Isabella of France

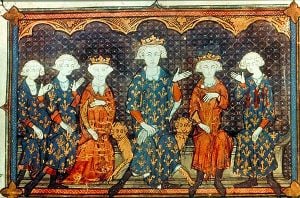

Isabella of France (c. 1295 – August 22, 1358), later referred to as the She-Wolf of France, was the Queen consort of Edward II of England, mother of Edward III and Queen Regent 1327 to 1330. She was the youngest surviving child and only surviving daughter of Philip IV of France and Joan I of Navarre. She married Edward on 25 January 1308 and was crowned Queen consort on February 25, 1308. Although she bore Edward four children, including his heir, the bi-sexual king spent more time with his male favorites, reaping gifts and honors on them and neglecting governance. Edward faced constant baronial revolt and from 1311 until 1318 Parliament succeeded in curbing his power. In 1325, Isabella went to France to negotiate terms with her brother, who had seized Edward's French possessions. There, she entered an adulterous affair with Roger Mortimer, who had escaped from the Tower of London in 1823 where he had been imprisoned for his role in the revolt of 1321-1322.

With Mortimer, Isabella plotted an invasion of England to depose Edward. In 1326, they successfully invaded. Edward was deposed and later murdered. From 1327 until 1330, Isabella and Mortimer ruler as co-regents on behalf of the future Edward III of England. Roger's rule, however, was despotic and self-serving. The young prince was provoked to assume power for himself, which he did in 1330. Mortimer was executed; Isabella entered retirement, taking orders as a nun. Isabella has attracted the attention of numerous novelists, historians and playwrights. Her legacy is inevitably colored by her adultery and alleged role in Edward's murder. She may have opposed her husband out of a concern to improve governance; it was unfortunate that her partner was almost as corrupt as Edward. Her son, however, would do much to strengthen the authority of parliament, which made it much more difficult for future kings to ignore the public good. It was through Isabella that Edward would claim the French throne, launching the Hundred Years' War to prosecute this. On the one hand, many lives were lost during this war. On the other, parliament was further strengthened as it became more and more reluctant to approve money for wars in which the majority of the population had little interest.

Biography

Early life

Isabella was born in Paris on an uncertain date, probably between May and November 1295, several years younger than her young husband born April of 1284.[1], to King Philip IV of France and Queen Jeanne of Navarre, and the sister of three French kings. Isabella was not titled a 'princess', as daughters of European monarchs were not given that style until later in history. Royal women were usually titled 'Lady' or an equivalent in other languages.

Marriage

While still an infant, Isabella was promised in marriage by her father to Edward II; the intention was to resolve the conflicts between France and England over the latter's continental possession of Gascony and claims to Anjou, Normandy and Aquitaine. Pope Boniface VIII had urged the marriage as early as 1298 but was delayed by wrangling over the terms of the marriage contract. The English king, Edward I had also attempted to break the engagement several times. Only after he died, in 1307, did the wedding proceed.

Isabella's groom, the new King Edward II, looked the part of a Plantagenet king to perfection. He was tall, athletic, and wildly popular at the beginning of his reign. Isabella and Edward were married at Boulogne-sur-Mer on January 25, 1308. Since he had ascended the throne the previous year, Isabella never was titled Princess of Wales.

At the time of her marriage, Isabella was probably about 12 and was described by Geoffrey of Paris as "the beauty of beauties…in the kingdom if not in all Europe."[2]These words may not merely have represented the standard politeness and flattery of a royal by a chronicler, since Isabella's father and brother are described as very handsome men in the historical literature. Isabella was said to resemble her father, and not her mother Jeanne of Navarre, a plump woman of high complexion.[3]This would indicate that Isabella was slender and pale-skinned.

