| Books of the |

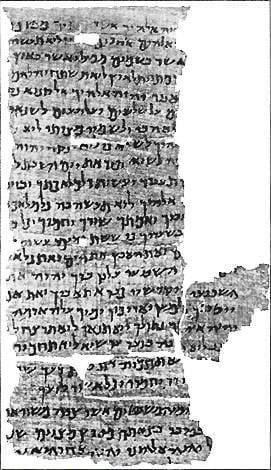

The Book(s) of Chronicles are part of the Hebrew Bible and Christian Old Testament. In the Hebrew version, it often appears as the last book of the Ketuvim, or Writings, also making it the final book of the Jewish scripture. Chronicles largely parallels the narratives in the Books of Samuel and the Books of Kings, although it emphasizes the southern Kingdom of Judah almost exclusively, while the earlier books concentrate on the northern Kingdom of Israel as well.

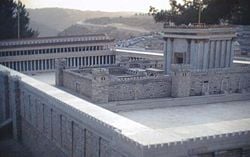

The author of Chronicles, termed "the Chronicler," may also have written Ezra-Nehemiah. His work is an important source of information supplementing the earlier historical books of the Hebrew Bible. Moreover, it served to inspired the Jews returning from the Babylonian Exile with a view of history inspiring them to center their lives on the Temple of Jerusalem, the Law of Moses, and the hope of a renewal of the Davidic kingship in the person of the Messiah.

Overview

In the original Hebrew, the book was entitled Divrei Hayyamim, ("matters [of] the days") based on the phrase sefer divrei ha-yamim le-malkhei Yehudah ("book of the days of the kings of Judah"). In the Greek Septuagint version (LXX), Chronicles bears the title Paraleipomêna tōn basileōn Iouda ("miscellanies concerning the kings of Judah") because it contains details not found in the Books of Samuel and the Books of Kings. Jerome, in his Latin translation of the Bible (Vulgate), titled the book Paralipomenon, since he believed it to represent the "chronicle of the whole of sacred history."

In the Herbrew Masoretic text, Chronicles is part of the third section of the Tanakh, the Ketuvim, or "Writings." It is located as the last book in in this section, following the books of Ezra and Nehemiah. Since the books of the Prophets come before the Writings, this makes Chronicles the final book of the Hebrew Bible in most Jewish traditions.

In Christian Bibles, however I and II Chronicles are part of the "Historical" books of the Old Testament, following the Books of Kings and before the Book of Ezra. This order is based upon that found in the Septuagint, also followed by the Vulgate, and relates to the view of Chronicles as a "supplement" to Samuel and Kings.

The division of the book into two parts is arbitrary, probably having to do with the need to separate its lengthy context into two or more scrolls. Chronicles is a single book in the Masoretic textual tradition. In the earlier Septuagint, however, the book appears in two parts. The Septuagint's division of the book was followed in the Christian textual tradition. Thus, in modern Christian bibles, Chronicles is usually published as two books: I Chronicles and II Chronicles. The two-part division began to be noted in Hebrew Bibles in the fifteenth century, for reference purposes. However, most modern editions of the Bible in Hebrew publish the two parts together as a single book.

The book represents a summary of the entire span of providential history, from the dawn of time to the time of its composition. Thus, the Chronicler's first of many genealogical tables is traced back to Adam. Its focus, however, is on the history of the Kingdom of Judah, the home of the Temple of Jerusalem, which forms the central object of the Chronicler's concern as the repository of Jewish tradition centering on the Law of Moses.

Outline

The Books of Chronicles may be divided into the following four parts:

- The beginning (chapters 1-10) mostly contains genealogical lists, concluding with the House of Saul and Saul's rejection by God, which sets the stage for the rise of David.

- The remainder of I Chronicles (chapters 11-29) is a history of David's reign, concluding, with the accession of Solomon.

