Illusion

Illusions are distortions of a sensory perception, revealing how the brain normally organizes and interprets sensory stimulation. Illusions can occur with each of the human senses, but visual illusions are the most well known and understood. The emphasis on visual illusions occurs because vision often dominates the other senses. Some illusions occur because of biological sensory structures within the human body or conditions outside of the body within one’s physical environment. Other illusions are based on general assumptions the brain makes during perception. These assumptions are made using organizational principles, such as an individual's depth perception and motion perception, and perceptual constancy that are part of our psychological ability.

Most illusions occur in people of all cultures and environmental experiences, indicating that they reflect universals in human perception. Research in illusions therefore seeks to understand how human beings perceive the environment through specific rules of perceptual construction.

Illusions are also a source of fascination, commonly used by artists. In many cases two-dimensional art gains the appearance of the third dimension through the use of techniques based on principles revealed in illusions. One of the most notable uses of such principles is found in the trompe d'oeil technique. Other artists deliberately use illusion to entertain the observer by creating impossible figures. The continued development of such techniques, and the fascination they have for the viewer, reflect both the endless creativity and the appreciation for creativity that are to be found in human nature.

Definition

Illusion is from Middle English, from Anglo-French, from Latin illusio the action of mocking, from illudere to mock at, from in + ludere to play, mock.

The Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary defines "illusion" as:

- the state or fact of being intellectually deceived or misled; an instance of such deception

- a misleading image presented to the vision; something that deceives or misleads intellectually; perception of something objectively existing in such a way as to cause misinterpretation of its actual nature; a pattern capable of reversible perspective.

Thus, illusions are distortions of sensory perception, mocking or tricking our senses so that we are deceived. While illusions distort reality, they are generally shared by most people.[1] As a result, illusions have been utilized by artists to make their pictures appear three-dimensional or to produce special effects, as well as being a valuable source of information for those studying how we process information from the world.

Unlike hallucinations, which are sensory experiences in the absence of stimuli, an illusion describes a misinterpretation of a true sensation so it is perceived in a distorted manner. For example, hearing voices regardless of the environment would be hallucination, whereas hearing voices in the sound of running water (or other auditory source) would be an illusion.

Research on illusions

Overall, the understanding of illusions has become a pursuit of sensory psychologists who are exploring the ways the brain processes sensory information. By understanding the ways in which a brain misperceives stimuli, it is possible to gain a better understanding of the rudimentary principles and schemas through which the brain routinely processes information. This information also has practical value, especially in advancing research and development of robotics and artificial intelligence. For example, the dynamism of the visual system, which allows humans to recognize and discern objects from multiple perspectives, has yet to be achieved in robotics.

Illusions occur with all five of our physical senses, but visual illusions are the most common, well-known, and well researched.

Visual illusions

Vision is continuously engaged in daily life. Though the world is perceived as seamless, images and motions imperceptibly blending into the next, it is only so because of the continual, visual updates that the eyes relay to the brain on a time scale so rapid that a break in vision is never perceived. The collaboration of photo-receptors, ganglion cells, receptive fields, and the brain creates the perception of colors, seamless motion, contrast, and quality such that the efficiency and completeness of vision is unparalleled in comparison with any piece of apparatus or instrumentation yet invented.[2]

The study of the visual system often involves artificially manipulating visual stimuli specifically created to cause mis-perception of a visual scene. A conventional assumption is that there are naturally occurring physiological illusions and cognitive illusions that are demonstrated through manipulations and expose the mechanisms of human perception.

The existence of optical illusions underlines the adaptations the brain has made in order to operate at the speed it does in perceiving and translating visual stimuli. Though the term "optical illusions" itself sounds pejorative, as if describing some malfunction, they actually reveal the various essential adaptations that are either hard-wired or well established in the brain. Several well-known visual illusions are described below.

Rubin Vase - This illusion displays an aspect of perceptual organization, figure-ground perception, in which the brain is attempting to assign one shape as the figure on top of a background based on contrast. There is considerable flexibility, as the brain can interpret the figure-ground illusion as a white vase in front of a black background, and almost as simultaneously interpret the illusion as two, silhouetted faces facing each other over a white background. This illusion was made famous by Danish psychologist Edgar Rubin in 1915.

