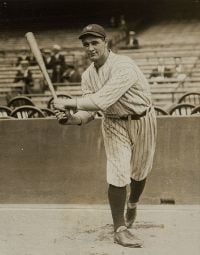

Lou Gehrig

Henry Louis ("Lou") Gehrig (June 19, 1903 – June 2, 1941), born Ludwig Heinrich Gehrig, was an American baseball player, beloved for his dominant offensive play, but even more for his dignity, humility, and good sportsmanship. Playing the majority of his career as a first baseman with the New York Yankees, Gehrig set a number of Major League and American League records over a 15-year career. Gehrig batted right behind the storied Babe Ruth and added to Ruth's prodigious power in one of the most feared lineups in baseball history. While Ruth was known for his excesses and loose living, Gehrig lived a life of probity and was a good-natured foil for Ruth in the popular press.

Gehrig was nicknamed "The Iron Horse" for his durability. Over a 15-year span between 1925 and 1939, he played in 2,130 consecutive games. The streak was broken when Gehrig became disabled with the fatal neuromuscular disease amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), now commonly referred to as Lou Gehrig's Disease. Long believed to be one of baseball's few unbreakable records, the consecutive game streak stood for 56 years until finally broken by Cal Ripken, Jr. in 1995.

Gehrig's farewell speech to Yankee fans and to the nation is remembered as one of the most poignant moments in sports. Knowing that his play had deteriorated and that he had but a short time to live, Gehrig declared himself to be "the luckiest man on the face of the earth" for his career in baseball, the support of the fans, and the courage and sacrifice of his wife and parents.

Gehrig was elected into the Baseball Hall of Fame the year of his retirement, with a waiver of the mandatory five-year waiting period; his number 4 uniform was the first to be retired in baseball history; and his popularity endures to this day. Gehrig was the leading vote getter on the Major League Baseball All-Century Team, chosen in 1999.

Early Life

Lou Gehrig was born in the Yorkville section of Manhattan, the son of poor German immigrants Heinrich Gehrig and Christina Fack. Lou was the only one of four children born to Heinrich and Christina to survive infancy. His father was frequently unemployed due to epilepsy, so his mother was the breadwinner and disciplinarian. Both parents considered baseball to be a schoolyard game; his domineering mother steered young Gehrig toward a career in architecture because an uncle in Germany was a financially successful architect.[1]

Gehrig first garnered national attention for his baseball talents while playing in a game at Cubs Park (now Wrigley Field) on June 26, 1920. Gehrig's New York School of Commerce team was playing a team from Chicago's Lane Tech High School. With his team winning 8–6 in the eighth inning, Gehrig hit a grand slam completely out of the Major League ballpark, an unheard-of feat for a 17-year-old high school boy.[2]

In 1921, Gehrig began attending Columbia University on a football scholarship and pursuing a degree in engineering. At Columbia he was a member of the Phi Delta Theta fraternity. He could not play intercollegiate baseball for the Columbia Lions because he played baseball for a summer professional league before his freshman year. At the time he was unaware that doing so jeopardized his eligibility to play any collegiate sport. Gehrig was ruled eligible to play on the Lions' football team in 1922 and played first base and pitched for the university's baseball team the next year. In 1923, Paul Krichell, a scout, was so impressed with Gehrig that he offered him a contract with a $1,500 bonus to play for the Yankees. Gehrig signed with the Yankees despite his parent's hopes that he would become an engineer or architect. Gehrig couldn't ignore the money that would help with his parents financial and medical problems.

Major League Baseball Career

Gehrig joined the Yankees midway through the 1923 season and made his debut on June 15, 1923 as a pinch hitter. In his first two seasons Gehrig saw limited playing time, mostly as a pinch hitter—he played in only 23 games and was not on the Yankees' 1923 World Series-winning roster.

Gehrig’s first year of significant playing time in the Major League occurred in 1925. It was on June 1, 1925, that Gehrig’s consecutive-games-played streak began. In that first season, Gehrig had 437 official at-bats and compiled a very respectable .295 batting average with 20 home runs and 68 runs batted in (RBIs).

Gehrig's breakout season would come in 1926. He batted .313 with 47 doubles, an American League-leading 20 triples, 16 home runs, and 112 RBIs. In the 1926 World Series against the St. Louis Cardinals, Gehrig hit .348 with two doubles and 4 RBIs. The Cardinals won the seven-game series, however, four games to three.

