James K. Polk

| Term of office | March 4, 1845 – March 3, 1849 |

| Preceded by | John Tyler |

| Succeeded by | Zachary Taylor |

| Date of birth | November 2, 1795 |

| Place of birth | Mecklenburg County, North Carolina |

| Date of death | June 15, 1849 |

| Place of death | Nashville, Tennessee |

| Spouse | Sarah Childress Polk |

| Political party | Democratic |

James Knox Polk (November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) was the eleventh President of the United States, serving from March 4, 1845, to March 3, 1849. Born in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, Polk lived most of his life in Tennessee. The last of the Jacksonian Democrats to achieve high office, Polk served as Speaker of the United States House of Representatives (1835–1839) and governor of Tennessee (1839–1841) before becoming president. He is noted for his success in winning the war with Mexico and adding vast new territories to the young United States. He raised tariffs and established a treasury system that lasted until 1913.

His time as U.S. president is most notable for the largest expansion in total land area of the nation's boundaries exceeding even the Louisiana Purchase, through the negotiated establishment of the Oregon Territory and the purchase of 1.2 million square miles (3.1 million square kilometers) through the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the Mexican-American War. The expansionism, however, opened a furious debate over slavery in the new territories and was in part resolved by the Compromise of 1850. He signed the Walker Tariff that brought an era of near free trade to the country until 1861. He oversaw the opening of the United States Naval Academy and the Washington Monument, and the issuance of the first postage stamp in the United States. James Polk came into the presidency amid great turmoil with in his party. He wanted only to be nominated as vice president, but he won his party's nomination on the ninth ballot. As an offering to preserve the stability of the democratic party, Polk vowed to serve only one term. In his view, the presidency of the United States was not an office to be sought, but by the same token, not one to decline.

Early life

James Polk was born Pineville, North Carolina in 1795. He was the oldest of ten children and suffered from poor health. His father, Samuel Polk, was a slaveholder farmer and surveyor. His mother, Jane Knox, was a descendant of the Scottish religious reformer John Knox. In 1806, the Polk family moved to Tennessee, settling near Duck River in what is now Maury County. The family grew prosperous, with Samuel Polk becoming one of the leading planters of the area.

At age 17, Polk underwent what was then considered experimental surgery to remove gallstones. This was a medically risky procedure in the early nineteenth century. Without the benefit of modern sterilization, or anesthesia, Polk remarkably survived the surgery. Because of his ill health, his education was informal until 1813, when he enrolled in a Presbyterian school in Columbia, Tennessee. Polk soon transferred to a more challenging school and, in 1816, returned to North Carolina to attend the University at Chapel Hill. The future president excelled, graduating with honors in 1818. He returned to Tennessee in 1819, where he studied law under Felix Grundy, the leading lawyer in Nashville. There, in 1820, Polk began his own law practice.

Political career

Polk was brought up as a Jeffersonian Democrat, as his father and grandfather were strong supporters of Thomas Jefferson. The first public office Polk held was that of chief clerk of the Senate of Tennessee (1821–1823); he resigned the position in order to run his successful campaign for the state legislature. During his first term in the state legislature, he courted Sarah Childress. They married on January 1, 1824.

Polk became a supporter and close friend of Andrew Jackson, then the leading politician of Tennessee. In 1824, Jackson ran for President, and Polk campaigned for a seat in the House of Representatives. Polk succeeded, but Jackson was defeated. Though Jackson had won the popular vote, neither he nor any of the other candidates John Quincy Adams, Henry Clay, or William H. Crawford had obtained a majority of the electoral vote, allowing the House of Representatives to select the victor. In his first speech, Polk expressed his belief that the House's decision to choose Adams was a violation of the will of the people; he even proposed that the Electoral College be abolished.

