| Ancient Mesopotamia |

|---|

| Euphrates – Tigris |

| Assyriology |

| Cities / Empires |

| Sumer: Uruk – Ur – Eridu |

| Kish – Lagash – Nippur |

| Akkadian Empire: Akkad |

| Babylon – Isin – Susa |

| Assyria: Assur – Nineveh |

| Dur-Sharrukin – Nimrud |

| Babylonia – Chaldea |

| Elam – Amorites |

| Hurrians – Mitanni |

| Kassites – Urartu |

| Chronology |

| Kings of Sumer |

| Kings of Assyria |

| Kings of Babylon |

| Language |

| Cuneiform script |

| Sumerian – Akkadian |

| Elamite – Hurrian |

| Mythology |

| Enûma Elish |

| Gilgamesh – Marduk |

| Mesopotamian mythology |

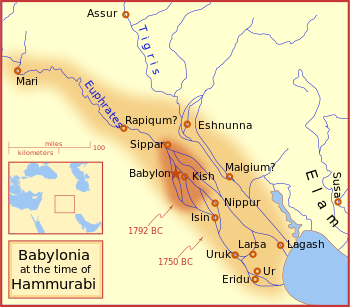

Babylonia, named for its capital city of Babylon, was an ancient state in Mesopotamia (in modern Iraq), combining the territories of Sumer and Akkad. The earliest mention of Babylon can be found in a tablet of the reign of Sargon of Akkad, dating back to the twenty-third century B.C.E. It became the center of empire under Hammurabi (c. 1780 B.C.E. and again under Nebuchadnezzar II (reigned 605–562 B.C.E.). Fabled for the beautiful hanging gardens, Babylon was the capital of an ancient civilization that helped to bridge several cultural spheres from Africa to Asia Minor, thus aiding the spread of technology and trade.

In the Judeo-Christian tradition, the neo-Babylonian empire ruler Nebuchadnezzar II destroyed the Temple of Jerusalem and took the Israelites into exile; this was viewed by the prophet Jeremiah as God's chastisement. Babylon became a biblical symbol of corrupt power and wealth, an image of exile and oppression (Isaiah 47:1-13; Revelation 17:3-6). The yearning for their homeland expressed in Psalm 137 has been echoed by refugees and exiles of every age:

By the waters of Babylon,

there we sat down and wept,

when we remembered Zion.

Seventy years later, their children and grandchildren would make the difficult journey back home. But others remained behind. The Jews in Babylon prospered, and for centuries Babylon was renowned as the center of Jewish learning, where the scriptures of Torah and later the Talmud were written. Furthermore, while in Babylon the Jews absorbed from the Babylonians the idea of universal empire, which influenced Jewish self-understanding ever after as a people called to establish God's universal reign.

History

During the first centuries of the "Old Babylonian" period (that followed the Sumerian revival under Ur-III), kings and people in high position often had Amorite names, and supreme power rested at Isin.

A constant intercourse was maintained between Babylonia and the west—with Babylonian officials and troops passing to Syria and Canaan, while Amorite colonists were established in Babylonia for the purposes of trade. One of these Amorites, Abi-ramu or Abram by name, is the father of a witness to a deed dated in the reign of Hammurabi's grandfather. (His identity with the biblical Abraham is unproven, however.)

The city of Babylon was given hegemony over Mesopotamia by their sixth ruler, Hammurabi (1780 B.C.E.; dates uncertain). He was a very efficient ruler, giving the region stability after turbulent times, and transforming what had been an unstable collection of city-states into an empire that spanned the fertile crescent of Mesopotamia.

A great literary revival followed. One of the most important works of this "First Dynasty of Babylon," as the native historians called it, was the compilation of a code of laws. This was made by order of Hammurabi after the expulsion of the Elamites and the settlement of his kingdom. A copy of the Code of Hammurabi[1] was found by J. de Morgan at Susa, and is now in the Louvre.[2] This code recognized that kingly power derived from God and that earthly rulers had moral duties, as did their subjects. It laid out Hammurabi's task “to bring about the rule of righteousness in the land, to destroy the wicked and the evil-doers” and to fear God.