In 1927, Gehrig put up one of the greatest seasons by any batter. That year he hit .373 with 218 hits. He had 52 doubles, 20 triples, 47 home runs, 175 RBIs, and a .765 slugging average. His 117 extra-base hits that season were second all-time to Babe Ruth’s 119 extra base hits and his 447 total bases were third all-time to Babe Ruth's 457 total bases in 1921 and Rogers Hornsby's 450 in 1922. Gehrig's great season helped the 1927 Yankees to a 110–44 record, the AL pennant, and a 4-game sweep over the Pittsburgh Pirates in the World Series. Although the AL recognized his season by naming him the league's Most Valuable Player (MVP), his season was overshadowed by Babe Ruth’s 60 home run season and the overall dominance of the 1927 Yankees, a team often cited as the greatest team of all-time.

Gehrig established himself as a bona fide star in his own right despite playing in the omnipresent shadow of Ruth for two-thirds of his career. Gehrig became one of the greatest run producers in baseball history. His 500+ RBIs over three consecutive seasons (1930–1932) set a Major League record. He had six seasons where he batted .350 or better (with a high of .379 in 1930), eight seasons with 150 or more RBIs, and 11 seasons with over 100 walks, eight seasons with 200 or more hits, and five seasons with more than 40 home runs. He led the American League in runs scored four times, home runs three times, and RBIs five times; his 184 RBIs in 1931 set an American League record (and was second all-time to Hack Wilson's 190 RBIs in 1930).

In the shadow of Ruth

Together, Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig were one of the most feared hitting tandem of their time. During the 10 seasons (1925–1934) in which Gehrig and Ruth were both Yankees and played a majority of games, Gehrig only had more home runs in 1934, when he hit 49 compared to Ruth’s 22. (Ruth played 125 games that year.) They tied at 46 in 1931. Ruth had 424 homers compared to Gehrig’s 347, some 22.2 percent more. Gehrig had more RBIs in seven years (1925, 1927, 1930–1934) and they tied in 1928. Ruth had 1,316 RBIs compared to Gehrig’s 1,436, with Gehrig having 9.9 percent more. Gehrig had more hits in eight years (1925, 1927–1928, 1930–1934). Gehrig had a higher slugging average in two years (1933–1934). And Gehrig had a higher batting average in seven years (1925, 1927–1928, 1930, 1932–1934). For that span, Gehrig had a .343 batting average, compared to .338 for Ruth.

Gehrig never made more than a third of Ruth's salary. His achievements were frequently eclipsed by other events. Gehrig's four-homer game at Shibe Park in Philadelphia in June 1932 was overshadowed by the retirement of legendary Giants manager John McGraw that same day. Gehrig's two homers in a 1932 World Series game in Chicago were forgotten in the legend of Ruth's mythic "called shot" homer the same day. After Ruth retired in 1935, a new superstar named Joe DiMaggio took the New York spotlight in 1936, leaving Gehrig to play in the shadow of yet another star.

2,130 Consecutive Games

On June 1, 1925, Gehrig was sent in to pinch hit for light-hitting shortstop Paul "Pee Wee" Wanninger. The next day, June 2, Yankee manager Miller Huggins started Gehrig in place of regular first baseman Wally Pipp. Pipp was in a slump, as were the Yankees as a team, so Huggins made several lineup changes to boost their performance. No one could have imagined that 14 years later Gehrig would still be there, playing day after day through injury and illness.

In a few instances, Gehrig managed to keep the streak intact through pinch hitting appearances and fortuitous timing; in others, the streak continued despite injuries. Late in life, X-rays disclosed that Gehrig had sustained a number of fractures during his playing career. Some examples:

- On April 23, 1933, Washington Senators pitcher Earl Whitehall hit Gehrig in the head with a pitch, knocking him nearly unconscious. Still, Gehrig recovered and was not removed from the game.

- On June 14, 1933, Gehrig was ejected from the game, along with manager Joe McCarthy, but had already been at bat, so he got credit for playing the game.

- On July 13, 1934, Gehrig suffered a "lumbago attack" and had to be assisted off the field. In the next day's away game, he was listed in the lineup as "shortstop," batting lead-off. In his first and only plate appearance, he singled and was promptly replaced by a pinch runner to rest his throbbing back, never actually taking the field.

- Late in his career, doctors X-rayed Gehrig's hands and spotted 17 fractures that had "healed" while Gehrig had continued playing.

