Humphrey Bogart

| Humphrey Bogart | |

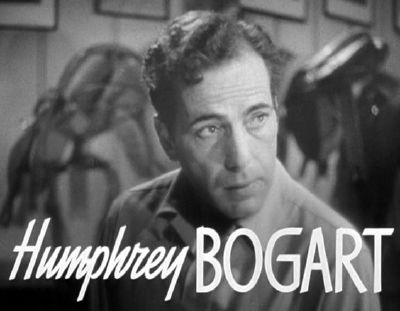

Bogart in a publicity photo, 1945 | |

| Birth name: | Humphrey DeForest Bogart |

|---|---|

| Date of birth: | December 25 1899 |

| Birth location: | New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Date of death: | January 14 1957 (aged 57) |

| Death location: | Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Academy Awards: | Best Actor 1951 The African Queen |

| Spouse: | Helen Menken (1926-1927) Mary Philips (1928-1938) Mayo Methot (1938-1945) Lauren Bacall (1945-1957) |

Humphrey DeForest Bogart (December 25, 1899[1] ‚Äď January 14, 1957) was an Academy Award-winning American actor. In 1999, the American Film Institute named Bogart the Greatest Male Star of All Time. Playing primarily smart, playful and reckless characters anchored by an inner moral code while surrounded by a corrupt world, Bogart's most notable films include The Maltese Falcon (1941), Casablanca (1942), To Have and Have Not (1944), Key Largo (1948), The African Queen (1951) (for which he won an Academy Award for Best Actor), The Caine Mutiny (1954), and The Left Hand of God (1955). Altogether, he appeared in 75 feature motion pictures.

Bogart popularized the "natural" style while creating a film persona of the world-weary tough guy with a heart of gold. Bogart's characters were aware of the corruption in the world and in the human heart, but despite repeated denials, had not given up on his ideals. His cynical exterior was rather a cover to keep his ideals intact. This persona connected with the American viewing public.

Birth and early life

He was born Humphrey DeForest Bogart in New York City, the oldest child of Belmont DeForest Bogart and Maud Humphrey. Belmont was the only child of Adam Welty Bogart (a Canandaigua, New York, innkeeper) and Julia Augusta Stiles, a wealthy heiress. The name "Bogart" derives from the Dutch surname, "Bogaert."[2] Bogart's father was a Presbyterian, of English and Dutch descent, and a descendant of Sarah Rapelje (the first European child born in New Netherland). His mother Maud was an Episcopalian of English heritage, and a descendant of Mayflower passenger John Howland. Bogart was raised in his mother's Episcopal church, but was non-practicing for most of his life.[3]

Bogart's birthday has been a subject of controversy. It was long believed that his birthday on Christmas Day, 1899, was a Warner Bros. fiction created to romanticize his background, and that he was really born on January 23, 1899, a date that appears in many references. However, this story is now considered baseless: although no birth certificate has ever been found, his birth notice did appear in a Boston newspaper in early January 1900, which supports the December 1899 date.

In addition, the 1900 census for the household of Belmont Bogart lists his son Humphrey as having a birth date in December of 1899. There are also three different censuses attesting to his birth date in December, 1899. In addition, his wife, actress Lauren Bacall, always maintained that December 25 was his true birth date, saying that he joked about being cheated out of a present every year.[4]

Childhood

Bogart's father, Belmont, was a successful surgeon. His mother, Maud Humphrey, was a very successful commercial illustrator. Indeed, she used a drawing of baby Humphrey in a well-known advertising campaign for Mellins Baby Food. In her prime, she made over $50,000 a year as an illustrator, at that time a vast sum. The Bogarts lived in a fashionable Upper West Side apartment, and had a cottage in upstate New York.

From his father, Bogart inherited a fondness for fishing and a life-long love of sailing. Humphrey was the oldest of three children; he had two younger sisters: Frances ("Pat") and Catherine Elizabeth ("Kay").[2]

As a boy, Bogart was teased for his curls, his tidiness, the "cute" pictures his mother had him pose for, the Little Lord Fauntleroy clothes she dressed him in‚ÄĒas well as the name "Humphrey."

School

The Bogarts sent their son to the Trinity School in New York and then to the prestigious preparatory school Phillips Academy, in Andover, Massachusetts. They hoped he would go on to Yale, but in 1918, Bogart was expelled from Phillips Academy.[5]

The details of his expulsion are disputed: one story claims that he was expelled for throwing the headmaster (alternatively, a groundskeeper) into Rabbit Pond, a man-made lake on campus. Another cites smoking and drinking, combined with poor academic performance and possibly some intemperate comments to the staff. It has also been said that he was actually withdrawn from the school by his father for failing to improve his academics, as opposed to expulsion.

