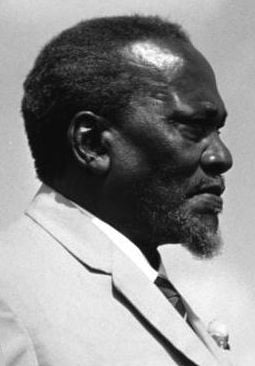

Jomo Kenyatta

Jomo Kenyatta (October 20, 1893 – August 22, 1978) was a Kenyan politician, the first Prime Minister (1963–1964) and President (1964–1978) of an independent Kenya. He is considered the founding father of the Kenyan Nation. Imprisoned under the British, he emerged as leader of the independence struggle. He created a one party system dominated by members of his own tribe. His successor continued in power, ruling autocratically and accumulating a personal fortune, until 2002.

On the one hand, Kenyatta is a symbol of his nation, on the other he left a legacy of corruption and favoritism that did little to place his state on the road to prosperity. His policies were pro-Western and he did much to encourage white Kenyans to remain in the country after independence.

Life

Kenyatta was born Kamau wa Ngengi in the village of Ichaweri, Gatundu, in British East Africa (now Kenya), a member of Kikuyu people. He assisted his medicine man grandfather as a child after his parents' death. He went to school in the Scottish Mission Center at Thogoto and was converted to Christianity in 1914, with the name John Peter, which he later changed to Johnstone Kamau. He moved to Nairobi. During the First World War he lived with Maasai relatives in Narok and worked as a clerk.

In 1920, he married Grace Wahu and worked in the Nairobi City Council water department. His son Peter Muigai was born on November 20. Jomo Kenyatta entered politics in 1924, when he joined the Kikuyu Central Association. In 1928, he worked on Kĩkũyũ land problems before the Hilton Young Commission in Nairobi. In 1928, he began to edit the newspaper Muigwithania (Reconciler).

Kenyatta had two children from his first marriage with Grace Wahu: Son Peter Muigai Kenyatta (born 1920), who later became a deputy minister; and daughter Margaret Kenyatta (born 1928), who served as the first woman mayor of Nairobi between 1970-76. Grace Wahu died in April 2007.[1].

He had one son, Peter Magana Kenyatta (born 1943) from his short marriage with Englishwoman Edna Clarke.[2] He left her to return to Kenya in 1946.

Kenyatta's third wife died when giving childbirth 1950, however, newborn daughter, Jane Wambui, survived.[3]

The most popular of Kenyatta's wives was Ngina Kenyatta (née Muhoho), also known as Mama Ngina. They were married in 1951. It was she who would make public appearances with Kenyatta. They had four children: Christine Warnbui (born 1952), Uhuru Kenyatta (born 1963), Anna Nyokabi (also known as Jeni) and Muhoho Kenyatta (born 1964). Uhuru Kenyatta was elected the fourth president of Kenya in 2013.

Jomo Kenyatta died on August 22, 1978, in Mombasa and was buried on August 31 in Nairobi.

Early Career Overseas

In 1929, the KCA sent Kenyatta to London to lobby for their views on Kikuyu tribal land affairs. He wrote articles to British newspapers about the matter. He returned to Kenya in 1930, in the midst of much debate over female circumcision. In 1931, he went back to London and ended up enrolling in Woodbrooke Quaker College in Birmingham.

In 1932–1933, he briefly studied economics in Moscow at the Comintern school, KUTVU (University of the Toilers of the East) before his sponsor, the Trinidadian Communist George Padmore, fell out with his Soviet hosts, and he was forced to move back to London. In 1934, he enrolled at University College London and from 1935, studied social anthropology under Bronislaw Malinowski at the London School of Economics. During all this time he lobbied on Kikuyu land affairs. He published his revised LSE thesis as Facing Mount Kenya in 1938, under his new name Jomo Kenyatta. During this period he also was an active member of a group of African, Caribbean, and American intellectuals that included at various times C.L.R. James, Eric Williams, W.A. Wallace Johnson, Paul Robeson, and Ralph Bunche. He also was an extra in the film, Sanders of the River (1934), directed by Alexander Korda and starring Paul Robeson.

During World War II, he labored at a British farm in Sussex to avoid conscription into the British army, and also lectured on Africa for the Workman's Education Association.

Return to Kenya

In 1946, Kenyatta founded the Pan-African Federation with Kwame Nkrumah. In the same year, he returned to Kenya and was married for the third time, to Grace Wanjiku. He became a principal of Kenya Teachers College. In 1947, he became a president of the Kenya African Union (KAU). He began to receive death threats from white settlers after his election.

His reputation with the British government was marred by his assumed involvement with the Mau Mau Rebellion. He was arrested in October 1952, and indicted on the charges of organizing the Mau Mau. The trial dragged on for months. The defense argued that the white settlers were trying to scapegoat Kenyatta and that there was no evidence tying him to the Mau Mau. Louis Leakey was brought in as translator and was accused of mistranslating because of prejudice, which seemed absurd to Louis. On the basis of a few prejudicial statements in his writings, Kenyatta was convicted on April 8, 1953, was sentenced to seven years at hard labor, and was exiled from Kenya. Contemporary opinion linked him with the Mau Mau but later research argues otherwise. Kenyatta was in prison until 1959. He was then sent into exile on probation in Lodwar, a remote part of Kenya.

Leadership

The state of emergency was lifted in December 1960. In 1961, both successors of the former KAU party, the Kenya African National Union (KANU) and the Kenya African Democratic Union (KADU) demanded his release. On May 14, 1960, Kenyatta was elected KANU president in absentia. He was fully released on August 21, 1961. He was admitted into the Legislative Council the next year when one member handed over his seat, and contributed to the creation of a new constitution. His initial attempt to reunify KAU failed.

