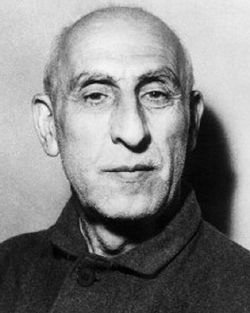

Mohammed Mosaddeq

| Mohammed Mosaddeq محمد مصدق | |

| |

Prime Minister of Iran

| |

| In office April 28, 1951 – August 19, 1953 | |

| Preceded by | Hossein Ala' |

|---|---|

| Succeeded by | Fazlollah Zahedi |

| Born | June 16 1882 Tehran |

| Died | 5 March 1967 (aged 84) |

| Political party | National Front |

| Religion | Islam |

Mohammad Mosaddeq (Mossadeq ▶) (Persian: محمد مصدق Moḥammad Moṣaddeq, also Mosaddegh or Mossadegh) (June 16, 1882 – March 5, 1967) was a major figure in modern Iranian history who served as the Prime Minister of Iran[1][2] from 1951 to 1953 when he was removed from power by a coup d'état. From an aristocratic background, Mosaddeq was a nationalist and passionately opposed foreign intervention in Iran. An author, administrator, lawyer, prominent parliamentarian, and statesman, he is most famous as the architect of the nationalization of the Iranian oil industry,[3] which had been under British control through the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC), today known as British Petroleum (BP).

Mosaddeq was removed from power on August 19, 1953, in a coup d'état, supported and funded by the British and U.S. governments and led by General Fazlollah Zahedi.[4] The American operation came to be known as Operation Ajax in America,[5] after its CIA cryptonym, and as the "28 Mordad 1332" coup in Iran, after its date on the Iranian calendar.[6] Mosaddeq was imprisoned for three years and subsequently put under house arrest until his death.

In Iran and many countries, Mosaddeq is known as a hero of Third World anti-imperialism and victim of imperialist greed.[7] However a number of scholars and historians believe that alongside the plotting of the UK and U.S., a major factor in his overthrow was Mossadeq’s loss of support among Shia clerics and the traditional middle class brought on by his increasingly radical and secular policies and by their fear of a communist takeover.[8][9][10][11] U.S.-British support for the dictatorial rule of the Shah and their role in overthrowing Mosaddeq's government has attracted censure as an example of duplicity. On the one hand, the U.S. and Great Britain spoke about their commitment to spreading democracy and to opposing tyranny; on the other hand, they appeared to compromise their principles when their own economic or strategic interests are threatened. With other example of these nations supporting non-democratic regimes, the legacy of the Mosaddeq coup makes the task of spreading freedom around the world harder to achieve, since the real intent of intervention by the Western powers, when this occurs, can be questioned.[12]

Early life

Mosaddeq was born in 1882 in Tehran to an Ashtian Bakhtiari finance minister, Mirza Hideyatu'llah Khan (d. 1892) and a Qajar princess, Shahzadi Malika Taj Khanum (1858-1933). By his mother’s elder sister, Mossadeq was the nephew of Mozaffar al-Din Shah Qajar. When his father died in 1892, he was appointed the tax collector of the Khorasan province and was bestowed with the title of "Mossadegh-os-Saltaneh" by Nasser al-Din Shah.[13]

In 1930, Mossadeq married his distant cousin, Zahra Khanum (1879–965), a granddaughter of Nasser al-Din Shah through her mother. The couple had five children, two sons (Ahmad and Ghulam Hussein) and three daughters (Mansura, Zia Ashraf and Khadija).