- The beginning of II Chronicles (chapters 1-9) is a detailed history of the reign of King Solomon as a Golden Age of peace and unity, including the building of the Temple of Jerusalem, Solomon's prayer, his vision, sacrifices, glory and death.

- The remainder of II Chronicles (chapters 10-36) is an account of the kings of Judah to the time of the Babylonian exile, and concluding with the call by Cyrus the Great for the exiles to return to their land.

Composition

The time of the composition of Chronicles is believed to have been subsequent to the Babylonian Exile, probably between 450 and 435 B.C.E. or later. The close of the book records the proclamation of Cyrus the Great permitting the Jews to return to their own land, and also this forms the opening passage of the Book of Ezra, which may be viewed as a continuation of the Chronicles, together with the Book of Nehemiah.

According to Jewish tradition, Ezra, the high priest and scribe, was regarded as the author of Chronicles. There are many points of resemblance between Chronicles and the Book of Ezra which seem to confirm that Ezra and Chronicles were written by the same person, even if this may not have been the famous priest himself.

In its general scope and design Chronicles is not so much historical as religious. The Jewish Encyclopedia characterizes it as "A history of the Temple and its priesthood, and of the house of David and the tribe of Judah, as guardians of the Temple." [1] The principal aim of the writer is to present moral and religious truth. He gives less prominence to political occurrences than do the authors of Samuel and Kings, and treats the northern Kingdom of Israel more as an enemy nation than a member of the Covenant community, as the author of Kings does. The writer provides details of the Temple service and long lists of names of leading priests and Levites, which are absent in the earlier histories. Other genealogies also play a prominent role in the text.

In addition to the books of Samuel and Kings, the sources from which the chronicler compiled his work were public records, registers, and genealogical tables belonging to the Jews who returned from Babylon to Judea. These are referred to frequently in the course of the book. Sections of Samuel and Kings are often copied verbatim.

Updating Samuel and Kings

Many scholars believe that the author of Chronicles intended it to replace the earlier histories recorded in Samuel and Kings. Chronicles omits many particulars recorded in these early works (2 Sam. 6:20-23; 9; 11; 14-19, etc.) and includes many things peculiar to itself (1 Chr. 12; 22; 23-26; 27; 28; 29, etc.). Besides the above-mentioned emphasis on the priesthood and genealogical records, Chronicles paints a more positive picture of certain events, and a more negative one of others, than does Samuel and Kings.

David and Solomon

For example, in the life of David Chronicles omits the embarrassing details of David's sin with Bathsheba, his murder of Uriah the Hittite, his denunciation by the prophet Nathan, and the consequent death of Bathseba's first son, the child of her and David's adultery (2 Sam. 11-12). Nor does the Chronicler see fit to mention David's civil war with Ish-bosheth, the rape of David's daughter Tamar by her half-brother Amnon (2 Sam. 3), the nearly-successful rebellion of David's son Absalom (2 Sam 15-18), or the attempt of Adonijah to usurp the throne in David's old age (1 Kings 1).

Solomon's reign is likewise painted in golden tones. Although he has many foreign wives, his sin of building high places for their deities is not mentioned in Chronicles. Nor does the prophet Ahijah appear to call Jeroboam I, as a result of Solomon's sin, to revolt against Solomon's son and establish the northern tribes as a separate kingdom, as told in 1 Kings 11.

Southern emphasis

Indeed, Chronicles ignores much of the history of the northern Kingdom of Israel, mentioning northern kings only insofar as they interact with the kings of Judah. Not only is the prophetic endorsement of Jeroboam I missing, even his infamous sin of establishing the golden calves at Bethel and Dan—a constant theme in Kings—goes virtually unnoticed. Likewise, the stories of northern prophets such as Elijah and Elisha, which provide some of the most dramatic moments of the Books of Kings, are absent from Chronicles.

