The Inca Empire (called Tawantinsuyu in modern spelling, Aymara and Quechua, or Tahuantinsuyu in old spelling Quechua), was an empire located in South America from 1438 C.E. to 1533 C.E. Over that period, the Inca used conquest and peaceful assimilation to incorporate in their empire a large portion of western South America, centered on the Andean mountain ranges. The Inca empire proved short-lived: by 1533 C.E., Atahualpa, the last Sapa Inca, was killed on the orders of the Conquistador Francisco Pizarro (1476–1541), marking the beginning of Spanish rule.

The official language of Tahuantinsuyu was Quechua, although over seven hundred local languages were spoken. The Inca leadership encouraged the worship of their gods, the foremost of which was Inti, the sun god.

The empire was divided into four provinces (suyu), whose corners met at the empire's capital, Cusco (Qosqo). Tawantin means "a group of four," so the Quechua name for the empire, Tawantinsuyu, means "the four provinces."

The English term Inca Empire is derived from the word Inca, which was the title of the emperor. Today the word Inca still refers to the emperor, but can also refer to the people or the civilization, and is used as an adjective when referring to the beliefs of the people or the artifacts they left behind. The Inca Civilization was wealthy and well-organized, with generally humane treatment of its people, including the vanquished. The empire was really a federal system. It took the Spanish just eight years to all but destroy the richest culture in the Americas, replacing it with a much less just system. Indeed, it has been argued that the Inca's government allowed neither misery nor unemployment, as production, consumption, and demographic distribution reached almost mathematical equilibrium. The main legacy of the civilization lies in its power to inspire, including that of later resistance groups in the area against Spanish rule.

Origin stories

The Inca had two origin beliefs. In one, Tici Viracocha of Colina de las Ventanas in Pacaritambo sent forth his four sons and four daughters to establish a village. Along the way, Sinchi Roca was born to Manco Capac and Mama Ocllo, and Sinchi Roca is the person who finally led them to the valley of Cuzco where they founded their new village. There, Manco became their leader and became known as Manco Capac.

In the other origin myth, the sun god Inti ordered Manco Capac and Mama Ocllo to emerge from the depths of Lake Titicaca and found the city of Cuzco. They traveled by means of underground caves until reaching Cuzco where they established Sapa Inca, Hurin Cuzco, or the first dynasty of the Kingdom of Cuzco.

We know of these myths mostly by means of oral tradition. It is usually claimed that the Incas did not have writing although this has been challenged. It would be unusual for as advanced a civilization not to have developed some form of writing. Many now suggest that there was a writing system but that it has not yet been discovered.

There probably did exist a Manco Capac who became the leader of his tribe. The archeological evidence seems to indicate that the Inca were a relatively unimportant tribe until the time of Sinchi Roca, also called Cinchi Roca, who is the first figure in Inca mythology whose existence can be supported historically.

Emergence and Expansion

The Inca people began as a tribe in the Cuzco area around the twelfth century C.E. Under the leadership of Manco Capac, they formed the small city-state of Qosqo, or Cuzco in Spanish. In 1438 C.E., under the command of Sapa Inca (paramount leader) Pachacuti (or Pachacutec) (1438–1471), they began their conquest of the Andean regions of South America and adjacent lands. At its height, Tahuantinsuyu included what are now Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, and also extended into portions of what are now Chile, Argentina, and Colombia.

Pachacutin (which means transformer of the world), described by some as the most enlightened ruler in pre-Columbus America, reorganized Cuzco into the Tahuantinsuyu. The Tahuantinsuyu was a federalist system which consisted of a central government with the Inca at its head and four provincial governments with powerful leaders: Chinchasuyu (NW), Antisuyu (NE), Contisuyu (SW), and Collasuyu (SE). The four corners of these provinces met at the center, Cuzco. The land Pachacuti conquered was about the size of the thirteen colonies of the United States in 1776 C.E., and consisted of nearly the entire Andes mountain range. Tahuantinsuyu as of 1463 C.E. is shown in red on the map. Pachacuti is also thought to have built Machu Picchu, either as a family home or as a Camp David-like retreat.

