| Modoc | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Toby "Winema" Riddle (Modoc, 1848–1920) | ||||||

| Total population | ||||||

| 800 (2000) | ||||||

| Regions with significant populations | ||||||

| ||||||

| Languages | ||||||

| English, formerly Modoc | ||||||

| Religions | ||||||

| Related ethnic groups | ||||||

| Klamath, Yahooskin |

The Modoc are a Native American people who originally lived in the area which is now northeastern California and central Southern Oregon. They are currently divided between Oregon and Oklahoma where they are enrolled in either of two federally recognized tribes, the Klamath Tribes in Oregon and the Modoc Tribe of Oklahoma. Modoc Plateau, Modoc National Forest, Modoc County, California, Modoc, Indiana, and numerous other places are named after this group of people.

Historically, the Modoc are most known for the Modoc War between a Modoc band led by Kintpuash (also known as Captain Jack) and the United States Army in 1872 to 1873. This band had broken the treaty signed by the Modoc and left the Indian reservation where they had suffered ill treatment. The ensuing violence shocked the nation which had been following President Ulysses S. Grant's peace policy which advocated Native American education and recommended use of Indian reservations to protect them from settler intrusion. The Modoc were eventually defeated and Kintpuash and other leaders were found guilty of war crimes and executed.

Contemporary Modoc are proud of their heritage and are engaged in projects to document their history and recover their language and traditions. They have developed a number of businesses, including casinos, as well as promoting lifestyles and businesses that support the environment as well as re-introducing bison into their reservation lands.

History

Pre-contact

Estimates for the pre-contact populations of most native groups in California, including the Modoc, have varied substantially. James Mooney put the aboriginal population of the Modoc at 400.[1] Alfred L. Kroeber estimated the 1770 Modoc population within California as 500.[2] University of Oregon anthropologist Theodore Stern suggested that there had been a total of about 500 Modoc.[3]

Known Modoc village sites are Agawesh where Willow Creek enters Lower Klamath Lake, Kumbat and Pashha on the shores of Tule Lake, and Wachamshwash and Nushalt-Hagak-ni on the Lost River.[4]

In addition to the Klamath, with whom they shared a language and the Modoc Plateau, the groups neighboring the Modoc homelands were the following:

- Shasta on the Klamath River;

- Rogue River Athabaskans and Takelma west over the Cascade Mountains;

- Northern Paiute east in the desert;

- Karuk and Yurok further down the Klamath River; and

- Achomawi or Pit River to the south, in the meadows of the Pit River drainages.

The Modoc, Northern Paiute, and Achomawi shared Goose Lake Valley.[5]

First contact

In the 1820s, Peter Skene Ogden, an explorer for the Hudson's Bay Company, established trade with the Klamath people to the north of the Modoc.

Lindsay Applegate, accompanied by fourteen other settlers in the Willamette and Rogue valleys in western Oregon, established the South Emigrant Trail in 1846. It connected a point on the Oregon Trail near Fort Hall, Idaho and the Willamette Valley. Applegate and his party were the first known white men to enter what is now the Lava Beds National Monument. On their exploring trip eastward, they attempted to pass around the south end of Tule Lake, but the rough lava along the shore forced them to seek a route around the north end of the lake. The Modoc inhabited the region around Lower Klamath Lake, Tule Lake, and the Lost River in northern California and southern Oregon. The opening of the South Emigrant Trail brought the first regular contact between the Modoc and the European-American settlers, who had largely ignored their territory before. Many of the events of the Modoc War took place along the South Emigrant Trail.

Until this time the Modoc had been hunter-gatherers who were detached from their neighbors, apart from occasional raids or war parties to drive out intruders. With the arrival of settlers who passed directly through their lands, the Modoc were forced to change their ways. At first they were able to barter with the newcomers. However, as more settlers arrived who took over their land, relationships became strained.[6]

In 1847 the Modoc, under the leadership of Old Chief Schonchin, began raiding the settlers traveling on the Oregon Trail as they passed through Modoc lands. In September 1852, the Modoc destroyed an emigrant train at Bloody Point on the east shore of Tule Lake. In response, Ben Wright, a notorious Indian hater,[7] Accounts differ as to what took place when Wright's party met the Modoc on Lost River, but most agree that Wright planned to ambush them, which he did in November 1852. Wright and his forces attacked, killing approximately 40 Modoc, in what came to be known as the "Ben Wright Massacre."[8]

Treaty with the United States

With the increasing numbers of white settlers, the Klamath, Modoc, and Yahooskin band of Snake tribes signed a treaty with the United States government in 1864, establishing the Klamath Reservation, despite the fact that the Klamath and Modoc were traditional enemies. The treaty required the tribes to cede the land bounded on the north by the 44th parallel, on the west and south by the ridges of the Cascade Mountains, and on the east by lines touching Goose Lake and Henley Lake back up to the 44th parallel. In return, the United States was to make a lump sum payment of $35,000, and annual payments totaling $80,000 over 15 years, as well as providing infrastructure and staff for a reservation. The treaty provided that if the Indians drank or stored intoxicating liquor on the reservation, the payments could be withheld and that the United States could locate additional tribes on the reservation in the future. Lindsay Applegate was appointed as the US Indian agent. The total population of the three tribes was estimated at about 2,000 when the treaty was signed.