On the other hand, the southern king Jehoshaphat, treated with less tepid enthusiasm in the Books of Kings (1 Kings 22) because of his alliance with the King Ahab of Israel, emerges in Chronicles as a heroic reformer who did much to promote the monotheistic tradition. Chronicles adds, however, Jehoshaphat sinned near the end of his reign, receiving a prophetic rebuke: "Because you have made an alliance with Ahaziah, the Lord will destroy what you have made" (Chron. 20:27). In Kings, on the other hand, the prophet Elisha had expressed God's support of Jehoshaphat's alliance with Israel against the Moabites (2 Kings 3).

Another example of Chronicles' more differing attitude toward certain kings, is that of Hezekiah. This king is praised by both Kings and Chronicles, but the Chronicler lauds him as the initiator of Passover as a national holiday, an honor granted by the author of Kings not to Hezekiah but Josiah. Similarly, while Kings relates a story of the prophet Isaiah delivering a dire oracle against Hezekiah because of his foolishly showing his treasures to visiting Babylonian envoys—implying that his action will result in Judah's exile—Chronicles ignores this incident entirely.

Manasseah and Josiah

A particularly interesting case in point is the differing attitudes of Chronicles and Kings regarding Hezekiah's son, Manasseh. In Kings, Manasseh is an absolutely evil ruler, but in Chronicles, he repents in his later years and returns to God. Kings declares Manasseh to be the cause of the ultimate destruction of the Kingdom of Judah by the Babylonian Empire, saying: "Surely these things happened to Judah according to the Lord's command, in order to remove them from his presence because of the sins of Manasseh and all he had done" (2 Kings 24:2-3).

Chronicles, on the other hand, takes the view that when Manasseh repented for his sins, God was moved to forgiveness and mercy; and that Manasseh instituted a monotheistic reform as a result:

In his distress he sought the favor of the Lord his God and humbled himself greatly before the God of his fathers. And when he prayed to him, the Lord was moved by his entreaty and listened to his plea; so he brought him back to Jerusalem and to his kingdom. Then Manasseh knew that the Lord is God... He got rid of the foreign gods and removed the image from the temple of the Lord, as well as all the altars he had built on the temple hill and in Jerusalem; and he threw them out of the city. Then he restored the altar of the Lord and sacrificed fellowship offerings and thank offerings on it, and told Judah to serve the Lord, the God of Israel (2 Chronicles 33:12-15).

Another case in point regards the death of King Josiah. In Kings, Josiah is the greatest king since David and does no wrong whatsoever. His death is attributed to the sins of his grandfather Manasseh. The notice of Josiah's death reads: "While Josiah was king, Pharaoh Neccho II Neco king of Egypt went up to the Euphrates River to help the king of Assyria. King Josiah marched out to meet him in battle, but Neco faced him and killed him at Megiddo" (2 Kings 23:21).

In Chronicles, however, Josiah's death is explained as resulting from his sin in not listening to the Pharaoh, who did not wish to engage Josiah.

Neco sent messengers to him, saying, "What quarrel is there between you and me, O king of Judah? It is not you I am attacking... God has told me to hurry; so stop opposing God, who is with me, or he will destroy you." Josiah, however, would not turn away from him, but disguised himself to engage him in battle. He would not listen to what Neco had said at God's command but went to fight him on the plain of Megiddo. Archers shot King Josiah... So they took him out of his chariot, put him in the other chariot he had and brought him to Jerusalem, where he died (2 Chron 35 22-24).

Other changes

Chronicles also records many things in fuller detail than the books of Samuel and Kings, such as the list of David's heroes (1 Chr. 12:1-37), the removal of the Ark from Kirjath-jearim to Mount Zion (1 Chr. 13; 15:2-24; 16:4-43; comp. 2 Sam. 6), King Uzziah's "leprosy" (2 Chr. 26:16-21; comp. 2 Kings 15:5), and the details of the reigns of several of Judah's kings.