Kanizsa Triangle - First described by the Italian psychologist Gaetano Kanizsa in 1955, this famous illusion contains a white, equilateral triangle that seems to be obscuring three, black circles and the outline of another equilateral triangle. However, the white triangle is nonexistent. This effect is known as a "subjective" or "illusory" contour and is a product of a process known as "modal completion." Also, the nonexistent white triangle often appears to be brighter than the surrounding area, even though both the "triangle" and background are of the same brightness.

Ponzo Illusion - Illusions can be based on an individual's ability to see in three dimensions even through the image hitting the retina is only two dimensional. The Ponzo Illusion, revealed by Mario Ponzo in 1913, is an example of an illusion which uses monocular cues of depth perception to fool the eye. In the Ponzo illusion the converging parallel lines suggest to the brain that the image higher in the visual field is further away due to perspective. The brain therefore perceives it to be larger, though the two images hitting the retina are actually the same size.

Phi Phenomenon - In his Experimental Studies on the Seeing of Motion, Max Wertheimer described a perceptual illusion involving a succession of still images that created the illusion of apparent motion. The classic phi phenomenon experiment involves two images. The first image depicts a line on the left side of the frame. The second image depicts a line on the right side of the frame. The images are projected in succession at different combinations of time and space between the two lines, and at a certain combination, viewers will perceive a sensation of motion in the space around the two lines. This is not to be confused with perceiving continuous motion of objects, a motion that Wertheimer called "beta" movement.

Beta movement can often be seen in blinking Christmas lights or the lights that border movie marquees. The example shows how blinking lights can give the appearance of movement, despite the fact that each light is simply turning on and off at a regular interval.

Understanding visual illusions

The study of illusions has focused on the visual system due to the prevalence and diversity of optical illusions. Our visual system faces a challenging task, attempting to correctly represent reality while calculating and perceiving various factors, such as light, color, texture, and size in a three-dimensional environment. Visual perception is created by our brain's interpretation of visual information and sometimes it results in fascinating visual illusions. Our mind gets "actively" involved in interpreting the perceptual input rather than passively recording the input, though it does not always accurately represent that input.

Physical illusions

Physical illusions are optical illusions in which the illusion has occurred due to the physical properties of the environment and their effects on the behavior of light, essentially occurring before light hits the retina of the eye. The following are some examples.

- The mirage phenomena is an optical illusion often associated with the illusory oasis in the middle of a desert, caused by the reflection of light off a thin layer of hot air near heated ground (known as a temperature inversion). In deserts, the reflection of the sky off this layer of air may give the illusion of a lake in the distance.

- The antisolar rays effect occurs because of the scattering of sunlight, obstructions, and perspective. While solar rays occur when an obstruction of the sun reveals rays of light radiating from the sun's position, anti-solar rays are often seen converging on the horizon point opposite of the sun (towards the shadow of one's head), even though in both cases the sun's physical rays are parallel to each other due to its size and distance from the earth.

- A rainbow is an apparent object, having shape and color, but no definitive location. Its appearance and location depend on the viewer's position relative to the sun and water molecules in the air.

- Reflection is caused by light bouncing off an object. In the case of a mirror, it creates the illusion of another object or person being present.[3]

- Refraction is the bending of light rays that occurs when light enters another medium of different density (for example, from air to water) at an angle. The change in density causes a change in the speed of the light rays, which can create a visual distortion, such as the bent appearance of a straw in a glass of water.

Physiological illusions

Physiological illusions, such as the afterimages following bright lights or adapting stimuli of excessively longer alternating patterns (contingent perceptual aftereffect, CAE), are the effects on the eyes or brain of excessive stimulation of a specific type - brightness, tilt, color, movement, and so on.[3] The explanation of these effects is that stimuli have individual dedicated neural paths or channels in the visual cortex, the repetitive stimulating of which can mislead the visual system.

