Malacostraca

| Malacostraca | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||

| ||||||||

|

Eumalacostraca |

Malacostraca is a large and diverse taxon (generally class, but sometimes subclass or order) of marine, freshwater, and terrestrial crustaceans, including many of the most familiar crustaceans, such as crabs, lobsters, shrimps, which are characterized by a maximum of 19 pairs of appendages, as well as trunk limbs that are sharply differentiated into a thoracic series and an abdominal series. Other familiar members of the Malacostraca are the stomatopods (mantis shrimp) and euphausiids (krill), as well as the amphipods, and the only substantial group of land-based crustaceans, the isopods (woodlice and related species). With more than 22,000 members, this group represents two thirds of all crustacean species and contains all the larger forms.

This is a very diverse group of crustaceans. They also are a very important group. Ecologically, they serve an important function in food chains, providing an important source of nutrition for fish, mammals, birds, and mollusks, among others. Commercially, many of the larger species are an important source of food and support billions in dollars in trade.

Overview and description

The taxonomic status of the crustaceans has long been debated, with Crustacea variously assigned to the rank of phylum, subphylum, and superclass level. As a result, the taxonomic status of Malacostraca is not settled, generally being considered a class within the subphylum or superclass Crustacea, but sometimes considered as an order or subclass under the class Crustacea.

As crustaceans, members of Malacostraca are characterized by by having branched (biramous) appendages, an exoskeleton made up of chitin and calcium, two pairs of antennae that extend in front of the mouth, and paired appendages that act like jaws, with three pairs of biting mouthparts. They share with other arthropods the possession of a segmented body, a pair of jointed appendages on each segment, and a hard exoskeleton that must be periodically shed for growth.

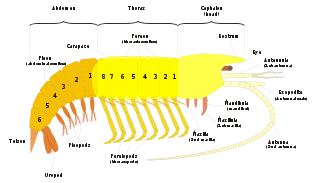

Members of Malacostraca are united by generally having a maximum of 19 pairs of appendages, and by having trunk limbs differentiated into an abdominal series and thoracic series, with the former having six pairs and the later eight pairs of limbs. Typical characteristics include:

- The head has 6 segments, with a pair of antennules and a pair of antennae, as well as mouthparts.

- They usually have 8 pairs of thoracic legs, of which the first pair or several pairs are often modified into feeding appendages called maxillipeds. The first pair of legs behind the maxillipeds is often modified into pincers.

- There are 8 thoracic segments. The cephalothorax is covered by a carapace form via fusion of 3 of them, letting the 5 other uncovered.

- The abdomen is behind and often used for swimming. There are 6 abdominal segments.

- They have compound stalked or sessile eyes.

- The female genital duct opens at the sixth thoracic segment; the male genital duct opens at the eighth thoracic segment.

- They have a two-chambered stomach.

- They have a centralized nervous system.

However, this is a very diverse group. Although the term Malacostraca comes from the Greek for "soft shell," the shell of different species may be large, small, or absent. Likewise, the abdomen may be long or short, and the eyes may show different forms, being on movable stalks or sessile.

Classification

Generally, three main subclasses are recognized: Eumalacostraca, Hoplocarida, and Phyllocarida.

Eumalacostraca. The subclass Eumalacostraca (Greek: "True soft shell") contains almost all living malacostracans. Eumalacostracans have 19 segments (5 cephalic, 8 thoracic, 6 abdominal). The thoracic limbs are jointed and used for swimming or walking. The common ancestor is thought to have had a carapace, and most living species possess one, but it has been lost in some subgroups.

Phyllocarida. The subclass Phyllocarida has one extant order, Leptostraca. These are typically small, marine crustaceans, generally 5 to 15 millimeters long (Lopretto 2005). They possess a head with stalked compound eyes, two pairs of antennae (one biramous, one uniramous) and a pair of mandibles but no maxilliped (Lowry 1999). The carapace is large and comprises two valves which cover the head and the thorax, including most of the thoracic appendages, and houses as a brood pouch for the developing embryos. The abdomen has eight segments, six of which bear pleopods, and a pair of caudal furcae, which may be homologous to uropods of other crustaceans (Knopf et al. 2006). Members of this subclass occur throughout the world's oceans and are usually considered to be filter-feeders.