In spring 1918, Bogart enlisted in the U.S. Navy. It was during his naval stint that he got his trademark scar and developed his characteristic lisp, though the actual circumstances are hazy at best. One account is that his lip was cut by a piece of shrapnel during a shelling of his ship, the USS Leviathan, although some claim that Bogart didn’t make it to sea until after the Armistice was signed. Another version, which Bogart's long time friend, author Nathaniel Benchley, claims is the truth, is that Bogart was injured while on assignment to take a naval prisoner to Portsmouth Naval Prison in New Hampshire. Supposedly, while changing trains in Boston, the handcuffed prisoner asked Bogart for a cigarette and while Bogart looked for a match, the prisoner raised his hands, smashed Bogart across the mouth with his cuffs, cutting Bogart's lip, and fled. The prisoner was eventually taken to Portsmouth. An alternate explanation is that while in the process of uncuffing an inmate, Bogart was struck in the mouth when the inmate wielded one open, uncuffed bracelet while the other side was still on his wrist.[6] Nevertheless, by the time Bogart was treated by a doctor, the scar had already formed. "Goddamn doctor," Bogart later told David Niven, "instead of stitching it up, he screwed it up." In fact, Niven says that when he asked Bogart about his scar he said it was caused by a childhood accident, which seems to contradict the above stories. When actress Louise Brooks met Bogart in 1924, he had scar tissue on his upper lip which he may have had partially repaired before entering the film industry in 1930.[2] Brooks said that his "lip wound gave him no speech impediment, either before or after it was mended."[7]

Early career in the theater

Bogart took odd jobs, joined the Naval Reserve, and eventually drifted into acting. He liked the late hours that actors kept, and enjoyed the attention that an actor got on stage. Most of all, he enjoyed the challenge of putting on a difficult scene, making the audience believe it. He dug deeply into the characters he portrayed, and found them a welcome escape from his own self.

Bogart began his acting career on the Brooklyn stage in 1921, playing a Japanese butler. He never took acting lessons, and had no formal training. An early reviewer wrote of Bogart's work: "To be as kind as possible, we will only say that this actor was inadequate." Bogart loathed the trivial parts he had to play early in his career, calling them "White Pants Willie" roles.

Bogart appeared in 21 Broadway productions between 1922 and 1935. He played juveniles or romantic second-leads in drawing room comedies. He is said to have been the first actor to ask "Tennis, anyone?" on stage.

Early in his career, Bogart met Helen Menken. They married in 1926, divorced in 1927, and remained friends. In 1928, he married Mary Philips. Philips, like Menken, had a fiery temper, and once bit the finger off a police officer who tried to arrest her for drunkenness.

Spencer Tracy was a serious Broadway actor whom Bogart liked and admired, and they became good friends. It was Tracy, in 1930, who first called him "Bogie." (Spelled variously in many sources, Bogart himself spelled his nickname "Bogie.")[8]

The Petrified Forest

In 1934, Bogart starred in the play Invitation to a Murder. The producer Arthur Hopkins saw the play and sent for Bogart when he chose to produce Robert E. Sherwood's new play, The Petrified Forest. Bogart arrived in Hopkins' office while Sherwood was there; Hopkins told him: "I've got a good role for you. A gangster role." Robert Sherwood was sure Hopkins was wrong; Bogart should play the football player. Bogart said later: "They argued back and forth, and I thought Sherwood was right. I couldn't picture myself playing a gangster. So what happened? I made a hit as the gangster."

The Petrified Forest had 197 performances in New York; Bogart played escaped killer Duke Mantee. Leslie Howard, who played the lead, knew how crucial Bogart was to the success of the play. He and Bogart became friends, and he promised to help Bogart reprise his role if Hollywood made the play into a film.

Bogart was proud of his success as an actor, but the fact that it came from playing a gangster weighed on him. He once said, "I can't get in a mild discussion without turning it into an argument. There must be something in my tone of voice, or this arrogant face‚ÄĒsomething that antagonizes everybody. Nobody likes me on sight. I suppose that's why I'm cast as the heavy."

Warner Bros. bought the screen rights to The Petrified Forest, signed up Leslie Howard, then tested several Hollywood veterans for the Duke Mantee role, and chose Edward G. Robinson. Bogart cabled news of this to Howard, who was in Scotland. Leslie Howard insisted that Bogart play Duke Mantee. When Warner Bros. saw that Howard would not budge, they gave in and cast him. Bogart never forgot this favor, and in 1952 he named his only daughter, Leslie, after Leslie Howard, who had died in World War II.

Early film career

Robert E. Sherwood remained a close friend of Bogart's. In 1936, the film version of The Petrified Forest was released. Bogart got excellent reviews, but he was then typecast as a gangster in a series of crime dramas for Warner Bros. All told, Bogart went to the electric chair 12 times, and was sentenced to over 800 years of hard labor. Jack Warner saw nothing wrong with that; as long as the movies made money, and the actors got paid, he saw no reason for anyone to complain.

Mary Philips refused to give up her Broadway career to come to Hollywood with Bogart, and soon they were divorced.

On August 21, 1938, Bogart entered into a disastrous third marriage, with Mayo Methot, a lively, friendly woman when sober, but a paranoid when drunk. She was convinced that her husband was cheating on her. The more she and Bogart drifted apart, the more she drank, got furious and threw things at him: plants, crockery, anything close at hand. Bogart sometimes returned fire, and the press dubbed them "the Battling Bogarts." "The Bogart-Methot marriage was the sequel to the Civil War," said their friend Julius Epstein. A wag observed that there was madness in his Methot. During this time, Bogart bought a sailboat, which he named "Sluggy" after his hot-tempered wife.

In 1938, Warner Bros. put him in a "hillbilly musical" called Swing Your Lady as a wrestling promoter; he later apparently considered this his worst film performance. In 1939, Bogart played a mad scientist in The Return of Doctor X. He cracked: "If it'd been Jack Warner's blood…I wouldn't have minded so much. The trouble was they were drinking mine and I was making this stinking movie."