- Blind spots occur as a result of the eye's anatomy and physiology. The various receptive fields of the eye's ganglions gather at a certain point to exit the eye as the optic nerve. Thus, there are no photoreceptors in that region of the eye and no image is produced even though light may fall there. The blind spot in either eye is, however, unnoticeable due to the compensatory visual field of the other.

- Afterimages are the result of fatigued visual channels and persistence of vision (such as in animation and cinema). In general, when the cones of an eye's retina are exposed to a certain wavelength of light (color), they adapt and lose sensitivity; the eye prevents this through small, rapid eyes movements. However, if a cone sensitive to a certain color (say, red) remains exposed on that color, whether on purpose or because the area of color is larger than the eye movements, diverting the eyes to a blank space will reveal the afterimage. This occurs because other parts of the retina not sensitive to the particular color are still active. The result is the inverse, or complement, of the original image/color.

- Illusions concerning contrast and color are mostly due to the way the retina's rods and cones process information through their receptive fields.

Cognitive illusions

Unlike those demonstrating a physical or physiological basis, cognitive illusions are those that occur through misdirecting stored knowledge and assumptions. The illusion occurs perceptually but is under some degree of conscious control (cognitive illusions can be reversed at will).[3]

- Ambiguous illusions are those in which an image or object can seem to shift in appearance because visual data cannot confirm a single view. The switch is perceptual, and involves interpretation from the mind. Popular examples are the Necker cube and the Rubin vase (reversible figures), tessellations, and completion figures (Kanizsa Triangle).

- Paradox illusions include objects that would be impossible to construct as continuous objects, such as the Penrose triangle or impossible staircases seen, for example, in the work of M. C. Escher. The impossible triangle is an illusion dependent on a cognitive misunderstanding that adjacent edges must join.[3] Such illusions occur as a byproduct of perceptual learning.

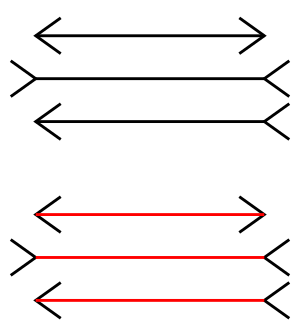

- Distorting illusions are those involving distortions of size, length, or curvature (perspective, depth, and distance) and are therefore more common in the natural world. Many are difficult to place as either physiological or cognitive. Well-known illusions include the Muller-Lyer illusion, Ebbinghaus illusion, and the Moon illusion.

- Fictional illusions are defined as the perception of objects that are genuinely not there to all but a single observer, such as those induced by schizophrenia or a hallucinogen.[3] These are more properly called hallucinations.

Well-known visual illusions

The following list includes many of those visual illusions that have been researched and are well known to the general public.

- Ames room illusion

- Autokinesis

- Barberpole illusion

- Benham's top

- Beta movement

- Bezold Effect

- Blivet (also known as the impossible trident illusion)

- Cafe wall illusion

- Chubb illusion

- Color Phi phenomenon

- Cornsweet illusion

- Ebbinghaus illusion

- Ehrenstein illusion

- Fraser spiral illusion

- Grid illusion (also known as Hermann grid illusion)

- Hering illusion

- Hollow-Face illusion

- Impossible cube

- Jastrow illusion

- Kanizsa triangle

- Lilac chaser

- Mach bands

- Moon illusion

- Muller-Lyer illusion

- Necker cube

- Orbison illusion

- Penrose triangle (also known as Impossible triangle illusion)

- Peripheral drift illusion

- Phi phenomenon

- Poggendorff illusion

- Ponzo illusion

- Rubin vase

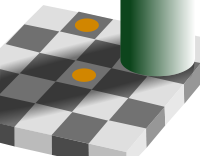

- Same color illusion

- White's illusion

- Wundt illusion

- Zollner illusion

Auditory illusions

Auditory illusions involve the sense of hearing. Hearing is achieved through sensitivity to the movement of molecules through a medium in the environment outside the organism. Individual species of organisms have sensitivities to frequencies that fall within a particular range. For example, humans are generally limited to frequencies between 20Hz to 20 kHz, which are commonly called audio or sonic frequencies. There are various illusions in which a listener may hear sounds that are not present in the stimulus, or "impossible" sounds. In short, auditory illusions highlight areas where the human ear and brain, as organic tools, differ from perfect audio receptors.