Gehrig's record of 2,130 consecutive games played stood for 56 years. Baltimore Orioles shortstop Cal Ripken, Jr. played in his 2,131st consecutive game on September 6, 1995 in Baltimore, Maryland to establish a new record.

Marriage

In 1932, approaching the age of 30, Gehrig overcame his shyness and began to court Eleanor Grace Twitchell, the daughter of Chicago Parks Commissioner Frank Twitchell.

They were married by the mayor of New Rochelle on September 29, 1933 in a private ceremony. His mother showed her displeasure with Eleanor by not coming to the wedding. After the wedding, Gehrig played a baseball game. His mother, but not his father, did come to the reception that night. Bill Dickey, the great catcher, was the only Yankee teammate invited and present.

Eleanor was his opposite: a partygoer, a drinker, and very outgoing. She would end up having a profound influence on his career in their eight short years of marriage. She took on the role of Gehrig's manager, agent, and promoter in an era before every player had these positions on their payroll. She would also become a great source of strength in his battle with a debilitating disease.

Illness and the End of a Career

During the 1938 season, Gehrig's performance began to diminish. At the end of that season, he said, "I tired mid-season. I don't know why, but I just couldn't get going again." Although his final 1938 stats were respectable (.295 batting average, 114 RBIs, 170 hits, .523 slugging average, 758 plate appearances with only 75 strikeouts, and 29 home runs), it was a dramatic drop from his 1937 season (when he batted .351 and slugged at .643).

When the Yankees began their 1939 spring training in St. Petersburg, Florida, it was obvious that Gehrig no longer possessed his once-formidable power. Even Gehrig's base running was affected. Throughout his career Gehrig was considered an excellent runner on the base paths, but as the 1939 season got underway, his coordination and speed had deteriorated significantly.

By the end of April his statistics were the worst of his career, with just 1 RBI and an anemic .143 batting average. Fans and the press openly speculated on Gehrig's abrupt decline.

Joe McCarthy, the Yankees’ manager, was facing increasing pressure from Yankee management to switch Gehrig to a part-time role, but he could not bring himself to do it. Things came to a head when Gehrig had to struggle to make a routine put-out at first base. The pitcher, Johnny Murphy, had to wait for Gehrig to drag himself over to the bag so he could catch Murphy's throw. Murphy said, "Nice play, Lou." That was the thing Gehrig dreaded—his teammates felt they had to congratulate him on simple chores like put-outs, like older brothers patting their little brother on the head.

On April 30 Gehrig went hitless against the weak Washington Senators. Gehrig had just played his 2,130th consecutive Major League game.

On May 2, the next game after a day off, Gehrig approached McCarthy before the game and said, "I'm benching myself, Joe." McCarthy acquiesced and put Ellsworth "Babe" Dahlgren in at first base, and also said that whenever Gehrig wanted to play again, the position was his. Gehrig himself took the lineup card out to the shocked umpires before the game, ending the amazing 14-year stamina streak. When the stadium announcer told the fans that Lou Gehrig’s consecutive-games-played streak had come to an end at 2,130 games, the Detroit fans gave Gehrig a standing ovation while he sat on the bench with tears in his eyes.

Gehrig stayed with the Yankees as team captain for a few more weeks, but never played baseball again.

Diagnosis of ALS

As Lou Gehrig's debilitation became steadily worse, Eleanor called the famed Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. Her call was immediately transferred to Dr. Charles William Mayo, who had been following Gehrig's career and his mysterious loss of strength. Dr. Mayo told Eleanor to bring Gehrig as soon as possible.

Eleanor and Lou flew to Rochester from Chicago, where the Yankees were playing at the time, arriving at the Mayo Clinic on June 13, 1939. After six days of extensive testing at the Mayo Clinic, the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis ("ALS") was confirmed on June 19, Gehrig's 36th birthday.[3] The prognosis was grim: rapidly increasing paralysis, difficulty in swallowing and speaking, and a life expectancy of fewer than three years, although there would be no impairment of mental functions. Gehrig was told that the cause of ALS was unknown but it was painless, non-contagious, and cruel—the nervous system is destroyed but the mind remains intact.

