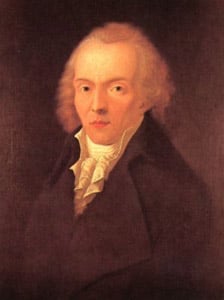

Jean Paul

Jean Paul (March 21, 1763 â November 14, 1825), born Johann Paul Friedrich Richter, was a German writer, best known for his humorous novels and stories. Jean Paul was influenced by his reading of satirists Jonathan Swift and Laurence Sterne, as well as the sensual rationalism of Helvetius and Baron d'Holbach. His works were immensely popular during the first two decades of the nineteenth century. They formed an important link between the eighteenth century classicism and the nineteenth century Romanticism that would follow. While known for his humorous novels, Paul liked to use the theme of the double, which would later become prevalent in the works of E.T.A. Hoffmann and Fyodor Dostoevsky. The double reflects the nature of human relationships, as expressed in the Biblical Cain and Abel story, in which two brothers must find a way to reconcile not only their differences but also their similarities, their common shared humanity.

Life and Work

Jean Paul was born at Wunsiedel, in the Fichtelgebirge Mountains (Bavaria). His father was a schoolmaster and organist at Wunsiedel, but in 1765 he became a pastor at Joditz near Hof, Germany, and in 1776 at Schwarzenbach, where he died in 1779. After attending the gymnasium at Hof, Richter went to the University of Leipzig in 1781. His original intention was to enter his father's profession, but theology did not interest him, and he soon devoted himself wholly to the study of literature. Unable to maintain himself at Leipzig he returned in 1784 to Hof, where he lived with his mother. From 1787 to 1789 he served as a tutor at TĂŒpen, a village near Hof, and from 1790 to 1794 he taught the children of several families in a school he had founded in Schwarzenbach.

Richter began his career as a man of letters with GrönlĂ€ndische Prozesse (âGreenlandic Processesâ) and Auswahl aus des Teufels Papieren (âSelection from the Devil's Papersâ), the former of which was issued in 1783â1784, the latter in 1789. These works were not received with much favor, and in later life Richter himself had little sympathy with their satirical tone. His next book, Die unsichtbare Loge (âThe Invisible Lodgeâ), a romance, published in 1793, had all the qualities which were soon to make him famous, and its power was immediately recognized by some of the best critics of the day.

Encouraged by the reception of Die unsichtbare Loge, he sent forth in rapid succession Hesperus (1795)âwhich became the greatest hit since Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's Die Leiden des jungen Werthers (âThe Sorrows of Young Wertherâ) and made Jean Paul famousâ,Biographische Belustigungen unter der Gehirnschale einer Riesin (âBiographical Amusements under the Brainpan of a She-giantâ) (1796), Leben des Quintus Fixlein (âLife of Quintus Fixleinâ) (1796), Blumen- Frucht- und DornenstĂŒcke, oder Ehestand, Tod und Hochzeit des Armenadvokaten SiebenkĂ€s (âFlower, Fruit, and Thorn Pieces, or, The Married Life, Death, and Wedding of Advocate of the Poor SiebenkĂ€sâ) (1796â1797), Der Jubelsenior (âThe Jubilee Seniorâ) (1798), and Das Kampaner Tal (âThe Campanian Valleyâ) (1797). This series of writings won for Richter an assured place in German literature, and during the rest of his life every work he produced was welcomed by a wide circle of admirers. This "second period" of his work was characterized by an attempt to reconcile his earlier comic realism with his own sentimental enthusiasm.

After his mother's death he went to Leipzig in 1797, and in the following year to Weimar, where he had much pleasant intercourse with Johann Gottfried Herder, by whom he was warmly appreciated. He did not become intimate with Goethe and Friedrich Schiller, to both of whom his literary methods were repugnant, but in Weimar, as elsewhere, his remarkable conversational powers and his genial manners made him a favorite in general society. In 1801 he married Caroline Meyer, whom he met in Berlin in 1800. They lived first at Meiningen, then at Coburg, Germany, and finally, in 1804, they settled at Bayreuth.