While not as well known or as well studied as visual illusions, a number of auditory illusions are quite common.

Octave Illusion - Discovered by Diana Deutsch in 1973, the octave illusion is an auditory illusion produced by playing an alternating sequence of two notes that are spaced an octave. The tones are played over headphones, with each ear receiving the tones simultaneously, except that when the right ear receives the high tone the left ear receives the low tone, and vice versa. Many people perceive a single tone that switches in pitch and from ear to ear, hearing, for example, "high tone - silence - high tone - silence" in the right ear while hearing "silence - low tone - silence - low tone" in the left ear. Surprisingly, right-handed people tend to hear the high tone in the right hear, while left-handers seem to show no tendencies.[4]

Glissando Illusion - Produced and demonstrated by Diana Deutsch in 1995, the glissando illusion is produced by an oboe tone played together with a sine wave that glides up and down in pitch. These two sounds are repeatedly switched between left and right, such that whenever the oboe tone is to the left, a portion of the glissando is to the right, and vice versa. When played over stereo loudspeakers, the oboe tone is heard correctly as jumping back and forth from ear to ear, whereas the segments of the glissando appear joined together. People localize the glissando in a variety of ways. Right-handers most often hear it as traveling from left to right as its pitch glides from low to high, while left-handers tend to obtain different illusions.[5]

Tritone Paradox - First published by Deutsch in 1986, this paradox is constructed by two computer-produced tones that are related by a half-octave (a tritone). When the two tones are played consecutively, some listeners hear the tones as ascending, while others hear the same tones as descending. This experience can be particularly astonishing to a group of musicians who are all quite certain of their judgments, and yet disagree completely as to whether such a pair of tones is moving up or down in pitch.[6]

McGurk Effect - This illusion is a perceptual phenomenon that shows the relation between hearing and seeing in speech perception, suggesting that speech perception relies on more than one modality. It was first described by McGurk and McDonald in 1976.[7] This effect may be experienced when a video of production of one phoneme is dubbed with a sound-recording of a different phoneme, the combination of which causes listeners to often perceive a third, intermediate phoneme. For example, a visual /ga/ combined with a heard /ba/ is often heard as /da/. The effect is robust, persisting even with knowledge of the illusion, unlike certain optical illusions that can break down once one 'sees through' them.

Shepard Tone - Created by psychologist Roger Shepard at Bell Labs, this illusion consists of a set of tones that seem to perpetually rise or fall. The illusion is created by super-positioning pure tones (sine waves) an octave apart. The brain's inability to identity the fundamental tone causes it to "slip" periodically, thereby creating the illusion, much like an eye looking at a barber pole pattern.

Gustatory, olfactory, and tactile Illusions

Knowledge of illusions in the physical senses of taste, smell, and touch is limited. There exist very few examples of illusions, perhaps due to the slower temporal resolution compared to that of vision and hearing. The following are examples of those that have been studied.

Phantom Limb - This tactile illusion is the sensation that an amputated body part, most commonly a limb, is still attached to the body. Most sensations are that of pain, but may include itching, warmth, cold, squeezing, and burning, although the limb may also feel as if it is shorter or in a distorted and painful position. Initially reasoned to be the product of inflamed nerve endings, phantom limb sensations have been found to be due to the reorganization of the somatosensory cortex. Stroking different parts of the face leads to perceptions of being touched on different parts of the missing limb.[8]

Thermal Grill - The thermal grill refers to a tactile illusion that was first demonstrated by T. Thunberg in 1896.[9] This illusion consists of an interlaced grill of bars, some of which are warm (say 40°C) and others cold (say 20°C) bars. Physical contact with this mixture of relatively mild temperatures elicits sensations of painful heat.

Haptic Illusions - Haptic illusions are created by mixing force cues with geometric cues to make people feel shapes that differ from the actual shape of the object.

