| |

| Born: | January 24, 1776 Königsberg, East Prussia |

|---|---|

| Died: | June 25, 1822 Berlin, Brandenburg, Prussia |

| Occupation(s): | jurist, author, composer, music critic, artist |

| Nationality: | German |

| Writing period: | 1809-1822 |

| Literary genre: | fantasy |

| Literary movement: | Romanticism |

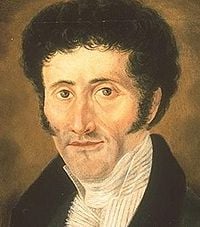

Ernst Theodor Wilhelm Hoffmann (January 24, 1776 ‚Äď June 25, 1822), better known by his pen name E. T. A. Hoffmann, was a Romantic author of fantasy and horror, a jurist, composer, music critic, draftsman and caricaturist. Hoffmann was one of the key authors of the later the Romantic movement and a transitional figure. His most familiar story, Nussknacker und Mausek√∂nig ("Nutcracker and Mouse King," 1816), was the basis for Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky's ballet The Nutcracker (1892); despite its appeal to children it contains dark psychological themes and social commentary on the issues of the day.

His work combined the strong emotion of Romanticism with the elements of fear and horror of gothic fiction, which was contemporaneous with his own time. Hoffmann's work illuminates the darker side of the human spirit, a preoccupation of the horror genre that followed.

Hoffmann's influence extended far beyond the more narrow area of the gothic novel. His stories had a profound effect on the development of the psychological novel which became prominent in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Nikolai Gogol, Fyodor Dostoevsky and Edgar Allen Poe are but a few of the writers who worked in the tradition of Hoffmann.

Life

Youth

Hoffmann's ancestors, both maternal and paternal, were jurists. His father, Christoph Ludwig Hoffmann (1736‚Äď1797) was a barrister in K√∂nigsberg, Prussia, and also a poet and amateur musician who played the viola da gamba. In 1767 he married his cousin Lovisa Albertina Doerffer (1748‚Äď1796). Ernst Theodor Wilhelm, born on January 24, 1776, was the youngest of three children, of whom the second died in infancy.

His parents separated in 1778, the father going to Insterburg (now Chernyakhovsk) with his elder son, Johann Ludwig Hoffmann (1768‚Äďafter 1822), while Ernst's mother stayed in K√∂nigsberg with her relatives: two aunts, Johanna Sophie Doerffer (1745-1803) and Charlotte Wilhelmine Doerffer (c. 1754-1779) and their brother, Otto Wilhelm Doerffer (1741‚Äď1811), who were all unmarried. This trio took it upon themselves to educate the youngster.

The household, dominated by the uncle (whom Ernst nicknamed O Weh or "Oh dear" in a play on his initials), was pietistic and uncongenial. Hoffmann was to regret his estrangement from his father. Nevertheless, he remembered his aunts with great affection, especially the younger, Charlotte, whom he nicknamed Tante F√ľ√üchen ("Aunt Littlefeet"). Although she died when he was only three years old, he treasured her memory (e.g., see Kater Murr) and embroidered stories about her to such an extent that later biographers sometimes assumed her to be imaginary, until proofs of her existence were found after World War II.[1]

Between 1781 and 1792 he attended the Lutheran school or Burgschule, where he made good progress in classics. He was taught drawing by one Saemann, and counterpoint by a Polish organist named Podbieski, who was to be the prototype of Abraham Liscot in Kater Murr. Ernst showed great talent for piano-playing, and busied himself with writing and drawing. The provincial setting was not, however, conducive to technical progress, and despite his many-sided talents he remained relatively ignorant, both of classical forms and of the new artistic ideas that were then developing in Germany. He had however read Friedrich Schiller, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Jonathan Swift, Laurence Sterne, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and Jean Paul, and wrote part of a novel called Der Geheimnisvolle.

Around 1787 he became friends with Theodor Gottlieb von Hippel (1775-1843), the son of a pastor and well-known writer friend of Immanuel Kant. In 1792, both attended some of Kant's lectures at the University. Their friendship, although often tested by a widening social gulf, was to be life-long.