The terms of the 1864 treaty demanded that the Modoc surrender their lands in near Lost River, Tule Lake, and Lower Klamath Lake in exchange for lands in the Upper Klamath Valley. They did so, under the leadership of Chief Schonchin. The land of the reservation did not provide enough food for both the Klamath and the Modoc peoples. Illness and tension between the tribes increased. The Modoc requested a separate reservation closer to their ancestral home, but neither the federal nor the California government would approve it.

Kintpuash (also called Captain Jack) led a band of Modoc off the reservation and returned to their traditional homelands in California. They built a village near the Lost River where they remained for several years in violation of the treaty.

Modoc War

The Modoc War, or Modoc Campaign (also known as the Lava Beds War), was an armed conflict between the Modoc tribe and the United States Army in southern Oregon and northern California from 1872 to 1873.[9] The Modoc War was the last of the Indian Wars to occur in California or Oregon. Eadweard Muybridge photographed the early part of the campaign.

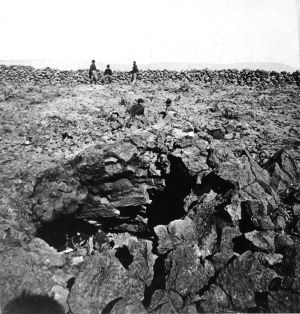

Captain Jack had led 52 warriors in a band of more than 150 Modoc people off the Klamath Reservation and established a village at Lost River. In November 1872, the U.S. Army was sent to Lost River to attempt to force this band back to the reservation. A battle broke out, and the Modoc escaped to what is called Captain Jack's Stronghold in what is now Lava Beds National Monument, California. Occupying defensive positions throughout the lava beds south of Tule Lake, the small band of warriors was able to hold off the 3,000 troops of the U.S. Army for several months, defeating them in combat several times.

For some months, Captain Jack had boasted that in the event of war, he and his band could successfully defend themselves in an area in the lava beds on the south shore of Tule Lake. The Modoc retreated there after the Battle of Lost River. Today it is called Captain Jack's Stronghold. The Modoc took advantage of the lava ridges, cracks, depressions, and caves, all such natural features being ideal from the standpoint of defense. At the time the 52 Modoc warriors occupied the Stronghold, Tule Lake bounded the Stronghold on the north and served as a source of water.

President Grant had decided to act upon Meacham's original suggestion of several years earlier to give the Modoc their own reservation, separate from the Klamath. With Kintpuash's band entrenched in the Lava Beds, negotiation was not easy. A cousin of Kintpuash, Winema, had married Frank Riddle, a white settler, taking the name Toby Riddle. Toby's grasp of the English language and her understanding of the white man's world allowed her to act in the capacity of both interpreter and mediator. In March of 1873, a committee was formed consisting of Alfred Meacham, Leroy Dyar, Rev. Eleazar Thomas, Gen. Edward R.S. Canby, and Winema and Frank Riddle.[10] Their responsibility was to convince the Lava Bed Modocs to return and set up a new reservation.

For several months Winema traveled through the Lava Beds carrying messages back and forth. As she was leaving the Lava Beds in early April of 1873, she was followed by one of Kintpuash' men, who informed her of a plot to kill the peace commissioners during the face-to-face which was scheduled for April 11—Good Friday. Winema relayed this information to Canby and Meacham and urged them to forgo the meeting. However, they failed to heed her warning and went on with the meeting as planned.

Though Kintpuash had been pressured into killing the commissioners, he tried one final time to negotiate more favorable terms for his tribe. However, it soon became clear that the commissioners were not willing to negotiate and simply wanted the Modocs to surrender. As the meeting became more heated, Winema attempted to intervene and settle things peacefully. From the Modoc's point of view they had no choice but to go forward with their original plan of assault and they opened fire on the commissioners. In the skirmish, Canby and Thomas died, Meacham was severely wounded, and Dyar and Frank Riddle escaped. The killing of the peace commissioners made national and international news. For the Modocs it meant two more months of fighting and eventual surrender as the army closed in.[10]

After more warfare with reinforcements of US forces, the Modoc left the Stronghold and began to splinter. Kintpuash and his group were the last to be captured on June 4, 1873, when they voluntarily gave themselves up. The U.S. government personnel had assured them that their people would be treated fairly and that the warriors would be allowed to live on their own land.

