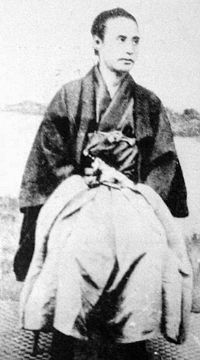

Katsu Kaishu

| Katsu Kaishƫ | |

|---|---|

| 1823-1899 | |

Katsu Kaishƫ | |

| Nickname | Awa Katsƫ |

| Place of birth | Edo, Japan |

| Place of death | Japan |

| Allegiance | Imperial Japan |

| Years of service | 1855-1868 (Tokugawa); 1872-1899 (Imperial Japan) |

| Rank | Naval officer |

| Commands held | Kanrin-maru (warship) Kobe naval school Vice Minister Navy Minister |

| Battles/wars | Boshin War |

| Other work | military theorist |

Katsu KaishĆ« (ć æ”·è Awa Katsu; KaishĆ«; Rintaro; Yoshikuni 1823-1899) was a Japanese naval officer and statesman during the Late Tokugawa shogunate and the Meiji period. An inquisitive student of foreign culture, Kaishu made a study of foreign military technology. When Commodore Matthew Perry of the United States Navy led a squadron of warships into Edo Bay, forcing an end to Japanese isolation, the Japanese shogunate called for solutions to the threat of foreign domination. Katsu submitted several proposals for the creation of a new Japanese navy, including the recruitment of officers according to ability instead of social status, the manufacture of warships and Western-style cannons and rifles, and the establishment of military academies. All of his proposals were adopted and within a few years Katsu himself was commissioned an officer (Gunkan-bugyo) in the shogunal navy.

In 1860, Katsu commanded the Kanrin-maru, a tiny triple-masted schooner, and escorted the first Japanese delegation to San Francisco, California en route to Washington, DC, for the formal ratification of the Harris Treaty. He remained in San Francisco for nearly two months, making close observations of the differences between Japanese and American government and society. In 1866, Navy Commissioner Katsu Kaishu successfully negotiated a peace treaty with the Choshu revolutionaries, ensuring a relatively peaceful and orderly transition of power in the Meiji Restoration. When the Tokugawa shogun abdicated and civil war broke out between his supporters and the new imperial forces, Kaishu negotiated the peaceful surrender of Edo Castle to Saigo Takamori and the Satcho Alliance, and saved not only the lives and property of Edo's one million inhabitants, but the future of the entire Japanese nation. In addition to his military activities, Katsu was a historian and a prolific writer on military and political issues. He is remembered as one of the most enlightened men of his time, able to evaluate Japanâs position in the world and to foresee the political necessity of modernization.

Life

Early Life

Katsu RintarĆ was born in January 1823, in Edo (present day Tokyo) to a low-ranking retainer of the Tokugawa Shogun. His father, Katsu Kokichi, was the head of a minor samurai family, because of bad behavior, was forced to abdicate the headship of his family to his son RintarĆ (KaishĆ«) when the boy was only 15 years old. KaishĆ« was a nickname which he took from a piece of calligraphy (KaishĆ« Shooku æ”·èæžć±) by Sakuma ShĆzan. Kaishu was self-confident and naturally inquisitive about things which were strange to him. He was 18 when he first saw a map of the world. âI was wonderstruck,â he recalled decades later, adding that at that moment he determined to travel the globe.

Though at first the idea of learning a foreign language seemed preposterous to him, because he had never been exposed to a foreign culture, as a youth Katsu studied the Dutch language and aspects of European military science. When the European powers attempted to open contact with Japan, he was appointed translator by the government, and developed a reputation as an expert in western military technology. The Tokugawa shogunate had enforced a strict policy of isolation since 1635, in order to maintain tight control over some 260 feudal domains. However, in 1818 Great Britain took over much of India, and when the Treaty of Nanking was signed at the end of the first Opium War in 1842, they also acquired Hong Kong. In 1853, Commodore Matthew Perry of the United States Navy led a squadron of heavily armed warships into the bay off the shogun's capital, forcing an end to Japanese isolation and inciting 15 years of turmoil in Japan.

It was evident that Japan must act quickly in order to avoid being colonized by foreign powers. The shogunate conducted a national survey, calling for solutions to the problem. Hundreds of responses poured in, some proposing that the country be opened to foreigners, and others advocating the continuation of isolationism; but no one suggested a means for realizing their proposals. Kaishu, then an unknown samurai, submitted a proposal which was clear and concrete. He pointed out that Perry had been able to enter Edo Bay only because Japan did not have a national navy. He proposed that, in recruiting a new navy, the military government break with tradition and choose men for their ability rather than for their social status. Kaishu advised the shogunate to lift its ban on the construction of warships, to manufacture Western-style cannons and rifles, to reorganize the military according to Western standards, and to establish military academies. He pointed out the technological advances being made in Europe and the United States, and challenged the narrow-minded thinking of traditionalists who opposed modern military reform.

