Hugh Despenser the younger

Hugh Despenser, 1st Lord Despenser (1286 – November 24, 1326), sometimes referred to as "the younger Despenser," was keeper of a number of castles and towns in England and Wales, some of which he possessed legally, some he obtained illegally. From 1314, he adopted the title Lord of Glamorgan. In 1318, he became Chamberlain to Edward II of England. By 1321, he and his father had offended to many members of the nobility that they were forced to flee to. Hugh spent the next year as a pirate in the English Channel. He was re-instated at court a year later. Hugh and his father were so powerful that they more or less ran the country, manipulating Edward, with whom Hugh may have had a homosexual relationship.

In 1326, Edward's wife, Isabella, and Roger Mortimer invaded England to end the power of the Dispensers and Edward's ineffectual rule. Most of the country rallied to the Queen's side. Mortimer became de facto ruler for the next three years. Both Dispensers were executed for treason. Hugh Despenser the Younger was a selfish man who manipulated others to accumulate wealth for himself, to gain power and influence. King Edward's weakness presented him with an ideal opportunity to act as the power behind the throne. He had no regard for justice and had no scruples in taking advantage of widowed women who had little change of protecting their property. Hugh's legacy is a reminder that power corrupts. Yet, although he ignored Parliament, by the end of his life, Parliament was beginning to assert the right to share in power. It appropriated to itself the task of curbing excesses and of minimizing the possibility of one person, king or a manipulator of kings, ignoring on people's rights, confiscating their property and governing with no concern for the common good.

Life

Hugh Despenser the younger was the son and heir of Hugh le Despenser, later Earl of Winchester, by Isabel Beauchamp, daughter of William de Beauchamp, 9th Earl of Warwick. Hugh's father was created 1st Baron le Despencer in 1295. In 1322, he was elevated as Earl of Winchester.

In May 1306, Hugh was knighted, and that summer he married Eleanor de Clare, daughter of Gilbert de Clare, 9th Lord of Clare and 7th Earl of Hertford and Joan of Acre. Her grandfather, Edward I, owed Hugh's father vast sums of money, and the marriage was intended as a payment of these debts. When Eleanor's brother was killed at the Battle of Bannockburn, she unexpectedly became one of the three co-heiresses to the rich Gloucester earldom, and in her right Hugh inherited Glamorgan and other properties. In just a few short years Hugh went from a landless knight to one of the wealthiest magnates in the kingdom. Hugh and his wife had "nine or ten children over a period of about sixteen or seventeen years" and an apparently happy relationship.[1]

Eleanor was also the niece of the new king, Edward II of England, and this connection brought Hugh closer to the English royal court. He joined the baronial opposition to Piers Gaveston, the king's favorite, and Hugh's brother-in-law, as Gaveston was married to Eleanor's sister. Eager for power and wealth, Hugh seized Tonbridge Castle in 1315. The next year he murdered Llywelyn Bren, a Welsh hostage in his custody. Hugh's father became Edward's chief adviser following Galveston's execution in 1312. He was often sent to represent the king in negotiations in Europe.

Royal Chamberlain

Hugh became royal chamberlain in 1318. Parliament had been eager to stop Edward's spending on lavish entertainment while the economy languished and in 1311, it established a council of 21 leading barons to supervise Edward under a set of Ordinances. From 1314 to 1318, Thomas Plantagenet, 2nd Earl of Lancaster was Chief Councillor, appointed by Parliament, and effectively governed England. However, by 1318, Thomas Lancaster had lost support and was forced out of office, accepting a lesser role. His removal made Hugh's appointment possible. As a royal courtier, Hugh maneuvered into the affections of King Edward, displacing the previous favorite, Roger d'Amory. Barons who had supported his appointment soon saw him as a worse version of Gaveston. By 1320, his greed was running free.