Here Richter spent a quiet, simple, and happy life, constantly occupied with his work as a writer. In 1808 he was fortunately delivered from anxiety about outward necessities by the prince-primate, Karl Theodor von Dalberg, who gave him a pension of a thousand forms. Before settling at Bayreuth, Richter had published his most ambitious novel, Titan (1800â1803), which was followed by Flegeljahre (âThe Awkward Ageâ) (1804â1805). He regarded these two works as his masterpieces. His later imaginative works were Dr. Katzenbergers Badereise (âDr. Katzenberger's Spa Voyageâ) (1809), Des Feldpredigers Schmelzle Reise nach FlĂ€tz (âArmy Chaplain Schmelzle's Voyage to FlĂ€tzâ) (1809), Leben Fibels (âLife of Fibelâ) (1812), and Der Komet, oder Nikolaus Markgraf (âThe Comet, or Nikolaus Markgrafâ) (1820â1822). In Vorschule der Aesthetik (âPreschool of Aestheticsâ) (1804), he expounded his ideas on art, he discussed the principles of education in Levana, oder Erziehungslehre (âLevana, or, Doctrine of Educationâ) (1807), and the opinions suggested by current events he set forth in Friedenspredigt (âPiece Sermonâ) (1808), DĂ€mmerungen fĂŒr Deutschland (âDawn for Germanyâ) (1809), Mars und Phöbus Thronwechsel im Jahre 1814 (âMars's and Phoebus's Throne Change in the Year 1814â) (1814), and Politische Fastenpredigen (âPolitical Fast Sermonsâ) (1817). In his last years he began Wahrheit aus Jean Pauls Lebens (âThe Truth from Jean Paul's Lifeâ), to which additions from his papers and other sources were made by C. Otto and E. FĂŒrster after his death. In 1821 Richter lost his only son, a youth of the highest promise; and he never quite recovered from this shock. He lost his sight in 1824. He died of dropsy at Bayreuth, on November 14, 1825.

Characteristics of His Work

Schiller said of Richter that he would have been worthy of admiration if he had made as good use of his riches as other men made of their poverty. And it is true that in the form of his writings he never did full justice to his great powers. In working out his conceptions he found it impossible to restrain the expression of any powerful feeling by which he might happen to be moved. He was equally unable to resist the temptation to bring in strange facts or notions which occurred to him. Hence every one of his works is irregular in structure, and his style lacks directness, precision, and grace. But his imagination was one of extraordinary fertility, and he had a surprising power of suggesting great thoughts by means of the simplest incidents and relations. The love of nature was one of Richter's deepest pleasures; his expressions of religious feelings are also marked by a truly poetic spirit, for to Richter visible things were but the symbols of the invisible, and in the unseen realities alone he found elements which seemed to him to give significance and dignity to human life. His humor, the most distinctive of his qualities, cannot be dissociated from the other characteristics of his writings. It mingled with all his thoughts, and to some extent determined the form in which he embodied even his most serious reflections. That it is sometimes extravagant and grotesque cannot be disputed, but it is never harsh or vulgar, and generally it springs naturally from the perception of the incongruity between ordinary facts and ideal laws. Richter's personality was deep and many-sided; with all his willfulness and eccentricity, he was a man of a pure and sensitive spirit with a passionate scorn for pretence and an ardent enthusiasm for truth and goodness.

Reception

During his life time, Jean Paul was a bestselling author. After his death, however, his popularity faded away. This might also have been caused by the negative verdicts of Goethe and Schiller on his works. Since the twentieth century, he is again counted among the greatest German writers, though he is considered difficult to read because of his exuberant style and satirical footnotes. Strongly influenced by the English comic tradition of Sterne and Smollett, he does not belong to the literary canon that is usually read in the Gymnasium.