Following Gehrig's visit to the Mayo Clinic, he briefly rejoined the Yankees in Washington, DC. As his train pulled into Union Station, he was greeted by a group of Boy Scouts, happily waving and wishing him luck. Gehrig waved back, but leaned forward to his companion, a reporter, and said, "They're wishing me luck…and I'm dying."[3]

"The Luckiest Man on the Face of the Earth"

On June 21, the New York Yankees announced Gehrig's retirement and proclaimed July 4, 1939, "Lou Gehrig Day" at Yankee Stadium. Between games of the Independence Day doubleheader against the Washington Senators, the poignant ceremonies were held on the diamond. Dozens of people, including many from other Major League teams, came forward to give Gehrig gifts and to shower praise on the dying slugger. The 1927 World Championship banner, from Gehrig's first World Series win, was raised on the flagpole, and the members of that championship team, known as "Murderer's Row," attended the ceremonies. New York Mayor Fiorello H. LaGuardia and the postmaster general were among the notable speakers, as was Babe Ruth.

Joe McCarthy, struggling to control his emotions, then spoke of Lou Gehrig, with whom there was a close, almost father and son-like bond. After describing Gehrig as "the finest example of a ballplayer, sportsman, and citizen that baseball has ever known," McCarthy could stand it no longer. Turning tearfully to Gehrig, the manager said, "Lou, what else can I say except that it was a sad day in the life of everybody who knew you when you came into my hotel room that day in Detroit and told me you were quitting as a ballplayer because you felt yourself a hindrance to the team. My God, man, you were never that."

The Yankees retired Gehrig's uniform number "4," making him the first player in history to be afforded that honor. Gehrig was given many gifts, commemorative plaques, and trophies. Some came from VIPs; others came from the stadium's groundskeepers and janitorial staff. The Yankees gave him a silver trophy with their signatures engraved on it. Inscribed on the front was a special poem written by New York Times writer John Kieran.

After the presentations, Gehrig took a few moments to compose himself, then approached the microphone, and addressed the crowd:

Look at these grand men. Which of you wouldn't consider it the highlight of his career just to associate with them for even one day? Sure, I'm lucky. Who wouldn't consider it an honor to have known Jacob Ruppert? Also, the builder of baseball's greatest empire, Ed Barrow? To have spent six years with that wonderful little fellow, Miller Huggins? Then to have spent the next nine years with that outstanding leader, that smart student of psychology, the best manager in baseball today, Joe McCarthy? Sure, I'm lucky.

When the New York Giants, a team you would give your right arm to beat, and vice versa, sends you a gift—that's something. When everybody down to the groundskeepers and those boys in white coats remember you with trophies—that's something. When you have a wonderful mother-in-law who takes sides with you in squabbles with her own daughter—that's something. When you have a father and a mother who work all their lives so you can have an education and build your body—it's a blessing. When you have a wife who has been a tower of strength and shown more courage than you dreamed existed—that's the finest I know.

So I close in saying that I may have had a tough break, but I have an awful lot to live for.[4]

The crowd stood and applauded for almost two minutes. Gehrig was visibly shaken as he stepped away from the microphone, and wiped the tears away from his face with his handkerchief. Babe Ruth came over and hugged him, in a memorable moment forever engraved in baseball lore.

Later that year, the Baseball Writers Association elected Lou Gehrig to the National Baseball Hall of Fame, waiving the mandatory five-year waiting period. At age 36 he was the youngest player to be so honored.

The Final Years after Baseball

"Don't think I am depressed or pessimistic about my condition at present," Lou Gehrig wrote following his retirement from baseball. Struggling against his ever worsening physical condition, he added, "I intend to hold on as long as possible and then if the inevitable comes, I will accept it philosophically and hope for the best. That's all we can do."[3]

In October 1939, he accepted Mayor of New York Fiorello H. LaGuardia's appointment to a ten-year term as a New York City Parole Commissioner. Behind the glass door to his office, lettered "Commissioner Gehrig," he met with many poor and struggling people of all races, religions, and ages, some of whom would complain that they just "got a bad break." Gehrig never scolded them or preached about what a "bad break" really was. He visited New York City's correctional facilities, but insisted that his visits not be covered by news media. To avoid any appearance of grandstanding, Gehrig made sure his listing on letterhead, directories, and publications read simply, "Henry L. Gehrig."[5]

Death and Legacy

On June 2, 1941, 16 years to the day after he replaced Wally Pipp at first base to begin his 2,130 consecutive-games-played streak, Henry Louis Gehrig died at his home at 5204 Delafield Avenue in Riverdale, which is part of the Bronx, New York. He was 37 years old. Upon hearing the news, Babe Ruth and his wife Claire immediately left their Riverside Drive apartment on Manhattan's upper west side and went to the Gehrig's house to console Eleanor. Mayor Fiorello H. LaGuardia ordered flags in New York to be flown at half-staff and Major League ballparks around the nation did likewise.[6]

Following the funeral at Christ Episcopal Church of Riverdale, Gehrig's remains were cremated and interred on June 4 at Kensico Cemetery in Valhalla, New York. As a coincidence, Lou Gehrig and Ed Barrow are both interred in the same section of Kensico Cemetery, which is next door to Gate of Heaven Cemetery, where the graves of Babe Ruth and Billy Martin are located.