Pachacuti would send spies to regions he wanted in his empire who would report back on their political organization, military might, and wealth. He would then send messages to the leaders of these lands extolling the benefits of joining his empire, offering them presents of luxury goods such as high quality textiles, and promising that they would be materially richer as subject rulers of the Inca. Most accepted the rule of the Inca as a fait accompli and acquiesced peacefully. The ruler's children would then be brought to Cuzco to be taught about Inca administration systems, then return to rule their native lands. This allowed the Inca to indoctrinate the former ruler's children into the Inca nobility, and, with luck, marry their daughters into families at various corners of the empire.

Pachacuti's son, Túpac Inca, conquered even more land, most importantly the Kingdom of Chimor, the Inca's only serious rival for the coast of Peru. Túpac Inca's empire stretched north into modern-day Ecuador and Colombia.

Huayna Cápac added some land area though less than his father and grandfather.

Tahuantinsuyu was a patchwork of languages, cultures, and peoples. The components of the empire were not all uniformly loyal, nor were the local cultures all fully integrated. For instance, the Chimú used money in their commerce, while the Inca empire as a whole had an economy based on exchange and taxation of luxury goods and labor (it is said that Inca tax collectors would take the head lice of the lame and old as a symbolic tribute). The portions of the Chachapoya that had been conquered were almost openly hostile to the Inca, and the Inca nobles rejected an offer of refuge in their kingdom after their troubles with the Spanish.

Spanish conquest and Vilcabamba

In 1532, when Spanish explorers led by Francisco Pizarro arrived on the coast of Peru, the empire stretched as far north as present-day Colombia and as far south as Chile and Argentina. However, a war of succession and unrest among newly conquered territories had already considerably weakened the empire. Pizarro did not have a formidable force; with fewer than 200 men and only 27 horses, he often needed to talk his way out of potential confrontations that could have easily wiped out his party. However, many people joined Pizarro's army on the way, increasing the force to several thousand. The Inca Emperor Atahualpa and his army fought fiercely against the Spanish conquistadors during the Battle of Cajamarca, but could not simultaneously face the technology of the Spanish (particularly firearms and cannons) and rebellion among subject tribes. Cuzco was definitively lost in 1536. On August 29, 1553, Atahualpa was executed by the Spanish. Told at the last moment that if he accepted Christian baptism, he would be dealt with mercifully, he did so. Subsequently, he was garroted instead of burned (Hyams and Ordish: 254). He was charged with treason against Pizarro. Hyams and Ordish (1963) comment that, “Spanish Catholicism was by Peruvian standards, atrocious” (260). The Inca leadership retreated to the mountain regions of Vilcabamba, where it remained for over another thirty years. In 1572, the last of the Inca rulers, Túpac Amaru, was beheaded and Tahuantinsuyu officially came to an end.

The Peruvians had experience of fighting but their wars were humane and the vanquished were treated with respect. The Spanish rules of war were different, since they did not hesitate to use treachery, torture, or cruelty to get what they wanted, ironically in the name of a God of Love. Hyams and Ordish wrote that the Peruvians:

- now found themselves opposed to a new kind of human being who waged war à outrance, inspired by a terrifying religion which enabled them to use treachery, hypocrisy, cruelty, torture, and massacre in the name of a God of Love; who were indifferent to the suffering they inflicted and superhumanly stoical in bearing suffering which their own conduct entailed for themselves…(260)

Some Spanish report that they were mistaken as gods by the Incas, who were expecting the return of their creator god, Viracocha. He is said to have been a tall, white man with a white robe and something resembling a breviary, which the Catholic priests carried. Hemming (2003) comments that, 'There is little evidence to support this idea. Atahualpa and his military commanders clearly regarded the Spaniards as ordinary mortals and had little hesitation in fighting them” (98). However, several contemporary Spanish writers do mention this identification, which of course had a parallel in Cortez's identification with Quetzalcoatl.

After the Spanish conquest

After the fall of Tahuantinsuyu, the new Spanish rulers brutally repressed the people and their traditions. Many aspects of Inca culture were systematically destroyed, including their sophisticated farming system. The Spanish used the Inca Mita (mandatory public service) system to literally work the people to death. One member of each family was forced to work in the gold and silver mines, the foremost of which was the titanic silver mine at Potosí. When one family member died, which would usually happen within a year or two, the family would be required to send a replacement. As elsewhere in the Americas, many died from the diseases brought by the Spanish.