In 1794, Hoffmann fell in love with Dora Hatt, a married woman to whom he had given music lessons. She was ten years older, and in 1795 gave birth to her sixth child. In February 1796, her family protested against his attentions, and, with his faltering consent, they asked another of his uncles to arrange employment for him in Glogau.[2]

The provinces

From 1796 he obtained employment as a clerk for his uncle, Johann Ludwig Doerffer, who lived in GŇāog√≥w (Glogau), Silesia with his daughter Minna. After passing further examinations he visited Dresden, where he was amazed by the paintings in the gallery, particularly those of Correggio and Raphael. In the summer of 1798 his uncle was promoted to a court in Berlin, and the three of them moved there in August ‚ÄĒ Hoffmann's first residence in a large city. It was there that Hoffmann first attempted to promote himself as a composer, writing an operetta called Die Maske and sending a copy to Queen Luise of Prussia. The official reply advised to him to write to the director of the Royal Theater, a man named Iffland. By the time the latter responded, Hoffmann had passed his third round of exams and had already left for Posen in South Prussia (now PoznaŇĄ) in the company of his old friend Hippel, after a brief stop in Dresden to show him the gallery.

From June 1800 to 1803 he worked in Prussian provinces in the area of Greater Poland and Mazovia. This was the first time he had lived without supervision by members of his family, and he started to become "what school principals, parsons, uncles, and aunts call dissolute." His first job, at Posen, was put in jeopardy after Carnival on Shrove Tuesday 1802, when caricatures of military officers were distributed at a ball. It was immediately deduced who had drawn them, and complaints were made to authorities in Berlin, who were reluctant to punish the promising young official. The problem was solved by "promoting" Hoffmann to PŇāock in New East Prussia, a muddy village which had recently gained importance after administrative offices were moved there from Thorn (now ToruŇĄ). He visited the place to arrange lodging, before returning to Posen where he married "Mischa" (Maria, or Marianna Thekla Michaelina Rorer, whose Polish surname was TrzyŇĄska). They moved to PŇāock in August 1802.

Hoffmann despaired over his exile, and drew caricatures of himself drowning in mud alongside ragged villagers. He did make use, however, of his isolation, by writing and composing. He started a diary on October 1, 1803. An essay on the theater was published in Kotzebue's periodical, Die Freim√ľthige, and he entered a competition in the same magazine to write a play. Hoffmann's play was called Der Preis ("The Prize"), and was itself about a competition to write a play. There were 14 entries, but none was judged worthy of the award: 100 Friedrichs d'or'. Nevertheless, his entry was singled out for praise.[3] This was one of the few high points in a sad period in his life, which saw the deaths of his uncle J. L. Hoffmann in Berlin, his Aunt Sophie, and Dora Hatt in K√∂nigsberg.

At the beginning of 1804 he obtained a post in Warsaw. On his way there, he passed through his hometown and met one of Dora Hatt's daughters. He was never to return to Königsberg.

Warsaw

Hoffmann assimilated well in Polish society; the years spent in Poland he recognized as the happiest in his life. In Warsaw he found the same atmosphere he had enjoyed in Berlin, renewing his friendship with Zacharias Werner, and meeting his future biographer, a neighbor and fellow jurist called Julius Eduard Itzig (who changed his name to Hitzig after his baptism). Itzig had been a member of the Berlin literary group called the Nordstern, and he gave Hoffmann the works of Novalis, Ludwig Tieck, Achim von Arnim, Clemens Brentano, Gotthilf Heinrich von Schubert, Carlo Gozzi, and Calderon. These relatively late introductions marked his work profoundly.

He moved in the circles of August Wilhelm Schlegel, Adelbert von Chamisso, Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué, and Rahl Levin.

Unfortunately, his fortunate position was not to last: on November 28, 1806, Napoleon's troops occupied Warsaw, and the Prussian bureaucrats lost their positions at a stroke. They divided the contents of the treasury between them and fled. In January 1807 his wife and two-year-old daughter Cäcilia returned to Posen, while he pondered whether to move to Vienna or go back to Berlin. A delay of six months was caused by severe illness. Eventually the French authorities demanded that all former officials swear allegiance or leave the country. As they refused to grant him a passport to Vienna, he was forced to return to Berlin. He visited his family in Posen before arriving in Berlin on June 18, 1807, hoping to further his career there as an artist and writer.