The studio system, then in its heyday, largely restricted actors to one studio, and Warner Bros. had no interest in making Bogart a star. Shooting on a new movie might begin days or only hours after shooting on the previous one was completed. Any actor who refused a role could be suspended without pay. Bogart didn't like the roles chosen for him, but he worked steadily: between 1936 and 1940, Bogart averaged a movie every two months. He thought that Warner Bros.' wardrobe department was cheap, and often wore his own suits in his movies. In High Sierra, Bogart used his own mutt to play his character's dog, "Pard."

The leading men ahead of Bogart at Warner Bros. included not just such classic stars as James Cagney and Edward G. Robinson, but also actors far less well-known today, such as Victor McLaglen, George Raft and Paul Muni. Most of the studio's better movie scripts went to these men, and Bogart had to take what was left. He made films like Racket Busters, San Quentin, and You Can't Get Away With Murder. The only substantial leading role he got during this period was in Samuel Goldwyn's Dead End (1937), but he played a variety of interesting supporting roles, such as Angels with Dirty Faces (1938) (in which he got shot by James Cagney). Bogart was gunned down on film repeatedly, by Cagney and Edward G. Robinson, among others; he rarely saw his own films and didn't attend the premieres.

Bogart had been raised to believe that acting was beneath a gentleman. Acting in movies was even worse than on the stage, and playing depraved gunmen in "B" pictures for Warner Bros. was not something to be mentioned in polite company.

In California in the 1930s, Bogart bought a 55-foot sailing yacht from Dick Powell. The sea was his sanctuary.[9] He was a serious sailor, respected by other sailors who had seen too many Hollywood actors and their boats. About 30 weekends a year, he went out on his boat. He once said: "An actor needs something to stabilize his personality, something to nail down what he really is, not what he is currently pretending to be."[10]

He had a lifelong disgust for the pretentious, fake or phony, as his son Stephen told Turner Classic Movies host Robert Osborne in 1999. Sensitive yet caustic, and disgusted by the inferior movies he was churning out, Bogart cultivated the persona of a soured idealist, a man exiled from better things in New York, living by his wits, drinking too much, cursed to live out his life among second-rate people and projects.

When he thought an actor, director or a movie studio had done something shoddy, he spoke up about it and was willing to be quoted. The Hollywood press, unaccustomed to candor, was delighted. Bogart once said, "All over Hollywood, they are continually advising me 'Oh, you mustn't say that. That will get you in a lot of trouble' when I remark that some picture or writer or director or producer is no good. I don't get it. If he isn't any good, why can't you say so? If more people would mention it, pretty soon it might start having some effect."[10]

Rise to stardom

High Sierra

High Sierra, a 1941 movie directed by Raoul Walsh, had a screenplay written by Bogart's friend and drinking partner, John Huston, adapted from the novel by W.R. Burnett (author of Little Caesar, among others). The film was a step forward for Bogart. He still played the villain, "Mad Dog" Roy Earle, and he still died at the end, but at least he got to kiss Ida Lupino and play a character with some depth. In a climactic scene, Bogart's character slid 90 feet down a mountainside to his just reward. His stunt double, Buster Wiles, bounced a few times going down the mountain and wanted another take to do better. "Forget it," said Raoul Walsh. "It's good enough for the 25-cent customers."

Bogart and Huston enjoyed each other's company, and drew on each other's gifts. Bogart had always been self-conscious about his height (5'8"); Huston was 6'2" (and his rail-thin build made him appear to be even taller). Bogart had never been close to his father, while Huston was very close to his, actor Walter Huston.

Bogart admired and somewhat envied Huston for his skill as a writer. Though a poor student, Bogart was a lifelong reader. He could quote Plato, Pope, Ralph Waldo Emerson and over a thousand lines of Shakespeare. He admired writers, and some of his best friends were screenwriters, including Louis Bromfield, Nathaniel Benchley and Nunnally Johnson.

John Huston reported becoming easily bored, and admired Bogart not just for his acting talent but for his intense concentration.

The Maltese Falcon

Paul Muni and George Raft had both turned down Bogart's part in High Sierra. Raft then turned down the male lead in John Huston's directorial debut The Maltese Falcon (1941), a cleaned up version of the pre-Production Code The Maltese Falcon (1931); his contract stipulating that he did not have to appear in remakes.

Bogart grabbed the part and audiences saw him play a leading role with real complexity. His character, Sam Spade, was still capable of duplicity and violence, but he was a leading man: handsome, smart, fated to survive. When he discovered his sexy client was a murderess, he turned her in, with the first of several screen speeches for which he would become justly famous: "I don't care who loves who. I won't play the sap for you! You killed Miles and you're going over for it. I hope they don't hang you by your sweet neck. If you're a good girl, you'll be out in 20 years and you'll come back to me. If they hang you, I'll always remember you."

Casablanca

Bogart got his first real romantic lead in Casablanca, playing Rick Blaine, the nightclub owner.

In real life, Bogart himself played tournament chess, one level below master level. It was reportedly his idea that Rick Blaine be portrayed as a chess player.

Off the set, Ingrid Bergman and Bogart hardly spoke during the filming of Casablanca. She said later, "I kissed him but I never knew him." Years later, after Bergman had taken up with Italian director Roberto Rossellini, and bore him a child, Bogart confronted her. "You used to be a great star," he said. "What are you now?" "A happy woman," she replied.

Casablanca won the 1943 Academy Award for Best Picture. Bogart was nominated for the Best Actor in a Leading Role, but lost out to Paul Lukas for his performance in Watch on the Rhine.