The armies of Babylonia were well disciplined, and they conquered the city-states of Isin, Elam, and Uruk, and the strong Kingdom of Mari. The rule of Babylon was even obeyed as far as the shores of the Mediterranean. But Mesopotamia had no clear boundaries, making it vulnerable to attack. Trade and culture thrived for 150 years, until the fall of Babylon in 1595 B.C.E.

The last king of the dynasty was Samsu-Ditana, son of Ammisaduqa. He was overthrown following the sack of Babylon in 1595 B.C.E. by the Hittite king Mursili I, and Babylonia was turned over to the Kassites (Kossaeans) from the mountains of Iran, with whom Samsu-Iluna had already come into conflict in his sixth year. Kandis or Gandash of Mari founded the Kassite dynasty. The Kassites renamed Babylon Kar-Duniash, and their rule lasted for 576 years. With this foreign dominion, that offers a striking analogy to the contemporary rule of the Hyksos in Egypt, Babylonia lost its empire over western Asia. Syria and Canaan became independent, and the high-priests of Asshur made themselves kings of Assyria. Most divine attributes ascribed to the Semitic kings of Babylonia disappeared at this time; the title of "god" was never given to a Kassite sovereign. However, Babylon continued to be the capital of the kingdom and the “holy” city of western Asia, where the priests were all-powerful, and the only place where the right to inheritance of the old Babylonian empire could be conferred.

Neo-Babylonian Empire

Through the centuries of Assyrian domination that followed, Babylonia enjoyed a prominent status, or revolting at the slightest indication that it did not. However, the Assyrians always managed to restore Babylonian loyalty, whether through granting of increased privileges, or militarily. That finally changed in 627 B.C.E. with the death of the last strong Assyrian ruler, Ashurbanipal, and Babylonia rebelled under Nabopolassar the Chaldean the following year. With help from the Medes, Niniveh was sacked in 612, and the seat of empire was again transferred to Babylonia.

Nabopolassar was followed by his son Nebuchadnezzar II, whose reign of 43 years made Babylon once more the mistress of the civilized world. Only a small fragment of his annals has been discovered, relating to his invasion of Egypt in 567 B.C.E., and referring to “Phut of the Ionians.” The Bible indicates that during his campaigns in the Levant, Nebuchadnezzar laid waste to Judah and Jerusalem, destroyed the Temple and took its leading citizens into exile. The horrific sufferings experienced by the people under siege by the Babylonians are memorialized in the Book of Lamentations. Yet according to the prophet Jeremiah, the conquest was decreed by God, as judgment for the sins of Judah and her people.

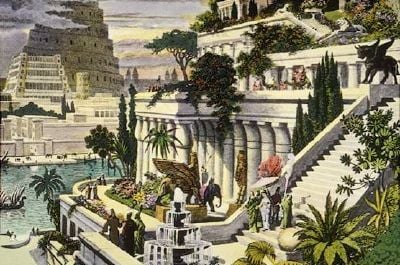

Herodotus describes Babylon at this period as the most splendid in the known world. It was impressive, he said, both for its size and its attractiveness. Its outer walls were 56 miles in length, 80 feet thick and 320 feet high, he said. Nebuchadnezzar built the famous hanging gardens to cheer up his homesick wife, Amytis, daughter of the king of the Medes, a much more fertile and green land than sun-baked Babylonia.

Of the reign of the last Babylonian king, Nabonidus (Nabu-na'id), and the conquest of Babylonia by the Persian king Cyrus, there is a fair amount of information available. It was in the sixth year of Nabonidus (549 B.C.E.) that Cyrus, the Achaemenid Persian king of Anshan in Elam, revolted against his suzerain Astyages, king of the Manda or Medes, at Ecbatana. Astyages' army betrayed him to his enemy, and Cyrus established himself at Ecbatana, thus putting an end to the empire of the Medes. Three years later Cyrus had become king of all of Persia, and was engaged in a campaign in the north of Mesopotamia. Meanwhile, Nabonidus had established a camp in the desert, near the southern frontier of his kingdom, leaving his son Belshazzar (Belsharutsur) in command of the army.