Berlin and Bamberg

The next fifteen months were some of the worst in Hoffmann's life. The city of Berlin was also occupied by Napoleon's troops, and it was in vain that he tried to pick up the pieces. Obtaining only meagre allowances, he had frequent recourse to his friends, constantly borrowing money and still going hungry for days at a time; he learned that his daughter had died. Nevertheless, he managed to compose his Six Canticles for a cappella choir: one of his best compositions, which he would later attribute to Kreisler in Lebensansichten des Katers Murr.

On 1 September 1808 he arrived with his wife in Bamberg, where he took up a position as theater manager. The director, Graf (Count) Soden, left almost immediately for W√ľrzburg, leaving a man named Heinrich Cuno in charge. Hoffmann was unable to improve standards of performance, and his efforts led to intrigues against him which resulted in him losing his job to Cuno. He began work as music critic for the Allgemeinen musikalischen Zeitung, a newspaper in Leipzig. It was in its pages that the "Kapellmeister Johannes Kreisler" character made his first appearance.

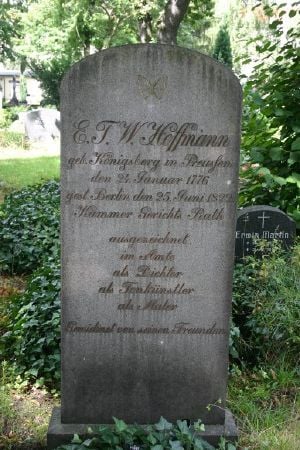

Hoffmann's breakthrough came in 1809, with the publication of Ritter Gluck, a story about a madman who believes he is the composer Christoph Willibald Gluck (1714-1787). He began to use the pen name E. T. A. Hoffmann, telling people that the "A" stood for Amadeus, in homage to the composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756‚Äď1791). However, he continued to use Wilhelm in official documents throughout his life, and the initials E. T. W. also appear on his gravestone.

The next year, he was employed at the Bamberg Theater as stagehand, decorator, and playwright, while also giving private music lessons. He fell so deeply in love with a young singing student, Julia Marc, that his feelings were obvious whenever they were together, and Julia's mother quickly found her a more suitable match. When Joseph Seconda offered Hoffmann a position as musical director for his opera company (then performing in Dresden), he accepted, leaving on April 21, 1813.

Dresden and Leipzig

Prussia had declared war against France on March 16, and their journey was fraught with difficulties. They arrived on the 25th, only to find that Seconda was in Leipzig; on the 26th, they sent a letter pleading for temporary funds. That same day Hoffmann was surprised to meet Hippel, whom he had not seen in nine years.

The situation deteriorated, and in early May Hoffmann tried in vain to find transport to Leipzig. On May 8, the bridges were destroyed, and his family was marooned in the city. During the day, Hoffmann would roam, watching the fighting with curiosity. Finally, on May 20, they left for Leipzig, only to be involved in an accident which killed one of the passengers in their coach and injured his wife.

They arrived on May 23, and Hoffmann started work with Seconda's orchestra, which he found to be of the highest quality. On June 4 an armistice began, which allowed the company to return to Dresden. But on August 22, after the end of the armistice, the family was forced to move from their pleasant house in the suburbs into town, and over the next few days the Battle of Dresden raged. The city was bombarded; many people were killed by bombs directly in front of him. After the main battle was over, he visited the gory battlefield. His account can be found in Vision auf dem Schlachtfeld bei Dresden. After a long period of continued disturbance the town surrendered on November 11, and on 9 December the company travelled to Leipzig.

On February 25 Hoffmann quarrelled with Seconda, and the next day he was given notice of 12 weeks. When asked to accompany them on their trip to Dresden in April, he refused, and they left without him. But in July his friend Hippel visited, and soon he found himself being guided back into his old career as a jurist.

