence from committee assignment and roll call records shows that Clay's leadership strategy was highly complex and that it advanced his public policy goals as well as his political ambition.

Clay sympathized with the plight of free blacks. Believing that "unconquerable prejudice resulting from their color, they never could amalgamate with the free whites of this country, "Clay supported the program of the American Colonization Society, a group that wanted to send freed slaves to Africa, specifically Monrovia in Liberia.

The American System

After the war Clay and John C. Calhoun helped to pass the Tariff of 1816 as part of the national economic plan Clay called "The American System." This system was based on the economic principles of Alexander Hamilton, advanced in his influential "Report on Manufactures" as treasury secretary in the administration of George Washington. The American System was designed to allow the fledgling American manufacturing sector, largely centered on the eastern seaboard, to compete with British manufacturing. After the conclusion of the War of 1812, British factories were overwhelming American ports with inexpensive goods. To persuade voters in the western states to support the tariff, Clay advocated federal government support for internal improvements to infrastructure, principally roads and canals. These projects would be financed by the tariff and by sale of the public lands, prices for which would be kept high to generate revenue. Finally, a national bank would stabilize the currency and serve as the nexus of a truly national financial system.

The American System was supported by both the North and the South at first. However, it affected the South negatively because other countries retaliated by raising tariffs on U.S. exports. This disproportionally hurt the South because its economy was based on agricultural exports. When the additional Tariff of 1828 was requested, the South broke away from their support leading to the Nullification Crisis. The increasing sectionalism between North and South (and to some extent between east and west) was to continually worsen in the decades leading up to the American Civil War.

The Missouri Compromise and 1820s

In 1820 a dispute erupted over the extension of slavery in Missouri Territory. Clay helped settle this dispute by gaining Congressional approval for a plan that was called the "Missouri Compromise." It brought in Maine as a free state and Missouri as a slave state, thus maintaining the balance in the Senate, which had been 11 free and 11 slave states. The compromise also forbade slavery north of 36-30 (the northern boundary of Arkansas), with the exception of Missouri.

In national terms the old Republican Party caucus had ceased to function by 1820. Clay ran for president in 1824 and came in fourth place. He threw his support to John Quincy Adams, who won despite having trailed Andrew Jackson in both the popular and electoral votes. Adams then appointed Clay as Secretary of State in what Jackson partisans termed "the corrupt bargain." Clay used his influence to build a national network of supporters, called National Republicans.

Jackson, outmaneuvered for the presidency in 1824, combined with Martin Van Buren to form a coalition that defeated Adams in 1828. That new coalition became a full-fledged party that by 1834 called itself Democrats. By 1832 Clay had merged the National Republicans with other factions to form the Whig party.

In domestic policy Clay promoted the American System, with a high tariff to encourage manufacturing, and an extensive program of internal improvements to build up the domestic market. After a long fight he did get a high tariff in 1828 but did not get the spending for internal improvements. In 1822 Monroe vetoed a bill to build the Cumberland Road crossing the Allegheny Mountains.

In foreign policy, Clay was the leading American supporter of the independence movements and revolutions in Latin America after 1817. Between 1821 and 1826 the U.S. recognized all the new countries, except Uruguay (whose independence was debated and recognized only later). When in 1826 the U.S. was invited to attend the Columbia Conference of new nations, opposition emerged, and the U.S. delegation never arrived. Clay also supported the Greek independence revolutionaries in 1824 who wished to separate from the Ottoman Empire, an early move into European affairs.

The Nullification Crisis

After the passage of the Tariff Act of 1828, which raised tariffs considerably in an attempt to protect fledgling factories built under previous tariff legislation, South Carolina attempted to nullify U.S. tariff laws. It threatened to secede from the Union if the United States government tried to enforce the tariff laws. Furious, President Andrew Jackson threatened in return to go to South Carolina and hang any man who refused to obey the law.