Education

Mossadeq received his Bachelor of Arts and Masters in (International) Law from University of Paris (Sorbonne) before pursuing higher education in Switzerland. He received his Doctor of Philosophy in 1914 following a Bachelor of Economics in 1916. Mossadeq also taught at the University of Tehran before beginning his political career.[14]

Early political career

Mossadeq started his career in Iranian politics with the Iranian Constitutional Revolution, when at the age of 24, he was elected from Isfahan to the newly inaugurated Persian Parliament, the Majlis of Iran. In 1920, after being self-exiled to Switzerland in protest at the Anglo-Persian Treaty of 1919, he was invited by the new Persian Prime Minister, Hassan Pirnia (Moshir-ed-Dowleh), to become his "Minister of Justice;" but while en route to Tehran, he was asked by the people of Shiraz to become Governor of the "Fars" Province. He was later appointed Finance Minister, in the government of Ahmad Ghavam (Ghavam os-Saltaneh) in 1921, and then Foreign Minister in the government of Moshir-ed-Dowleh in June 1923. He then became Governor of the "Azerbaijan" Province. In 1923, he was re-elected to the Majlis and voted against the selection of the Prime Minister Reza Khan as the new Shah of Persia.

By 1944, Reza Shah Pahlavi had abdicated, and Mosaddeq was once again elected to parliament. This time he took the lead of Jebhe Melli (National Front of Iran), an organization he had founded with nineteen others like Dr.Hossein Fatemi, Ahmad Zirakzadeh, Ali Shayegan, and Karim Sanjabi, aiming to establish democracy and end the foreign presence in Iranian politics, especially by nationalizing the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company’s (AIOC) operations in Iran.

Prime Minister

Support for oil nationalization

Most of Iran’s oil reserves were in the Persian Gulf area and had been developed by the British Anglo-Iranian Oil company and exported to Britain. For a number of reasons—a growing consciousness of how little Iran was getting from the Anglo-Iranian Oil company for its oil; refusal of AIOC to offer of a "50–50 percent profit sharing deal" to Iran as Aramco had to the Saudi Arabian; anger over Iran’s defeat and occupation by the Allied powers—nationalization of oil was an important and popular issue with "a broad cross-section of the Iranian people."[15] In fact, although never formally under colonial rule, the British treated Iran as more or less their own territory and for "much of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century" they attempted to "exploit and control Iran." Ahmed remarks that conspiracy theories concerning the British circulate widely in Iran, where "it is still … believed that if anything goes wrong, if there is any conspiracy afoot, the British are behind it."[16]

General Haj-Ali Razmara, the Shah’s choice, was approved as prime minister June 1950. On March 3, 1951 he appeared before the Majlis in an attempt to persuade the deputies against "full nationalization on the grounds that Iran could not override its international obligations and lacked the capacity to run the oil industry on its own." He was assassinated four days later by Khalil Tahmasebi, a member of the militant fundamentalist group Fadayan-e Islam.[17]

After negotiations for higher oil royalties failed, on March 15 and March 20, 1951, the Iranian Majlis and Senate voted to nationalize the British-owned and operated AIOC, taking control of Iran’s oil industry.

Another force for nationalization was the Tudeh or Communist party. In early April of 1951 the party unleashed nationwide strikes and riots in protest against delays in nationalization of the oil industry along with low wages and bad housing in oil industry. This display of strength, along with public celebration at the assassination of General Razmara made an impact on the deputies of the Majlis.[18]

Election as prime minister

On April 28, 1951, the Majlis named Mosaddeq as new prime minister by a vote of 79–12. Aware of Mosaddeq’s rising popularity and political power, the young Shah Pahlavi appointed Mosaddeq to the Premiership. On May 1, Mosaddeq nationalized the AIOC, cancelling its oil concession due to expire in 1993 and expropriating its assets. The next month a committee of five majlis deputies was sent to Khuzistan to enforce the nationalization.[19]

Mosaddeq explained his nationalization policy in a June 21, 1951 speech:

Our long years of negotiations with foreign countries… have yielded no results this far. With the oil revenues we could meet our entire budget and combat poverty, disease, and backwardness among our people. Another important consideration is that by the elimination of the power of the British company, we would also eliminate corruption and intrigue, by means of which the internal affairs of our country have been influenced. Once this tutelage has ceased, Iran will have achieved its economic and political independence.