Edward and Isabella did manage to produce four children, and she suffered at least one miscarriage. Their itineraries demonstrate that they were together nine months prior to the births of all four surviving offspring. Their children were:

- Edward of Windsor the future Edward III, born 1312

- John of Eltham, born 1316

- Eleanor of Woodstock, born 1318, married Reinoud II of Guelders

- Joan of the Tower, born 1321, married David II of Scotland

Isabella and the King's favorites

Although Isabella produced four children, the apparently bisexual king was notorious for lavishing sexual attention on a succession of male favorites, including Piers Gaveston and Hugh le Despenser the younger. The barons, jealous of Gaveston's influence (he was a commoner ennobled by Edward) contrived several times to have him banished before actually murdering him in 1312. His behavior at Edward's and Isabella's coronation had been especially shocking; he wore royal purple instead of an earl's cloth of gold, which caused French guests to walk out.[4] He was soon replaced by Despenser, whom Isabella despised, and in 1321, while pregnant with her youngest child, she dramatically begged Edward to banish him from the kingdom. Despenser may have deprived her of some income that was rightfully hers.[5] Despenser and his father, also an adviser to the king, were exiled not only at Isabella's request but at the insistence of the barons, too, disgusted with Edward's profligacy and misrule. The barons staged what amounted to a revolt. Edward, however, was able to attract enough support to crush the baronial rebellion, whose leader, Plantagenet, Thomas, 2nd Earl of Lancaster was executed. Before this act, he had recalled the two Despensers who sat on the tribunal that condemned Plantagenet, the king's cousin, for treason. Another leader of the revolt, Roger Mortimer escaped from imprisonment in the Tower of London. Plantagenet had led an earlier baronial revolt in 1311, when Parliament imposed constraints on Edward's power especially on his financial management. From 1314 until 1318 Plantagent had more or less governed England as parliament's Chief Councilor. An admirer of Simon de Montford, Plantagent favored wide participation in governance. However, when Plantagenent lost the city of Berwick to the Scottish, Edward persuaded the barons to demote him and promoted the younger Despenser in his place (as Chamberlain).

The Despensers' recall seems finally to have turned Isabella against her husband altogether. The next four years saw Edward and the Despensers flout the law by seizing widows' properties and placing themselves above the law. While the nature of her relationship with Roger Mortimer is unknown for this time period, she may have helped him escape from the Tower of London in 1323. Later, she openly took Mortimer as her lover. He was married to the wealthy heiress Joan de Geneville, and the father of 12 children.

Isabella and Mortimer plot revolt

When Isabella's brother, King Charles IV of France, seized Edward's French possessions in 1325, she returned to France, initially as a delegate of the King charged with negotiating a peace treaty between the two countries. However, her presence in France became a focal point for the many nobles opposed to Edward's reign. Doherty says Isabella now started to dress as a widow, saying that as someone had come between her husband and herself, the marriage was "null and void".[6] Isabella gathered an army to oppose Edward, in alliance with Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March. Enraged by this treachery, Edward demanded that Isabella return to England. Her brother, King Charles, replied, "The queen has come of her own will and may freely return if she wishes. But if she prefers to remain here, she is my sister and I refuse to expel her."[7] Edward stopped sending Isabella her allowance. He had already confiscated her property and greatly reduced her income in September 1324, when he first suspected an alliance with Mortimer.[8] The Archbishop of Canterbury had advised Edward not to allow Isabella to "leave the kingdom" before her "estates and household were restored," perhaps suspecting that she would not return.[9]

Despite this public show of support by the King of France, Isabella and Mortimer left the French court in summer 1326 and went to William I, Count of Hainaut in Holland, whose wife was Isabella's cousin. William provided them with eight men of war ships in return for a marriage contract between his daughter Philippa and Isabella's son, Edward. On September 21, 1326, Isabella and Mortimer landed in Suffolk with a small army, most of whom were mercenaries. King Edward II offered a reward for their deaths and is rumored to have carried a knife in his hose with which to kill his wife. Isabella responded by offering twice as much money for the head of Hugh le younger Despenser, who was hanged, drawn and quartered November 24, 1326. This reward was issued from Wallingford Castle.