As a Congressman, Polk was a firm supporter of Jacksonian democracy. He opposed the Second Bank of the United States, favored gold and silver over paper money; expressly distrusted banks; and preferred agricultural interests over industry. This behavior earned him the nickname "Young Hickory," an allusion to Andrew Jackson's sobriquet, "Old Hickory." After Jackson defeated John Quincy Adams in the presidential election of 1828, Polk rose in prominence, becoming the leader of the pro-Administration faction in Congress. As chairman of the powerful U.S. House Committee on Ways and Means, he lent his support to the President in the conflict over the National Bank.

Soon after Polk became speaker in 1835, Jackson left office, to be succeeded by fellow Democrat Martin Van Buren. Van Buren's term was a period of heated political rivalry between the Democrats and the Whigs, with the latter often subjecting Polk to insults, invectives, and challenges to duels.

In 1838, the political situation in Tennessee had changed. The Democratic Party lost the governorship three years earlier for the first time in the state's history. The Democrats were able to convince Polk to return to Tennessee. Leaving Congress in 1839, Polk became a candidate in the Tennessee gubernatorial election, narrowly defeating fellow Democrat Newton Cannon by 2,500 votes. Though he revitalized the party's standing in Tennessee, his victory could not put a stop to the decline of the Democratic Party elsewhere in the nation. In the presidential election of 1840, Martin Van Buren was overwhelmingly defeated by a popular Whig, William Henry Harrison. Polk lost his re-election bid to a Whig, James C. Jones. He challenged Jones in 1843, but was defeated once again.

Election of 1844

Polk modestly had pinned his hopes on being nominated for vice-president at the Democratic National Convention, which began on May 27, 1844. The leading contender for the presidential nomination was former President Martin Van Buren; other candidates included Lewis Cass and James Buchanan. The primary point of political contention involved the Republic of Texas, which, after declaring independence from Mexico in 1836, had asked to join the United States. Van Buren opposed the annexation but in doing so lost the support of many Democrats, including former President Andrew Jackson, who was still wielding great influence. On the convention's first ballot, Van Buren won a simple majority, but did not attain the two-thirds superiority required for nomination. After six more ballots were cast, it became clear that Van Buren would not win the required majority. Polk was put forth as a "dark horse" candidate. The eighth ballot was also indecisive, but on the ninth, the convention unanimously nominated Polk, who had by then garnered Jackson's support. Despite having served as speaker of the House of Representatives, he was largely unknown.

When advised of his nomination, Polk replied: "It has been well observed that the office of President of the United States should neither be sought nor declined. I have never sought it, nor should I feel at liberty to decline it, if conferred upon me by the voluntary suffrages of my fellow citizens." Because the Democratic Party was splintered into bitter factions, Polk promised to serve only one term if elected, hoping that his disappointed rival Democrats would unite behind him with the knowledge that another candidate would be chosen in four years.

Polk's Whig opponent in the U.S. presidential election, 1844 was Henry Clay of Kentucky. Incumbent Whig President John Tyler; a former Democrat; had become estranged from the Whigs and was not nominated for a second term. The question of the Texas Annexation, which was at the forefront during the Democratic Convention, once again dominated the campaign. Polk was a strong proponent of immediate annexation, while Clay presented a more equivocal and vacillating position.

Another campaign issue, also relating to westward expansion, involved the Oregon Country, then under the joint occupation of the United States and Great Britain. The Democrats had championed the cause of expansion, informally linking the controversial Texas annexation issue with a claim to the entire Oregon Country, thus appealing to both Northern and Southern expansionists. Polk's support for westward expansion was consistent, what Democrat advocate John L. O'Sullivan would call "Manifest Destiny"; and likely played an important role in his victory, as opponent Henry Clay hedged his position on this as well.

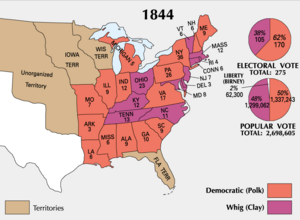

In the election, Polk won in the South and West, while Clay drew support in the Northeast. Polk lost both his home state of Tennessee and his birth state of North Carolina. Polk won the crucial state of New York, where Clay lost supporters to the third-party candidate James G. Birney. Polk won the popular vote by a margin of about 38,000 out of 2.6 million, and took the Electoral College with 170 votes to Clay's 105. Polk was the first, and as yet the only, former Speaker of the House of Representatives to be elected President.

