Roger de Mortimer, 1st Earl of March (April 25, 1287 – November 29, 1330), an English nobleman, was for three years de facto ruler of England, after leading a successful rebellion against Edward II. Roger was knighted in 1306, having succeeded his father as 3rd Baron Mortimer in 1304. As Lord Lieutenant of Ireland in 1315, he led an army against a rebellious baron and his Scottish supporters. He was himself overthrown by Edward's son, Edward III. In 1321, he joined baronial opposition to Edward's profligacy and misrule and to the illegal activities of Edward's despised chamberlain, Hugh Despenser the younger. With Thomas Plantagenet, 2nd Earl of Lancaster, the king's cousin, Mortimer led a rebellion. Edward, however, crushed the revolt; Thomas was executed but Mortimer escaped to France. When Queen Isabella went to Paris a year later allegedly to negotiate between her husband and her brother, she began an affair with Roger. Together, they planned an invasion of England.

When they landed in England in 1826, their small force was soon joined by discontent English barons. Edward was captured and deposed by Parliament, which appointed his young son to succeed with Isabella and Mortimer as regents. Despenser was hung, drawn, and quartered. In 1328, he was created Earl of March. In 1330, Edward III convened a parliament, assumed power and ordered Mortimer's execution by hanging. Mortimer was accused of usurping royal power and of misrule. In power, Mortimer was no better than the people he had deposed. Mortimer used parliament as a tool to depose Edward but unlike Thomas Plantagenet, he did not respect parliament or the principles of participatory, consultative governance. Increasingly, however, largely due to the reign of the King of whose behalf Mortimer had governed for three years, became too strong to be used as anyone's tool. Parliament's interest became the welfare of the whole community. Although this may not have been his intent, Mortimer's manipulation of parliament aided the process by which constraints on kingly power developed, as parliament asserted the right to supervise and to limit royal power. In time, these constraints would result in full-blown democratic government.

Early life and family history

Mortimer, grandson of Roger Mortimer, 1st Baron Mortimer, was born at Wigmore Castle, Herefordshire, England, the firstborn of Edmund Mortimer, 2nd Baron Mortimer and his wife, Margaret de Fiennes. Edmund Mortimer had been a second son, intended for minor orders and a clerical career, but on the sudden death of his elder brother Ralph, Edmund was recalled from Oxford University and installed as heir. As a boy, Roger was probably sent to be fostered in the household of his formidable uncle, Roger Mortimer of Chirk. It was this uncle who had carried the head of Llywelyn the Last to King Edward I in 1282.

Like many noble children of his time, Roger was betrothed young, to Joan de Geneville, the daughter of a neighboring lord. They were married in 1301, and immediately began a family. Through his marriage with Joan de Geneville, Roger not only acquired increased possessions in the Welsh Marches, including the important Ludlow Castle, which became the chief stronghold of the Mortimers, but also extensive estates and influence in Ireland. However, Joan de Geneville was not an "heiress" at marriage. Her grandfather, Geoffrey de Geneville, at the age of eighty in 1308, conveyed most, but not all, of his Irish lordships to Roger Mortimer, and then retired, notably alive: He finally died in 1314. During his lifetime Geoffrey also conveyed much of the remainder of his legacy, such as Kenlys, to his younger son (the older son Piers having died in 1292), Simon de Geneville, who had meanwhile become Baron of Culmullin through marriage to Joanna FitzLeon. Roger Mortimer therefore succeeded to the lordship of Trim, County Meath (which later reverted to the Crown). He did not succeed however to the Lordship of Fingal.

Fingal descended firstly to Simon de Geneville (whose son Laurence predeceased him), and thence through his heiress daughter Elizabeth to her husband William de Loundres, and next through their heiress daughter, also Elizabeth, to Sir Christopher Preston, and finally to the Viscounts Gormanston.

