David and Jonathan were heroic figures of the Kingdom of Israel, whose relationship was recorded the Old Testament books of Samuel. Jonathan, the eldest son of King Saul, was a military commander in his own right who won important battles against the Philistines. After David emerged on the scene as a mere boy who slew the Philistine champion Goliath, Jonathan befriended David. Jonathan later protected David against Saul's fits of murderous jealousy, saving his life on several occasions.

David composed a psalm in honor of Saul and Jonathan after their deaths, in which he praised Jonathan's love as "surpassing that of women." There is, thus, debate among religious scholars as to whether this relationship was platonic or sexual. Some also suggest that the supposed accord between David and Jonathan was a literary device created by the biblical writers to strengthen the fragile unity between the northern tribes who had followed Saul and the tribe of Judah, which followed David and his lineage.

Although David fought a civil war against Saul's son Ish-bosheth, he spared Jonathan's son Mephi-bosheth, keeping him under house arrest in Jerusalem.

Jonathan, son of Saul

Jonathan was already a seasoned military leader when David was still a boy. During Saul's campaign to consolidate his kingdom, he placed Jonathan in charge of 2,000 men at Gibeah while Saul led another 3,000 around Bethel. Jonathan's group led in attacking a Philistine encampment. Saul then mustered the Israelite tribesmen nationwide at Gilgal to deal with the expected Philistine counterstrike. With superior forces, including some 3,000 chariots against the still relatively primitive Israelite army, the Philistines forced the Hebrews on the defensive, and many troops began to desert.

It was here, at Gilgal, that Saul made the fatal mistake of offering sacrifice to God before the arrival of the prophet Samuel, prompting Samuel to declare that God had withdrawn his support of Saul as king. Only 600 men remained with Saul at the time. Saul and Jonathan, meanwhile prepared to meet the Philistines at Micmash. (1 Sam 3)

Through a daring tactic, Jonathan and his armor-bearer alone then killed 20 Philistines, throwing the enemy army into disarray. Moreover, Jonathan's victory caused Hebrew mercenaries who had earlier joined the Philistines to change sides and fight for their fellow Israelites. In addition, the Hebrew soldiers who had deserted at Gilgal now rallied to Saul's and Jonathan's cause. The Philistines were consequently driven back past Beth Aven (1 Sam. 4).

However, during this time, Jonathan was out of communication with his father. He was thus unaware when Saul commanded a sacred fast for the army, with a penalty of death for any who did not observe it. When Jonathan inadvertently violated the fast by eating some wild honey, only the threat of mutiny by troops loyal to him prevented Saul from carrying out the death sentence on his son.

Although Saul left off from pursuing the Philistines after this, heâand presumably Jonathan with himâfought ceaselessly against the Israelites' enemies on all sides, including the nations of Moab, Ammon, Edom, the Amalekites, and later battles against the Philistines.

Story of David and Jonathan

It was at one of these battles against the Philistines that David first appeared on the scene. A handsome, ruddy-cheeked youth and the youngest son of Jesse, David was brought before Saul after having slain the giant Philistine champion Goliath with only a stone and sling (1 Sam. 17:57).

Jonathan was immediately struck with David on their first meeting: "When David had finished speaking to Saul, Jonathan became one in spirit with David, and he loved him as himself" (1 Sam. 18:1). That same day, Jonathan made an unspecified "covenant" with David, removing the rich garments he wore and offering them to his new young friend, including even his sword and his bow (1 Sam. 18:4). David returned from this battle to songs of praise that gave him more credit than Saul for the victory. "Saul has killed his thousands," from the popular song, "and David his tens of thousands." This drew the violent jealousy of Saul, prompted by an "evil spirit from the Lord." On two occasions while Saul prophesied to the music of David's harp, Saul hurled his spear at David, but David eluded the attacks (1 Sam. 18:5-11).

As David grew into manhood, his reputation as a military commander grew even stronger. Saul now saw David as a serious threat and attempted several more times to do away with him. Promising David the hand of his royal daughter Michal in marriage, Saul required 100 enemy foreskins in lieu of a dowry, hoping David would be killed trying to obtain them (1 Sam. 18:24-25). David, however, returned with a trophy of double the number, and Saul had to fulfill his end of the bargain.

Later, Saul ordered Jonathan to assassinate David, but Jonathan instead warned David to be on his guard. Jonathan then succeeded in dissuading the king from his plans, saying:

Let not the king do wrong to his servant David; he has not wronged you, and what he has done has benefited you greatly. He took his life in his hands when he killed the Philistine. The Lord won a great victory for all Israel, and you saw it and were glad. Why then would you do wrong to an innocent man like David by killing him for no reason (1 Sam 9:4-6).