The major languages of the empire, Quechua language and Aymara language, were employed by the Catholic Church to evangelize in the Andean region. In some cases, these languages were taught to peoples who had originally spoken other indigenous languages. Today, Quechua and Aymara remain the most widespread Amerindian languages.

The legend of the Inca has served as inspiration for resistance movements in the region. These include the 1780 rebellion led by Tupac Amaru II against the Spanish, as well as the contemporary guerrilla movements Tupac Amaru Revolutionary Movement (MRTA) and Sendero Luminoso in Peru and Tupamaros in Uruguay.

Tawantinsuyu has a modern rainbow flag which is displayed throughout Peru.

Society

Political organization of the empire

The most powerful figure in the empire was the Sapa Inca (emperor), or simply Inca. When a new ruler was chosen, his subjects would build his family a new royal dwelling. The former royal dwelling would remain the dwelling of the former Inca's family. Only descendants of the original Inca tribe ever ascended to the level of Inca. Most young members of the Inca's family attended Yachayhuasis (houses of knowledge) to obtain their education.

The Tahuantinsuyu was a federation which consisted of a central government with the Inca at its head and four provinces: Chinchaysuyu (NW), Antisuyu (NE), Qontisuyu (SW), and Qollasuyu (SE). The four corners of these provinces met at the center, Cuzco. Each province had a governor who oversaw local officials, who in turn supervised agriculturally productive river valleys, cities, and mines. There were separate chains of command for both the military and religious institutions, which created a system of partial checks and balances on power. The local officials were responsible for settling disputes and keeping track of each family's contribution to the Mita (mandatory public service). The Inca's system of leaving conquered rulers in post as proxy rulers, and of treating their subject people well, was very different from what was practiced elsewhere in South America.

The four provincial governors were called apos. The next rank down, the t'oqrikoq (local leaders), numbered about 90 in total and typically managed a city and its hinterlands. Below them were four levels of administration:

| Level name | Mita payers |

| Hunu kuraqa | 10,000 |

| Waranqa kuraqa | 1,000 |

| Pachaka kuraqa | 100 |

| Chunka kamayuq | 10 |

Every five waranqa curaca, pachaka curaca, and chunka kamayuq, had a intermediary to the next level called, respectively, picqa waranqa curaca, picqa pacaka curaca, and picqa conka kamayoq. This means that the middle managers managed either two or five people, while the conka kamayoq (at the worker manager level) and the apos and t'oqrikoq (in upper management) each had about 20 people reporting to them.

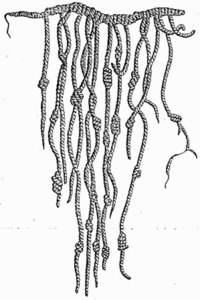

The descendants of the original Inca tribe were not numerous enough to administer their empire without help. To cope with the need for leadership at all levels the Inca established a civil service system. Boys at the age of 13 and girls at the age of first menstruation had their intelligence tested by the local Inca officials. If they failed, their ayllu (extended family group) would teach them one of many trades, such as farming, gold working, weaving, or military skills. If they passed the test, they were sent to Cuzco to attend school to become administrators. There they learned to read the quipu (knotted cord records) and were taught Inca iconography, leadership skills, religion, and, most importantly, mathematics. The graduates of this school constituted the nobility and were expected to marry within that nobility.

While some workers were held in great esteem, such as royal goldsmiths and weavers, they could never themselves enter the ruling classes. The best they could hope for was that their children might pass the exam as adolescents to enter the civil service. Although workers were considered the lowest social class, they were entitled to a modicum of what today we call due process, and all classes were equally subject to the rule of law. For example, if a worker was accused of stealing and the charges were proven false, the local official could be punished for not doing his job properly. Work was obligatory and there was a strong preference for collective work. One of the commandments was: "Do not be lazy"—beggars did not exist.

Arts

The Inca were a conquering society, and their expansionist assimilation of other cultures is evident in their artistic style. The artistic style of the Inca utilized the vocabulary of many regions and cultures, but incorporated these themes into a standardized imperial style that could easily be replicated and spread throughout the empire. The simple abstract geometric forms and highly stylized animal representation in ceramics, wood carvings, textiles, and metalwork were all part of the Inca culture. The motifs were not as revivalist as previous empires. No motifs of other societies were directly used with the exception of Huari and Tiwanaku arts.