Berlin

At the end of September 1814, in the wake of Napoleon's defeat, he returned to Berlin and succeeded in regaining a position at the Kammergericht, the chamber court. His opera Undine was performed by the Berlin Theater. Its successful run came to an end only after a fire on the night of the 25th performance. Magazines clamored for his contributions, and after a while his standards started to decline. Nevertheless, many masterpieces date from this time.

The period from 1819 saw Hoffmann embroiled in legal disputes, while battling ill health. Alcohol abuse and syphilis led eventually to weakening of the limbs in 1821, and paralysis from the beginning of 1822. His last works were dictated to his wife or to a secretary.

Metternich's anti-liberal crusades began to put Hoffmann in situations that tested his conscience. Thousands of people were accused of treason for having certain political opinions, and university professors were monitored during their lectures.

The King of Prussia appointed an Immediate Commission for the investigation of political dissidence; when he found its observance of the rule of law too frustrating, he established a Ministerial Commission to interfere with its processes. The latter was greatly influenced by Commissioner Kamptz. During the trial of Father Jahn, the leader of the Turmverein, Hoffmann found himself crossing the will of Kamptz, and became a political target. When Hoffmann caricatured Kamptz in a story (Meister Floh), Kamptz began legal proceedings. These petered out when Hoffmann's illness was seen to be life-threatening. The King asked for a reprimand only, but no action was ever taken. Eventually Meister Floh was published with the offending passages removed.

Hoffmann died in Berlin on June 25, 1822 at the age of 46, and is buried near the Hallesches Tor in the Jerusalem and New Churches Community Cemetery.

Assessment

Hoffmann wrote novels and short stories, and he composed music, including an opera, Undine (1814). Hoffmann's stories were written at a very sensitive time politically. Like Reinicke Fuchs or Aesop in his fables, Hoffmann used seemingly innocuous animal stories, such as his most familiar story, Nussknacker und Mausekönig ("Nutcracker and Mouse King", 1816), which inspired Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky's ballet The Nutcracker (1892), to comment on contemporary social and political issues.

The Nutcracker story is full of charming mimed phantasies with Marie (Clara in the ballet), Fritz and Pate Drosselmayr, the mean Mouse King and the ever popular Nutcracker. Many versions of have been published as children's books and Nutcracker performances have become a yearly feature in many cities around Christmas. Despite their obvious appeal to children, these stories introduce several philosophical themes and often express darker psychological themes. Hoffmann invariably explores the nature of Selfhood, Art and value-judgements. These are typical Romantic concerns and Hoffmann is one of the best-known representatives of German Romanticism, as well as a pioneer of the fantasy genre, but with a taste for the macabre combined with realism. His wide-ranging influence upon and creative significance within the later German romantic period is frequently underestimated, but his works were one of the major influences for the modern novel, including such prominent authors as Edgar Allan Poe (1809‚Äď1849), Nikolai Gogol (1809‚Äď1852), Charles Dickens (1812‚Äď1870), Charles Baudelaire (1821‚Äď1867), and Franz Kafka (1883‚Äď1924). Hoffmann's work illuminates the darker side of the human spirit found behind the seeming harmony of bourgeois life.

Jacques Offenbach's masterwork, the opera Les contes d'Hoffmann ("The Tales of Hoffmann," 1881), is based on the stories Der Sandmann ("The Sandman," 1816), Rath Krespel ("Councillor Krespel," 1818), and Das verlorene Spiegelbild ("The Lost Reflection") from Die Abenteuer der Silvester-Nacht ("The Adventures of New Year's Eve," 1814). Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky's ballet The Nutcracker (1892) is based on a story by Hoffmann.

Hoffmann also influenced nineteenth century musical taste directly through his music criticism. His reviews of Beethoven's Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67 (1808) and other important works set new literary standards for writing about music, and encouraged later writers to see music as "the most Romantic of all the arts." Hoffmann's reviews have been collected for modern readers by Friedrich Schnapp, ed., in E.T.A. Hoffmann: Schriften zur Musik; Nachlese (1963) and have been made available in an English translation by Andrew Crumey, ed., in E.T.A. Hoffmann's Writings on Music, Collected in a Single Volume (2004).