Brought to his senses by Jonathan's words, Saul swore an oath not to do further harm to David: "As surely as the Lord lives," he said, "David will not be put to death." The biblical writers, however, portray Saul as doomed to carry out his tragic fate, and the "evil spirit from the Lord" continued to harass him.

Saul thus continued to devise a way to do away with David, but this time it would be Michal who foiled her father's plans by warning David to escape through their bedroom window. After fleeing to Ramah, David consulted with Jonathan, who assured him that Saul had no further plans to kill him. David insisted, however, declaring that Saul was now keeping his plans secret because of Jonathan's closeness to David. The two men reaffirmed their covenant of love for each other, and Jonathan pledged to discover Saul's true plans with regard to David (1 Sam. 20:16-17).

Jonathan approached his father at a ceremonial dinner to plead David's cause. However Saul flared up in anger at Jonathan saying: "You son of a perverse and rebellious woman! Don't I know that you have sided with the son of Jesse to your own shame and to the shame of the mother who bore you? As long as the son of Jesse lives on this earth, neither you nor your kingdom will be established. Now send and bring him to me, for he must die!" This time, when Jonathan attempted to dissuade Saul from his rash course, the king hurled his spear at his son. Jonathan was so grieved that he did not eat for days (1 Sam. 20:30-34).

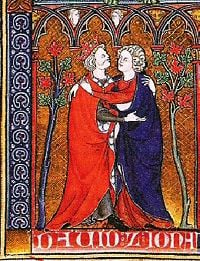

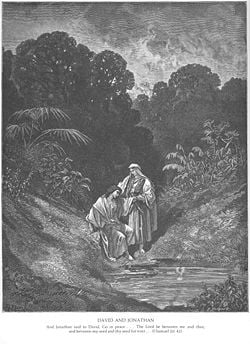

He then went to David at his hiding place to tell him that he must leave. "David rose from beside the stone heap and prostrated himself with his face to the ground. He bowed three times, and they kissed each other, and wept with each other; David wept the more. Then Jonathan said to David, 'Go in peace, since both of us have sworn in the name of the LORD, saying, "The LORD shall be between me and you, and between my descendants and your descendants, forever'" (1Sam. 20:41-42).

David then became an outlaw and a fugitive, gathering a band of several hundred men loyal to him. Saul, still seeing him as a threat to the throne, continued to pursue David. Jonathan, however, again reiterated his covenant with David and even pledged to honor David as king, saying: "My father Saul will not lay a hand on you. You will be king over Israel, and I will be second to you. Even my father Saul knows this" (1 Sam. 23:15-18).

With no safe haven in Israelite territory, David eventually ended up working as a mercenary captain for the Philistine king Achish. Later, when Jonathan and Saul were slain on Mount Gilboa by the Philistines, however, David was not involved (1 Sam. 31:2). Hearing of their deaths, David composed a psalm of lamentation commemorating both of the fallen leaders:

- Saul and Jonathanâin life they were loved and gracious, and in death they were not parted.

- They were swifter than eagles, they were stronger than lions.

- O daughters of Israel, weep for Saul, who clothed you in scarlet and finery,

- who adorned your garments with ornaments of gold...

- I am distressed for you, my brother Jonathan;

- greatly beloved were you to me;

- your love to me was wonderful, passing the love of women" (2 Sam. 1:23-26).

With Jonathan dead, Saul's younger son Ish-bosheth succeeded him as king of Israel, while David reigned over the tribe of Judah at Hebron. A civil war of several years followed, which ended after Saul's military commander Abner went over to David's side and Ish-bosheth was soon assassinated, leaving David the unchallenged ruler of both Israel and Judah until the rebellion of his son Absalom.

Interpretation of their relationship

Platonic

The traditional view is that Jonathan and David loved one another as brothers. Jonathan's "loving him as himself" refers simply to unselfish love, a commandment found in both the Old and the New Testaments: "Love your neighbor as yourself." The Book of Samuel indeed documents real affection and physical intimacy (hugging and kissing) between Jonathan and David, but this does not indicate a sexual component to their love. Even in modern times, kissing is a common social custom between men in the Middle East for greetings or farewells.

In rabbinical tradition, Jonathan's love for David is considered the archetype of disinterestedness (Ab. v. 17). Jonathan is ranked by Rabbi Judah the Saint among the great self-denying characters of Jewish history. However, an alternative rabbinical opinion held that his love for David was a result of his conviction that David's great popularity was certain to place David on the throne in the end (B. M. 85a). One tradition holds that Jonathan actually did not go far enough to support David, arguing that Jonathan shared in Saul's guilt for the slaughter of the priests of Nob (I Sam. 22: 18-19), which he could have prevented by providing David two loaves of bread (Sanh. 104a).