Isabella and Mortimer Co-Regents (1327-1330)

The invasion by Isabella and Mortimer was successful: King Edward's few allies deserted him without a battle; the Despensers were executed for treason. Edward II himself was captured then deposed by Parliament, who appointed his eldest son as Edward III of England. Since the young king was only 14-years-old when he was crowned on February 1, 1327, Isabella and Mortimer ruled as regents in his place. Edward was deposed for misrule and for failing to keep his coronation oath to obey the laws of the "community"; this was a new oath which arguably subjected the king to the authority of Parliament, since no law could now be passed without the consent of both Parliament and king.[10] In deposing Edward, Parliament stated that he:

was incompetent to govern, that he had neglected the business of the kingdom for unbecoming occupations … that he had broken his coronation oath, especially in the matter of doing justice to all, and that he had ruined the realm.[11]

Edward II's death

According to legend, Isabella and Mortimer famously plotted to murder the deposed king in such a way as not to draw blame on themselves, sending the famous order "Edwardum occidere nolite timere bonum est" which depending on where the comma was inserted could mean either "Do not be afraid to kill Edward; it is good" or "Do not kill Edward; it is good to fear."[12] In actuality, there is little evidence of just who decided to have Edward assassinated, and none whatsoever of the note ever having been written. One story has Edward II escaping death and fleeing to Europe, where he lived as a hermit for 20 years.[13]

Mortimer was created Earl of March in 1328. Wealth and honors were heaped on him. He was made constable of Wallingford Castle, and in September 1328 he was created Earl of March. His own son, Geoffrey, mocked him as "the king of folly." He lived like a king although he "did not enjoy power by right but by duplicity and force."[14] During his short time as ruler of England he took over the lordships of Denbigh, Oswestry, and Clun (all of which previously belonged to the Earl of Arundel).

When Edward III turned 18, he and a few trusted companions staged a coup on October 19, 1330 and had both Isabella and Mortimer taken prisoner. The final act that provoked Edward III was the execution of his uncle, Edmund, Earl of Kent who was accused of having helped Edward II. Despite Isabella's cries of "Fair son, have pity on gentle Mortimer," Mortimer was executed for treason one month later in November of 1330.[15]

Her son spared Isabella's life and she was allowed to retire to Castle Rising in Norfolk. She did not, as legend would have it, go insane; she enjoyed a comfortable retirement for eight years and made many visits to her son's court, doting on her grandchildren. Isabella took the habit of the Poor Clares before she died on August 22, 1358, and her body was returned to London for burial at the Franciscan church at Newgate. She was buried in her wedding dress. Edward's heart was interred with her.

Titles and styles

- Lady Isabella of France

- Isabella, by the grace of God, Queen of England, Lady of Ireland and Duchess of Aquitaine

Ancestors

| Isabella of France | Father: Philip IV of France |

Paternal Grandfather: Philip III of France |

Paternal Great-grandfather: Louis IX of France |

| Paternal Great-grandmother: Marguerite of Provence | |||

| Paternal Grandmother: Isabella of Aragon |

Paternal Great-grandfather: James I of Aragon | ||

| Paternal Great-grandmother: Violant of Hungary | |||

| Mother: Joan I of Navarre |

Maternal Grandfather: Henry I of Navarre |

Maternal Great-grandfather: Theobald I of Navarre | |

| Maternal Great-grandmother: Margaret of Bourbon | |||

| Maternal Grandmother: Blanche of Artois |

Maternal Great-grandfather: Robert I of Artois | ||

| Maternal Great-grandmother: Matilda of Brabant |

Legacy

The sobriquet "she-wolf of France" was appropriated from Shakespeare's Henry VI, Part 3, where it is used to refer to Henry's Queen, Margaret of Anjou with the obvious implication that Isabella was more of a man than Edward II. Her legacy is inextricably linked with those of her husband, Edward and lover, Roger Mortimer. Neither man ruled competently. Edward wasted money, showering gifts on his favorites. Mortimer accumulated wealth for himself. Isabella was a gifted woman who found herself caught up in tumultuous times. Edward was faced by three rebellions, losing his life after the final revolt of which Isabella was herself the co-leader. Then her lover and co-regent, removed from power, was executed for treason. She was both the victim of circumstances, of Edward's debauchery and faithlessness. Committing adultery, which colors any assessment of her legacy, was immoral. Doherty says that until her visit to France, there is no evidence that Isabella had been unfaithful and surmises that her alienation from Edward went deeper than her dislike of his favorite. Doherty speculates that Edward may have proposed a three-part "marriage" involving Isabella, himself and his male-lover.[16] Doherty points out that both the Pope and the English bishops supported Isabella while she was in self-imposed exile. The pope wrote to Edward II, upbraiding him for his treatment of Isabella and "for his lack of good government."[17] Nor can it be ignored that she was allowed to take orders as a nun towards the end of her life.