Presidency 1845-1849

When he took office on March 4, 1845 as the eleventh president, Polk, at 49, became the youngest man to assume the presidency up to that time. According to a story told decades later by George Bancroft, Polk set four clearly defined goals for his administration: The re-establishment of the Independent Treasury System, the reduction of tariffs, acquisition of some or all land involved in the Oregon boundary dispute, and the purchase of California from Mexico. Resolved to serve only one term, he accomplished all these objectives in just four years. By linking new lands in the Oregon territories with no slavery and Texas with slavery he hoped to satisfy both North and South.

In 1846, Congress approved the Walker tariff, named after Robert J. Walker, the United States Secretary of the Treasury. The tariff represented a substantial reduction of the Whig-backed Tariff of 1842. The new law abandoned ad valorem tariffs; instead, rates were made independent of the monetary value of the product. Polk's actions were popular in the South and West; however, they earned him the contempt of many protectionists in Pennsylvania.

In 1846, Polk approved a law restoring the Independent Treasury System, under which government funds were held in the Treasury, rather than in banks or other financial institutions.

Slavery

Polk's views on slavery made his presidency bitterly controversial among the proponents of slavery, its opponents, and the advocates of compromise. The effect of his own career as a plantation slaveholder on his policymaking has been argued. During his presidency many abolitionists harshly criticized him as an instrument of the "Slave Power," and claimed that the expansion of slavery lay behind his support for the annexation of Texas and subsequent Mexican-American War. Polk's diary reveals that he believed slavery could not exist in the territories won from Mexico, but refused to endorse the Wilmot Proviso. Polk argued instead for extending the Missouri Compromise line all the way to the Pacific Ocean. This would have prohibited the expansion of slavery north of 36° 30' and west of Missouri, but allow it below that latitude if approved by eligible voters in the territory.

Foreign policy

Polk was committed to expansion; Democrats believed that opening up more farms for yeoman farmers was critical for the success of republican virtue. To avoid the sort of sectional battles that had prevented annexation of the Republic of Texas, he sought new territory in the north. That meant a strong demand for all or part of the disputed Oregon territory, as well as Texas. Polk then sought to purchase California, which Mexico had neglected.

Texas

President Tyler had interpreted Polk's victory as a mandate for the annexation of Republic of Texas. Acting quickly because he feared British designs on Texas, Tyler urged Congress to pass a joint resolution admitting Texas to the Union; Congress complied on February 28, 1845. Texas promptly accepted the offer and officially became a state on December 29, 1845. The annexation angered Mexico, however, which had succumbed to heavy British pressure and had offered Texas its semi-independence on the condition that it should not attach itself to any other nation. Mexican politicians had repeatedly warned that annexation meant war.

Oregon territory

Polk also sought to address the Oregon boundary dispute. Since 1818, the territory had been under the joint occupation and control of Great Britain and the United States. Previous U.S. administrations had offered to divide the region along the 49th parallel, which was not acceptable to the British, who had commercial interests along the Columbia River. Although the Democratic platform had asserted a claim to the entire region, Polk was prepared to quietly compromise. When the British again refused to accept the 49th parallel boundary proposal, Polk broke off negotiations and returned to the "All Oregon" position of the Democratic platform, which escalated tensions along the border.

Polk was not prepared to wage war with the British, however, and agreed to compromise with the British Foreign Secretary, George Hamilton-Gordon, 4th Earl of Aberdeen. The Oregon Treaty of 1846 divided the Oregon Country along the 49th parallel, the original American proposal. Although there were many who still clamored for the whole of the territory, the treaty was approved by the Senate. The portion of Oregon territory acquired by the United States would later form the states of Washington, Oregon, and Idaho, and parts of the states of Montana and Wyoming.