Architecture

Architecture was by far the most important of the Inca arts, with pottery and textiles reflecting motifs that were at their height in architecture. The stone temples constructed by the Inca used a mortarless construction process first used on a large scale by the Tiwanaku. The Inca imported the stoneworkers of the Tiwanaku region to Cuzco when they conquered the lands south of Lake Titicaca. The rocks used in construction were sculpted to fit together exactly by repeatedly lowering a rock onto another and carving away any sections on the lower rock where the dust was compressed. The tight fit and the concavity on the lower rocks made them extraordinarily stable in the frequent earthquakes that strike the area. The Inca used straight walls except on important religious sites and constructed whole towns at once.

The Inca also sculpted the natural surroundings themselves. One could easily think that a rock along an Inca road or trail is completely natural, except if one sees it at the right time of year when the sun casts a stunning shadow, betraying its synthetic form. The Inca rope bridges were also used to transport messages and materials by Chasqui, or running messengers, who operated a type of postal service, essential in a mountain society. They lived in pairs and while one slept, the other waited for any message that needed to be sent. They ran 200 meters per minute and never a distance greater than 2 kilometers, relaying the message to the next team.

The Inca also adopted the terraced agriculture that the previous Huari civilization had popularized. But they did not use the terraces solely for food production. At the Inca tambo, or inn, at Ollantaytambo the terraces were planted with flowers, extraordinary in this parched land.

The terraces of Moray were left unirrigated in a desert area and seem to have been solely decorative. The Inca provincial thrones were often carved into natural outcroppings, and there were over 360 natural springs in the areas surrounding Cuzco, such as the one at Tambo Machay. At Tambo Machay the natural rock was sculpted and stonework was added, creating alcoves and directing the water into fountains. These pseudo-natural carvings functioned to show both the Inca's respect for nature and their command over it.

Clothing

Inca officials wore stylized tunics that indicated their status. The tunic displayed here is the highest status tunic known to exist today. It contains an amalgamation of motifs used in the tunics of particular officeholders. For instance, the black and white checkerboard pattern topped with a red triangle is believed to have been worn by soldiers of the Inca army. Some of the motifs make reference to earlier cultures, such as the stepped diamonds of the Huari and the three-step stairstep motif of the Moche. In this royal tunic, no two squares are exactly the same.

Cloth was divided into three classes. Awaska was used for household use and had a threadcount of about 120 threads per inch. Finer cloth was called qunpi and was divided into two classes. The first, woven by male qunpikamayuq (keepers of fine cloth), was collected as tribute from throughout the country and was used for trade, to adorn rulers, and to be given as gifts to political allies and subjects to cement loyalty. The other class of qunpi ranked highest. It was woven by aqlla (female virgins of the sun god temple) and used solely for royal and religious use. These had threadcounts of 600 or more per inch, unexcelled anywhere in the world until the Industrial Revolution in the nineteenth century.

Aside from the tunic, a person of importance wore a llawt'u, a series of cords wrapped around the head. To establish his importance, the Inca Atahualpa commissioned a llawt'u woven from vampire bat hair. The leader of each ayllu, or extended family, had its own headdress.

In conquered regions, traditional clothing continued to be worn, but the finest weavers, such as those of Chan Chan, were transferred to Cusco and kept there to weave qunpi. (The Chimú had previously transferred these same weavers to Chan Chan from Sican.)

The wearing of jewelry was not uniform throughout the empire. Chimú artisans, for example, continued to wear earrings after their integration into the empire, but in many other regions, only local leaders wore them.

Ceramics and metalwork

Ceramics were for the most part utilitarian in nature, but also incorporated the imperialist style that was prevalent in the Inca textiles and metalwork. In addition, the Inca played drums and woodwind instruments including flutes, pan-pipes, and trumpets made of shell and ceramics.

The Inca made beautiful objects of gold. But precious metals were in much shorter supply than in earlier Peruvian cultures. The Inca metalworking style draws much of its inspiration from Chimú art and in fact the best metal workers of Chan Chan were transferred to Cusco when the Kingdom of Chimor was incorporated into the empire. Unlike the Chimú, the Inca do not seem to have regarded metals to be as precious as fine cloth. When the Spanish first encountered the Inca they were offered gifts of qompi cloth.