Did Isabella move against Edward only for personal revenge, or because with the Pope she wanted to see England governed well? The wording of Parliament's statement regarding Edward's removal suggests that she was interested in restoring justice and good governance. Unfortunately, she became as much a tool of Mortimer as Edward had been of his favorites. At least in part, it is a mother of Edward III that Isabella is to be remembered. Edward III's reign is remembered for significant developments in Parliamentary governance. Isabella was also a mother; her firstborn son, Edward III, grew up with unfortunate examples for both parents and rulers; although his rule resulted in the strengthening of British parliamentary power. The House of Commons became a much more significant chamber, consolidating its right to approve new taxes which not only had to be justified but shown to benefit the people. The office of Speaker was also established. Through his mother, Edward III would claim the French throne. This set the Hundred Years' War in motion, which resulted in the loss of many lives. On the other hand, as the landed nobility and aristocracy grew tired on having to pay for and fight in wars that brought them no benefit, they began to assert their right in Parliament to refuse to pay for senseless wars. This led to further strengthening of parliament's power and role in governance of the nation.

Isabella in fiction

Isabella features in a great deal of fictional literature. She appears as a major character in Christopher Marlowe's play Edward II, and in Derek Jarman's 1991 film based on the play and bearing the same name. She is played by actress Tilda Swinton as a 'femme fatale' whose thwarted love for Edward causes her to turn against him and steal his throne.

In the film Braveheart, directed by and starring Mel Gibson, Isabella was played by the French actress Sophie Marceau. In the film, Isabella is depicted as having a romantic affair with the Scottish hero William Wallace, who is portrayed as the real father of her son Edward III. This is entirely fictional, as there is no evidence whatsoever that the two people ever met one another, and even if they did meet at the time the movie was set, Isabella was only three years old. Wallace was executed in 1305, before Isabella was even married to Edward II (their marriage occurred in January 1308). When Wallace died, Isabella was about ten years old. All of Isabella's children were born many years after Wallace's death, thus it is impossible that Wallace was the father of Edward III.

Isabella has also been the subject of a number of historical novels, including Margaret Campbell Barnes' Isabel the Fair, Hilda Lewis' Harlot Queen, Maureen Peters' Isabella, the She-Wolf, Brenda Honeyman's The Queen and Mortimer, Paul Doherty's The Cup of Ghosts, Jean Plaidy's The Follies of the King, and Edith Felber's Queen of Shadows. She is the title character of The She-Wolf of France by the well-known French novelist Maurice Druon. The series of which the book was part, The Accursed Kings, has been adapted for French television in 1972 and 2005.[18] Most recently, Isabella figures prominently in The Traitor's Wife: A Novel of the Reign of Edward II, by Susan Higginbotham. Also, Ken Follett's 2007 novel, World Without End World Without End uses the alleged murder of Edward II (and the infamous letter) as a plot device. Susan Howatch's Cashelmara and The Wheel of Fortune, two Romans a clef based on the lives of the Plantagenet kings, depict her as a young abused wife and an old widow hidden from her grandchildren in a retirement home run by nuns.

| English royalty | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by: Marguerite of France |

Queen Consort of England 25 January, 1308 - 20 January, 1327 |

Succeeded by: Philippa of Hainault |

| Preceded by: Eleanor of Provence |

Queen mother 1327 - 1358 |

Succeeded by: Catherine of Valois |

See also

Notes

- ↑ She is described as born in 1292 in the Annals of Wigmore, and Piers Langtoft agrees, claiming that she was seven years old in 1299. The French chronicler Guillaume de Nangis and Thomas Walsingham describe her as 12 years old at the time of her marriage in January 1308, placing her birth between the January of 1295 and of 1296. A Papal dispensation by Clement V in November 1305 permitted her immediate marriage by proxy, despite the fact that she was probably only ten years old. Since she had to reach the canonical age of seven before her betrothal in May 1303, and that of 12 before her marriage in January 1308, the evidence suggests that she was born between May and November 1295. Alison Weir. Queen Isabella: treachery, adultery, and murder in medieval England. (New York, NY: Ballantine Books, 2005).