Hoplocarida. The subclass Hoplocarida includes the extant order Stomatopoda. Stomatopods, known by the common name of mantis shrimp, are marine crustaceans. They are neither shrimp nor mantids, but receive their name purely from the physical resemblance to both the terrestrial praying mantis and the shrimp. They may reach 30 centimeters (12 inches) in length, although exceptional cases of up to 38 centimeters have been recorded (Gonser 2003). The carapace of mantis shrimp covers only the rear part of the head and the first three segments of the thorax. Mantis shrimp sport powerful claws that they use to attack and kill prey by spearing, stunning, or dismemberment. These aggressive and typically solitary sea creatures spend most of their time hiding in rock formations or burrowing intricate passageways in the sea-bed. They either wait for prey to chance upon them or, unlike most crustaceans, actually hunt, chase, and kill living prey. They rarely exit their homes except to feed and relocate, and can be diurnal, nocturnal or crepuscular, depending on the species. Most species live in tropical and subtropical seas (Indian and Pacific Oceans between eastern Africa and Hawaii), although some live in temperate seas.

Martin and Davis (2001) present the following classification of living malacostracans into orders, to which extinct orders have been added, indicated by †.

Class Malacostraca Latreille, 1802

- Subclass Phyllocarida Packard, 1879

- †Order Archaeostraca

- †Order Hoplostraca

- †Order Canadaspidida

- Order Leptostraca Claus, 1880

- Subclass Hoplocarida Calman, 1904

- Order Stomatopoda Latreille, 1817 (mantis shrimp)

- Subclass Eumalacostraca Grobben, 1892

- Superorder Syncarida Packard, 1885

- †Order Palaeocaridacea

- Order Bathynellacea Chappuis, 1915

- Order Anaspidacea Calman, 1904

- Superorder Peracarida Calman, 1904

- Order Spelaeogriphacea Gordon, 1957

- Order Thermosbaenacea Monod, 1927

- Order Lophogastrida Sars, 1870

- Order Mysida Haworth, 1825 (opossum shrimp)

- Order Mictacea Bowman, Garner, Hessler, Iliffe & Sanders, 1985

- Order Amphipoda Latreille, 1816

- Order Isopoda Latreille, 1817 (woodlice, slaters)

- Order Tanaidacea Dana, 1849

- Order Cumacea Krøyer, 1846 (hooded shrimp)

- Superorder Eucarida Calman, 1904

- Order Euphausiacea Dana, 1852 (krill)

- Order Amphionidacea Williamson, 1973

- Order Decapoda Latreille, 1802 (crabs, lobsters, shrimp)

- Superorder Syncarida Packard, 1885

The phylogeny of Malacostraca is debated (Schram 1986). Recent molecular studies, 18S (Meland and Willassen 2007) and 28S (Jarman et al. 2000), have even disputed the monophyly of the Peracarida by removing the Mysida and have firmly rejected the monophyly of the Edriophthalma (Isopoda and Amphipoda) and the Mysidacea (Mysida, Lophogastrida, and Pygocephalomorpha).

The first malacostracans appeared in the Cambrian.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Gonser, J. 2003. Large shrimp thriving in Ala Wai Canal muck. Honolulu Advertiser February 14, 2003. Retrieved November 9, 2008.

- Hobbs, H. H. 2003. Crustacea. In Encyclopedia of Caves and Karst Science. Routledge. Retrieved November 9, 2008.

- Jarman, S. N., S. Nicol, N. G. Elliott, and A. McMinn. 2000. 28S rDNA Evolution in the Eumalacostraca and the phylogenetic position of krill. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 17(1): 26–36.

- Knopf, F., S. Koenemann, F. R. Schram, and C. Wolff. 2006. The urosome of the Pan- and Peracarida. Contributions to Zoology 75(1/2): 1–21. Retrieved November 9, 2008.

- Lopretto, E. C. 2005. Phyllocarida. In D. E. Wilson, and D. M. Reeder (eds.), Mammal Species of the World, 3rd edition. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801882214.

- Lowry, J. K. 1999. Crustacea, the higher taxa: Leptostraca (Malacostraca). Australian Museum. Retrieved November 9, 2008.

- Martin, J. W., and G. E. Davis. 2001. An Updated Classification of the Recent Crustacea. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Retrieved November 9, 2008.

- Meland, K., and E. Willassen. 2007. The disunity of “Mysidacea” (Crustacea). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 44: 1083–1104.

- Schram, F. R. 1986. Crustacea. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195037421.

| |||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.