Hoffmann strove for artistic polymathy. He created far more in his works than mere political commentary achieved through satire. His masterpiece (it is generally agreed) is Lebensansichten des Katers Murr ("The Life and Opinions of Tomcat Murr," 1819‚Äď1821). This novel deals with such issues as the aesthetic status of 'true' artistry, and the modes of self-transcendence that accompany any genuine endeavor to create. Hoffmann's portrayal of the character Kreisler (a genius musician) is wittily counterpointed with the character of the tomcat Murr ‚ÄĒ a virtuoso illustration of artistic pretentiousness that many of Hoffmann's contemporaries found offensive and subversive of Romantic ideals.

Hoffmann's literature points to the failings of many so-called artists to differentiate between the superficial and the authentic aspects of such Romantic ideals. The self-conscious effort to impress must, according to Hoffmann, be divorced from the self-aware effort to create. This essential duality in Kater Murr is structurally conveyed through a discursive 'splicing together' of two biographical narratives. Such a framework warrants an extensive exploration of its philosophical implications.

Works

Literary

- Fantasiest√ľcke in Callots Manier (collection of previously published stories, 1814)

- Ritter Gluck, Kreisleriana, Don Juan, Nachricht von den neuesten Schicksalen des Hundes Berganza

- Der Magnetiseur, Der goldne Topf (revised in 1819), Die Abenteuer der Sylvesternacht

- Die Elixiere des Teufels (1815)

- Nachtst√ľcke (1817)

- Der Sandmann, Das Gel√ľbde, Ignaz Denner, Die Jesuiterkirche in G.

- Das Majorat, Das öde Haus, Das Sanctus, Das steinerne Herz

- Seltsame Leiden eines Theater-Direktors (1819)

- Klein Zaches, genannt Zinnober (1819)

- Die Serapionsbr√ľder (1819)

- Der Einsiedler Serapion, Rat Krespel, Die Fermate, Der Dichter und der Komponist

- Ein Fragment aus dem Leben dreier Freunde, Der Artushof, Die Bergwerke zu Falun, Nußknacker und Mausekönig (1816)

- Der Kampf der Sänger, Eine Spukgeschichte, Die Automate, Doge und Dogaresse

- Alte und neue Kirchenmusik, Meister Martin der K√ľfner und seine Gesellen, Das fremde Kind

- Nachricht aus dem Leben eines bekannten Mannes, Die Brautwahl, Der unheimliche Gast

- Das Fr√§ulein von Scuderi, Spielergl√ľck (1819), Der Baron von B.

- Signor Formica, Zacharias Werner, Erscheinungen

- Der Zusammenhang der Dinge, Vampirismus, Die ästhetische Teegesellschaft, Die Königsbraut

- Prinzessin Brambilla (1820)

- Lebensansichten des Katers Murr (1820)

- Die Irrungen (1820)

- Die Geheimnisse (1821)

- Die Doppeltgänger (1821)

- Meister Floh (1822)

- Des Vetters Eckfenster (1822)

Musical

Songs

- Messa d-moll (1805)

- Trois Canzonettes à 2 et à 3 voix (1807)

- 6 Canzoni per 4 voci alla capella (1808)

- Miserere b-moll (1809)

- In des Irtisch weiße Fluten (Kotzebue), Lied (1811)

- Recitativo ed Aria ‚ÄěPrendi l‚Äôacciar ti rendo‚Äú (1812)

- Tre Canzonette italiane (1812); 6 Duettini italiani (1812)

- Nachtgesang, T√ľrkische Musik, J√§gerlied, Katzburschenlied f√ľr M√§nnerchor (1819-21)

Works for stage

- Die Maske (Libretto: E. T. A. Hoffmann), Singspiel (1799)

- Die lustigen Musikanten (Libretto: Clemens Brentano), Singspiel (1804)

- B√ľhnenmusik zu Zacharias Werners Trauerspiel ‚ÄěDas Kreuz an der Ostsee‚Äú (1805)

- Liebe und Eifersucht (Calderón and August Wilhelm Schlegel) (1807)

- Arlequin, Ballettmusik (1808)

- Der Trank der Unsterblichkeit (Libretto: Julius von Soden), romantische Oper (1808)

- Wiedersehn! (Libretto: E. T. A. Hoffmann), Prolog (1809)