Illusions in art

Art is illusionistic by nature. Even from the earliest forms of art, cave paintings that relied on outlines to suggest forms, illusion has been the bedrock of artworks. Modern science has found that such outline drawings can actually be recognized by the brain faster than a photograph of the object.[10]

Seemingly obvious principles of art, which are based on actually visual illusions, were not developed until the Italian Gothic time period (c. 1200-1400), when the use of lighting and shading to suggest form began taking hold. The Renaissance saw numerous discoveries of artistic principles that artists utilized to suggest reality. A mathematical approach to perspective was an especially crucial one; beforehand, artists inconsistently raised and enlarged objects and figures to suggest depth, which resulted in an unrealistic and flat image.

Color and contrast were also used to suggest depth; distant objects were rendered with lower contrast replicate the grayish cast caused by the scattering of light through distance in the atmosphere. Softer edges to suggest curvature, such as on bodies, were also popularly employed by artists who followed the Venetian school of the Italian Renaissance.

One particularly notable technique to achieve realism is the trompe-l'œil technique. This involves extremely realistic paintings which create the illusion that the objects depicted really exist as three-dimensional entities, sometimes within the dimension of the viewers themselves. This technique was frequently used during the Mannerist and Baroque artistic periods, though use of this technique dates back much further. It was often used to optically open up the domes or ceilings of a basilica to "reveal" the sky, upon which Jesus', Mary's, or various saint's ascensions were painted (sotto in su, meaning "seen from below" in Italian).

Mediums have expanded to include walls and even furniture, such as a deck of cards painted on a table, for example. A particularly impressive example can be seen at Chatsworth House in Derbyshire, where one of the internal doors appears to have a violin and bow suspended from it, in a trompe l'œil painted around 1723 by Jan van der Vaart.[11].

While there are countless artists who deliberately employed visual illusions to evoke a sense of reality in their artworks, there are many others who employed illusions for the sake of exhibiting the illusionary nature of art and perception, including Dutch graphic artist M. C. Escher, Bridget Riley, Salvador Dali, Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Marcel Duchamp, Oscar Reutersvard, and Charles Allan Gilbert.

Performance magic

Performance magic has also long been an art form, relying on baffling and amazing illusions to entertain audiences by giving the impression that something impossible has been achieved. Though the effect is that the performer seems to have supernatural abilities, the illusion of magic is created entirely by natural means. Illusions and acts may be characterized as production, vanish, transformation, restoration, teleportation, levitation, penetration, or sleight of hand illusions.

Mimes are also known for a repertoire of illusions that are created by physical means. The mime artist creates an illusion of acting upon, or being acted on by, an unseen object. These illusions exploit the audience's assumptions about the physical world. Well known examples include "walls," "climbing stairs," "leaning," "descending ladders," "pulling and pushing," and so forth.

Notes

- ↑ R. L. Solso, Cognitive Psychology (Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon, 2001, ISBN 0205309372)

- ↑ Diane M. Szaflarski, "How We See: The First Steps of Human Vision." Access Excellence Classic Collection. Retrieved August 9, 2007.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 "Illusions and Brain Teasers." World Mysteries. Retrieved August 9, 2007.

- ↑ Octave Illusion UCSD Department of Psychology. Retrieved August 16, 2007.

- ↑ Glissando Illusion UCSD Department of Psychology. Retrieved August 9, 2007.

- ↑ Tritone Paradox UCSD Department of Psychology. Retrieved August 9, 2007.

- ↑ Harry McGurk and John MacDonald, "Hearing lips and seeing voices," Nature 264(5588) (1976): 746–748.

- ↑ V. S. Ramachandran, D. C. Rogers-Ramachandran, and M. Stewart, "Perceptual Correlates of Massive Cortical Reorganization," Science 258(5085) (1992): 1159-1160.

- ↑ T. Thunberg, "Förnimmelserne vid till samma ställe lokaliserad, samtidigt pägäende köld-och värmeretning," Uppsala Läkfören Förh (1896): 489–495.

- ↑ "Illusion in Art." IllusionWorks L.L.C. (1997). Retrieved August 9, 2007.

