Joab

Joab (יוֹאָב "The Lord is father," Yoʾav) was a key military leader under King David in the Hebrew Bible in the late eleventh and early tenth centuries B.C.E.. One of David's nephews, he was the military power behind David's throne, winning many crucial battles on David's behalf. For example, he led the charge against the fortress town and David's future capital of Jerusalem; engaged in effective siege tactics against national enemies such as the Edomites, Ammonites, Moabites, and Syrians; and helped put down two serious internal rebellions, including the civil war instigated by David's treacherous son Absalom. He also assisted David in the murder of Uriah the Hittite, the husband of David's lover, Bathsheba.

While Joab's loyalty and courageous leadership won David's trust as commander-in-chief of his armies, he also earned the king's curses for overstepping his authority by assassinating his own rivals against David's wishes. As an old man, Joab himself was finally assassinated at the orders of the newly enthroned King Solomon, following David's death-bed advice. Some of the treasure he had plundered in his military campaigns was so valuable as to be housed in the sacred Temple of Jerusalem that Solomon built, and his descendants remained prominent until after the Jewish exile and return from Babylon.

Biblical Account

Joab hailed from the same Bethlehemite clan as David and was the son of David's older sister, Zeruiah (1 Chronicles 2:16-17). At least two of David's other military commanders hailed from this clan: Abishai and Amasa. The family did military service under King Saul in his battles against the Philistines. However, by the time David and his followers were on the run from Saul, his nephews—specifically Abishai, but likely Amasa and Joab as well—had joined him. When he became king of Judah, David admitted and even lamented the degree to which he relied on Joab and Abishai for his power (2 Samuel 3:39).

Blood feud with Abner

Joab first comes on the scene in the biblical narrative shortly after King Saul has been killed in battle. David rules as king of the Tribe of Judah while Ish-bosheth, son of Saul, rules over the northern tribes in Saul's place as king of "Gilead, Asher, and Jezreel; and also over Ephraim, Benjamin and all Israel." (2 Sam. 2:9) In a moment of apparent peace between the two camps, Joab meets Abner, Ish-Bosheth's general, at the pool of Gibeon. Abner proposes that their men engage in hand-to-hand combat, twelve against twelve. The fighting turns serious, with Joab's men gaining the upper hand. Joab's fleet-footed brother Asahel chases Abner, who does not want to engage him, for fear of creating bad blood with Joab and David. When Asahel refuses to give up the chase, Abner turns and slays him with a spear thrust. Joab's forces pursue Abner to exact vengeance, and the Tribe of Benjamin rallies to Abner's defense. Abner offers a truce, and Joab accepts. The casualties among Joab's forces are counted at 19 missing, while the number of dead among Abner's allies is 360.

Although few details are given concerning the ongoing war between David and Ish-Bosheth, the struggle continued for several years. A major event in David's favor occurs when Abner, King Ish-Bosheth's top military commander, turns traitor and goes over to David's side after a scandal involving his alleged affair with the concubine of Ish-Bosheth's father, Saul (2 Sam. 3). As proof of Abner's good faith, David demands that he bring with him Michal, the daughter of Saul, who had been David's first love and young wife, but had later been given by Saul to another man. The fearful Ish-Bosheth allows both Michal and Abner to leave. Abner comes then to David at his capital of Hebron, bringing not only Michal, but also 20 soldiers and a pledge of loyalty from the entire Tribe of Benjamin, as well as elements of other northern tribes who have lost faith in Ish-Bosheth's leadership. David then dispatches Abner north to garner additional support for David's cause.

Joab, learning of Abner's visit to Hebron, immediately sends messengers to recall him. When Abner dutifully returns, Joab stabs him in the stomach and kills him, ostensibly "to avenge the blood of his brother Asahel," but no doubt because he also senses in Abner a threat to his own position. David publicly declares himself innocent of the crime, cursing Joab's family and ordering him to publicly repent for the murder. However he does not demote Joab or otherwise punish him for his act. Ish-Bosheth, meanwhile, would soon be assassinated. Although David benefits greatly from this act, he again disassociates himself from it, and orders the assassins to be executed (2 Sam. 4).