Nineteenth Century Works on Jean Paul

Richter's SĂ€mtliche Werke (âComplete Worksâ) appeared in 1826â1828 in 60 volumes, to which were added five volumes of Literarischer Nachlass (âLiterary Bequestâ) in 1836â1838; a second edition was published in 1840â1842 (33 volumes); a third in 1860â1862 (24 volumes). The last complete edition is that edited by Rudolf von Gottschall (60 parts, 1879). Editions of selected works appeared in 16 volumes (1865), in KĂŒrschner's Deutsche Nationalliteratur (edited by P. Nerrlich, six volumes), among others. The chief collections of Richter's correspondence are:

- Jean Pauls Briefe an F. H. Jacobi (1828)

- Briefwechsel Jean Pauls mit seinem Freunde C. Otto (1829â1833)

- Briefwechsel zwischen H. Voss und Jean Paul (1833)

- Briefe an eine Jugendfriundin (1858)

- Nerrlich, P. Jean Pauls Briefwechsel mit seiner Frau und seinem Freunde Otto (1902).

- Dring, H. J. P. F. Richters Leben und Charakteristik (1830â1832)

- Spazier, Richard Otto. JPF Richter: ein biographischer Commentar zu dessen Werken (5 vols, 1833)

- FĂŒrster, E. DenkwĂŒrdigkeiten aus dem Leben von J. P. F. Richter (1863)

- Nerrlich, Paul. Jean Paul und seine Zeitgenossen (1876)

- Firmery, J. Ătude sur la vie et les Ćuvres de J. P. F. Richter (1886)

- Nerrlich, P. Jean Paul, sein Leben und seine Werke (1889)

- Schneider, Ferdinand Josef. Jean Pauls Altersdichtung (1901)

- Schneider, Ferdinand Josef. Jean Pauls Jugend und erstes Auftreten in der Literatur (1906)

Richter's more important works, namely Quintus Fixlein and Schmelzles Reise, have been translated into English by Carlyle; see also Carlyle's two essays on Richter.

Quotations

- Joy is inexhaustible, not the seriousness.

- Many young people get worked up about opinions that they will share in 20 years.

- Too much trust is a foolishness, too much distrust a tragedy.

List of Works

- Leben des vergnĂŒgten Schulmeisterlein Maria Wutz (1790)

- Die unsichtbare Loge (1793)

- Hesperus (book) (1795)

- Leben des Quintus Fixlein (1796)

- SiebenkÀs (1796)

- Der Jubelsenior (1797)

- Das Kampaner Tal (1797)

- Titan (1802)

- Flegeljahre (unfinished) (1804)

- Levana oder Erziehlehre (1807)

- Dr. Katzenbergers Badereise (1809)

- Auswahl aus des Teufels Papieren

- Bemerkungen ĂŒber uns nĂ€rrische Menschen

- Biographische Belustigungen

- Clavis Fichtiana

- Das heimliche Klaglied der jetzigen MĂ€nner

- Der Komet

- Der Maschinenmann

- Des Feldpredigers Schmelzle Reise nach FlÀtz

- Des Luftschiffers Giannozzo Seebuch

- Die wunderbare Gesellschaft in der Neujahrsnacht

- Freiheits-BĂŒchlein

- GrönlÀndische Prozesse

- Leben Fibels

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Boesch, Bruno, ed. German Literature: A Critical Survey. London: Methuen & Co. 1971. ISBN 0416149405

- Friederich, Werner F. An Outline-History of German Literature. New York: Barnes and Noble. 1948. ISBN 9780064600651

- Lange, Victor. The Classical Age of German Literature: 1740â1815. New York: Holmes and Meier Publishers. 1982. ISBN 0-8419-0853-2

This article incorporates text from the EncyclopĂŠdia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

External Links

All links retrieved December 23, 2024.

- Projekt Gutenberg-DE. Jean Paul.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.