- Dirna (Libretto: Julius von Soden), Melodram (1809)

- B√ľhnenmusik zu Julius von Sodens Drama ‚ÄěJulius Sabinus‚Äú (1810)

- Saul, König von Israel (Libretto: Joseph von Seyfried), Melodram (1811)

- Aurora (Libretto: Franz von Holbein) heroische Oper (1812)

- Undine (Libretto: Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué), Zauberoper (1814)

- Der Liebhaber nach dem Tode (beginning only)

Instrumental

- Rondo f√ľr Klavier (1794/95)

- Ouvertura. Musica per la chiesa d-moll (1801)

- Klaviersonaten: A-Dur, f-moll, F-Dur, f-moll, cis-moll (1805-1808)

- Gro√üe Fantasie f√ľr Klavier (1806)

- Sinfonie Es-Dur (1806)

- Harfenquintett c-moll (1807)

- Grand Trio E-Dur (1809)

- Walzer zum Karolinentag (1812)

- Teutschlands Triumph in der Schlacht bei Leipzig, (by "Arnulph Vollweiler," 1814; lost)

- Serapions-Walzer (1818-1821)

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ Friedrich Schnapp. "Hoffmanns Verwandte aus der Familie Doerffer in K√∂nigsberger Kirchenb√ľchern der Jahre 1740-1811." Mitteilungen der E. T. A. Hoffmann-Gesellschaft. 23 (1977): 1-11.

- ‚ÜĎ R√ľdiger Safranski. E. T. A. Hoffmann: Das Leben eines skeptischen Phantasten. (Munich: Carl Hanser, 1984. ISBN 3446138226

Gerhard R. Kaiser. E. T. A. Hoffmann. (Stuttgart: J. B. Metzlersche, 1988. ISBN 3476102432) - ‚ÜĎ Die Freim√ľthige, 1804. Volume II, 6: xxi-xxiv.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

In English

- Crumey, Andrew, ed. E.T.A. Hoffmann's Writings on Music, Collected in a Single Volume. 2004.

- Röder, Birgit. A study of the major novellas of E.T.A. Hoffmann. Camden House, 2003. ISBN 1571132716

- Ruprecht, Lucia. Dances of the self in Heinrich von Kleist, E. T. A. Hoffman and Heinrich Heine. Ashgate Publishers, 2006. ISBN 0754653617

- Willis, Martin. Mesmerists, monsters, and machines: science fiction and the cultures of science in the nineteenth century. Kent State University Press, 2006. ISBN 0873388577

The following references are cited by the German-language article:

- Braun, Peter. E. T. A. Hoffmann: Dichter, Zeichner, Musiker: Biographie. D/D√ľsseldorf: Artemis und Winkler, 2004. ISBN 3538071756

- Deterding, Klaus. Das allerwunderbarste M√§rchen. Vol. 3 of E.T.A. Hoffmanns Dichtung und Weltbild. D/W√ľrzburg: K√∂nigshausen & Neumann, 20031. ISBN 3826023897

- Deterding, Klaus. Die Poetik der inneren und äußeren Welt bei E. T. A. Hoffmann: Zur Konstitution des Poetischen in den Werken und Selbstzeugnissen. Ph.D. dissertation, Freie Universität Berlin. Berliner Beiträge zur neueren deutschen Literaturgeschichte, 15. D/Frankfurt (Main): Lang, 1991. ISBN 3631440626

- Deterding, Klaus. Hoffmanns poetischer Kosmos. Vol. 4 of E.T.A. Hoffmanns Dichtung und Weltbild D/W√ľrzburg: K√∂nigshausen & Neumann, 20032. ISBN 3826026152

- Deterding, Klaus. Magie des poetischen Raums. Vol. 1, E.T.A. Hoffmanns Dichtung und Weltbild. Beiträge zur neueren Literaturgeschichte, 3rd ser., no. 152. D/Heidelberg: Winter 1999. ISBN 3825305414

- Die Freim√ľthige. Volume II, 6: xxi-xxiv. 1804.

- E. T. A. Hoffmann zur Einf√ľhrung. Zur Einf√ľhrung, no. 166. D/Hamburg: Junius, 1998.

