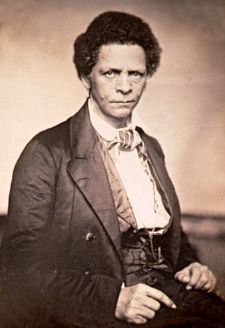

Joseph Jenkins Roberts

7th President of Liberia (1872) | |

| Term of office | January 3, 1848 – January 7, 1856 January 1, 1872-January 3, 1876 |

| Preceded by | None (1848) James Skivring Smith (1872) |

| Succeeded by | Stephen Allen Benson (1848) James Spriggs Payne (1872) |

| Date of birth | March 15, 1809 |

| Place of birth | Norfolk, Virginia |

| Date of death | February 24, 1876 (aged 66) |

| Place of death | Monrovia, Liberia |

| Spouse | (1) Sarah Roberts (2) Jane Rose Waring Roberts |

| Political party | Republican Party |

Joseph Jenkins Roberts (March 15, 1809 – February 24, 1876) was the first (1848–1856) and seventh (1872–1876) president of Liberia after helping lead the country to independence as its first nonwhite Governor. Roberts was born in Norfolk, Virginia and emigrated to Liberia in 1829 in an attempt to take part in the movement initiated by the African Colonization Society. He also is believed to have wished to help spread his Christian ideals to those indigenous peoples that he set out to encounter on the African continent. He opened a trading store in Monrovia, and later engaged in politics. When Liberia became independent in 1847 he became the first president and served until 1856. In 1872, he would serve again as Liberia's seventh president. Liberia, which means "Land of the Free," was founded as an independent nation for free-born and formerly enslaved African Americans.

During his tenure as president, Roberts pushed for European and United States recognition and met with several world leaders to see to the realization of such. His diplomatic skills proved to be of a high order, as they helped him to deal aptly with the indigenous peoples he encountered once in Africa, as well as the leaders whom he met with in his attempt to form a viable and independent Liberian nation. Bridging European and African ideals was a goal on which Roberts placed great importance. As a native Virginian at the helm of a novel African nation, he was instrumental in making a noble push towards a more united global human community.

Early life

Roberts was born in Norfolk, Virginia as the eldest of seven children to a couple of mixed ancestry, James and Amelia Roberts.[1] His mother Amelia had gained freedom from slavery and had married his father James Roberts, a free negro. James Roberts owned a boating business on the James River and had, by the time of his death, acquired substantial wealth for an African American of his day.[2] Roberts had only one African great grandparent, and he was of more than one half European ancestry. As the Liberian historian Abayomi Karnga noted in 1926, "he was not really black; he was an octoroon and could have easily passed for a white man."[3] As a boy he began to work in his family business on a flatboat that transported goods from Petersburg to Norfolk on the James River.[4] After the death of his father his family moved to Petersburg, Virginia. He continued to work in his family's business, but also served as an apprentice in a barber shop. The owner of the barber shop, William Colson was also a minister of the gospel and one of Virginia's best educated black residents. He gave Roberts access to his private library, which was a source of much of his early education.[2]

Emigrating to Liberia

After hearing of the plans of the American Colonization Society to colonize the African coast at Cape Mesurado near today's Monrovia the Roberts family decided to join an expedition. The reasons for this decision are unknown, but undoubtedly the restrictions of the Black Code in Virginia played an important part. Another probable reason for the decision to emigrate were the religious beliefs of the Roberts family and the desire to spread Christianity and civilization among the indigenous people of Africa.[2] On February 9, 1829, they set off for Africa on the Harriet. On the same ship was James Spriggs Payne, who would later become Liberia's fourth president.[1]

In Monrovia the family established a business with the help of William Colson in Petersburg. The company exported palm products, camwood, and ivory to the United States and traded imported American goods at the company store in Monrovia. In 1835 Colson would also emigrate to Liberia, but would shortly die after his arrival. The business quickly expanded into coastal trade and the Roberts family became a successful member of the local establishment.[2] During this time his brother John Wright Roberts entered the ministry of the Liberia Methodist Church and later became a bishop. The youngest son of the family, Henry Roberts studied medicine at the Berkshire Medical School in Massachusetts and went back to Liberia to work as a physician.[5]

In 1833, Roberts became high sheriff of the colony. One of his responsibilities was the organization of expeditions of the settler militia to the interior to collect taxes from the indigenous peoples and to put down rebellions. In 1839, he was appointed vice governor by the American Colonization Society. Two years later, after the death of governor Thomas Buchanan he was appointed as the first nonwhite governor of Liberia. In 1846 Roberts asked the legislature to declare the independence of Liberia, but also to maintain the cooperation with the American Colonization Society. A referendum was called which was in favor of independence. On July 26, 1847, he declared Liberia independent. He won the first election on October 5, 1847, and was sworn into office as Liberia's first president on January 3, 1848.[1]

First presidency (1847-1856)

After Liberia declared its independence in 1847, Joseph J. Roberts, a freeborn Black who was born in Virginia, was elected Liberia's first president, and Stephen Benson was elected vice-president. Roberts was re-elected three more times to serve a total of eight years, until he lost the election in 1855 to his vice president Stephen Allen Benson.[1]

Attempts to found a state based upon some 3000 settlers proved difficult. Some coastal tribes became Protestants and learned English, but most of the indigenous Africans retained their traditional religion and language. The slave trade continued illicitly from Liberian ports, but this was ended by the British Navy in the 1850s.

The constitution of the new state was modeled on that of the United States, and was democratic in theory although not always in substance.