- ↑ "Chatsworth Photo Library." Chatsworth. Retrieved August 9, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Deutsch, Diana. Research and Musical Illusions Demonstrations. UCSD Department of Psychology. Retrieved April 30th, 2007.

- Eagleman, D.M. "Visual Illusions and Neurobiology." Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2(12) (2001): 920-926. Retrieved August 21, 2007.

- Fineman, Mark. The Nature of Visual Illusion. New York, NY: Dover Publications, 1996. ISBN 0486291057

- Flanagan, J.R., Lederman, S.J. "Neurobiology: Feeling bumps and holes, News and Views" Nature 412(6845) (2001): 389–391. Retrieved August 24, 2007.

- Gregory, Richard L. Eye and Brain. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997. ISBN 0691048371

- Gregory, Richard L. "Knowledge in perception and illusion." Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond (1997). Retrieved August 21, 2007.

- Gregory, Richard L. Illusion: The Phenomenal Brain. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0192802859

- V. Hayward, O.R. Astley, M. Cruz-Hernandez, D. Grant, and G. Robles-De-La-Torre. "Haptic interfaces and devices" Sensor Review 24(1) (2004): 16–29. Retrieved August 24, 2007.

- Hoffman, Donald D. Visual Intelligence: How We Create What We See. New York, NY: W. W. Norton,2000. ISBN 0393319679

- Luckiesh, Matthew. Visual Illusions: Their Causes, Characteristics and Applications. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 1967. ISBN 048621530X

- McGurk, Harry, and John MacDonald. "Hearing lips and seeing voices." Nature 264(5588) (1976): 746–748.

- Ninio, Jacques. The Science of Illusions. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2001. ISBN 0801437709

- Purves D, Lotto B. Why We See What We Do: An Empirical Theory of Vision. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates, 2002.

- Purves D, Lotto B. and Nundy S. "Why We See What We Do." American Scientist 90(3) (2002): 236-242.

- Purves D, Williams MS, Nundy S., and Lotto RB. "Perceiving the intensity of light." Psychological Rev. 111 (2004): 142-158.

- Ramachandran, V. S., D. C. Rogers-Ramachandran & M. Stewart. "Perceptual Correlates of Massive Cortical Reorganization." Science 258(5085) (1992): 1159-1160.

- Renier, L., C. Laloyaux, O. Collignon, D. Tranduy, A. Vanlierde, R. Bruyer, A.G. De Volder. "The Ponzo illusion using auditory substitution of vision in sighted and early blind subjects." Perception 34 (2005): 857–867.

- Renier, L., R. Bruyer, and A.G. De Volder. "Vertical-horizontal illusion present for sighted but not early blind humans using auditory substitution of vision." Perception & Psychophysics 68 (2006): 535–542.

- Robinson, J. O. The Psychology of Visual Illusion. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 1998. ISBN 978-0486404493

- Robles-De-La-Torre G. & Hayward V. "Force Can Overcome Object Geometry In the perception of Shape Through Active Touch" Nature 412(6845) (2001): 445–448. Retrieved August 24, 2007.

- Robles-De-La-Torre G. M-2006.pdf "The Importance of the Sense of Touch in Virtual and Real Environments" IEEE Multimedia 13(3) (2006):24–30. Retrieved August 24, 2007.

- Seckel, Al. Optical Illusions: The Science of Visual Perception. Tonawanda, NY: Firefly Books, 2006. ISBN 978-1554071722

- Solso. R. L. Cognitive Psychology. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon, 2001. ISBN 0205309372

- Yang, Z and D. Purves. "A statistical explanation of visual space." Nature Neuroscience 6 (2003): 632-640.

- World-Mysteries.com. "Illusions and Brain Teasers". World Mysteries. Retrieved May 12th, 2007.

- IllusionWorks. Illusion in Art. IllusionWorks L.L.C.. Retrieved April 20th, 2007.

External links

All links retrieved November 28, 2024.

- Optical Illusions Pictures BrainDen.com

- Explore, learn and have Fun with Optical Illusions Archimedes' Laboratory.

- Visual Phenomena & Optical Illusions by Michael Bach.

- Fermüller, Cornelia. Theory of Optical Illusions

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.