- Ettelt, Wilhelm. E. T. A. Hoffmann: Der K√ľnstler und Mensch. D/W√ľrzburg: K√∂nigshausen & Neumann, 1981. ISBN 3884790315

- Feldges, Brigitte, & Ulrich Stadler, ed. E. T. A. Hoffmann: Epoche ‚Äď Werk ‚Äď Wirkung. D/M√ľnchen: Beck, 1986. ISBN 3406312411

- Fricke, Ronald. Hoffmanns letzte Erz√§hlung: Roman. D/Berlin: R√ľtten und Loening, 2000. ISBN 3352005613

- Götting, Ronald. E. T. A. Hoffmann und Italien. Europäische Hochschulschriften, ser. 1, Deutsche Sprache und Literatur, no. 1347. D/Frankfurt (Main): Lang, 1992. ISBN 363145371X

- Gröble, Susanne. E. T. A. Hoffmann. Universal-Bibliothek, no. 15222. D/Stuttgart: Reclam, 2000. ISBN 3150152224

- G√ľnzel, Klaus. E. T. A. Hoffmann: Leben und Werk in Briefen, Selbstzeugnissen und Zeitdokumenten. D/Berlin: Bibliographie, 1976.

- Harnischfeger, Johannes. Die Hieroglyphen der inneren Welt: Romantikkritik bei E. T. A. Hoffmann. D/Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag, 1988. ISBN 3531120190

- Hoffmann, Alfred. E. T. A. Hoffmann: Leben und Arbeit eines preußischen Richters. D/Baden-Baden: Nomos-Verlag, 1990. ISBN 3789021253

- J√ľrgens, Christian. Das Theater der Bilder: √Ąsthetische Modelle und literarische Konzepte in den Texten E. T. A. Hoffmanns. D/Heidelberg: Manutius-Verlag, 2003. ISBN 393487729X

- Kaiser, Gerhard R. E. T. A. Hoffmann. Sammlung Metzler, no. 243, Realien zur Literatur. D/Stuttgart: Metzler, 1988. ISBN 3476102432

- Keil, Werner. E. T. A. Hoffmann als Komponist: Studien zur Kompositionstechnik an ausgewählten Werken. Neue musikgeschichtliche Forschungen, no. 14. D/Wiesbaden: Breitkopf und Härtel, 1986. ISBN 3765102296

- Klein, Ute. Die produktive Rezeption E. T. A. Hoffmanns in Frankreich. Kölner Studien zur Literaturwissenschaft, no. 12. D/Frankfurt (Main): Lang, 2000. ISBN 3631365357

- Kleßmann, Eckart. E. T. A. Hoffmann oder die Tiefe zwischen Stern und Erde: Eine Biographie. Insel-Taschenbuch, no. 1732. D/Frankfurt (Main): Insel-Verlag, 1995. ISBN 3458334327

- Kohlhof, Sigrid. Franz F√ľhmann und E. T. A. Hoffmann: Romantikrezeption und Kulturkritik in der DDR. Europ√§ische Hochschulschriften, ser. 1, Deutsche Sprache und Literatur, no. 1044. D/Frankfurt (Main): Lang, 1988. ISBN 3820402861

- Kremer, Detlef. Romantische Metamorphosen: E. T. A. Hoffmanns Erzählungen. d/Stuttgart: Metzler, 1993. ISBN 3476009068

- Lewandowski, Rainer. E. T. A. Hoffmann und Bamberg: Fiktion und Realität: Über eine Beziehung zwischen Leben und Literatur. D/Bamberg: Fränkischer Tag, 1995. ISBN 3928648209

- Mangold, Hartmut. Gerechtigkeit durch Poesie: Rechtliche Konfliktsituationen und ihre literarische Gestaltung bei E.T.A. Hoffmann. D/Wiesbaden: Deutscher Universal-Verlag, 1989. ISBN 382444030X

- Meier, Rolf. Dialog zwischen Jurisprudenz und Literatur: Richterliche Unabh√§ngigkeit und Rechtsabbildung in E.T.A. Hoffmanns ‚ÄúDas Fr√§ulein von Scuderi‚ÄĚ. D/Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlags-Gesellschaft, 1994.