In elections in May 1963, Kenyatta's KANU won 83 seats out of 124. On June 1, Kenyatta became prime minister of the autonomous Kenyan government, and was known as mzee (a Swahili word meaning "old man" or "elder"). At this stage, he asked white settlers not to leave Kenya and supported reconciliation. He retained the role of prime minister after independence was declared on December 12, 1963. On December 12, 1964, Kenya became a republic, with Kenyatta as executive president.

Kenyatta's policy was on the side of continuity, and he kept many colonial civil servants in their old jobs. He asked for British troops' help against Somali rebels (Shiftas) in the northeast and an army mutiny in Nairobi (January 1964), a subsequent mutiny in 1971, was nipped in the bud with the then Attorney General (Kitili Mwenda) and Army commander (Major Ndolo) forced to resign. Some British troops remained in the country. On November 10, 1964, KADU's representatives joined the ranks of KANU, forming a single party.

Kenyatta instituted a relatively peaceful land reform; on the bad side, his land policies deeply entrenched corruption within Kenya with choice parcels of land given to his relatives and friends (the so-called "Kiambu Mafia"), and Kenyatta becoming the nation's largest landowner. He also favored his tribe, the Kikuyu, to the detriment of all the others.

To his credit, he oversaw Kenya's joining of the United Nations, and concluded trade agreements with Milton Obote's Uganda and Julius Nyerere's Tanzania. He pursued a pro-Western, anti-Communist foreign policy.[4] Stability attracted foreign investment and he was an influential figure everywhere in Africa. However, his authoritarian policies drew criticism and caused dissent.

Kenyatta was re-elected in 1966, and the next year changed the constitution to gain extended powers. This term brought border conflicts with Somalia and more political opposition. He made the Kĩkũyũ-led KANU practically the only political party of Kenya. His security forces harassed dissidents and are suspected to be linked to several murders of opposition figures, such as Pio Gama Pinto, Tom Mboya, and J.M. Kariuki. Some have also tried to link him to the deaths of C.M.G. Argwings-Kodhek and Ronald Ngala, but this needs clarification as they both died in car accidents. He was re-elected again in 1974, in elections that were neither free nor fair, in which he ran alone.

Kenyatta was a controversial figure. He is accused by his critics of having left the Kenyan republic at risk from tribal rivalries, given that his dominant Kĩkũyũ tribesmen did not like the idea of having a president from a different tribe. He was succeeded by Daniel arap Moi.

Nairobi's Jomo Kenyatta International Airport is named after him. Kenyatta never spent a night in Nairobi. Instead, he was always driven to his village home in Gatundu.

Quotes

"I have no intention of retaliating or looking backwards. We are going to forget the past and look forward to the future" (1964).[5]

"The basis of any independent government is a national language, and we can no longer continue aping our former colonizers … those who feel they cannot do without English can as well pack up and go" (1974).[6]

"Some people try deliberately to exploit the colonial hangover for their own purpose, to serve an external force. To us, Communism is as bad as imperialism" (1964).[7]

"Don't be fooled into turning to Communism looking for food."[8]

Books by Jomo Kenyatta

- Facing Mount Kenya: The Tribal Life of the Gikuyu. New York: Vintage Books, 1976. ISBN 978-0404146764

- My people of Kikuyu and the life of Chief Wangombe. London: Oxford University Press, 1971. ASIN B004V7BQ3I

- Suffering Without Bitterness: The Founding of the Kenya Nation. Nairobi: East African Publishing House, 1973.ASIN B003VMYH1C

- Kenya: The land of conflict. Manchester: Panaf Service, 1971. ASIN B0007BYMBU

- The challenge of Uhuru;: The progress of Kenya, 1968 to 1970 Nairobi: East African Publishing House, 1971. ASIN B0006C8RQG

Notes

- ↑ Samuel Otienu and Muiruri Maina, Wahu Kenyatta mourned. Retrieved May 6, 2007

- ↑ Mburu Mwangi, Police stop VP's bid for Kenyatta papers. Retrieved May 6, 2007

- ↑ John Kamau, Dear Daddy: Letters straight from the heart. Retrieved May 6, 2007

- ↑ David Lamb, The Africans (New York: Random House, 1982). ISBN 9780394518879

- ↑ Virginia Morell, Ancestral Passions: The Leakey Family and the Quest for Humankind's Beginnings (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995). ISBN 9780684801926

- ↑ David Crystal, English as a Global Language (Cambridge University Press, 2003, ISBN 978-0521530323), 124.

- ↑ Martin Meredith, The Fate of Africa (PublicAffairs, 2011, ISBN 978-1610390712), 266.

- ↑ David Lamb, 61.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Aseka, Eric Masinde. Mzee Jomo Kenyatta. Makers of Kenya's History. Kenya: East African Educational Publishers, 2001. ISBN 9789966251107

- Crystal, David. English as a Global Language. Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0521530323

- Hatch, John Charles. Two African Statesmen: Kaunda of Zambia and Nyerere of Tanzania. Chicago: Regnery, 1976. ISBN 9780809284054

- Lamb, David. The Africans. New York: Random House, 1982. ISBN 9780394518879

- Meredith, Martin. The Fate of Africa. PublicAffairs, 2011. ISBN 978-1610390712

- Morell, Virginia. Ancestral Passions: The Leakey Family and the Quest for Humankind's Beginnings. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995. ISBN 9780684801926

- Murray-Brown, Jeremy. Kenyatta. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1973. ISBN 9780525138556

- Watson, Barrington and Dudley Johnson. The Pan-Africanists. Kingston: Ian Randle, 2000. ISBN 9789768123923

- Wepman, Dennis. Jomo Kenyatta. World Leaders Past & Present. New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1985. ISBN 9780877545750

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.