Eleanor Gehrig never remarried following her husband's passing, dedicating the rest of her life to supporting ALS research.[2] She died in 1984, at the age of 80. She was cremated and buried beside her husband.

The Yankees dedicated a monument to Gehrig in center field at Yankee Stadium on July 6, 1941, the shrine lauding him as, "A man, a gentleman and a great ballplayer whose amazing record of 2,130 consecutive games should stand for all time." Gehrig's monument joined the one placed there in 1932 for Miller Huggins, which would eventually be followed by Babe Ruth's in 1949. Upon Gehrig's monument rests an actual bat used by him, now bronzed.

Gehrig's birthplace in Manhattan on East 94th Street (between 1st and 2nd avenues) is memorialized with a plaque marking the site. The Gehrig's house at 5204 Delafield Ave. in the Bronx where Lou Gehrig died still stands today on the east side of the Henry Hudson Parkway and is likewise marked by a plaque.

In 1942, the life of Lou Gehrig was immortalized in the movie, The Pride of the Yankees, starring Gary Cooper as Lou Gehrig and Teresa Wright as his wife Eleanor. It received 11 Academy Award nominations and won one Oscar. Real-life Yankees Babe Ruth, Bob Meusel, Mark Koenig, and Bill Dickey, then still an active player, played themselves, as did sportscaster Bill Stern.

Career Statistics

| G | AB | H | 2B | 3B | HR | R | RBI | BB | SO | SH | HBP | AVG | OBP | SLG |

| 2164 | 8,001 | 2,721 | 534 | 163 | 493 | 1,888 | 1,995 | 1,508 | 790 | 106 | 45 | .340 | .447 | .632 |

Notes

- ↑ Ray Robinson. Iron Horse: Lou Gehrig in His Time. (New York: Harper, 1991).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 William Kashatus. Lou Gehrig: A Biography. (Westport CT: Greenwood Press, 2004).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Jonathan Eig. Luckiest Man: The Life and Death of Lou Gehrig. (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005).

- ↑ Estate of Eleanor Gehrig, The Farewell Speech, The Official Website of Lou Gehrig. Retrieved July 10, 2007.

- ↑ The Webmaster, New York City Parole Commission History, New York Correction History Society. Retrieved July 10, 2007. In appointing Gehrig as a Parole Commissioner, Mayor LaGuardia said, "I believe he will be not only a capable, intelligent commissioner but that he will be an inspiration and a hope to many of the younger boys who have gotten into trouble. Surely the misfortune of some of the young men will compare as something trivial with what Mr. Gehrig has so cheerfully and courageously faced." Gehrig continued to go regularly to his city hall office until a month before his death.

- ↑ TIME, In Memoriam, June 16, 1941. Retrieved July 10, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brunsvold, Sara Kaden. The Life of Lou Gehrig: Told by a Fan. Skokie, IL: ACTA Sports, 2006. ISBN 9780879462987

- Eig, Jonathan. Luckiest Man: The Life and Death of Lou Gehrig. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005. ISBN 0743245911

- Estate of Eleanor Gehrig. The Official Website of Lou Gehrig. Retrieved July 10, 2007.

- Gehrig, Eleanor, and Joseph Durso. 1976. My Luke and I. New York: Crowell. ISBN 0690011091

- Kashatus, William C. Lou Gehrig: a Biography. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2004. ISBN 0313328668

- Newman, Mark. Gehrig's Shining Legacy of Courage. MLB.com. Retrieved July 10, 2007.

- Robinson, Ray. Iron Horse: Lou Gehrig in His Time. New York: W.W. Norton, 1990. ISBN 0393028577

External links

All links retrieved March 13, 2025.

- Video, Audio, and Text of Lou Gehrig's Farewell to Baseball Address

- Lou Gehrig at BaseballReference.com

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.