Bogart and Bacall

Only Bogart's fourth marriage, to Lauren Bacall ("Baby"), was a happy one. They met while filming To Have and Have Not. The director, Howard Hawks, once commented: "When two people are falling in love with each other, they're not tough to get along with, I can tell you that. Bogie was marvelous. I said, 'You've got to help,' and of course after a few days he really began to get interested in the girl. That made him help more." Hawks at some point began to disapprove of the pair. He fell for Bacall as well, and wanted her to feel the same way (although he was married). Out of jealousy, he said of Bacall: "She had to keep practicing for six to eight months to keep that low voice. Now, it's perfectly natural. And the funny thing is that Bogie fell in love with the character she played, so she had to keep playing it the rest of her life." They were married on May 21, 1945 in Lucas, Ohio, at Malabar Farm, the country home of Pulitzer Prize-winning author Louis Bromfield, who was a close friend of Bogart's. The wedding was held in the Big House.

Bogart and Bacall's relationship is at the heart of the film noir masterpiece The Big Sleep. Raymond Chandler thoroughly admired Bogart's performance: "Bogart can be tough without a gun. Also, he has a sense of humor that contains that grating undertone of contempt."

Bacall allowed Bogart lots of weekend time on his boat. She got seasick, and Bogart said, "The trouble with having dames on board is you can't pee over the side." Bogart would frequently sail to Catalina with friends or set some lobster traps.

Bacall wrote of Bogart: "You had to stay awake married to him. Every time I thought I could relax and do everything I wanted, he'd buck. There was no way to predict his reactions, no matter how well I knew him."

Bogart and Bacall moved into a $160,000 white brick mansion in Holmby Hills, an exclusive neighborhood between Beverly Hills and Bel-Air. Bogart and Bacall had two Jaguar cars, and three blooded Boxer dogs. Bogart said "We moved where all the creeps live." But he liked some of his neighbors, especially Judy Garland.

On January 6, 1949, Lauren Bacall gave birth to a son, Stephen Humphrey Bogart, making Bogart a father at 49. He had had months to absorb the news and even had his own baby shower. (Frank Sinatra brought him baby rattles.) On August 23, 1952, they had their second child, Leslie Howard Bogart (a girl named after British actor Leslie Howard, who had been killed in World War II).

Bogart Stories

The panda case

In 1950, Bogart and his friend Bill Seeman arrived at the El Morocco Club in New York after midnight. Bogart and Seeman sent someone to buy two 22-pound stuffed pandas because, in a drunken state, they thought the pandas would be good company.[11] They propped up the bears in separate chairs, and began to drink.

Two young women at the club saw the stuffed animals, and one of the women picked up one of the pandas. She quickly ended up on the floor. The other woman tried to do the same and wound up in the same position.[11] Club spokesperson Leonard MacBain later stated, "No blows were exchanged, it was just one of those things."[11] The next morning Bogart was awakened by a city official who served him an assault summons. Knowing a media frenzy was imminent, he met the media still unshaven and in his pajamas. He told the press that he remembered grabbing the panda and "this screaming, squawking young lady. Nobody got hurt, I didn't sock anybody; if girls were falling on the floor, I guess it was because they couldn't stand up."[12] At the same time Time reported that the alleged victim had three marks from the alleged assault and "she explained that they were swelling and contusions."[11]

That following Friday, Bogart went to court to face the charges. After the woman admitted to touching the panda, "Magistrate John R. Starkey ruled that Bogart had been defending his property, said he suspected the actor had been mousetrapped in the cause of club publicity, and dismissed the case."[13]

The Rat Pack and Romanoff's

Bogart was a founding member of the Rat Pack. During the spring of 1955, after a long party in Las Vegas with Frank Sinatra, Mike and Gloria Romanoff, Angie Dickinson and others, "Lauren Bacall surveyed the wreckage of the party" and declared, "You look like a god damn rat pack."[14]

Romanoff's in Beverly Hills was where the Rat Pack became "official." "Sinatra was named Pack Leader. Betty [Bacall] was named Den Mother, Bogie was Director of Public Relations, and Sid Luft was Acting Cage Manager."[13] When asked by columnist Earl Wilson what the purpose of the group was, Bacall responded "to drink a lot of bourbon and stay up late."[14]

Even so, the Rat Pack under Bogart's presidency was pretty civilized compared to what it became later. Bogart actually got away with telling Sinatra that he had an immature attitude towards women.

Later career

The enormous success of Casablanca redefined Bogart's career. For the first time, Bogart could be cast successfully as a tough, strong man and, at the same time, as a vulnerable love interest. From 1943 to 1955, Bogart starred in many other films that reflected his diverse talent as an actor. In addition to being offered better, more diverse roles, he started his own production company in 1949 called Santana Productions, named after his private sailing yacht. Under Bogart's Santana Productions, Bogart starred in:

- Knock on Any Door (1949)

- Tokyo Joe (1949)

- In a Lonely Place (1950)

- Sirocco (1951)

- Beat the Devil (1954)

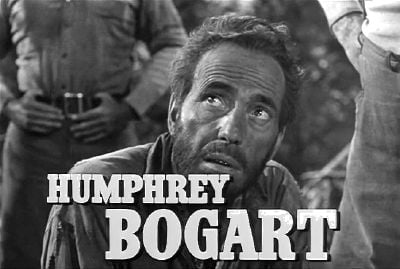

The African Queen

In 1951, Bogart starred in the movie The African Queen, with Katharine Hepburn, again directed by his friend John Huston. It was a difficult shoot, on location in Africa and just about everyone in the cast came down with dysentery except Bogart and John Huston. Bogart explained: "I built a solid wall of Scotch between me and the bugs. If a mosquito bit me, he'd fall over dead drunk."