After the war

Captain Jack, Schonchin John, Black Jim, Boston Charley, Brancho (Barncho), and Slolux were tried by a military court for the murders of Major General Edward Canby and Reverend Thomas, and attacks on Meacham and others. The six Modoc were convicted, and sentenced to death. On September 10, President Ulysses S. Grant approved the death sentence for Captain Jack, Schonchin John, Black Jim, and Boston Charley; Brancho and Slolux were committed to life imprisonment on Alcatraz. Grant ordered that the remainder of Captain Jack's band be held as prisoners of war. On October 3, 1873, Captain Jack and his three lead warriors were hanged at Fort Klamath.

The Army sent the remaining 153 Modoc of the band to the Quapaw Agency in Indian Territory as prisoners of war with Scarfaced Charley as their chief. The tribe's spiritual leader, Curley Headed Doctor, also made the removal to Indian Territory.[11] In 1909, after Oklahoma had become a state, members of the Modoc Tribe of Oklahoma were offered the chance to return to the Klamath Reservation. Twenty-nine people returned to Oregon; these Modoc of Oregon and their descendants became part of the Klamath Tribes Confederation. Most Modoc (and their descendants) stayed in what was then the state of Oklahoma. As a result, there are federally recognized Modoc tribes in Oregon and Oklahoma today.

Historian Robert Utley has argued that the Modoc War, and the Great Sioux War a few years later, undermined public confidence in President Grant's peace policy, renewing public sentiment to use force against the American Indians in order to suppress them.[12]

Culture

Prior to the nineteenth century, when European explorers first encountered the Modoc, like all Plateau Indians they caught salmon and migrated seasonally to hunt and gather other food. During this season they lived in portable tents covered with mats. In winter, they built semi-underground earth lodges shaped like beehives, covered with sticks and plastered with mud, located near lake shores with reliable sources of seeds from aquatic woka plants and fishing.[5]

Language

The original language of the Modoc and that of the Klamath, their neighbors to the north, were branches of the family of Plateau Penutian languages. The Klamath and Modoc languages together are sometimes referred to as Lutuamian languages. Both peoples called themselves maklaks, meaning "people."

To distinguish between the tribes, the Modoc called themselves Moatokni maklaks, from muat meaning "South." The Achomawi, a band of the Pit River tribe, called the Modoc Lutuami, meaning "Lake Dwellers."[5]

Religion

The religion of the Modoc is not known in detail. The number five figured heavily in ritual, as in the Shuyuhalsh, a five-night dance rite of passage for adolescent girls. A sweat lodge was used for purification and mourning ceremonies.

Modoc oral literature is representative of the Plateau region, but with influences from the Northwest Coast, the Great Basin, and central California. Of particular interest are accounts supposedly describing the volcanic origin of Crater Lake in Oregon.

Contemporary Modoc

Contemporary Modoc are divided between Oregon and Oklahoma and are enrolled in either of two federally recognized tribes, the Klamath Tribes in Oregon[13] and the Modoc Tribe of Oklahoma.

About 600 members of the tribe currently live in Klamath County, Oregon, in and around their ancestral homelands. This group includes the Modoc families who stayed on the reservation during the Modoc War, as well as the descendants of those who chose to return to Oregon from Oklahoma in 1909. Since that time, many of them have followed the path of the Klamath. The shared tribal government of the Klamath, Modoc, and Yahooskin in Oregon is known as the Klamath Tribes.

The Modoc Tribe of Oklahoma is the smallest federally recognized tribe in Oklahoma.[14] They are descendants of Captain Jack's band of Modoc people, removed from the West Coast after the Modoc Wars to the Quapaw Indian Reservation at the far northeast corner of Oklahoma. The Modoc Tribe of Oklahoma, headquartered in Miami, Oklahoma, was officially recognized by the United States government in 1978, and their constitution was approved in 1991. Of the 250 enrolled tribal members, 120 live within the state of Oklahoma. The Tribe's Chief is Bill Follis, who was instrumental in securing federal re-recognition.[6]

The Oklahoma Modocs operate their own housing authority, a casino, a tribal smoke shop, Red Cedar Recycling, and the Modoc Bison Project as a member of the Inter-Tribal Bison Cooperative. They also issue their own tribal license plates. The Stables Casino is located in Miami, Oklahoma, and includes a restaurant and gift shop.[15] Tribally-owned Red Cedar Recycling provides free cardboard and paper recycling for area businesses and residents and pays market rate for aluminum to recycle. The tribal company also provides educational materials about recycling and hosts tire recycling events.[16] The Modoc Tribe has reintroduced buffalo to the prairie. The Modoc Bison Range, located on part of the original Modoc allotment land, hosts over 100 wild buffalo.[17]

Notes

- ↑ James Mooney, The Aboriginal Population of America North of Mexico (Washington DC: Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, 1928), 18.