Foreign relations

Roberts spent the first year of his presidency attempting to attain recognition from European countries and the United States. In 1848 he traveled to Europe to meet Queen Victoria and other heads of state. Great Britain was the first country to recognize Liberia, followed by France in 1848 or 1852 (accounts differ). In 1849, the German cities of Hamburg, Bremen and Lübeck recognized the new nation, as well as Portugal, Brazil, the Kingdom of Sardinia and the Austrian Empire. Norway and Sweden did so in either 1849 or 1863, Haiti in either 1849 or 1864, Denmark in either 1849 or 1869 (accounts differ). However, the United States withheld recognition until 1862, during the presidency of Abraham Lincoln, because the U.S. leaders believed that the southern states would not accept a black ambassador in Washington, D.C.

Relations with indigenous groups; expansion

Resistance from indigenous groups continued, and occasional port calls by American naval vessels provided, in the words of Duignan and Gann, a "definite object lesson to restive locals." One example was the visit of the USS John Adams in 1852, which had a noticeably quieting effect upon the chiefs at Grand Bassa, the coastal region to Monrovia's south.

Maryland Colony declared in 1854 its independence from the Maryland State Colonization Society but did not become part of the Republic of Liberia. It held the land along the coast between the Grand Cess and San Pedro Rivers. In 1856, the independent state of Maryland (Africa) requested military aid from Liberia in a war with the Grebo and Kru peoples who were resisting the Maryland settlers' efforts to control their trade. President Roberts assisted the Marylanders, and a joint military campaign by both groups of African American colonists resulted in victory. In 1857, the Republic of Maryland would join Liberia as Maryland County.

During his presidency Roberts expanded the borders of Liberia along the coast and made first attempts to integrate the indigenous people of the hinterland of Monrovia into the Republic. By 1860, through treaties and purchases with local African leaders, Liberia would have extended its boundaries to include a 600 mile (1000 km) coastline.

Economy, nation building

The settlers built schools and Liberia College (which later became the University of Liberia). During these early years, agriculture, shipbuilding, and trade flourished.

Assessment

Roberts has been described as a talented leader with diplomatic skills. His leadership was instrumental in giving Liberia independence and sovereignty. Later in his career his diplomatic skills helped him to deal effectively with the indigenous people and to maneuver in the complex field of international law and relations.[2]

Between presidencies

After his first presidency Roberts served for fifteen years as a major general in the Liberian army as well as a diplomatic representative in France and Great Britain. In 1862, he helped to found and became the first president of Liberia College in Monrovia, remaining as president until 1876.[6] Roberts frequently traveled to the United States to raise funds for the college. Until his death he held a professorship in jurisprudence and international law.[4]

Second presidency (1872-1876)

In 1871, president Edward James Roye was deposed by elements loyal to the Republican Party on the grounds that he was planning to cancel the upcoming elections. Roberts, one of the Republican Party's leaders, won the ensuing presidential election and thus returned to office in 1872. He served for two terms until 1876. During the incapacitation of Roberts from 1875 until early 1876, Vice-President Gardiner was acting president.

The decades after 1868, escalating economic difficulties weakened the state's dominance over the coastal indigenous population. Conditions worsened, the cost of imports was far greater than the income generated by exports of coffee, rice, palm oil, sugarcane, and timber. Liberia tried desperately to modernize its largely agricultural economy.

Inheritance and legacy

Roberts died on February 24, 1876, less than two months after his second term had ended. In his testament he left $10,000 and his estate to the educational system of Liberia.[1]

Liberia's main airport, Roberts International Airport, the town of Robertsport and Roberts Street in Monrovia are named in honor of Roberts. His face is also depicted on the Liberian ten dollar bill introduced in 1997 and the old five dollar bill in circulation between 1989 and 1991. His birthday, March 15, was a national holiday in Liberia until 1980.[4]

Roberts is noted for his role at the head of Liberia, both before and after full independence was won. His work to move the country towards achieving foreign recognition is marked by his skillful diplomatic efforts. Also noteworthy are his dealings with the indigenous population of the new nation. Bridging European and African ideals was a goal on which Roberts placed great importance. As a native Virginian at the helm of a novel African nation, he was instrumental in making a noble push towards a more united global human community.

| Preceded by: (none) |

President of Liberia 1847–1856 |

Succeeded by: Stephen Allen Benson |

| Preceded by: James Skivring Smith |

President of Liberia 1872–1876 |

Succeeded by: James Spriggs Payne |

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Davis, Stanley A. 1953. This is Liberia. New York, NY: William-Frederick Press.

- Evans-Brown, Judith. 1968. Virginia's other presidents. The Virginian-Pilot.

- Karnga, Abayomi Wilfrid. 1926. History of Liberia. Liverpool, UK: D.H. Tyte.

- Livingston, Thomas W. 1976. The Exportation of American Higher Education to West Africa: Liberia College, 1850-1900. The Journal of Negro Education 45 (3): 246-262.

- Matthews, Pat. 1973. The father of Liberia. Virginia Cavalcade. Autumn:5-11.

- Pham, John-Peter. 2004. Liberia—Portrait of a Failed State. New York, NY: Reed Press. ISBN 1594290121.

- Tazewell, Calvert Walke. 1992. Virginia's ninth president—An anthology on President Joseph Jenkins Roberts (1809-1876). Virginia Beach, VA: W.S. Dawson Co. ISBN 1878515233.

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Roberts, Joseph Jenkins |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Roberts, Joseph J. |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | President of Liberia |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 15, 1809 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Norfolk, Virginia |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 24, 1876 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Monrovia, Liberia |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.