One day during The African Queen shoot, the eponymous boat even sank. Lauren Bacall recalled: "The natives had been told to watch it and they did; they watched it sink."

John Huston recalled: "Bogie didn't particularly care for the Charlie Alnutt role when he started, but I slowly got him into it, showing him by expression and gesture what I thought Alnutt should be like. He first imitated me, then all at once he got under the skin of that wretched, sleazy, absurd, brave little man. He realized he was on to something new and good. He said to me, 'John, don't let me lose it.'"

Hepburn's proper spinster character scolded Bogart's Charlie Alnutt: "Nature, Mr. Alnutt, is what we are put in this world to rise above." Bogart had a famous put down too: "You crazy, psalm-singing, skinny old maid!"

The African Queen was the first Technicolor film in which Bogart appeared. Remarkably, he appeared in relatively few color films during the rest of his career, which continued for another five years. (His other color films included The Caine Mutiny, The Barefoot Contessa, We're No Angels, and The Left Hand of God.)

The role of Charlie Alnutt won Bogart his only Academy Award for Best Actor in a Leading Role in 1951. He had vowed to friends that if he won, his speech would break the convention of thanking everyone in sight. He would say instead: "I don't owe anything to anyone! I earned this award by hard work and paying attention to my craft." But when Bogart won the Academy Award, he thanked John Huston, Katharine Hepburn, and the cast and crew.

Also in 1951, Bogart and Bacall co-starred in the syndicated radio drama Bold Venture, for which he was paid a reported $4,000 a week. He played a character very much like Steve in To Have and Have Not, and she played his "ward." He called her "Sailor."

The House Un-American Activities Committee

Bogart organized a delegation to Washington, D.C., during the height of McCarthyism, against the House Un-American Activities Committee's harassment of Hollywood writers and actors. He subsequently wrote an article "I'm no communist" in the May 1948 edition of Photoplay in which he distanced himself from the Hollywood Ten in order to counter the negative publicity that resulted from his appearance.[15]

Final roles

He dropped his asking price to get the role of Captain Queeg in Edward Dmytryk's The Caine Mutiny, then griped with some of his old bitterness about it. ("This never happens to Cooper or Grant or Gable, but always to me. Why does it happen to me?")

Bogart gave a bravura performance as Captain Queeg, in many ways an extension of the character he had played in The Maltese Falcon, Casablanca, and The Big Sleep‚ÄĒthe wary loner who trusts no one‚ÄĒbut with none of the warmth or humor that made those characters so appealing. Like his portrayal of Fred C. Dobbs in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, Bogart played a paranoid, self-pitying character whose small-mindedness eventually destroyed him.

Sabrina (dir. Billy Wilder) and The Barefoot Contessa (dir. Joseph Mankiewicz) in 1954 gave him two of his subtlest roles. During the filming of The Left Hand of God (1955) he noticed his co-star Gene Tierney was having a hard time remembering her lines and was also behaving oddly. He coached Tierney, feeding her lines. He was familiar with mental illness (his sister had bouts of depression), and Bogart encouraged Tierney to seek treatment.

In 1955, he made three films: We're No Angels (dir. Michael Curtiz), The Left Hand of God (dir. Edward Dmytryk) and The Desperate Hours (dir. William Wyler). Mark Robson's The Harder They Fall (released in 1956) was his last film.

Television work

Bogart rarely appeared on television. However, he and his wife appeared on news journalist Edward R. Murrow's Person to Person. Bogart was also featured on The Jack Benny Show. Bogart and Bacall worked together on a rare color telecast, in 1955, an NBC adaptation of The Petrified Forest for the Producer's Showcase. Only a black and white kinescope of the live telecast has survived.

Death

By the mid-1950s, Bogart's health was failing. Once, after signing a long-term deal with Warner Bros., Bogart predicted with glee that his teeth and hair would fall out before the contract ended. That sent a fuming Jack Warner to his lawyers.

Bogart, a heavy smoker and drinker, contracted cancer of the esophagus. He almost never spoke of it and refused to see a doctor until January of 1956, and by then surgery on his esophagus, two lymph nodes and a rib was too little, too late.

Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy came to see him. Bogart was too weak to walk up and down stairs. He tried to joke about it: "Put me in the dumbwaiter and I'll ride down to the first floor in style."

Hepburn has described the last time she and Spencer Tracy saw Bogart (the night before he died): "Spence patted him on the shoulder and said, 'Goodnight, Bogie.' Bogie turned his eyes to Spence very quietly and with a sweet smile covered Spence's hand with his own and said, 'Goodbye, Spence.' Spence's heart stood still. He understood."[16]

Bogart had just turned 57 and weighed only 80 pounds (36 kg) when he died on January 14, 1957 after falling into a coma. He died at 2:25 a.m. at his home at 232 Mapleton Drive in Holmby Hills, California, nearby Hollywood. His funeral was held at All Saints Episcopal Church with musical selections played from Bogart's favorite composers, Johann Sebastian Bach and Claude Debussy. Bacall had asked Spencer Tracy to give the eulogy but Tracy was too upset. John Huston gave the eulogy instead, and reminded the gathered mourners that while Bogart's life had ended far too soon, it had been a rich one. Huston said: "He is quite irreplaceable. There will never be another like him."[17]

Huston described Bogart:

Himself, he never took too seriously‚ÄĒhis work most seriously. He regarded the somewhat gaudy figure of Bogart, the star, with an amused cynicism; Bogart, the actor, he held in deep respect‚ĶIn each of the fountains at Versailles there is a pike which keeps all the carp active; otherwise they would grow overfat and die. Bogie took rare delight in performing a similar duty in the fountains of Hollywood. Yet his victims seldom bore him any malice, and when they did, not for long. His shafts were fashioned only to stick into the outer layer of complacency, and not to penetrate through to the regions of the spirit where real injuries are done.[17]

Katharine Hepburn said:

He was one of the biggest guys I ever met. He walked straight down the center of the road. No maybes. Yes or no. He liked to drink. He drank. He liked to sail a boat. He sailed a boat. He was an actor. He was happy and proud to be an actor. He'd say to me, 'Are you comfortable? Everything okay?' He was looking out for me.[18]

His cremated remains are interred in Forest Lawn Memorial Park Cemetery, Glendale, California. Buried with him is a small gold whistle, which he had given to his future wife, Lauren Bacall, before they married. In reference to their first movie together, it was inscribed: "If you want anything, just whistle."

Humphrey Bogart's hand and foot prints are immortalized in the forecourt of Grauman's Chinese Theater and he has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6322 Hollywood Boulevard in Hollywood.

After his death, the "Bogie Cult" formed at the Brattle Theatre which contributed to his spike in popularity in the late 1950s and 1960s.

Legacy

Though he started his career as Broadway stage player and B-movie actor during the 1920s and 1930s, Bogart's later accomplishments have made him a worldwide film icon. French actors, such as Jean-Paul Belmondo, were deeply influenced by his work and image. India’s great national movie star, Ashok Kumar, listed Bogart as a major influence on his "natural" acting style. In the United States, Bogart is remembered in one of Woody Allen’s comic movies, Play It Again, Sam, which relates the story of a young man obsessed by his persona. In 1997, the United States Postal Service featured Bogart in its "Legends of Hollywood" series, and Entertainment Weekly magazine has named Bogart the number one movie legend of all time. Bogart perfected the role of the "tough guy" character, world-weary and full of sardonic wit, but who nevertheless underneath had a "heart of gold."

Quotes

Attributed

- "I can't say I ever loved my mother, I admired her."

- "My parents fought. We kids would pull the covers over our ears to keep out the sound of fighting. Our home was kept together for the sake of the children as well as for the sake of propriety."

- "I don't approve of the John Waynes and the Gary Coopers saying 'Shucks, I ain't no actor‚ÄĒI'm just a bridge builder or a gas station attendant.' If they aren't actors, what the hell are they getting paid for? I have respect for my profession. I worked hard at it."

- "The whole world is three drinks behind."

- "Don't ever name a restaurant after me."

Famous movie quotes

Casablanca

- "I stick my neck out for nobody."

- "There are certain sections of New York, Major, that I wouldn't advise you to try to invade." [to Major Strasser]

- "You played it for her, you can play it for me! … If she can stand it, I can! Play it!"

- "Of all the gin joints in all the towns in all the world, she walks into mine."

- "Here's looking at you, kid."

- "Tell me, who was it you left me for? Was it Laszlo, or were there others in between? Or‚ÄĒaren't you the kind that tells?"

- "Don't you sometimes wonder if it's worth all this? I mean what you're fighting for."

- "If that plane leaves the ground and you're not with him, you'll regret it. Maybe not today, maybe not tomorrow, but someday soon; and for the rest of your life."

- "I'm no good at being noble, but it doesn't take much to see that the problems of three little people don't amount to a hill of beans in this crazy mixed up world. Someday you'll understand that."

- "Louis, I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship."

- "We'll always have Paris."

The Maltese Falcon

- "The stuff that dreams are made of." [about the falcon - a misquotation from Shakespeare's The Tempest, Act IV Scene 1 - ‚ÄĚWe are such stuff as dreams are made on, and our little life is rounded with a sleep.‚ÄĚ ]

- "When you're slapped, you'll take it and like it." [to Peter Lorre]

- "The cheaper the crook, the gaudier the patter." [to the "Gunsel"] (played by Elisha Cook, Jr.)

- "I don't mind a reasonable amount of trouble." [to Brigid (Mary Astor)]

- "You're good, you're very good."

The Big Sleep

- "Such a lot of guns around town and so few brains!"

Films

1928‚Äď1940

| Year | Film | Role | Director |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1928 | The Dancing Town | Man in Doorway at Dance | Edmund Lawrence |