In 538 B.C.E., Cyrus invaded Babylonia. A battle was fought at Opis in the month of June, where the Babylonians were defeated; and immediately afterwards Sippara surrendered to the invader. Nabonidus fled to Babylon, where Gobryas pursued him, and on the sixteenth of Tammuz, two days after the capture of Sippara, "the soldiers of Cyrus entered Babylon without fighting." Nabonidus was dragged from his hiding place, and Kurdish guards were placed at the gates of the great temple of Bel, where the services continued without interruption. Cyrus did not arrive until the third of Marchesvan (October), Gobryas having acted for him in his absence. Gobryas was now made governor of the province of Babylon, and a few days afterwards the son of Nabonidus died. A public mourning followed, lasting six days, and Cambyses accompanied the corpse to the tomb.

Nabonidus had been a patron of the Moon-god Sin, according to an inscription recounting his restoration of the temple of the Moon-god at Harran; for this he had earned the displeasure of the priests of Bel-Marduk at Babylon. He had also alienated the local priesthoods by removing the images of the local gods from their ancestral shrines, to his capital Babylon. Furthermore, the military party despised him on account of his antiquarian tastes. He seems to have left the defense of his kingdom to others, occupying himself with the more congenial work of excavating the foundation records of the temples and determining the dates of their builders. Thus, when Cyrus entered Babylon, he claimed to be the legitimate successor of the ancient Babylonian kings and the avenger of Bel-Marduk, who was wrathful at the impiety of Nabonidus.

Babylon under the Persians

The invasion of Babylonia by Cyrus was doubtless facilitated by the presence of foreign exiles like the Jews, who had been planted in the midst of the country. One of the first acts of Cyrus was to allow these exiles to return to their own homes, carrying with them the images of their gods and their sacred vessels. The permission to do so was embodied in a proclamation, whereby the conqueror endeavored to justify his claim to the Babylonian throne. The Jews were also allowed to rebuild the Temple. The feeling was still strong that none had a right to rule over western Asia until Bel and his priests had consecrated him to the office; and accordingly, Cyrus henceforth assumed the imperial title of “king of Babylon.”

The Jews understood their time in Babylon as one of chastisement but they had also thought deeply about their experiences there and it was during this time that many of the customs and practices that characterize Judaism developed, including the synagogue as a place for prayer and study and many books of the Bible were compiled. The Bible (or the Torah) began to displace the Temple at the center of Jewish life. Jeremiah advised the exiles to "plant vineyards, build houses, marry off their daughters and work and pray for the prosperity and peace of the city in which they dwelt, for its common welfare was their own welfare" (Jeremiah 29:5-7). This enabled Jews of the Babylonian Diaspora to develop an understanding of their role in the world that did not require the Temple priesthood or sacrificial system. Jewish sense of identity and Jewish practice centered on the study of the Torah, instead.

A sizable Jewish presence remained in Babylon even after the destruction of the second temple in 70 C.E. and on into the Islamic period. Babylon became a leading center of Jewish learning; it was there that the Babylonian Talmud (Talmud Bavli), one of the most important texts of Rabbinic Judaism, was collected by Rav Ashi and Ravina in 550 C.E.

A year before Cyrus' death, in 529 B.C.E., he elevated his son Cambyses II in the government, making him king of Babylon, while he reserved for himself the fuller title of “king of the (other) provinces” of the empire. It was only when Darius Hystaspis ("the Magian") acquired the Persian throne and ruled it as a representative of the Zoroastrian religion, that the old tradition was broken and the claim of Babylon to confer legitimacy on the rulers of western Asia ceased to be acknowledged. Darius, in fact, entered Babylon as a conqueror.

After the murder of Darius, it briefly recovered its independence under Nidinta-Bel, who took the name of Nebuchadnezzar III, and reigned from October 521 B.C.E. to August 520 B.C.E., when the Persians took it by storm. A few years later, probably 514 B.C.E., Babylon again revolted under Arakha; on this occasion, after its capture by the Persians, the walls were partly destroyed. E-Saggila, the great temple of Bel, however, still continued to be kept in repair and to be a center of Babylonian patriotism, until at last the foundation of Seleucia diverted the population to the new capital of Babylonia and the ruins of the old city became a quarry for the builders of the new seat of government.