The crisis worsened until 1833 when Clay helped to broker a deal to gradually lower the tariff. This measure helped to preserve the supremacy of the federal government over the states and would be only one precursor to the developing conflict between the northern and southern United States over economics and slavery.

Candidate for president

Clay ran for president five times during his political career but was never won election to the nation's highest office. In 1824 Clay ran as a Democratic-Republican in a field that included John Quincy Adams, Andrew Jackson, and William H. Crawford. There was no clear majority in the Electoral College, and the election was thrown to the U.S. House of Representatives. As per the Twelfth Amendment, only the top three candidates in the electoral vote were candidates in the House, which excluded Clay, but as Speaker of the House, would play a crucial role in deciding the presidency. Clay detested Jackson and had said of him, âI cannot believe that killing 2,500 Englishmen at New Orleans qualifies for the various, difficult, and complicated duties of the Chief Magistracy.â Moreover, Clay's American System was far closer to Adams' position on tariffs and internal improvements than Jackson's or Crawford's. Clay accordingly threw his support to John Quincy Adams, who was elected president on February 9, 1825, on the first ballot.

Adams' victory shocked Jackson, who expected that, as the winner of a plurality of both the popular and electoral votes, he should have been elected President. When President Adams appointed Clay his secretary of state, essentially declaring him heir to the presidencyâAdams and his three predecessors as president had all served as secretary of stateâJackson and his followers accused Adams and Clay of striking a âcorrupt bargain.â The Jacksonians would campaign on this claim for the next four years, ultimately leading to Jackson's victory in the Adams-Jackson rematch in 1828. Clay denied this and no evidence has been found to support this claim.

In 1832 Clay was unanimously nominated for the presidency by the National Republicans to face Jackson. The main issue was the policy of continuing the Second Bank of the United States and Clay lost by a wide margin to the highly popular Jackson (55 percent to 37 percent).

In 1840, Clay again ran as a candidate for the Whig nomination but he was defeated in the party convention by supporters of war hero William Henry Harrison to face President Martin van Buren, Jackson's vice president. Harrison won the election, but died in office within weeks, after contracting pneumonia during his long inaugural address in January 1841.

Clay was again nominated by the Whigs in 1844 and ran in the general election against James K. Polk, the Democratic candidate. Clay lost due in part to national sentiment for Polk's program "54Âş 40' or Fight" campaign to settle the northern boundary of the United States with Canada then under the control of the British Empire. Clay also opposed admitting Texas as a state because he felt it would reawaken the Slavery issue and provoke Mexico to declare war. Polk took the opposite view and public sentiment was with him, especially in the southern United States. Nevertheless, the election was close; New York's 36 electoral votes proved the difference, and went to Polk by a slim 5,000 vote margin. Liberty Party candidate James G. Birney won a little over 15,000 votes in New York and may have taken votes from Clay.

Clay's warnings came true as annexation of Texas led to the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), while the North and South came to heads over the extending slavery into Texas and beyond during Polk's presidency. In 1848, Zachary Taylor, a Mexican-American War hero, won the Whig nomination, again depriving Clay of the nomination.

Henry Clay's presidential bids were lost by wide margins, representing in his earlier presidential bids a failure to form a national coalition and a lack of political organization that could match the Jacksonian Democrats. And although the Whigs had become as adept at political organizing as the Democrats by the time of Clay's final presidential bid, Clay himself failed to connect to the people, partly due to his unpopular views on slavery and the American System in the South. When Clay was warned not to take a stance against slavery or be so strong for the American System, he was quoted as saying in return, "I'd rather be right than be President!"

The Compromise of 1850

After losing the Whig Party nomination to Zachary Taylor in 1848, Clay retired to his Ashland estate in Kentucky before again being in 1849 elected to the U.S. Senate. During his term northern and southern states were again wrangling over slavery extension, as Clay had predicted they would, this time over the admission or exclusion of slavery in the territories recently acquired from Mexico.