| 1930 | Broadway's Like That | Ruth's Fiance | Arthur Hurley |

| Up the River | Steve Jordan | John Ford | |

| A Devil with Women | Tom Standish | Irving Cummings | |

| 1931 | Body and Soul | Jim Watson | Alfred Santell |

| The Bad Sister | Valentine Corliss | Hobart Henley | |

| A Holy Terror | Steve Nash | Irving Cummings | |

| Women of All Nations | Stone (scenes deleted) | Raoul Walsh | |

| 1932 | Love Affair | Jim Leonard | Thornton Freeland |

| Big City Blues | Shep Adkins | Mervyn LeRoy | |

| Three on a Match | Harve | Mervyn LeRoy | |

| 1934 | Midnight | Garboni | Chester Erskine |

| 1936 | The Petrified Forest | Duke Mantee | Archie Mayo |

| Bullets or Ballots | Nick "Bugs" Fenner | William Keighley | |

| Two Against the World | Sherry Scott | William C. McGann | |

| China Clipper | Hap Stuart | Ray Enright | |

| Isle of Fury | Valentine "Val" Stevens | Frank McDonald | |

| 1937 | Black Legion | Frank Taylor | Archie Mayo |

| The Great O'Malley | John Phillips | William Dieterle | |

| Marked Woman | David Graham | Lloyd Bacon | |

| Kid Galahad | Turkey Morgan | Michael Curtiz | |

| San Quentin | Joe "Red" Kennedy | Lloyd Bacon | |

| Dead End | Hugh "Baby Face" Martin | William Wyler | |

| Stand-In | Doug Quintain | Tay Garnett | |

| 1938 | Swing Your Lady | Ed Hatch | Ray Enright |

| Crime School | Deputy Commissioner Mark Braden | Lewis Seiler | |

| Men Are Such Fools | Harry Galleon | Busby Berkeley | |

| Racket Busters | Pete "Czar" Martin | Lloyd Bacon | |

| The Amazing Dr. Clitterhouse | "Rocks" Valentine | Anatole Litvak | |

| Angels with Dirty Faces | James Frazier | Michael Curtiz | |

| Swingtime in the Movies | Himself | Crane Wilbur | |

| 1939 | King of the Underworld | Joe Gurney | Lewis Seiler |

| The Oklahoma Kid | Whip McCord | Lloyd Bacon | |

| You Can't Get Away with Murder | Frank Wilson | Lewis Seiler | |

| Dark Victory | Michael O'Leary | Edmund Goulding | |

| The Roaring Twenties | George Hally | Raoul Walsh | |

| The Return of Doctor X | Dr. Maurice Xavier, aka Marshall Quesne | Vincent Sherman | |

| Invisible Stripes | Chuck Martin | Lloyd Bacon | |

| 1940 | Virginia City | John Murrell | Michael Curtiz |

| It All Came True | Grasselli aka Chips Maguire | Lewis Seiler | |

| Brother Orchid | Jack Buck | Lloyd Bacon | |

| They Drive by Night | Paul Fabrini | Raoul Walsh |

1941‚Äď1950

| Year | Film | Role | Director | Leading Lady |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1941 | High Sierra | Roy Earle | Raoul Walsh | Ida Lupino |

| The Wagons Roll at Night | Nick Coster | Ray Enright | Sylvia Sidney | |

| The Maltese Falcon | Sam Spade | John Huston | Mary Astor | |

| All Through the Night | Gloves Donahue | Vincent Sherman | Kaaren Verne | |

| 1942 | The Big Shot | Joseph "Duke" Berne | Lewis Seiler | Irene Manning |

| Across the Pacific | Rick Leland | John Huston | Mary Astor | |

| Casablanca | Rick Blaine | Michael Curtiz | Ingrid Bergman | |

| 1943 | Action in the North Atlantic | Lt. Joe Rossi | Lloyd Bacon | Julie Bishop |

| Sahara | Sgt. Joe Gunn | Zoltan Korda | ||

| Thank Your Lucky Stars | Himself | David Butler | ||

| 1944 | Passage to Marseille | Jean Matrac | Michael Curtiz | Michele Morgan |

| To Have and Have Not | Harry "Steve" Morgan | Howard Hawks | Lauren Bacall | |

| I Am an American[19] | Himself | Crane Wilbur | ||

| 1945 | Conflict | Richard Mason | Curtis Bernhardt | Alexis Smith |

| 1946 | The Big Sleep | Philip Marlowe | Howard Hawks | Lauren Bacall |

| Two Guys From Milwaukee | Himself | David Butler | ||

| 1947 | Dead Reckoning | Capt. "Rip" Murdock | John Cromwell | Lizabeth Scott |

| The Two Mrs. Carrolls | Geoffrey Carroll | Peter Godfrey | Barbara Stanwyck | |

| Dark Passage | Vincent Parry | Delmer Daves | Lauren Bacall | |

| 1948 | The Treasure of the Sierra Madre | Fred C. Dobbs | John Huston | |

| Key Largo | Frank McCloud | John Huston | Lauren Bacall | |

| Always Together | Himself | Frederick De Cordova | ||

| 1949 | Knock on Any Door | Andrew Morton | Nicholas Ray | |

| Tokyo Joe | Joseph "Joe" Barrett | Stuart Heisler | Florence Marly | |

| 1950 | Chain Lightning | Lt. Col. Matthew "Matt" Brennan | Stuart Heisler | Eleanor Parker |

| In a Lonely Place | Dixon Steele | Nicholas Ray | Gloria Grahame |

1951‚Äď1956

| Year | Film | Role | Director | Leading Lady |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1951 | The Enforcer | Dist. Atty. Martin Ferguson | Bretaigne Windust | |

| Sirocco | Harry Smith | Curtis Bernhardt | Marta Toren | |

| The African Queen | Charlie Allnut | John Huston | Katharine Hepburn | |

| 1952 | Deadline ‚ÄĒ U.S.A. | Ed Hutcheson | Richard Brooks | Kim Hunter |

| 1953 | The Road to Bali | Himself | Hal Walker | |

| Battle Circus | Maj. Jed Webbe | Richard Brooks | June Allyson | |

| Beat the Devil | Billy Dannreuther | John Huston | Jennifer Jones, Gina Lollobrigida | |

| 1954 | The Caine Mutiny | Lt. Cmdr. Philip Francis Queeg | Edward Dmytryk | |

| Sabrina | Linus Larrabee | Billy Wilder | Audrey Hepburn | |

| The Barefoot Contessa | Harry Dawes | Joseph L. Mankiewicz | Ava Gardner | |

| 1955 | We're No Angels | Joseph | Michael Curtiz | |

| The Left Hand of God | James "Jim" Carmody | Edward Dmytryk | Gene Tierney | |

| The Desperate Hours | Glenn Griffin | William Wyler | ||

| 1956 | The Harder They Fall | Eddie Willis | Mark Robson | Jan Sterling |

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ David Mikkelson, Was Humphrey Bogart Born on Christmas Day? Snopes, December 20, 1999. Retrieved May 7, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Jeffrey Meyers, Bogart: A Life in Hollywood (London: Andre Deutsch Ltd., 1997, ISBN 0233991441).