War with Mexico

After the Texas annexation, Polk turned his attention to California, hoping to acquire the territory from Mexico before any European nation did so. The main interest was San Francisco Bay as an access point for trade with Asia. In 1845, he sent diplomat John Slidell to Mexico to purchase California and New Mexico for $30 million. Slidell's arrival caused political turmoil in Mexico after word leaked out that he was there to purchase additional territory and not to offer compensation for the loss of Texas. The Mexicans refused to receive Slidell, citing a technical problem with his credentials. Meanwhile, to increase pressure on Mexico to negotiate, in January 1846, Polk sent troops under General Zachary Taylor into the area between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande River; territory that was claimed by both Texas and Mexico.

Days after Slidell's return, Polk received word that Mexican forces had crossed the Rio Grande area and killed eleven American soldiers. Polk now made this the casus belli, and in a message to Congress on May 11, 1846, he stated that Mexico had "invaded our territory and shed American blood upon the American soil." He did not point out that the territory in question was disputed and did not unequivocally belong to the United States. Several congressmen expressed doubts about Polk's version of events, but Congress overwhelmingly approved the declaration of war, with many Whigs fearing that opposition would cost them politically. In the House, anti-slavery Whigs led by John Quincy Adams voted against the war. Among Democrats, Senator John C. Calhoun was the most notable opponent of the declaration.

By the summer of 1846, New Mexico had been conquered by American forces under General Stephen W. Kearny. Meanwhile, Army captain John C. Frémont led settlers in northern California to overthrow the small Mexican garrison in Sonoma. General Zachary Taylor, at the same time, was having success on the Rio Grande River. The United States also negotiated a secret arrangement with Antonio López de Santa Anna, the Mexican general and dictator who had been overthrown in 1844. Santa Anna agreed that, if given safe passage into Mexico, he would attempt to persuade those in power to sell California and New Mexico to the United States. Once he reached Mexico, however, he reneged on his agreement, declared himself President, and tried to drive the American invaders back. Santa Anna's efforts, however, were in vain, as generals Zachary Taylor and Winfield Scott destroyed all resistance.

Polk sent diplomat Nicholas Trist to negotiate with Mexico. Trist successfully negotiated the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, which Polk agreed to ratify, ignoring calls from Democrats who demanded the annexation of the whole of Mexico. The treaty added 1.2 million square miles (3.1 million square kilometers) of territory to the United States; Mexico's size was halved, the United States increased by a third. California, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, Utah, and parts of Colorado and Wyoming were all carved from the Mexican Cession. The treaty also recognized the annexation of Texas and acknowledged American control over the disputed territory between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande. Mexico, in turn, received the sum of $15 million ($297 million in 2005) for the land, which was half the same offer made by the United States for the land prior to the war. Under great duress, Mexico accepted the offer. The war involved less than 20,000 American casualties but more than 50,000 Mexican casualties. It cost the United States nearly $100 million including the money given Mexico.

Administration and Cabinet

| OFFICE | NAME | TERM |

| President of the United States | James K. Polk | 1845–1849 |

| Vice President of the United States | George M. Dallas | 1845–1849 |

| United States Secretary of State | James Buchanan | 1845–1849 |

| United States Secretary of the Treasury | Robert J. Walker | 1845–1849 |

| United States Secretary of War | William L. Marcy | 1845–1849 |

| Attorney General of the United States | John Y. Mason | 1845–1846 |

| Nathan Clifford | 1846–1848 | |

| Isaac Toucey | 1848–1849 | |

| Postmaster General of the United States | Cave Johnson | 1845–1849 |

| United States Secretary of the Navy | George Bancroft | 1845–1846 |

| John Y. Mason | 1846–1849 | |

Supreme Court appointments

Polk appointed the following Justices to the Supreme Court of the United States:

- Levi Woodbury–1845

- Robert Cooper Grier–1846

Congress

29th Congress (March 4, 1845–March 3, 1847) U.S. Senate: 31 Democrats, 31 Whigs, 1 Other U.S. House of Representatives: 143 Democrats, 77 Whigs, 6 Others

30th Congress (March 4, 1847–March 3, 1849) U.S. Senate: 36 Democrats, 21 Whigs, 1 Other U.S. House of Representatives: 115 Whigs, 108 Democrats, 4 Others

States admitted to the Union

- Texas–1845

- Iowa–1846

- Wisconsin–1848

Post-presidency

Polk's considerable political accomplishments took their toll on his health. Full of enthusiasm and vigor when he entered office, Polk left the White House on March 4, 1849, exhausted by his years of public service. He lost weight and had deep lines and dark circles on his face. He is believed to have contracted cholera in New Orleans, Louisiana on a good will tour of the South. He died at his new home, Polk Place, in Nashville, Tennessee, at 3:15 p.m. on June 15, 1849, with his wife Sarah at his side. She lived at Polk Place for over forty years after his passing, a retirement longer than that of any other First Lady of the United States. She died on August 14, 1891. President and Mrs. Polk are buried in a tomb on the grounds of the Tennessee State Capitol Building.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bergeron, Paul H. The Presidency of James K. Polk. Lawrence, Kan.: University Press of Kansas, 1987. ISBN 0700603190

- Dusinberre, William. Slavemaster President: The Double Career of James Polk. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 0195157354

- Dusinberre, William. "President Polk and the Politics of Slavery," American Nineteenth Century History 2002 3(1): pp.1-16.

- Eisenhower, John S. D. "The Election of James K. Polk, 1844," Tennessee Historical Quarterly 1994 53(2): pp.74-87.

- Haynes, Sam W. James K. Polk and the Expansionist Impulse. New York: Pearson Longman, 2006. ISBN 0321370740

- Kornblith, Gary J. "Rethinking the Coming of the Civil War: a Counterfactual Exercise," Journal of American History 2003 90(1): pp.76-105. ISSN 0021-8723

- Leonard, Thomas M. James K. Polk: A Clear and Unquestionable Destiny. Wilmington, Del.: S.R. Books, 2001. ISBN 0842026479

- McCormac, Eugene Irving. James K. Polk: A Political Biography. 2 v., Newton, CT: American Political Biography Press, 1995.

- McCoy, Charles A. Polk and the Presidency. New York: Haskell House Publishers, 1973. ISBN 0838316867

- Seigenthaler, John. James K. Polk. New York: Times Books, 2004. ISBN 0805069429

- Morrison, Michael A. "Martin Van Buren, the Democracy, and the Partisan Politics of Texas Annexation," Journal of Southern History 1995 61(4): pp.695-724.

- Sellers, Charles. James K. Polk, Jacksonian, 1795-1843. (v.1) and James K. Polk, Continentalist, 1843-1846. (v.2) Norwalk, Conn.: Easton Press, 1987.

Primary sources

- Polk, James K. The Diary of James K. Polk During His Presidency, 1845-1849 edited by Milo Milton Quaife, 4 vols. Chicago: A. C. McClurg, 1910.

- Polk; the diary of a president, 1845-1849, covering the Mexican War, the acquisition of Oregon, and the conquest of California and the Southwest London, New York: Longmans, Green and Co., 1929 abridged edition by Allan Nevins.

- Cutler, Wayne, et. al. Correspondence of James K. Polk 10 vol., Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 1969, 2004; University of Tennessee Press, 2004. ISBN 1572333049

External links

All links retrieved March 18, 2018.

- Inaugural Address of James K. Polk.

- First State of the Union Address (1845).

- Second State of the Union Address (1846).

- Third State of the Union Address (1847).

- Fourth State of the Union Address (1848).

- Obituary of President Polk in The Liberator (June 22, 1849).

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.