Hugh seized the Welsh lands of his wife's inheritance, ignoring the claims of his two brothers-in-law. He forced Alice de Lacy, Countess of Lincoln, to give up her lands, cheated his sister-in-law Elizabeth de Clare out of Gower and Usk, and allegedly had Lady Baret's arms and legs broken until she went insane. He also supposedly vowed to be revenged on Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March because Mortimer's grandfather had murdered Hugh's grandfather, and once stated (though probably in jest) that he regretted he could not control the wind. By 1321, he had earned many enemies in every stratum of society, from Queen Isabella to the barons to the common people. There was even a bizarre plot to kill Hugh by sticking pins in a wax likeness of him.

Exile

Edward and the Dispenser's were ignoring Parliament and ruling without consulting the barons, even though Parliament had passed the Ordinances of 1310-11, limiting his power. In 1321, Edward banned the Barons and other aristocrats from gathering in the House of Lords, fearing that they were plotting against him. When Edward refused to dismiss Hugh or to take any action against him for the illegal seizure of property, the barons gathered "800 men-at-arms and 10,000 footmen" and devastated Glamorgan "from end to end"[2] This is known as the Despenser War. Finally the barons convinced Parliament to banish both Dispensers. Hugh and his father went into exile in August 1321. His father fled to Bordeaux, France and Hugh became a pirate in the English Channel, "a sea monster, lying in wait for merchants as they crossed his path."[3] Edward, however, successfully moved against the rebel Barons at the Battle of Boroughbridge March 16, 1322, and immediately recalled his favorites. The pair returned. Edward reinstated Hugh as his chamberlain, and created High's father Earl of Winchester. Hugh's time in exile had done nothing to quell his greed, his rashness, or his ruthlessness. Thomas Lancaster was found guilty of treason and executed. Fellow rebel, Roger Mortimer was imprisoned but escaped to France.

The tyranny

The time from the Despensers' return from exile until the end of Edward II's reign was a time of uncertainty in England. With the main baronial opposition leaderless and weak, having been defeated at the Battle of Boroughbridge, and Edward willing to let them do as they pleased, the Despensers were left unchecked. At York in 1322, Edward convened Parliament and revoked the Ordinances limiting his power. Edward and the Despensers grew rich through corruption and maladministration. "For four years," writes Given-Wilson, "Edward and the Despensers ruled England as they pleased, brooking no opposition, growing fat on the proceeds of confiscated land and disinherited heirs."[4] The dispossessed were often wealthy widows. Hugh has been described as the "real ruler of England" at this point.[1] This period is sometimes referred to as the "Tyranny." This maladministration caused hostile feeling for them and, by proxy, Edward II. Edward and the Despensers simply ignored the law of the land, bending it to suit their interests.

Queen Isabella had a special dislike for the man, who was now one of the richest nobles in England. Various historians have suggested, and it is commonly believed, that he and Edward had an ongoing sexual relationship. Froissart states "he was a sodomite, even it is said, with the King."[5] Some speculate it was this relationship that caused the Queen's dislike of him. Others, noting that her hatred for him was far greater than for any other favorite of her husband, suggest that his behavior towards herself and the nation served to excite her particular disgust. Weir speculates that he had raped Isabella and that was the source of her hatred.[6] While Isabella was in France to negotiate between her husband and the French king over Edward's refusal to pay homage for his French fief, she formed a liaison with Roger Mortimer and began planning an invasion. Hugh supposedly tried to bribe French courtiers to assassinate Isabella, sending barrels of silver as payment. Others suggest that Hugh "used his influence over Edward and as Chamberlain to prevent Isabella from seeing her husband or" form "wielding any political influence.[1]

Edward's deposition and Hugh's execution

Roger Mortimer and the Queen invaded England in October 1326. Their forces only numbered about 1,500 mercenaries to begin with, but the majority of the nobility rallied to them throughout October and November. By contrast, very few people were prepared to fight for Edward II, mainly because of the hatred which the Despensers had aroused. The Despensers fled West with the King, with a sizable sum from the treasury. The escape was unsuccessful. The King and Hugh were deserted by most of their followers, and were captured near Neath, in mid-November. King Edward was placed in captivity and later deposed. At his coronation, he had promised to keep the peace, to maintain justice and to obey the laws of the "community." The last was a new oath and when he failed to keep this promise, the community's representatives in Parliament deposed him.[7] Hugh's father was executed, at Bristol, and Hugh himself was brought to trial.