- ‚ÜĎ Stephen Humphrey Bogart, Bogart: In Search of My Father (New York: Dutton, 1995, ISBN 0525939873).

- ‚ÜĎ Lauren Bacall, By Myself (New York: Alfred Knopf, 1978, ISBN 978-0224016926).

- ‚ÜĎ David Wallechinsky and Amy Wallace, The New Book of Lists: The Original Compendium of Curious Information (New York: Canongate, 2005, ISBN 1841957194), 9.

- ‚ÜĎ Joseph A. Citro, Weird New England: Your Travel Guide to New England's Local Legends and Best Kept Secrets (New York: Sterling, 2005, ISBN 1402733305), 240-241.

- ‚ÜĎ Allen Eyles, Bogart (Macmillan, 1975, ISBN 978-0333180204).

- ‚ÜĎ letter from Bogart to John Huston displayed in documentary John Huston: The Man, the Movies, the Maverick (1989).

- ‚ÜĎ Interview with John Huston

- ‚ÜĎ 10.0 10.1 Humphrey Bogart Biography Biography Base. Retrieved May 9, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 A. M. Sperber and Eric Lax, Humphrey Bogart (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1997, ISBN 0688075398), 428.

- ‚ÜĎ Sperber and Lax, 429.

- ‚ÜĎ 13.0 13.1 Sperber and Lax, 430.

- ‚ÜĎ 14.0 14.1 Sperber and Lax, 504.

- ‚ÜĎ Humphrey Bogart, "I'm no communist" Photoplay, May 1948. Retrieved May 7, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ Humphrey Bogart Timeline Twoop Timelines.

- ‚ÜĎ 17.0 17.1 John Laudun, John Huston‚Äôs eulogy for Humphrey Bogart Huston on Bogart. Retrieved May 9, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ Stefan Kanfer, Tough Without a Gun: The Life and Extraordinary Afterlife of Humphrey Bogart (Vintage, 2012, ISBN 978-0307455819).

- ‚ÜĎ The 16 minute film, I Am an American, was featured in American theaters as a short feature in connection with "I Am an American Day" (now called Constitution Day). I Am an American was produced by Gordon Hollingshead, also written by Crane Wilbur. Besides Bogart, it featured Gary Gray, Dick Haymes, Danny Kaye, Joan Leslie, Dennis Morgan, Knute Rockne, and Jay Silverheels.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bacall, Lauren. By Myself. New York: Alfred Knopf, 1978. ISBN 978-0224016926

- Bogart, Stephen Humphrey. Bogart: In Search of My Father New York: Dutton, 1995. ISBN 0525939873

- Citro, Joseph A. Weird New England: Your Travel Guide to New England's Local Legends and Best Kept Secrets. New York: Sterling, 2005. ISBN 1402733305

- Eyles, Allen. Bogart Macmillan, 1975. ISBN 978-0333180204

- Halliwell, Leslie.Halliwell's Film, Video and DVD Guide. New York: Harper Collins Entertainment, 2004. ISBN 0007190816

- Hepburn, Katharine. The Making of the African Queen. New York: Alfred Knopf, 1987. ISBN 0394562720

- Hill, Jonathan and Jonah Ruddy. Bogart: The Man and the Legend. London: Mayflower-Dell, 1966.

- Kanfer, Stefan. Tough Without a Gun: The Life and Extraordinary Afterlife of Humphrey Bogart. Vintage, 2012. ISBN 978-0307455819

- Meyers, Jeffrey. Bogart: A Life in Hollywood. London: Andre Deutsch Ltd., 1997. ISBN 0233991441

- Michael, Paul. Humphrey Bogart: The Man and his Films. New York: Bananza Books, 1965.

- Porter, Darwin. The Secret Life of Humphrey Bogart: The Early Years (1899-1931). New York: Georgia Literary Association, 2003. ISBN 0966803051

- Pym, John (ed.). "Time Out" Film Guide. Time Out Group Ltd., 2004. ISBN 1904978215

- Sperber, A.M. and Eric Lax. Bogart. New York: William Morrow & Co., 1997. ISBN 0688075398

- Wallechinsky, David, and Amy Wallace. The New Book of Lists: The Original Compendium of Curious Information, New York: Canongate, 2005. ISBN 1841957194

- Youngkin, Stephen D. The Lost One: A Life of Peter Lorre. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 2005. ISBN 0813123607

External links

All links retrieved July 19, 2024.

- Humphrey Bogart Internet Movie Database

- Humphrey Bogart TCM Movie Database

- Humphrey Bogart at the Internet Broadway Database

- Humphrey Bogart Chess Games.

- Genealogy of Humphrey Bogart

- The Lost One: A Life of Peter Lorre Contains a full chapter on the personal and professional friendship between Bogart and classic film actor Peter Lorre.

| |||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.