Science and mathematics

Among the sciences, astronomy and astrology occupied a conspicuous place in Babylonian society. Astronomy was of old standing in Babylonia, and the standard work on the subject, written from an astrological point of view, later translated into Greek by Berossus, was believed to date from the age of Sargon of Akkad. The zodiac was a Babylonian invention of great antiquity; and eclipses of the sun and moon could be foretold. Observatories were attached to the temples, and astronomers regularly sent reports to the king. The stars had been numbered and named at an early date, and there remain tables of lunar longitudes and observations of the phases of Venus. Great attention was naturally paid to the calendar, and there is existence of a week of seven days and another of five days in use.

In Seleucid and Parthian times, the astronomical reports were of a thoroughly scientific character; how much earlier their advanced knowledge and methods were developed is uncertain.

The development of astronomy implies considerable progress in mathematics; it is not surprising that the Babylonians should have invented an extremely simple method of ciphering, or have discovered the convenience of the duodecimal system. The ner of 600 and the sar of 3,600 were formed from the unit of 60, corresponding with a degree of the equator. Tablets of squares and cubes, calculated from 1 to 60, have been found at Senkera, and a people acquainted with the sundial, the clepsydra, the lever and the pulley, must have had no mean knowledge of mechanics. A crystal lens, turned on the lathe, was discovered by Austen Henry Layard at Nimrud along with glass vases bearing the name of Sargon; this could explain the excessive minuteness of some of the writing on the Assyrian tablets, and a lens may also have been used in the observation of the heavens.

The Babylonian system of mathematics was sexagesimal, or a base 60 numeral system. From this is derived the modern-day usage of 60 seconds in a minute, 60 minutes in an hour, and 360 degrees in a circle. The Babylonians were able to make great advances in mathematics for two reasons. First, the number 60 has many divisors (2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 10, 12, 15, 20, and 30), making calculations easier. Additionally, unlike the Egyptians and Romans, the Babylonians had a true place-value system, where digits written in the left column represented larger values (much as in the base ten system: 734 = 7×100 + 3×10 + 4×1). Among the Babylonians mathematical accomplishments were the determination of the square root of two correctly to six decimal places.[3] They also demonstrated knowledge of the Pythagorean theorem well before Pythagoras, as evidenced by a tablet translated by Dennis Ramsey and dating to circa 1900 B.C.E.[4]:

4 is the length and 5 is the diagonal.

What is the breadth?

Its size is not known.

4 times 4 is 16. 5 times 5 is 25.

You take 16 from 25 and there remains 9.

What times what shall I take in order to get 9?

3 times 3 is 9. 3 is the breadth.

Location

The city of Babylon, the main city of Babylonia, was found on the Euphrates River, about 110 kilometers (68 miles) south of modern Baghdad, just north of what is now the Iraqi town of Al Hillah.

Notes

- ↑ The Code of Hammurabi Translated by L. W. King The Avalon Project. Retrieved September 23, 2022.

- ↑ Code of Hammurabi Stele Louvre Collections. Retrieved September 23, 2022.

- ↑ Janet L. Beery and Frank J. Swetz, The Best Known Old Babylonian Tablet? Mathematical Association of America (MAA). Retrieved September 23, 2022.

- ↑ Bruce Ratner, Pythagoras: Everyone knows his famous theorem, but not who discovered it 1000 years before him Journal of Targeting, Measurement and Analysis for Marketing 17 (2009): 229–242. Retrieved September 23, 2022.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bryce, Trevor. Babylonia: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2016. ISBN 978-0198726470

- Layard, Austin Henry. Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon. Adamant Media Corporation. 2001. ISBN 978-1402174445

- Parker, Richard A., and Waldo H. Dubberstein. Babylonian Chronology: 626 B.C.E. - A.D. 75. Wipf and Stock, 2007. ISBN 978-1556354533

External links

All links retrieved August 26, 2023.

- Old Babylonian Period The History of the Ancient Near East

- Babylonian Mathematics

- Babylonian Astrology

- Bibliography of Mesopotamian Astronomy and Astrology

- The Religion of Babylonia and Assyria by Theophilus G. Pinches (many deities' names are now read differently, but this detailed 1906 work is a classic).

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.