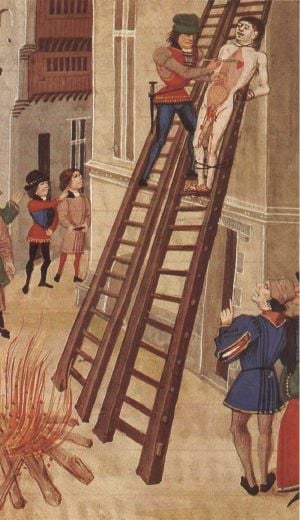

Hugh tried to starve himself before his trial, but face trial he did on November 24, 1326, in Hereford, before Mortimer and the Queen. He was judged a traitor and a thief, and sentenced to public execution by hanging, drawing and quartering. Additionally, he was sentenced to be disemboweled for having procured discord between the King and Queen. Treason had also been the grounds for Gaveston's execution; the belief was that these men had misled the King rather than the King himself being guilty of folly. Immediately after the trial, he was dragged behind four horses to his place of execution, where a great fire was lit. He was stripped naked, and biblical verses denouncing arrogance and evil were written on his skin.[8] He was then hanged from a gallows 50 ft (15 m) high, but cut down before he could choke to death, and tied to a ladder in full view of the crowd. The executioner then climbed up beside him, and sliced off his penis and testicles. These were then burnt in front of him, while he was still alive and conscious. Subsequently, the executioner plunged his knife into his abdomen, and slowly pulled out, and cut out, his entrails and heart, which were likewise burnt before the ecstatic crowd. Finally, his corpse was beheaded, and his body cut into four pieces, and his head was mounted on the gates of London.[9]

Edward was officially deposed by Parliament in January 1327. In deposing Edward, Parliament stated that Edward

was incompetent to govern, that he had neglected the business of the kingdom for unbecoming occupations … that he had broken his coronation oath, especially in the matter of doing justice to all, and that he had ruined the realm.[10]

Parliament then confirmed his son, Edward III as king, with Mortimer as regent until Edward assumed power for himself in 1330. It was Parliament that then found Mortimer found guilty of "usurping royal power" and of "causing dissension between Edward II and his Queen" and ordered his execution. Like Hugh, he was hung, drawn and quartered. [11]

Heirs

His eldest son, Hugh, died in 1349 without any heirs. His son, Edward Despenser married Elizabeth, daughter of Bartholomew, lord Burghersh, fought at the Battle of Poitiers and in other battles in France. He was made a knight of the Garter, and died in 1375. His son, Thomas le Despenser, became Earl of Gloucester. Edward's daughter, Elizabeth married John FitzAlan, 2nd Baron Arundel, ancestor of the poet, Shelley, Percy Bysshe.

Legacy

After his death, his widow asked to be given the body so she could bury it at the family's Gloucestershire estate, but only the head, a thigh bone and a few vertebrae were returned to her.[12]

What may be the body of Despenser was identified in February 2008, at Hulton Abbey in Staffordshire. The skeleton, which was first uncovered during archaeological work in the 1970s, appeared to be the victim of a drawing and quartering as it had been beheaded and chopped into several pieces with a sharp blade, suggesting a ritual killing. Furthermore, it lacked several body parts, including the ones given to Despenser's wife. Radiocarbon analysis dated the body to between 1050 and 1385, and later tests suggested it to be that of a man over 34 years old. Despenser was 40 at the time of his death. In addition, the Abbey is located on lands that belonged to Hugh Audley, Despenser's brother-in-law, at the time.[12]

No book-length biographical study of Hugh Despenser exists, although The Tyranny and Fall of Edward II: 1321–1326 by historian Natalie Fryde is a study of Edward's reign during the years that the Despensers' power was at its peak. Fryde pays particular attention to the subject of the Despensers' ill-gotten landholdings. The numerous accusations against the younger Despenser at the time of his execution have never been the subject of close critical scrutiny, although Roy Martin Haines called them "ingenuous"—"another piece of propaganda that puts all blame for the ills of the reign on one man and his father."[13]