Commander of David's armies

With Ish-Bosheth out of the way, David is able to consolidate power and soon becomes the monarch of what history calls the United Kingdom of Israel and Judah. Joab leads the forces that take the Jebusite fortress of Jerusalem. According to the account in Chronicles, it was this act that moved David to name Joab his commander-in-chief. This account also credits Joab with restoring the existing city of Jerusalem after its capture, while David "built up the city around it, from the supporting terraces to the surrounding wall." (I Chon. 6-8)

Thereafter, Joab helps David to win major crucial victories against the Philistines, Moabites, Syrians, and Edomites. (2. Sam. 8) With his brother Abishai, Joab also wins a brilliant victory against a combined Ammonite and Syrian force, after which Ammon becomes a vassal state of David's kingdom (2 Sam. 10).

During the Israelite siege of the Ammonite town of Rabbah, one of the commanders under Joab is the warrior Uriah the Hittite, the unknowing husband of David's lover Bathsheba. During the long siege, Bathsheba becomes pregnant and Uriah is suddenly recalled to Jerusalem in order that David can claim that Uriah had been with Bathsheba at a plausible time of conception. When this plan is foiled by Uriah's soldierly refusal to stay at his home with Bathsheba while his men fight on the front line, Uriah soon returns to Joab with a sealed message. Joab reads David's orders with what must have been shock:

- "Put Uriah in the front line where the fighting is fiercest.

- Then withdraw from him so he will be struck down and die."

Joab dutifully does as David instructs, and the innocent Uriah dies when Joab's men leave him unprotected in harm's way. After ensuring victory by seizing the town's water supply, Joab sends news to David, allowing his uncle and king the glory of conquering the city and receiving its king's crown. A series of easy military victories over other Ammonite towns quickly follows (2 Sam. 2:12).

Joab and Absalom

Joab also plays a key role in the drama of David's son Absalom. The charismatic heir-apparent to David's throne, Absalom had slain his half-brother Amnon after Amnon had raped Absalom's sister Tamar. Absalom was widely popular not only for his handsome appearance and winning personality but also for punishing the criminal when his father had been unwilling to act. For three years, David remains in a state of despondency over the matter. It is not until Joab conspires with a "wise woman" of Tekoa to manipulate David psychologically that the king finally comes to himself and allows Absalom to return. After two more years, with Absalom back in Jerusalem but still banished from the king's presence, it is Joab—under serious pressure from Absalom—who facilitates a reconciliation between them (2 Sam. 15).

Within three years, however, Absalom has gained enough support to mount a serious rebellion against David, causing the king to abandon Jerusalem as Absalom approaches from Hebron with "all the men of Israel." (2 Sam. 16:15) Joab, perhaps demoted by David on account of his earlier support of Absalom, is placed in charge of one third of David's forces, another third being given each to Joab's brother Abishai and a Philistine ally of David's named Ittai. Still unwilling to act decisively, David gives orders that, in the fighting, Absalom must not be intentionally harmed.

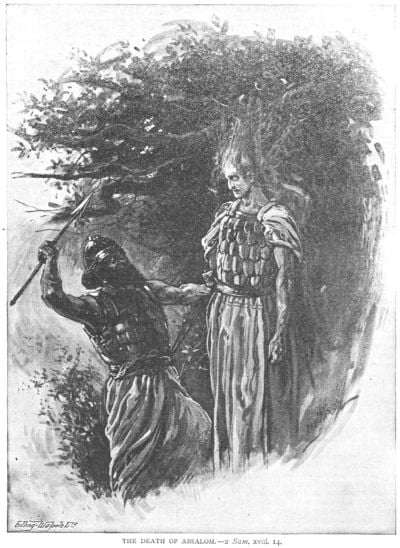

It is soon reported to Joab that Absalom's had been caught in a tree by his long hair as he rode past on horseback. Joab promptly finds and slays the helpless Absalom with javelins. David, rather than celebrating the victory for which his troops had risked their lives, pitifully mourns Absalom's death until Joab courageously confronts him, saying:

- "Today you have humiliated all your men, who have just saved your life and the lives of your sons and daughters and the lives of your wives and concubines. You love those who hate you and hate those who love you… Now go out and encourage your men. I swear by the Lord that if you don't go out, not a man will be left with you by nightfall." (2 Sam 19:5-7)

Once again coming to his senses only through Joab's intervention, David immediately goes out and takes his public place among his men. On his return to Jerusalem, however, David allows Amasa—his nephew who had led the army under Absalom—to remain in the position of commander-in-chief.

Later career

Soon, David faces another rebellion of the northern tribes under the leader Sheba son of Bicri. David places Amasa in charge of the expedition to put down the rebels. When Amasa delays in mustering adequate troops, the king sends Abishai and Joab ahead, with Abishai now in command. When Amasa joins them, Joab takes the opportunity to slay him. He and Abishai then rally the troops and pursue the rebel Sheba to the town of Abel Beth Maacah, where the armies of Judah again use siege tactics to force the rebels to capitulate. Here, Joab once again employs a "wise woman" who agrees to use her influence to betray Sheba in exchange for the lifting of the siege. Soon, the head of Sheba is thrown down from the town's wall, and the siege is lifted. Immediately, a narrator tells us that Joab is again "over Israel's entire army." (2 Sam. 20:23)

Later, Joab balks when David commands him to take a census of the nation's able-bodied men, believing that such a thing would constitute a sin. David insists, and Joab leads a mission of almost 10 months, going throughout the country to enroll them all. On his return, Joab reports 800,000 able-bodied men who could handle a sword among the northern tribes and another 500,000 in Judah. The account in Chronicles gives slightly different numbers, adding: "Joab did not include Levi and Benjamin in the numbering, because the king's command was repulsive to him." (1 Chronicles 21:6)

Realizing his sin, David repents for commanding the census. Nevertheless, God reportedly strikes the land with a plague, which ends only after David purchases land from Araunah the Jebusite, builds an altar there, and offers various sacrifices (2 Sam. 24).

Joab's demise and legacy

Near the end of David's life, Joab miscalculates badly when he, together with the high priest Abiathar, supports the heir-apparent, Adonijah, in his bid to have himself named king while David is still clinging to life. While Adonijah, Abiathar, Joab, and several of the royal sons participate in a sacrificial feast nearby, Bathsheba and the prophet Nathan conspire to have Bathsheba's son Solomon named king by portraying Adonijah as a usurper. David immediately commands Nathan and another priest, Zadok, to anoint Solomon as his successor (1 Kings 1).

On his deathbed David advises Solomon to act ruthlessly in consolidating power, especially toward Joab, remembering Joab's murders of Abner and Amasa. "Do not let his gray head go down to the grave in peace," David commands (1 Kings 2:6). Solomon moves against Adonijah and Joab after Adonijah's bold request to take David's young former concubine, Abishag, as his wife. Solomon has Adonijah assassinated immediately and exiles Abiathar to his home village of Anathoth. Joab seeks sanctuary at the sacred altar of the "tent of the Lord." Solomon then commands his man, Benaiah, son of Jehoiada, to strike down Joab where he stands, justifying the act on account of "the innocent blood that Joab shed." Benaiah does as he was ordered. Thus Joab dies clinging to the horns (horn-shaped front-posts) of the altar. Solomon rewards Benaiah by placing him in charge of the army in Joab's former place, while Zadok, who helped Solomon to the kingship, is made high priest. Joab is buried in a tomb on his own property.

The Book of Chronicles adds the interesting note that Joab dedicated certain items of plunder that were considered holy enough to be placed in the Temple of Jerusalem after it was built (1 Cron. 26:28). Joab's family apparently remained prominent after his death for many generations, as the Book of Ezra lists 219 descendants of Joab, including their leader, Obadiah son of Jehiel, as returning from Babylon to Jerusalem after their exile. The scribal introduction to Psalm 60 preserves a tradition that this hymn was written on the occasion of Joab's victory over the Edomites in the Valley of Salt.