Roger Mortimer's childhood came to an abrupt end when Lord Wigmore was mortally wounded in a skirmish near Builth in July 1304. Since Roger was underage at the death of his father, he was placed by King Edward I under the guardianship of Piers Gaveston, 1st Earl of Cornwall, and was knighted by Edward in 1306. Also in that year, Roger was endowed as Baron Wigmore, and came into his full inheritance. His adult life began in earnest.

Military adventures in Ireland and Wales

In 1308 he went to Ireland assisting Gaveston, who was Lord Lord-Lieutenant 1308-1312. In 1314, Roger fought at the Battle of Bannockburn in Scotland. While in Ireland, Roger also secured possession of his large Irish estates. This brought him into conflict with the powerful de Lacy family, who had settled in Ireland after aiding the Norman Conquest. The De Lacys had turned for support to Edward Bruce, brother of Robert Bruce, king of Scotland. In 1315, Edward II appointed Mortimer Lord Lieutenant of Ireland and in 1316, at the head of a large army, he drove Bruce to Carrickfergus and the de Lacys into Connaught, wreaking vengeance on their adherents whenever they were to be found.

He was then occupied for some years with baronial disputes on the Welsh border until about 1318.

Opposition to Edward II

Edward's rule was unpopular with the barons. having inherited debts from his father, he did nothing to improve the realm's finances but wasted money on friends and allies and on his profligate life-style. In 1310, Parliament placed limits on his authority and from 1314 to 1318 Thomas Plantagent more or less governed as Chief Councilor of England. Edward's favorite, Piers Gaveston, was murdered in 1312. In 1318, when Thomas lost popularity due to a defeat in Scotland, Edward, assisted by his new chamberlain and favorite, Hugh Despenser, brushed aside the restrictions on his authority and assumed direct power. As Edward and Hugh seized property illegally, another baronial revolt was soon underway. In 1321, Mortimer joined the growing opposition to Edward II and the Despensers. Again using Parliament, the barons had both Despensers ((Hugh's father was also one of Edward's favorites) exiled then proceeded against the King. Responding robustly, Edward's army crushed the revolt in January, 1322.

Thomas Plantagenet was executed. Mortimer was consigned to the Tower of London, but by drugging the constable, escaped to France, pursued by warrants for his capture, dead or alive, in August 1323.[1] In the following year Queen Isabella, wife of Edward II, anxious to escape from her husband who may have had homosexual affairs but who was not much interested in his wife's company (although they did produce four children, including the future Edward III), obtained his consent to her going to France to use her influence with her brother, King Charles IV, in favor of peace. Her brother had seized Edward's French possessions in 1325. At the French court the queen found Roger Mortimer, who became her lover soon afterward. At his instigation, she refused to return to England so long as the Despensers retained power as the king’s favorites.

Invasion of England and defeat of Edward II

The scandal of Isabella’s relations with Mortimer compelled them both to withdraw from the French court to Flanders, where they obtained assistance for an invasion of England. Landing in England in September 1326, they were joined by Henry, Earl of Lancaster; London rose in support of the queen, and Edward took flight to the west, pursued by Mortimer and Isabella.

After wandering helplessly for some weeks in Wales, the king was taken prisoner on 16 November. Parliament was convened and asked to depose Edward on the grounds that he had broken his coronation oath. At his coronation in 1308, Edward had vowed to "maintain the laws and rightful customs which the community of the realm shall have chosen," as well as to "maintain peace and do justice." The reference to the "community" was an innovation.[2] This was an oath "not simply to maintain the existing law, but to maintain the law as it might develop during the reign."[3] In deposing Edward, Parliament stated that Edward "was incompetent to govern, that he had neglected the business of the kingdom for unbecoming occupations … that he had broken his coronation oath, especially in the matter of doing justice to all, and that he had ruined the realm."[4] Parliament then confirmed Edward's succession.