- ↑ Alfred L. Kroeber, Handbook of the Indians of California (New York, NY: Dover Publications, Reprint edition, 2012, ISBN 978-0486233680), 883.

- ↑ Theodore Stern, "Klamath and Modoc" in Deward E. Walker (ed.), Handbook of North American Indians (Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press, 1998).

- ↑ Alfred L. Kroeber, Handbook of the Indians of California (New York, NY: Dover Publications, 2012, ISBN 978-0486233680), 305–335.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Robert W. Pease, Modoc County (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1965), 46–48.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Patrica Scruggs, Tribal History and Photos The Modoc Tribe of Oklahoma.

- ↑ William Samuel Brown, Chapter II, Early History Emigrant Trails and Indian Warfare History of the Modoc National Forest Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- ↑ Ben Wright Massacre of 1852. Retrieved May 24, 2013.

- ↑ Warren A. Beck and Ynez D. Hasse, The Modoc War, 1872 to 1873. California State Military Museum, first published in their Historical Atlas of California, used with permission of the University of Oklahoma Press, 1975. Retrieved May 25, 2013.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Rebecca Bales, Winema and the Modoc War: One Woman's Struggle for Peace. Prologue Magazine 37(1) (Spring 2005). Retrieved May 25, 2013.

- ↑ Dan Thrapp, Encyclopedia of Frontier Biography, Volume 1: A-F (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1991, ISBN 978-0803294189).

- ↑ Robert Marshall Utley, Frontier Regulars: The United States Army and the Indian, 1866-1891 (MacMillan Publishing Company, 1974, ISBN 978-0026212502).

- ↑ US Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, Appendix O Federally Recognized Indian Tribes with Interest in the Planning Area Western Oregon Plan Revision Final Environmental Impact Statement For the Revision of the Resource Management Plans of the Western Oregon Bureau of Land Management Districts (Portland, OR: Oregon State Office, Bureau of Land Management), 516–517. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- ↑ Burl E. Self, Modoc Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History & Culture. Retrieved May 21, 2013.

- ↑ The Stables. Retrieved May 21, 2013.

- ↑ Red Cedar Recycling. Modoc Tribe Office of Environmental Quality.

- ↑ Bison Range.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brown, William Samuel. History of the Modoc National Forest. ASIN B0007F5NK0 Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- James, Cheewa. Modoc: The Tribe That Wouldn't Die. Naturegraph Publishers, 2008. ISBN 978-0879612757

- Kroeber, Alfred L. Handbook of the Indians of California. New York, NY: Dover Publications, Reprint edition, 2012. ISBN 978-0486233680

- Mooney, James. The Aboriginal Population of America North of Mexico. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections No. 80(7), 1928. ASIN B000Z43VTI

- Murray, Keith A. The Modocs and Their War. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1976. ISBN 978-0806113319

- Payne, Doris P. Captain Jack, Modoc Renegade. Binford & Mort Pubs, 1979. ISBN 978-0832303401

- Pease, Robert W. Modoc County. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1965. ASIN B0007DNJF8

- Pritzker, Barry M. A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0195138771

- Quinn, Arthur. Hell With the Fire Out: A History of the Modoc War. New York, NY: Faber and Faber, 1997. ISBN 978-0571199037

- Riddle, Jefferson C. Davis. The Indian History of the Modoc War. Stackpole Books, 2004. ISBN 978-0811729772

- Smith, J. L. A Chronological History of the Oregon War - 1850-1878. Anchorage, AK: Whitestone Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1456485993

- Thrapp, Dan. Encyclopedia of Frontier Biography, Volume 1: A-F. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0803294189

- Utley, Robert Marshall. Frontier Regulars: The United States Army and the Indian, 1866-1891. MacMillan Publishing Company, 1974. ISBN 978-0026212502

- Waldman, Carl. Atlas of the North American Indian. New York, NY: Checkmark Books, 2000. ISBN 978-0816039753

- Waldman, Carl. Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes. New York, NY: Checkmark Books, 2006. ISBN 978-0816062744

- Walker, Deward E. (ed.). Handbook of North American Indians:Plateau 12. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0160495144

- Yenne, Bill. Indian Wars: The Campaign for the American West. Westholme Publishing, 2008. ISBN 978-1594160691

External links

All links retrieved November 9, 2022.

- Modoc Tribe of Oklahoma, official website

- Klamath Tribes: Klamath, Modoc, Yahooskin, official website

- Map of the campaigns during the Modoc War

- The Modoc War Documentary produced by Oregon Public Broadcasting

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.