The Iranian state prefers to take over the production of petroleum itself. The company should do nothing else but return its property to the rightful owners. The nationalization law provide that 25% of the net profits on oil be set aside to meet all the legitimate claims of the company for compensation…

It has been asserted abroad that Iran intends to expel the foreign oil experts from the country and then shut down oil installations. Not only is this allegation absurd; it is utter invention…[20]

The confrontation between Iran and Britain escalated from there with Mosaddeq’s government refusing to allow the British any involvement in Iran’s oil industry, and Britain making sure Iran could sell no oil. In July, Mossadeq broke off negotiations with AIOC after it threatened "to pull out its employees," and told owners of oil tanker ships that "receipts from the Iranian government would not be accepted on the world market." Two months later the AIOC evacuated its technicians and closed down the oil installations. Under nationalized management many refineries lacked properly the trained technicians that were needed to continue production. The British government announced a de facto blockade and reinforced its naval force in the Gulf and lodged complaints against Iran before the United Nations Security Council.[19]

The British government also threatened legal action against purchasers of oil produced in the formerly British-controlled refineries and obtained an agreement with its sister international oil companies not to fill in where the AIOC was boycotting Iran. The AIOC withdrew its technicians from the refineries and the entire Iranian oil industry came to a "virtual standstill," oil production dropping from 241.4 million barrels in 1950 to 10.6 million in 1952. This "Abadan Crisis" reduced Iran’s oil income to almost nil, putting a severe strain on the implementation of Mossadeq’s promised domestic reforms. At the same time BP and Aramco doubled their production in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Iraq, to make up for lost production in Iran so that no hardship was felt in Britain. The British public rallied behind the cause of AIOC.

Still enormously popular in late 1951, Mosaddeq called elections. His base of support was in urban areas and not in the provinces.[21] According to Ervand Abrahamian: "Realizing that the opposition would take the vast majority of the provincial seats, Mossadeq stopped the voting as soon as 79 deputies—just enough to form a parliamentary quorum—had been elected." National Front members or supporters made up 30 of these 79 deputies. The 17th Majlis convened in February 1952.

According to historian Ervand Abrahamian, tension escalated in the Majlis also. Conservative opponents refused to grant Mosaddeq special powers to deal with the economic crisis caused by the sharp drop in revenue and voiced regional grievances against the capital Tehran, while the National Front waged "a propaganda war against the landed upper class."[21]

Resignation and uprising

On July 16, 1952, during the royal approval of his new cabinet, Mosaddeq insisted on the constitutional prerogative of the prime minister to name a Minister of War and the Chief of Staff, something Shah Pahlavi had done hitherto. The Shah refused, and Mosaddeq announced his resignation appealing directly to the public for support, pronouncing that "in the present situation, the struggle started by the Iranian people cannot be brought to a victorious conclusion."[22]

Veteran politician Ahmad Qavam (also known as Ghavam os-Saltaneh) was appointed as Iran’s new prime minister. On the day of his appointment, he announced his intention to resume negotiations with the British to end the oil dispute, a reversal of Mosaddeq’s policy. The National Front—along with various Nationalist, Islamist, and socialist parties and groups[23]—including Tudeh—responded by calling for protests, strikes and mass demonstrations in favor of Mossadeq. Major strikes broke out in all of Iran’s major towns, with the Bazaar closing down in Tehran. Over 250 demonstrators in Tehran, Hamadan, Ahvaz, Isfahan, and Kermanshah were killed or suffered serious injuries.[24]

After five days of mass demonstrations on Siyeh-i Tir (the 13th of Tir on the Iranian calendar), "military commanders, ordered their troops back to barracks, fearful of overstraining" the enlisted men’s loyalty and left Tehran "in the hands of the protesters."[25] Frightened by the unrest, Shah Pahlavi dismissed Qavam and re-appointed Mosaddeq, granting him the full control of the military he had previously demanded.

Reinstatement and emergency powers

With further rise of his popularity, a greatly strengthened Mosaddeq convinced the parliament to grant him "emergency powers for six months to decree any law he felt necessary for obtaining not only financial solvency, but also electoral, judicial, and educational reforms."[26] Mosaddeq appointed Ayatollah Abol-Ghasem Kashani as house speaker. Kashani’s Islamic scholars, as well as the Tudeh Party, proved to be two of Mosaddeq’s key political allies, although both relationships were often strained.