Despite the crucial and disastrous role he played in the reign of Edward II, Despenser is almost a minor character in Christopher Marlowe's play Edward II (1592), where as "Spencer" he is little more than a substitute for the dead Gaveston. In 2006, he was selected by BBC History Magazine as the fourteenth century's worst Briton.[14]

Hugh Despenser the younger was a selfish man who manipulated others to accumulate wealth for himself. Edward's weakness presented him with an ideal opportunity to act as the power behind the throne. He had no regard for justice. Edward was king, and Hugh his senior adviser at a time when the relationship between king and people was changing. In place of the nation as more or less the personal possession of the monarch, the view of the nation as a community or commonwealth was emerging, in which all freemen (but not yet women) had rights and responsibilities. The kingly power, it was still believed, was part of the natural order but even the king had to govern justly, and consult his barons and the representatives of the Commons to raise and spend money, as well as to wage war. On the one hand, Edward and his Chamberlain tried to disregard Parliament and to rule without consulting either the House of Commons or the House of Lords. At this point in English history, Parliamentary government was still a long way off, yet increasingly kings could not rule without Parliament. Despite being marginalized, it was Parliament that sent Hugh into exile in 1322. Since it was Parliament that officially deposed Edward, it was also Parliament that legitimized Edward III's succession. It was Parliament that found Mortimer guilty of usurping royal power, and ordered his execution. Arguably, one positive result of Hugh's attempts to appropriate power was a strengthening of Parliament's supervisory role. It became more and more difficult for any individual, even for the King, to exercise power alone.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Alianore, Hugh le Despenser the Younger, Medieval Miniatures. Retrieved October 19, 2008.

- ↑ Chronicle, Hugh Le Despenser the Younger. Retrieved October 19, 2008.

- ↑ Mortimer (2006), 111.

- ↑ Given-Wilson (1987), 32.

- ↑ Froissart and Brereton (1978), 44.

- ↑ Weir (2005).

- ↑ Prestwich, 25.

- ↑ Mortimer (2006), 160.

- ↑ Kastenbaum (2004), 193-4.

- ↑ Cross, 123.

- ↑ Sidney Lee and Leslie Stephen, Dictionary of National Biography: Index and Epitome (London: Oxford University Press), 909.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Laura Clout, Abbey body identified as gay lover of Edward II, The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved October 19, 2008.

- ↑ Haines (2003), 185.

- ↑ BBC, 'Worst' historical Britons list. Retrieved October 19, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cross, Arthur Lyon. 1920. A Shorter History of England and Greater Britain. London: Macmillan

- Froissart, Jean, and Geoffrey Brereton. 1978. Chronicles. The Penguin classics. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin Books. ISBN 9780140442007.

- Fryde, Natalie. 1979. The Tyranny and Fall of Edward II, 1321-1326. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521222013.

- Given-Wilson, Chris. 1987. The English Nobility in the Late Middle Ages: The Fourteenth Century Political Community. London, UK: Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 9780710204912.

- Haines, Roy Martin. 2003. King Edward II: Edward of Caernarfon, his Life, his Reign, and its Aftermath, 1284-1330. Montreal, CA: McGill-Queen's Univ. Press. ISBN 9780773524323.

- Kastenbaum, Robert. 2004. On our Way: The Final Passage Through Life and Death. Life passages. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520218802.

- Marlowe, Christopher. 1990s. Edward the Second. Champaign, IL: Project Gutenberg. ISBN 9780585049526.

- Mortimer, Ian. 2006. The Greatest Traitor: The Life of Sir Roger Mortimer, Ruler of England, 1327-1330. New York, NY: Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 9780312349417.

- Prestwich, Michael. 2005. Plantagenet England, 1225-1360. The new Oxford History of England. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198228448.

- Weir, Alison. 2005. Queen Isabella: Treachery, Adultery, and Murder in Medieval England. New York, NY: Ballantine Books. ISBN 9780345453198.

External links

All links retrieved July 19, 2024.

- Edward's other great favorite - Hugh Despenser the Younger

- Hugh Le Despenser the Younger Chronicle - Your Place in History.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.