Bel and the Dragon

Bel and the Dragon is an apocryphal Jewish story which appears as chapter 14 of the Septuagint Greek version of the Book of Daniel and is accepted as scripture by some Christians, though not in Jewish tradition. The story is not primarily about either the god Bel or the dragon, but relates several legends about the prophet Daniel, who defeats the priests of Bel in one episode, then kills a dragon whom the Babylonians believe is a god, and finally is cast once again into the famous lion's den, where he receives a miraculous visit from the Judean prophet, Habukkuk.

Bel and the Dragon and other deuterocanonical books were included by the Alexandrian Jews in their Greek translation of the Jewish scriptures, known as the Septuagint. However, these legends were not accepted by the Jews of Jerusalem or later rabbinical authorities. Thus, Bel and the Dragon does not appear in the Hebrew Bible. Catholic and Orthodox Bibles do include the stories as part of the Book of Daniel, but Protestant Bibles usually omit them.

As a literary genre, the story of Daniel and the priests of Bel is the first known example of a "locked room" mystery, with Daniel in the role of detective.

Summary

Bel and Dragon consists of two or three independent narratives, which place the hero-prophet Daniel at the court of Cyrus, the Persian king of Babylon near the end of the Babylonian exile of the Jews. There, Daniel "was a companion of the king, and was the most honored of all his friends" (14:1).

Daniel and the priests of Bel

The narrative of priests of Bel, the king asks Daniel, "Do you not think that Bel is a living god? Do you not see how much he eats and drinks every day?" To this, Daniel answers that the idol is made of clay covered with bronze and thus, cannot eat or drink.

Enraged, the king then demands that the 70 priests of Bel show him that Bel truly consumes the offerings made to him. The priests then suggest that the king set the offerings as usual, consisting of "12 great measures of fine flour, and 40 sheep, and six vessels of wine," and then seal the entrance to the temple with his signet ring. If Bel does not consume the offerings, the priests are to be sentenced to death; otherwise, it is Daniel who will be killed.

Using a detective technique that would later be repeated in many mystery stories involving sealed rooms, Daniel cleverly scatters ashes over the whole perimeter of the temple in the presence of the king after the priests have left. The next morning, Daniel calls attention to footprints on the temple's floor. In fact, the sacred meal of Bel has been consumed at night by the priests and their families, who entered through a secret door after the temple's doors were sealed. The priests of Bel are arrested and confess their deed. They and their families are put to death, and Daniel is permitted to destroy both the idol of Bel and its temple.

Daniel and the dragon

In the brief companion narrative of the dragon, the text relates that "there was a great dragon, which the Babylonians revered." In this case the supposed god is no idol, but a living being, supposed by the Babylonians to be an eternal deity. This time, Daniel exposes the folly of worshiping a mere creature by proving its mortality. He rakes pitch, fat, and hair together to make cakes that, when eaten, cause the dragon to burst open, apparently from indigestion. In variant versions, other ingredients serve the same purpose.

The Babylonians, however, grow indignant. "The king has become a Jew; he has destroyed Bel and killed the dragon, and slaughtered the priests," they say. They demand that Daniel be handed over to them, or else the king will be killed. They then seize Daniel and imprison him in a lions' den where he stays for six days.

Daniel, Habakkuk, and the lions

The Septuagint version precedes this part of the story with the notice: "From the prophecy of Habakkuk, son of Yeshua, of the tribe of Levi." This incident thus appears to have been inserted into the narrative of Daniel's second visit to the lion's den, which then concludes after the story of Daniel and Habakkuk. The story suddenly shifts to Judea, where the prophet Habakkuk is busy mixing some bread in a bowl, together with a stew that he had broiled as a lunch for the reapers working in his fields. Unexpectedly, an angel appears and commands him to take the meal to Daniel in the lions' den at Babylon. "Babylon, sir, I have never seen," replies the prophet, "nor do not know the den!"

The angel then seizes the prophet by the hair and carries him to Babylon. "Daniel, Daniel," cries Habakkuk, "take the lunch God has sent you." Daniel thanks him, expresses his gratitude to God, and Habakkuk immediately departs back to Babylon with the angel.

After the seven days are up, the king rejoices to learn that his friend remains unharmed, declaring: "You are great, O Lord, the God of Daniel, and there is no other besides you!" He then causes those who had demanded Daniel's death to be placed in the den, where they are promptly devoured.