With his emergency powers, Mosaddeq tried to strengthen the democratically-elected political institutions by limiting the monarchy’s unconstitutional powers,[27] cutting Shah’s personal budget, forbidding him to communicate directly with foreign diplomats, transferring royal lands back to the state, expelling his politically active sister Ashraf Pahlavi.[25]

Mosaddeq's position was also weakened the landed aristocracy, who in abolishing Iran’s centuries-old feudal agriculture sector worked to replace it with a system of collective farming and government land ownership. Although Mosaddeq had previously been opposed to these policies when implemented unilaterally by the Shah, he saw it as a means of checking the power of the Tudeh Party, which had been agitating for general land reform among the peasants.

Overthrow of Mosaddeq

Plot to depose Mosaddeq

The government of the United Kingdom had grown increasingly distressed over Mosaddeq’s policies and were especially bitter over the loss of their control of the Iranian oil industry. Repeated attempts to reach a settlement had failed.

Unable to resolve the issue single-handedly due to its post-World War II problems, Britain looked towards the United States to settle the issue. Initially America had opposed British policies. "After American mediation had failed several times to bring about a settlement," American Secretary of State Dean Acheson "concluded that the British were ‘destructive and determined on a rule or ruin policy in Iran.’"[28] By early 1953, however, there was a new Republican party presidential administration in the United States.

The United States was led to believe by the British that Mosaddeq was increasingly turning towards communism and was moving Iran towards the Soviet sphere at a time of high Cold War fears.[29]

Acting on the opposition to Mosaddeq by the British government and fears that he was, or would become, dependent on the pro-Soviet Tudeh Party at a time of expanding Soviet influence,[30] the United States and Britain began to publicly denounce Mosaddeq’s policies for Iran as harmful to the country.

In the mean time the already precarious alliance between Mosaddeq and Kashani was severed in January 1953, when Kashani opposed Mosaddeq’s demand that his increased powers be extended for a period of one year.

Operation Ajax

In October 1952, Mosaddeq declared that Britain was "an enemy," and cut all diplomatic relations with the United Kingdom. In November and December 1952, British intelligence officials suggested to American intelligence that the prime minister should be ousted. The new U.S. administration under Dwight D. Eisenhower and the British government under Winston Churchill agreed to work together toward Mosaddeq’s removal. In March 1953, Secretary of State John Foster Dulles directed the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), which was headed by his younger brother Allen Dulles, to draft plans to overthrow Mosaddeq.[31]

On April 4, 1953, CIA director Dulles approved US$1 million to be used "in any way that would bring about the fall of Mosaddeq." Soon the CIA’s Tehran station started to launch a propaganda campaign against Mosaddeq. Finally, according to The New York Times, in early June, American and British intelligence officials met again, this time in Beirut, and put the finishing touches on the strategy. Soon afterward, according to his later published accounts, the chief of the CIA’s Near East and Africa division, Kermit Roosevelt, Jr., the grandson of U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt, arrived in Tehran to direct it.[32] In 2000, The New York Times made partial publication of a leaked CIA document titled, "Clandestine Service History—Overthrow of Premier Mosaddeq of Iran—November 1952-August 1953." This document describes the planning and execution conducted by the American and British governments. The New York Times published this critical document with the names censored. The New York Times also limited its publication to scanned image (bitmap) format, rather than machine-readable text. This document was eventually published properly – in text form, and fully unexpurgated. The complete CIA document is now web published. The word "blowback" appeared for the very first time in this document.

The plot, known as Operation Ajax, centered around convincing Iran’s monarch to use his constitutional authority to dismiss Mosaddeq from office, as he had attempted some months earlier. But Shah Pahlavi was uncooperative, and it would take much persuasion and many meetings to successfully execute the plan.