Within a few years, all of Kaishu's proposals had been adopted by the shogunate. In 1855 (the second year of the "Era of Stable Government"), Kaishu himself was recruited into government service, and that September he sailed to Nagasaki, as one of a select group of 37 Tokugawa retainers, to the new Nagasaki Naval Academy (Center), where, together with Nagai Naoyuki, he served as director of training from 1855 to 1860, when he was commissioned an officer in the shogunal navy.

Visit to the United States

In 1860, Katsu was assigned to command the Kanrin-maru, a tiny triple-masted schooner, and (with assistance from US naval officer Lt. John M. Brooke), to escort the first Japanese delegation to San Francisco, California en route to Washington, DC, for the formal ratification of the Harris Treaty. The Kanrin Maru, built by the Dutch, was Japan's first steam-powered warship, and its voyage across the Pacific Ocean was meant to signal that Japan had mastered modern sailing and shipbuilding technology. KaishĆ« remained in San Francisco for nearly two months, observing American society, culture and technology. Kaishu was particularly impressed with the contrast between feudal Japan, where a person was born into one of four social classes, warrior, peasant, artisan, or merchant, and remained in that caste for life; and American society. He observed that, âThere is no distinction between soldier, peasant, artisan or merchant. Any man can be engaged in commerce. Even a high-ranking officer is free to set up business once he resigns or retires.â In Japan, the samurai, who received a stipend from their feudal lord, looked down upon the merchant class, and considered it beneath them to conduct business for monetary profit.

Katsu noted that in America, âUsually people walking through town do not wear swords, regardless of whether they are soldiers, merchants or government officials,â while in Japan it was a samurai's strict obligation to be armed at all times. He also remarked on the relationship between men and women in American society: âA man accompanied by his wife will always hold her hand as he walks.â Kaishu, whose status as a low-level samurai made him an outsider among his countrymen, was pleased with the Americans. âI had not expected the Americans to express such delight at our arrival to San Francisco, nor for all the people of the city, from the government officials on down, to make such great efforts to treat us so well.â

Military Service and Civil War

In 1862, Katsu received an appointment as vice-commissioner of the Tokugawa Navy. In 1863, he established a naval academy in Kobe, with the help of his assistant, Sakamoto Ryoma. The following year Katsu was promoted to the post of navy commissioner, and received the honorary title Awa-no-Kami, Protector of the Province of Awa. Katsu argued before government councils in favor of a unified Japanese naval force, led by professionally trained officers and disregarding traditional hereditary domains. During his command as director of the Kobe Naval School, between 1863 and 1864, the institute became a major center of activity for progressive thinkers and reformers. In October of 1864, Kaishu, who had thus far remained in the favor of the shogun, was suddenly recalled to Edo, dismissed from his post and placed under house arrest for harboring known enemies of the Tokugawa. His naval academy was closed down, and his generous stipend reduced to a bare minimum.

In 1866, the shogun's forces suffered a series of humiliating defeats at the hands of the revolutionary Choshu Army, and Tokugawa Yoshinobu, Head of the House of Tokugawa, who would soon become the fifteenth and last Tokugawa Shogun, was obliged to reinstate Katsu to his former post. Lord Yoshinobu did not like Katsu, a maverick within his government, who had broken age-old tradition and law by sharing his expertise with enemies of the shogunate. Katsu had openly criticized his less talented colleagues at Edo for their inability to accept that the days of Tokugawa rule were numbered; and had braved punishment by advising the previous Shogun Tokugawa Iemochi to abdicate. Katsu was recalled to military service because Yoshinobu and his aides knew that he was the only man in Edo who had gained the respect and trust of the revolutionaries.

In August of 1866, Navy Commissioner Katsu Kaishu was sent to Miyajima Island of the Shrine, in the domain of Hiroshima, to meet representatives of the revolutionary alliance of Choshu. Before departing, he told Lord Yoshinobu, âI'll have things settled with the Choshu men within one month. If I'm not back by then, you can assume that they've cut off my head.â In spite of the grave danger, Kaishu traveled alone, without a single bodyguard. Soon after successfully negotiating a peace with Choshu, ensuring a relatively peaceful and orderly transition of power in the Meiji Restoration, Kaishu resigned his post, due to irreconcilable differences with the Tokugawa government, and returned to his home in Edo.

In October 1867, Shogun Tokugawa Yoshinobu announced his abdication and the restoration of power to the emperor. In January 1868, civil war broke out near Kyoto between diehard oppositionists within the Tokugawa camp, and the forces of the new imperial government who were determined to annihilate the remnants of the Tokugawa, so that it would never rise again. The imperial forces, led by Saigo Takamori of Satsuma, were greatly outnumbered, but they routed the army of the former shogun in just three days. The new governmentâs leaders now demanded that Yoshinobu commit ritual suicide, and set March 15 as the date when 50,000 imperial troops would lay siege to Edo Castle, and subject the entire city to the flames of war.