Always the "Great Compromiser," Clay helped work out what historians have called the Compromise of 1850. This plan allowed slavery in the New Mexico and Utah territories while admitting California to the Union as a free state. It also included a new Fugitive Slave Act and banned the slave trade (but not slavery itself) in the District of Columbia. This compromise delayed the outbreak of the American Civil War for an additional eleven years.

Clay continued to serve both the Union he loved and his home state of Kentucky until June 29, 1852 when he passed away in Washington, DC, at the age of 75. Clay was the first person to lie in state in the United States Capitol. He was buried in Lexington Cemetery. His headstone reads simply: "I know no North-no South-no East-no West."

Religion

Although Henry Clayâs father was a Baptist preacher, Henry Clay himself really belonged to no church until he was baptized into the Episcopalian church in 1847.

Legacy

Henry Clay was arguably the most influential congressional leader in American history. Clay's American System, with its robust federal role, distanced the American experiment from the Jeffersonian ideal of a largely agricultural society with highly constrained federal powers. Clay saw the United States not as a group of independent states but as one nation best served by a strong central government. "It has been my invariable rule to do all for the Union," he stated in 1844. "If any man wants the key to my heart, let him take the key of the Union, and that is the key to my heart."

Clay's views on slavery were progressive for his time, although appearing in hindsight to be contradictory and hypocritical. He always condemned slavery as a great evil, a curse on both the slave and the master, and a stain on the reputation of the country. He even tried to outlaw slavery in his home state of Kentucky. Yet he owned up to 60 slaves, and as the president of the American Colonization Society thought the social integration of emancipated blacks was virtually impossible and favored returning slaves to Africa as the most realistic solution. He was known for his kind treatment of his slaves and emancipated most of them before he died.

Clay profoundly influenced his fellow Kentuckian Abraham Lincoln. Like Clay, Lincoln was a Whig who favored a strong central government, treasured the Union above all, and despised slavery as a degrading institution, yet sought gradual measures that would lead to its eradication. When southern states passed ordinances of secession following Lincoln's election as president in 1860, Lincoln's dedication to the Union and predisposition to marshal the power of the federal government to meet national exigencies led to a forceful military response and the outbreak of the transforming Civil War, which not only eradicated slavery but established a much more dominant role of the federal government in American life.

Lincoln's eulogy of Clay, whom he termed his "beau ideal of a statesman," on the day after his death stresses Clay's devotion to liberty and praises him as a man "the times have demanded":

Mr. Clay's predominant sentiment, from first to last, was a deep devotion to the cause of human libertyâa strong sympathy with the oppressed everywhere, and an ardent wish for their elevation. With him, this was a primary and all controlling passion. Subsidiary to this was the conduct of his whole life. He loved his country partly because it was his own country, but mostly because it was a free country; and he burned with a zeal for its advancement, prosperity and glory, because he saw in such, the advancement, prosperity and glory, of human liberty, human right and human nature. He desired the prosperity of his countrymen partly because they were his countrymen, but chiefly to show to the world that freemen could be prosperous.

In 1957 a Senate committee led by John F. Kennedy and charged with honoring its most distinguished past members named Henry Clay the greatest member of Congress in the country's history. Henry Clay's Lexington farm and mansion, Ashland, is now a museum and is open to the public.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Baxter, Maurice G. Henry Clay the lawyer. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2000. ISBN 9780813121475

- Clay, Henry, James F. Hopkins, and Robert Seager. Papers. [Lexington]: University of Kentucky Press, 1959. ISBN 9780813100562

- Remini, Robert Vincent. Henry Clay: statesman for the Union. New York: W.W. Norton 1991. ISBN 9780393030044

- Shankman, Kimberly C. Compromise and the Constitution: the political thought of Henry Clay. Lanham, Md: Lexington Books, 1999. ISBN 9780739100363

- Watson, Harry L. Andrew Jackson vs. Henry Clay: democracy and development in antebellum America. (The Bedford series in history and culture.) Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's 1998. ISBN 9780312177720

External links

All links retrieved June 25, 2024.

| |||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.