Education

The Inca did not possess a written or recorded language as far as is known, but scholars point out that because we do not fully understand the quipu (knotted cords) we cannot rule out that they had recorded language. Like the Aztecs, they also depended largely on oral transmission as a means of maintaining the preservation of their culture. Inca education was divided into two distinct categories: vocational education for common Inca and highly formalized training for the nobility. Haravicus, or poets, enjoyed prestige.

Childhood

Inca childhood was harsh by modern standards. When a baby was born, the Inca would wash the child in cold water and wrap it in a blanket. Soon after, the baby was put in a pit dug in the ground like a playpen. By about age one, they expected the baby to crawl and walk independently. At age two, the child was ceremonially named and was considered to have left infancy. From then on, boys and girls were expected to help around the house. Misbehaving during this time could result in very severe punishment. At age fourteen, boys received a loincloth in a ceremony to mark their manhood. Boys from noble families were subjected to many different tests of endurance and knowledge. After the test, they received earplugs and a weapon, whose color represented rank in society.

Religion

The Tahuantinsuyu, or Incan religion was pantheist (sun god, earth goddess, corn god, etc.). Subjects of the empire were allowed to worship their ancestral gods as long as they accepted the supremacy of Inti, the sun god, which was the most important god worshiped by the Inca leadership. Consequently, ayllus (extended families) and city-states integrated into the empire were able to continue to worship their ancestral gods, though with reduced status. Much of the contact between the upper and lower classes was religious in nature and consisted of intricate ceremonies that sometimes lasted from sunrise to sunset. The main festival was the annual sun-celebration, when thanksgiving for the crop was given and prayers for an even better harvest next year. Before the festival, the people fasted and abstained from sex. Mummies of distinguished dead were brought to observe the ceremonies. Solemn hymns were sung and ritual kisses blown towards the sun-god. The king, as son of the sun god, drank from a ceremonial goblet, then the elders also drank. A llama was also sacrificed by the Willaq Uma, or High Priest, who pulled out the lungs and other parts with which to predict the future. A sacred fire was lit by using the sun's heat. Sanqhu, a type of “holy bread” was also offered.

Following the conquest by Spain, the religion of the Incas was systematically destroyed:

- During the last third of the sixteenth century and the start of the seventeenth, the Church launched an aggressive campaign to eradicate any spiritual opposition. A synod in Quito in 1570 instructed curates to attack “any ministers of the devil who obstruct the spread of our Christian religion”… Any leaders of the native religion were rooted out and flogged, placed in stocks or imprisoned ...priests ... went about the task with apostolic fervor… (Hemming, 2003: 397–398).

Hemming comments that this campaign was not wholly successful, since to this day every village market “has a few weird objects with magical significance” for sale and Peruvian Catholicism is said to contain many pre-Christian beliefs and customs.

Medicine

The Inca made many discoveries in medicine. They performed successful skull surgery. Coca leaves were used to lessen hunger and pain. The Chasqui (messengers) ate coca leaves for extra energy to carry on their tasks as runners delivering messages throughout the empire. Recent research by Erasmus University and Medical Center workers Sewbalak and Van Der Wijk showed that, contrary to popular belief, the Inca people were not addicted to the coca substance. Another remedy was to cover boiled bark from a pepper tree and place it over a wound while still warm. The Inca also used guinea pigs for not only food but for a so-called well-working medicine.

Burial practices

The Inca believed in reincarnation. Those who obeyed the Incan moral code—ama suwa, ama llulla, ama quella (do not steal, do not lie, do not be lazy)—went to live in the sun's warmth. Others spent their eternal days in the cold earth.

The Inca also believed in mummifying prominent personages. The mummies would be provided with an assortment of objects which were to be taken into the pacarina. Upon reaching the pacarina, the mummies or mallqui would be able to converse with the area's other ancient ancestors, the huacas. The mallquis were also used in various rituals or celebrations. The deceased were generally buried in a sitting position. One such example was the 500-year-old mummy “Juanita the Ice Maiden,” a girl very well-preserved in ice that was discovered at 20,000 feet, near the summit of Mt. Ampato in southern Peru. Her burial included many items left as offerings to the Inca gods. Similarity with Egyptian funeral and after-death practices has led some to speculate that if the ancient Phoenicians did travel to the Americas, there may have been some cross-fertilization between the two cultures. The role of the Sapa Inca has been compared to that of the Pharoahs; both were political and religious figures.