Katsu desperately wanted to avoid a civil war, which he feared would incite foreign agression. Although sympathetic to the anti-Tokugawa cause, Katsu remained loyal to the Tokugawa bakufu during the Boshin War. He was bound by his duty, as a direct retainer of the Tokugawa, to serve in the best interest of his lord, Tokugawa Yoshinobu. In March 1868, Katsu, son of a petty samurai, was the most powerful man in Edo, with a fleet of 12 formidable warships at his disposal. As head of the Tokugawa army, he was determined to burn Edo Castle rather than relinquish it in battle, and to wage a bloody civil war against Saigo's imperial forces.

When Katsu was informed that the imperial government's attack was imminent, he wrote a letter to Saigo, pointing out that the retainers of the Tokugawa were an inseparable part of the new Japanese nation. Instead of fighting with one another, he said, the new government and the old must cooperate in order to deal with the very real threat of colonization by foreign powers, whose legations in Japan anxiously watched the great revolution which had consumed the Japanese nation for the past 15 years. Saigo responded by offering a set of conditions, including the peaceful surrender of Edo Castle, which must be met if war was to be avoided, the House of Tokugawa allowed to survive, and Yoshinobu's life spared. On March 14, one day before the planned attack, Katsu met with Saigo and accepted his conditions. He negotiated the surrender of Edo castle to SaigĆ Takamori and the Satcho Alliance on May 3, 1868, and became the historical figure who not only saved the lives and property of Edo's one million inhabitants, but the future of the entire Japanese nation. Katsu followed the last Shogun, Tokugawa Yoshinobu, into exile in Shizuoka.

Later Years

Katsu returned briefly to government service as Vice Minister of the Imperial Japanese Navy in 1872, and first Minister of the Navy from 1873 until 1878. He was the most prominent of the former Tokugawa retainers who found employment within the new Meiji government. Although his influence within the Navy was minimal, as the Navy was largely dominated by a core of Satsuma officers, Katsu served in a senior advisory capacity on national policy. During the next two decades, Katsu served on the Privy Council and wrote extensively on naval issues until his death in 1899.

In 1887, he was elevated to the title of hakushaku (count) in the new kazoku peerage system.

Katsu recorded his memoirs in the book Hikawa Seiwa.

Legacy

Sakamoto Ryoma, a key figure in the overthrow of the Tokugawa Shogunate, was a protĂ©gĂ© and one-time assistant of Kaishu, whom he considered "the greatest man in Japan." Kaishu shared his extensive knowledge of the Western world, including American democracy, the Bill of Rights, and the workings of the joint stock corporation, with Ryoma. Like Ryoma, Kaishu was a skillful swordsman who never drew his blade on an adversary, despite numerous attempts on his life. âI've been shot at by an enemy about twenty times in all,â Kaishu once said. âI have one scar on my leg, one on my head, and two on my side.â Kaishuâs fearlessness in the face of death sprang from his reverence for life. âI despise killing, and have never killed a man. I used to keep [my sword] tied so tightly to the scabbard, that I couldnÂčt draw the blade even if I wanted to.â

The American educator E. Warren Clark, an admirer of Kaishu who knew him personally, referred to Kaishu as "the Bismark of Japan," for his role in unifying the Japanese nation during the dangerous aftermath of the fall of the Tokugawa shogunate.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Hane, Mikiso, and Mikiso Hane. 1992. Modern Japan: a historical survey. Boulder: Westview Press. ISBN 0813313678 ISBN 9780813313672 ISBN 9780813313672 ISBN 0813313678 ISBN 0813313686 ISBN 9780813313689 ISBN 9780813313689 ISBN 0813313686

- Itakura, Kiyonobu. 2006. Katsu kaishĆ« to meiji ishin. TĆkyĆ: Kasetsusha. ISBN 4773501979 ISBN 9784773501971 ISBN 9784773501971 ISBN 4773501979

- Jansen, Marius B. 1994. Sakamoto RyĆma and the Meiji restoration. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231101732 ISBN 780231101738 ISBN 9780231101738 ISBN 0231101732

- Katsu, Kokichi. 1988. Musui's story: the autobiography of a Tokugawa samurai. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 0816510350 ISBN 9780816510351 ISBN 9780816510351 ISBN 0816510350

- Tipton, Elise K. 2002. Modern Japan: a social and political history. London: Routledge. ISBN 0415185378 ISBN 9780415185370 ISBN 9780415185370 ISBN 0415185378 ISBN 0415185386 ISBN 9780415185387 ISBN 9780415185387 ISBN 0415185386

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.