Purpose, origin, and texts

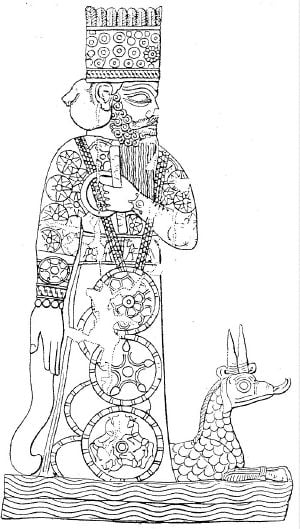

The purpose of these whimsical stories is to ridicule idol-worship and to extol the power of God, who preserves his faithful servants in all perils. Bel was an important figure of Babylonian idolatry as depicted in (Isaiah 45:1 and Jer. 51:44). The term is the Akkadian equivalent of the Semitic word baal, meaning "lord." In Babylonian texts it was often applied to the storm god Marduk, the chief deity of Babylon, who was indeed the primary god worshiped by Cyrus the Great.

The dragon, meanwhile, was sacred to Marduk. The way in which Daniel destroys the dragon is seen by some commentators as similar to Marduk's destruction of Tiamat in the Babylonian creation myth Enuma Elish, by driving a storm-wind into her and rending her asunder. Some scholars have suggested that the word for "pitch," which Daniel feeds to the dragon, may derive from an older term meaning "storm-wind." In another sense, Daniel destruction of the dragon stands for Yahweh's victory over the primordial serpent, called Rahab and Leviathan in the Bible, a theme which occurs several times in the post-exilic Jewish literature.

How the prophet Habakkuk came to be introduced into the story probably can be best explained with reference to now lost legends relating to the two prophets, one of which has found its way into the text. The second lion's den story into which Habakkuk intrudes is probably a variant of the better known one.

Two versions of Bel and the Dragon have survived, one in Greek, the other in Aramaic; and the Greek work exists in two recensions: That of the Septuagint and that of Theodotion, a Hellenistic Jewish writer of the late second century C.E. In the Septuagint, Daniel is called a priest, the son of Habal, and is introduced as a person previously unknown. The name of the king of Babylon, whose friend he was, is not given in this version; and a prophecy of Habakkuk is included. In Theodotion's version, the king is identified as Cyrus, Daniel is not called a priest, and nothing is said of a prophecy of Habakkuk.

Canonicity

The stories of Daniel's contest against the priests of Bel, his adventure with the Babylonian dragon-god, and his second adventure in the lion's den are part of the so-called "additions to Daniel," comprising three chapters of the book not found in the Hebrew/Aramaic text. The additions are:

- The Prayer of Azariah and Song of the Three Holy Children: Daniel 3:24-90 inserted between verses 23 and 24 (v. 24 becomes v. 91) in the Protestant cannon. It also incorporates the "fiery furnace" episode.

- Susanna and the Elders: inserted before Daniel 1:1 as a prologue in early Greek manuscripts; chapter 13 in the Vulgate.

- Bel and the Dragon: after Daniel 12:13 in Greek, but placed as an epilogue, chapter 14, in the Vulgate.

These traditions appear to have been regarded by the ancient Jewish community of Alexandria, Egypt, as belonging in the class of sacred writings, since they were included in the Greek Septuagint version of the Hebrew scriptures produced there. However, the additions were not regarded as scripture by the Palestinian Jewish leaders. They were, thus, not included in the canon of the Hebrew Bible.

Because the Septuagint, being in Greek, was the Bible of choice of most Christians, the additions to the Book of Daniel came to be more influential in the Christian tradition. Bel and the Dragon is quoted as the work of the prophet Daniel by Tertullian and other early Christian writers, and its claim to canonicity is defended by Origen (Epistola ad Africanum). Together with the other additions to Daniel, it was eventually accepted into the Catholic and Orthodox canons. In modern times, it continues to be as part of the Book of Daniel in the Roman Catholic, Greek Orthodox, and Oriental Orthodox churches, but is generally excluded by Protestants.

See also

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bullard, Roger Aubrey, and Howard Hatton. A Handbook on the Shorter Books of the Deuterocanon. New York: United Bible Societies, 2006. ISBN 9780826702012.

- DiTommaso, Lorenzo. The Book of Daniel and the Apocryphal Daniel Literature. Leiden: Brill, 2005. ISBN 9789004144125.

- Liebman, Arthur. Thirteen Classic Detective Stories; A Critical History of Detective Fiction. New York: Richards Rosen Press, 1974. ISBN 9780823902903.

- Moore, Carey A. Daniel, Esther and Jeremiah: The Additions. New Haven: Anchor Yale Bible, 2007. ISBN 9780300140002.

This article incorporates text from the public domain Jewish Encyclopedia (1906)

External links

All links retrieved September 26, 2023.

- Bel and the Dragon: text and resources. earlyjewishwritings.com

- Jewish Encyclopedia article on Bel and the Dragon. jewishencyclopedia.com

| |||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.