Though the latter was crowned as Edward III on January 25, 1327, the country was ruled by Mortimer and Isabella, who were widely believed to have arranged the murder of Edward II in the following September at Berkeley Castle. Modern scholarship has cast doubt on this however; it is now almost certain that the ex-king was not buried in 1327, but secretly maintained alive on Mortimer's orders until his fall from grace in 1330.[5].

Powers won and lost

Rich estates and offices of profit and power were now heaped on Mortimer. He was made constable of Wallingford Castle, and in September 1328 he was created Earl of March. However, although in military terms he was far more competent than the Despensers, his ambition troubled many. His own son, Geoffrey, mocked him as "the king of folly." He lived like a king although he "did not enjoy power by right but by duplicity and force."[6] During his short time as ruler of England he took over the lordships of Denbigh, Oswestry, and Clun (all of which previously belonged to the Earl of Arundel). He was also granted the marcher lordship over Montgomery by the Queen. In contrast, during the period from 1314 to 1318, when Thomas Plantaganet had governed, although his critics accused him of favoring his friend, he had upheld the principles of Parliamentary authority.

The jealousy and anger of many nobles was aroused by Mortimer's use of power; Henry, Earl of Lancaster, one of the principals behind Edward II's deposition and a member of the regency council, tried to overthrow Mortimer, but the action was ineffective as the young king passively stood by. Then, in March of 1330, Mortimer ordered the execution of Edmund, Earl of Kent, the half-brother of Edward II who was accused of having aided the deposed king. After this execution Henry Lancaster prevailed upon the young king, Edward III, to assert his independence. In October 1330, a Parliament was called in Nottingham, just days before Edward's eighteenth birthday, and Mortimer and Isabella were seized by Edward and his companions from inside Nottingham Castle. In spite of Isabella’s entreaty to her son, "Fair son, have pity on the gentle Mortimer," Mortimer was conveyed to the Tower.[7]

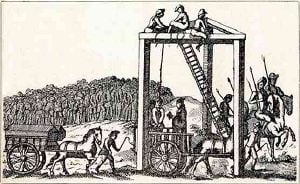

Accused of assuming royal power and of various other high misdemeanors, he was condemned without trial and ignominiously hanged at Tyburn on 29 November 1330, his vast estates being forfeited to the crown. Mortimer's widow, Joan, received a pardon in 1336 and survived till 1356. She was buried beside Mortimer at Wigmore, but the site was later destroyed. Queen Isabella retired to Castle Rising in Norfolk but frequently visited Edward's son's court. It was after her brother's death that Edward III laid claim to the French throne, launching throne of the Hundred Years' War.

In 2002, the actor John Challis, the current owner of the remaining buildings of Wigmore Abbey, invited the BBC program, House Detectives at Large to investigate his property. During the investigation, a document was discovered in which Joan de Geneville petitioned Edward III for the return of her husband's body so she could bury it at Wigmore Abbey. Mortimer's lover, Isabella, had his body buried at Greyfriars, Coventry following his hanging. Edward III replied, "Let his body rest in peace."[8]

Children of Roger and Joan

The marriages of Mortimer's children cemented Mortimer strengths in the West.

- Edmund Mortimer (1302–1331), married Elizabeth de Badlesmere, they had Roger Mortimer, 2nd Earl of March, who was restored to his grandfather’s title.

- Lady Margaret Mortimer (1304–May 5, 1337), married Thomas de Berkeley, 3rd Baron Berkeley

- Maud Mortimer (1307–aft. 1345), married John de Charlton, Lord of Powys[9]

- Geoffrey Mortimer (1309–1372/6)

- John Mortimer (1310–1328)

- Joan Mortimer (c. 1312–1337/51), married James Audley, 2nd Baron Audley

- Isabella Mortimer (c. 1313–aft. 1327)

- Katherine Mortimer (c. 1314–1369), married Thomas de Beauchamp, 11th Earl of Warwick