Rabbinical Tradition

The rabbis of the Babylonian Talmud hotly debated the character of Joab. Rabbi Abbah ben Kahana saw him as a great warrior without whom King David would not have been a truly great man. "If not for Joab," said Rabbi Abbah, "David would not have been able to occupy himself with the law." Said Rabbi Jehudah, the character of Joab's house was extremely righteous. "As a desert is free of robbery and adultery, so was the house of Joab." Rabbi Jehudah also affirmed Joab's generosity to the people of Jerusalem, whom he had recently conquered. "Joab supplied to the poor of that city everything to which they were accustomed." Because Solomon had Joab killed in a sacred sanctuary, Rabbi Jehudah held that all the curses with which David earlier doomed Joab fell on the descendants of David.

Other rabbis, however, view Joab as a criminal. For killing Abner, Joab was brought before a court. He answered that he was the avenger of the blood of his brother Asahel. Asked why he killed Amasa, Joab replied: "He was a rebel to the king." These answers, however are not considered convincing. He is also criticized for his complicity in David's murder of Uriah and for his support of Adonijah's attempt to usurp the throne.

Critical View

Archaeologists today doubt that David's kingdom could have been as far-flung as suggested in the biblical account. For example, according to Israel Finkelstein (2006), evidence indicates that David's capital of Jerusalem was little more than a village in the late eleventh century B.C.E., and the population centers in the rest of Judah and Israel were not major cities, but towns at best. The grand scale of Joab's military conquests may therefore have been as exaggerated as the description of David's kingdom itself.

This does not rule out that Joab was a historical character or the military genius who helped David maintain and extend his rule, however. Indeed, a close reading of the Joab narrative contains much information that challenges the conventional impression that David himself personally led most of "his" military victories. While Joab leads the siege of Rabbah, we see David at home in his palace, so bored with life that even his large harem does not satisfy him; and thus he commits adultery with the wife of Joab's lieutenant Uriah. As is often the case, Joab does David's "dirty work" by seeing to the murder of Uriah, while David seeks to make himself look innocent of wrongdoing. Only after Joab ensures victory does David ride out of his palace to claim the glory. Later we see David brooding in depression for years while Absalom remains estranged, ironically for acting much like Joab does—in taking action against a criminal (Amnon) whom David is too weak to punish. Later still, when David for once takes to the field with his troops, he is so absorbed in mourning Absalom that he cannot even join them in celebrating their victory, and once again Joab must come to his rescue. Indeed, one cannot help but wonder if it is primarily Joab's slaying of Absalom—rather than his murder of Abner and Amasa—that causes David, on this deathbed, to conspire with Solomon against Joab.

As is often the case, the account in the books of Samuel and Kings give more embarrassing details about David and Joab than does the account in Chronicles, which omits the murder of Uriah, as well as Joab's allowing David the glory at the battle of Rabbah, and Joab's several rescues of David from the throes of depression and indecision. Biblical scholars often view the criterion of the "embarrassment" of a major figure such as David as tending to authenticate the historicity of certain biblical passages. The possibility of the heroic tradition of Joab existing as an independent one, later woven into the account, has also been suggested.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bright, John. A History of Israel, 4th edition. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2000. ISBN 0664220681

- Finkelstein, Israel. David and Solomon: In Search of the Bible's Sacred Kings and the Roots of the Western Tradition. Free Press, 2006. ISBN 0743243625

- Galil, Gershon. The Chronology of the Kings of Israel and Judah. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers, 1996. ISBN 9004106111

- Grant, Michael. The History of Ancient Israel. NY: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1984. ISBN 0684180812

- Keller, Werner. The Bible as History. NY: Bantam, 1983. ISBN 0553279432

- Miller, J. Maxwell. A History of Ancient Israel and Judah. Louisville KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1986. ISBN 066421262X

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.