Food and farming

It is estimated that the Inca cultivated around 70 crop species. The main crops were potatoes (about 200 varieties), sweet potatoes, maize, chili peppers, cotton, tomatoes, peanuts, an edible root called oca, and a grain known as quinoa. The many important crops developed by the Inca and preceding cultures makes South America one of the historic centers of crop diversity (along with the Middle East, India, Mesoamerica, Ethiopia, and the Far East). Many of these crops were widely distributed by the Spanish and are now important crops worldwide.

The Inca cultivated food crops on dry Pacific coastlines, high on the slopes of the Andes, and in the lowland Amazon rainforest. In mountainous Andean environments, they made extensive use of terraced fields which not only allowed them to put to use the mineral-rich mountain soil that other peoples left fallow, but also took advantage of micro-climates conducive to a variety of crops being cultivated throughout the year. Agricultural tools consisted mostly of simple digging sticks.

The Inca also raised llamas and alpacas for their wool and meat and to use them as pack animals, and captured wild vicuñas for their fine hair.

The Inca road system was key to farming success as it allowed distribution of foodstuffs over long distances. The Inca also constructed vast storehouses, which allowed them to live through El Niño (less abundant) years in style while neighboring civilizations suffered.

Inca leaders kept records of what each ayllu in the empire produced, but did not tax them on their production. They instead used the mita for the support of the empire.

The Inca diet consisted primarily of fish and vegetables, supplemented less frequently with the meat of guinea pigs and camelids. In addition, they hunted various animals for meat, skins, and feathers. Maize was used to make chicha, a fermented beverage.

Currency

Inca society was based on a barter system. Workers got labor credit, which was work paid for in goods or food. It was well used in their day. It was a very good system for their needs

Legacy

The Spanish saw little or no reason to preserve anything they encountered in Inca civilization. They plundered its wealth and left the civilization in ruin. The civilization's sophisticated road and communication system and governance were no mean accomplishments. Diverse tribes, many occupying isolated territories in the most obscure of mountain hideaways, were simply remarkable. They were greedy for the wealth, which existed in fabulous proportion, not the culture. Yet, through the survival of the language and of a few residual traces of the culture, the civilization was not wholly, although almost wholly, destroyed. The great and relatively humane civilization of the Incas' main legacy is inspirational, residing in the human ability to imagine that such a fabulously rich, well-ordered, and generally humane society once existed, high up in the Andean hills.

Writers comment it was for “God, gold, and glory” that the conquest of the New World took place. The Indians "were enslaved, tortured, and worked to death to provide the Europeans with gold. They were infected by the newcomers with tuberculosis, measles, and smallpox" (Hyams and Ordish, 262). Edward Hyams said it best with his use of an analogy. He compared the Inca civilization to that of a dance where all of the patterns are the same and it continues day to day without faltering or interruption. He says, "The great dance had been their reality; they awoke into the nightmare of chaos" (263). In the contemporary world, where Europeans and North Americans often depict themselves as the bringers of peace, order, humaneness, and good governance, it is germane to compare the governance of the Peruvians before and after the Spanish conquest.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Andrein, Kenneth. Andean Worlds. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 2001. ISBN 0826323588

- Hemming, John. Conquest of the Incas. Orlando, FL: Harvest/HBJ Book, 2003. ISBN 0156028263

- Hyams, Edward and George Ordish. The Last of the Incas. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster, 1963. ISBN 0880295953

- Stone-Miller, Rebecca. Art of the Andes, from Chavin to Inca. New York, NY: Thames & Hudson, 1995. ISBN 0500203636

External links

All links retrieved November 28, 2024.

- Inca Land by Hiram Bingham (published 1912–1922)

- Tupac Amaru, the Life, Times, and Execution of the Last Inca.

- Inca stone cutting techniques Theory on how the Inca walls fit so perfectly.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.