- Agnes Mortimer (c. 1317–1368), married Laurence Hastings, 1st Earl of Pembroke

- Beatrice Mortimer (c. 1319–1383), married (1) Edward, 2nd Earl of Norfolk; (2) Thomas de Braose, 1st Baron Braose

- Blanche Mortimer (c. 1321–1347), married Peter de Grandison, 2nd Baron Grandison

Legacy

Biographer Ian Mortimer describes Roger Mortimer as the greatest traitor of his age. Not only did he have an adulterous relationship with his Queen but he deposed the king and ruled in his stead for three years, as well as arranging the "judicial murder of the king's uncle, the Duke of Kent." he also "gathered to himself vast estates throughout England and Ireland."[10] Once in power, Mortimer ruled more or less as had the man whom he deposed. Ian Mortimer comments, though, that Mortimer's execution, while one of three that dramatically changed events (Galveston, Plantagenet and Mortimer) was the only one that "brought peace." This is because Edward III proved to be one of England's better kings. Apart from his military achievements, Edwards reign was notable for the evolution of parliamentary governance.

The House of Commons became a more significant body and the office of Speaker was established, consolidating its right to approve new taxes which not only had to be justified but shown to benefit the people. Parliament, in various ways, had plated a vital role in attempts to curb the excesses of Edward II's power. However, during Edward's reign, Parliament and king had been more or less opposed to each other. Under Edward III, Parliament was able to work with the king. Consequently, parliament's own authority developed with the King's approval. Mortimer had used parliament in 1327 as a tool to depose Edward, albeit for good reasons. Unlike Thomas Plantagenet, Mortimer did not respect parliament or the principles of participatory, consultative governance. Yet the constraints on kingly power represented by parliament's deposition of Edward did contribute towards the development of a system in the subjects of the king have a right to oversee his exercise of power. Increasingly, largely due to the reign of the King of whose behalf Mortimer had governed for three years, Parliament would become too strong to be used as anyone's tool. Parliament's interest became the welfare of the whole community.

Notes

- ↑ E.L.G. Stones, The Date of Roger Mortimer's Escape from the Tower of London, The English Historical Review 66 (25) (1951): 897-98.

- ↑ Prestwich (2005), 25.

- ↑ Lyon (2003), 82.

- ↑ Cross (1920), 123.

- ↑ Ian Mortimer, A Note on the Deaths of Edward II. Retrieved November 22, 2008.

- ↑ Mortimer (2006), 219.

- ↑ Mortimer (2006), 238.

- ↑ Locate TV, The House Detectives—Wigmore Abbey. Retrieved November 22, 2008.

- ↑ Charles Hopkinson and Martin Speight, The Mortimers: Lords of the March (Almeley, UK: Logaston Press, 2002), 84-5.

- ↑ Mortimer (2006), 5.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cross, Arthur Lyon. 1920. A Shorter History of England and Greater Britain. London, UK: Macmillan.

- Fryde, Natalie. 1979. The Tyranny and Fall of Edward II: 1321-1326. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521222013.

- Haines, Roy Martin. 2006. King Edward II: Edward of Caernarfon His Life, His Reign, and Its Aftermath 1284-1330. Montreal, CA: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 9780773531574.

- Lyon, Ann. 2003. Constitutional History of the UK. London, UK: Cavendish. ISBN 9781859417461.

- Mortimer, Ian. 2005. "The Death of Edward II in Berkeley Castle." English Historical Review. cxx(489): 1175-1214.

- Mortimer, Ian. 2006. The Greatest Traitor: The Life of Sir Roger Mortimer, Ruler of England, 1327-1330. New York, NY: Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 9780312349417.

- Prestwich, Michael. 2005. Plantagenet England, 1225-1360. The New Oxford History of England. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198228448.

- Weir, Alison. 2005. Isabella, She-Wolf of France. London, UK: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 0224063200.

External links

All links retrieved December 15, 2022.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.