Another characteristic of the book is that it substitutes more modern expressions for older terms that had then become unusual or obsolete. This is seen particularly in the substitution of modern names of places, such as were in use in the writer's day, for the old names; thus Gezer (1 Chr. 20:4) is used instead of Gob (2 Sam. 21:18).

Finally, in keeping with its tendency to omit embarrassing details found in its sources, Chronicles also attempts to resolve some troubling details mentioned by earlier works. For example, where Samuel states David's sin in conducting a military census was caused by God (2 Samuel 24:1), Chronicles states that it was motivated by Satan (1 Chronicles 21:1). And while Samuel—apparently contradicting its own more famous story—attributes the slaying of the giant Goliath to a solider in David's army called Elhanan (2 Samuel 21:19), Chronicles states that Elhanan did not kill Goliath, but another giant named Lahmi, who was Goliath's brother (1 Chron. 20:5).

Critical view

The books of Samuel and Kings were probably completed during the Babylonian Exile, having been compiled from earlier sources which viewed the people of the northern kingdom as sharers with them in the covenant of God with Jacob and Moses. Chronicles was written considerably later. If it was indeed written by the same hand as the Book of Ezra, then its author had come to believe that the inhabitants of the north—who had intermarried with Assyrian immigrants and impermissibly employed non-Levite priests at unauthorized altars—had no part in the Jewish tradition. For him, the northern tribes were truly "lost," and recounting the details of their history was unnecessary. He shares and even expands upon the Deuteronomic historian's[2] concern for the Temple of Jerusalem. However, he no longer hopes for or even desires the repentance of the northern tribes.

Indeed, the Chronicler adopts toward the northern tribes an attitude similar to that expressed by the governor of Judea, Zerubbabel, in the immediate post-exilic period. The neighboring peoples had offered: "Let us help you build because, like you, we seek your God and have been sacrificing to him since the time of Esarhaddon king of Assyria." Zerubbabel rebuffed these fellow worshipers of Yahweh as enemies, saying: "You have no part with us in building a temple to our God. We alone will build it for the Lord, the God of Israel," (Ezra 4:2-3).

Chronicles, Ezra, and Nehemiah may once have been a single work.[3] Critical scholars tend to dismiss the idea of Ezra as the work's author, because internal evidence suggest the writer lived well after Ezra's time. For example, descendants of Zerubbabel (I Chron. iii. 24) are listed to the sixth generation (about 350 B.C.E.) in the Masoretic text and in the Septuagint and Vulgate, to the eleventh generation (about 200 B.C.E.).

Notes

- ↑ Chronicles, Books of. www.jewishencyclopedia.com. Retrieved June 21, 2007.

- ↑ This figure is thought to be the compiler of the books of Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings, as well as the probable author of Deuteronomy, working during the reign of King Josiah around 600 B.C.E.

- ↑ Ibid.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bright, John. A History of Israel. Louisville KY: Westminster John Knox Press; 4th edition, 2000. ISBN 0664220681

- Dever, William G. What Did the Biblical Writers Know and When Did They Know It?: What Archaeology Can Tell Us About the Reality of Ancient Israel. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2002. ISBN 9780802821263

- Galil, Gershon. The Chronology of the Kings of Israel and Judah. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers, 1996. ISBN 9004106111

- Grant, Michael. The History of Ancient Israel. New York: Charles Srcibner's Sons, 1984. ISBN 0684180812

- Keller, Werner. The Bible as History, New York: Bantam, 1983. ISBN 0553279432

- Miller, J. Maxwell. A History of Ancient Israel and Judah. Louisville KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1986. ISBN 066421262X

This entry incorporates text from the public domain Easton's Bible Dictionary, originally published in 1897.

External links

All links retrieved December 10, 2023.

- Catholic Encyclopedia article. www.newadvent.org.

Jewish translations:

- Divrei Hayamim I - Chronicles I (Translation with Rashi's commentary). www.Chabad.org.

- Divrei Hayamim II - Chronicles II (Translation with Rashi's commentary). www.Chabad.org.

| |||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.