- M√©nardeau, Gabrielle ‚ÄúWittkop-‚ÄĚ. E. T. A. Hoffmann: Mit Selbstzeugnissen und Bilddokumenten. Rowohlts Monografien, no. 113. D/Reinbek (Hamburg): Rowohlt, 1992 (original 1966). ISBN 3499501139

- Milovanovic, Marko. ‚Äú‚ÄėDie Muse entsteigt einem Fass‚Äô: Was E.T.A. H. tats√§chlich in Berliner Kneipen trieb.‚ÄĚ 17ff. Kritische Ausgabe 1. 2005. ISSN 1617-1357

- Orosz, Magdolna. Identität, Differenz, Ambivalenz: Erzählstrukturen und Erzählstrategien bei E.T.A. Hoffmann. Budapester Studien zur LIteraturwissenschaft, no. 1. D/Frankfurt (Main): Lang, 2001. ISBN 3631382480

- Ringel, Stefan. Realit√§t und Einbildungskraft im Werk E. T. A. Hoffmanns. D/K√∂ln [‚ÄėCologne‚Äô]: B√∂hlau, 1997. ISBN 3412046973

- Safranski, R√ľdiger. E. T. A. Hoffmann: Das Leben eines skeptischen Phantasten. Fischer-Taschenb√ľcher, no. 14301. D/Frankfurt (Main): Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag, 2000. ISBN 3596143012

- Schaukal, Richard von. E. T. A. Hoffmann: Sein Werk aus seinem Leben. CH/Z√ľrich, D/Leipzig, and A/Wien: Amalthea-Verlag, 1923.

- Schmidt, Dirk. Der Einfluß E.T.A. Hoffmanns auf das Schaffen Edgar Allan Poes. Edition Wissenschaft, Reihe vergleichende Literaturwissenschaft, no. 2. D/Marburg: Tectum-Verlag. 1996.

- Schmidt, Olaf. ‚ÄúCallots fantastisch karikierte Bl√§tter‚ÄĚ: Intermediale Inszenierungen und romantische Kunsttheorie im Werk E. T. A. Hoffmanns. Philologische Studien und Quellen, no. 181. D/Berlin: Schmidt, 2003. ISBN 3503061827

- Schnapp, Friedrich. "Hoffmanns Verwandte aus der Familie Doerffer in K√∂nigsberger Kirchenb√ľchern der Jahre 1740-1811." Mitteilungen der E. T. A. Hoffmann-Gesellschaft. 23 (1977): 1-11.

- Segebrecht, Wulf. Heterogenität und Integration: Studien zu Leben, Werk und Wirkung E. T. A. Hoffmanns. Helicon, no. 20. D/Frankfurt (Main): Lang, 1996. ISBN 3631472021

- Steinecke, Hartmut. Die Kunst der Fantasie: E.T.A. Hoffmanns Leben und Werk. D/Frankfurt (Main): Insel-Verlag, 2004. ISBN 3458172025

- Steinecke, Hartmut. E. T. A. Hoffmann. Universal-Bibliothek, no. 17605. D/Stuttgart: Reclam, 1997. ISBN 3150176050

- Triebel, Odila. Staatsgespenster: Fiktionen des Politischen bei E. T. A. Hoffmann. Literatur und Leben, new ser., no. 60. D/K√∂ln [‚ÄėCologne‚Äô]: B√∂hlau, 2003. ISBN 3412078026

- Weinholz, Gerhard. E. T. A. Hoffmann: Dichter, Psychologe, Jurist. Literaturwissenschaft in der Blauen Eule, no. 9. D/Essen: Verlag Die Blaue Eule, 1991. ISBN 3892064318

- Woodgate, Kenneth B. Das Phantastische bei E. T. A. Hoffmann. Helicon, no. 25. D/Frankfurt (Main): Lang, 1999. ISBN 3631344538

External links

All links retrieved February 12, 2024.

- Works by E.T.A. Hoffmann. Project Gutenberg

- Michael Haldane A translation of Klein Zaches genannt Zinnober

- Das E.T.A.-Hoffmann-Archiv der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin (archive, in German)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.