Jonathan's giving his royal clothes and arms to David at their first meeting is simply a recognition that David deserved them, since Jonathan himself had not dared to face the Philistine champion Goliath, as David did. Moreover, by agreeing that David would be king and Jonathan his second-in-command, Jonathan can be seen to be insuring his own survival after Saul's death. In fact, their covenant stipulated that David should not exterminate Jonathan's posterity: "The Lord is witness between you and me, and between your descendants and my descendants forever" (1 Sam. 20:42).

Literary critic Harold Bloom has argued that the biblical writers consciously created a pattern in which the elder "brother" of heir came to serve the younger, as part of a historiography justifying the kingship of Solomon over his elder brother Adonijah.[1] David and Jonathan may thus be seen as an example of this pattern, in which the potential antagonistsâunlike Cain and Abel or Esau and Jacobânever came to experience animosity.

Romantic and erotic

Some modern scholars, however, interpret the love between David and Jonathan as more intimate than mere friendship. This interpretation views the bonds the men shared as romantic love, regardless of whether it was physically consummated.[2] Each time they reaffirm their covenant, love is the only justification provided. Although both Jonathan and David were married to their own wives and Jonathan had sired at least one son, David explicitly stated, on hearing of Jonathan's death, that for him, Jonathan's love exceeded "that of women."

Some commentators go further than to suggest a merely romantic relationship between Jonathan and David, arguing that it was a full fledged homosexual affair. For example, the anonymous Life of Edward II, c. 1326 C.E., has: "Indeed I do remember to have heard that one man so loved another. Jonathan cherished David, Achilles loved Patroclus." In Renaissance art, the figure of David is thought by some to have taken on a particular homo-erotic charge, as some see in the colossal statue of David by Michelangelo and in Donatello's David.

Oscar Wilde, at his 1895 sodomy trial, used the example of David and Jonathan as "the love that dare not speak its name." More recently, the Anglican bishop of Liverpool, James Jones, drew attention to the relationship between David and Jonathan by describing their friendship as: "Emotional, spiritual and even physical." He concluded by affirming: "(Here) is the Bible bearing witness to love between two people of the same gender."[3]

Critical view

Biblical scholarship has long recognized a concern in the narrative of the Books of Samuel to present David as the sole legitimate claimant to the throne of Israel. The story of Jonathan's unity with Davidâincluding his willingness to accept David rather than himself as kingâis thus seen as a literary device showing that Saul's heir-apparent recognized God's supposed plan to place David's line on the throne instead of Saul's. The story evolved in the context of the need to strengthen the fragile unity of the northern and southern tribes, which fractured several times during David's reign and was destroyed permanently in the time of his grandson Rehoboam. A similar motive is seen in what critics see as the "fiction" of David sparing Saul's life several times and his supposed outrage that anyone would dare to harm the "Lord's anointed."

The story of Jonathan ceding his kingship to David, of course, could not be challenged, since Jonathan was killed at Gilboa, by the very Philistine enemy with whom David was then allied. In fact, the house of David continued to war against the house of Saul for several years, and several northern rebellions followed, even after the death of Jonathan's brother Ish-bosheth.

While this does not rule out the possibility of romantic or homosexual love between the David and Jonathan, this scenarioâlike the story of their supposed political unionâis better seen as a product of contemporary ideological agendas than historical reality.

Notes

- â Bloom, 1990.

- â David M. Halperin, 1990, p. 83.

- â liverpool.anglican.org, Lambeth essay. Retrieved June 10, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ackerman, Susan. When Heroes Love: The Ambiguity of Eros in the Stories of Gilgamesh and David. New York: Columbia University Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0231132619

- Bloom, Harold, and David Rosenberg. The Book of J. New York: Grove Weidenfeld, 1990. ISBN 978-0802110503

- Gordon, Andrew. Politics and Love: Reading and Re-Reading the Jonathan and David Story. Thesis (Rab.)âHebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, Brookdale Center, 2008.

- Halperin, David M. One Hundred Years of Homosexuality. New York: Routledge, 1990.

- Hubble, Christopher Amos. Lord Given Lovers: The Holy Union of David & Jonathan. New York: iUniverse, 2003. ISBN 0595298699

- Schecter, Stephen. David and Jonathan: An Epic Poem of Love and Power in Ancient Israel. Robert Davies Multimedia Publishing, 1997. ISBN 1895854660

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.