- ↑ Weir, 2005, 23.

- ↑ Thomas Bertram Costain. 1958. The Three Edwards. (Garden City, NY: Doubleday), 82.

- ↑ Ian Mortimer. The Greatest Traitor: The Life of Sir Roger Mortimer, Ruler of England, 1327-1330. (New York, NY: Thomas Dunne Books, 2006), 37.

- ↑ Paul C. Doherty. Isabella and the strange death of Edward II. (New York, NY: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2003), 95.

- ↑ Doherty, 2003, 82, 102.

- ↑ Mortimer, 2006, 143.

- ↑ Mortimer, 2006, 133.

- ↑ Doherty, 2003, 103.

- ↑ Michael Prestwich. Plantagenet England, 1225-1360. (Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, 2005), 25.

- ↑ Arthur Lyon Cross. A Shorter History of England and Greater Britain. (London, UK: Macmillan. 1920), 123.

- ↑ Doherty, 2003, 130.

- ↑ Doherty, 2003, 193.

- ↑ Mortimer, 2006, 219.

- ↑ Mortimer, 2006, 238.

- ↑ Doherty, 2003, 101.

- ↑ Doherty, 2003, 81.

- ↑ Les Rois maudits (The Cursed Kings) (1972) television mini-series. and Les Rois maudits (2005). Internet movie Data Base. Retrieved November 22, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Barnes, Margaret Campbell. 1957. Isabel the Fair. Philadelphia, PA: Macrae Smith.

- Costain, Thomas Bertram. 1958. The Three Edwards. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

- Cross, Arthur Lyon. 1920. A Shorter History of England and Greater Britain. London, UK: Macmillan.

- Doherty, P.C. 2003. Isabella and the strange death of Edward II. New York, NY: Carroll & Graf Publishers. ISBN 9780786711932.

- Doherty, Paul. 2006. The cup of ghosts. Leicester, UK: Howes. ISBN 9781845059279.

- Druon, Maurice. 1956. The accursed kings. New York, NY: Scribner.

- Druon, Maurice, and Humphrey Hare. 1960. The She-Wolf of France. New York, NY: Scribner.

- Felber, Edith. 2006. Queen of shadows: a novel of Isabella, wife of King Edward II. New York, NY: New American Library. ISBN 9780451219527.

- Follett, Ken. 2007. World without end. New York, NY: Dutton. ISBN 9780525950073.

- Fryde, Natalie. 1979. The Tyranny and Fall of Edward II: 1321-1326 New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521222013.

- Gibson, Mel (director), and Randall Wallace (scriptwriter). 2000. Braveheart, Hollywood, CA: Paramount. ISBN 9780792164937.

- Higginbotham, Susan. 2005. The traitor's wife: a novel of the reign of Edward II. New York, NY: iUniverse. ISBN 9780595359592.

- Honeyman, Brenda. 1974. The Queen and Mortimer. London, UK: Hale.

- Howatch, Susan. 1974. Cashelmara. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780671217365.

- Howatch, Susan. 1984. The wheel of fortune. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780671499891.

- Jarman, Derek, Stephen McBride, Ken Butler, Steve Clark-Hall, Steven Waddington, Kevin Collins, and Andrew Tiernan. 1992. Edward II. United Kingdom: Sales Co.

- Lewis, Hilda Winifred. 2006. Harlot Queen. Stroud, UK: Tempus. ISBN 9780752439471.

- Marlowe, Christopher, and Charles R. Forker. 1999. Edward the Second. Revels plays. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719030895.

- Mortimer, Ian. 2006. The Greatest Traitor: The Life of Sir Roger Mortimer, Ruler of England, 1327-1330. New York, NY: Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 9780312349417.

- Peters, Maureen. 1985. Isabella, the she-wolf. London, UK: Hale. ISBN 9780709016854.

- Plaidy, Jean. 1982. The follies of the king. New York, NY: Putnam. ISBN 9780399126901.

- Prestwich, Michael. 2005. Plantagenet England, 1225-1360. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198228448.

- Weir, Alison. 2005. Queen Isabella: treachery, adultery, and murder in medieval England. New York, NY: Ballantine Books. ISBN 9780345453198.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.