Mosaddeq became aware of the plots against him and grew increasingly wary of conspirators acting within his government. Soon Pro-Mosaddeq supporters, both socialists and nationalists, threatened Muslim leaders with "savage punishment if they opposed Mosaddeq," with impression that Mosaddeq was cracking down on dissent, and stirring anti-Mosaddeq sentiments within the religious community. Mosaddeq then moved to dissolve parliament, in spite of the Constitutional provision which gave the Shah sole authority to dissolve Parliament. After taking the additional step of abolishing the Constitutional guarantee of a “secret ballot,” Mosaddeq’s victory in the national plebiscite was assured. The electorate was forced into a non-secret ballot and Mosaddeq won 99.93 percent of the vote. The tactics employed by Mosaddeq to remain in power appeared dictatorial in their result, playing into the hands of those who wished to see him removed. Parliament was suspended indefinitely, and Mosaddeq’s emergency powers were extended.

Shah’s exile

In August 1953, Mosaddeq attempted to convince the Shah to leave the country and allow him control over the government. The Shah refused, and formally dismissed the Prime Minister. Mosaddeq refused to leave, however, and when it became apparent that he was going to fight to overthrow the monarchy, the Shah, as a precautionary measure, flew to Baghdad and from there to Rome, Italy, after signing two decrees, one dismissing Mosaddeq and the other nominating General Fazlollah Zahedi Prime Minister.

Coup d'etat

Once again, massive protests broke out across the nation. Anti- and pro-monarchy protesters violently clashed in the streets, leaving almost 300 dead. The pro-monarchy forces, led by retired army General and former Minister of Interior in Mosaddeq’s cabinet, Fazlollah Zahedi and street thugs like Shaban Jafari (also known as Shaban "the Brainless"),[33] gained the upper hand on August 19, 1953 (28 Mordad). The military intervened as the pro-Shah tank regiments stormed the capital and bombarded the prime minister’s official residence. Mosaddeq managed to flee from the mob that set in to ransack his house, and, the following day, surrendered to General Zahedi, who had meanwhile established his makeshift headquarters at the Officers' Club. Mosaddeq was arrested at the Officers' Club and transferred to a military jail shortly after.

Shah’s return

Shortly after the return of the Shah, on August 22, 1953, from the brief self-imposed exile in Rome, Mosaddeq was tried by a military tribunal for high treason. Zahedi and Shah Pahlavi were inclined, however, to spare the man’s life (the death penalty would have applied according to the laws of the day). Mosaddeq received a sentence of 3 years in solitary confinement at a military jail and was exiled to his village not far from Tehran, where he remained under house arrest on his estate until his death, on March 5, 1967.[34]

Zahedi’s new government soon reached an agreement with foreign oil companies to form a "Consortium" and "restore the flow of Iranian oil to world markets in substantial quantities."[35]

Legacy

Iran

The overthrow of Mossadeq served as a rallying point in anti-US protests during the 1979 Iranian revolution and to this day is said to be one of the most popular figures in Iranian history.[36] Ahmed remarks that as a result of US involvement in his overthrow, "Americans were seen as propping up the Shah and supporting tyranny." Iran's subsequent hostility towards the U.S., characterized by Ruholla Khomeini as the "great Satan" owes much to this perception. [37] Despite this he is generally ignored by the government of the Islamic Republic because of his secularism and western manners.

The withdrawal of support for Mossadeq by the powerful Shia clergy’s has been regarded as having been motivated by their fear of the "chaos" of "a communist takeover."[8] Some argue that while many elements of Mossadeq’s coalition abandoned him it was the loss of support from Ayatollah Abol-Ghasem Kashani and other clergy that was fatal to his cause, reflective of the dominance of the Ulema in Iranian society and a portent of the Islamic Revolution to come. "The loss of the political clerics effectively cut Mossadeq’s connections with the lower middle classes and the Iranian masses which are crucial to any popular movement" in Iran.[38]

U.S. and other countries

The extent of the U.S. role in Mossadeq’s overthrow was not formally acknowledged for many years, although the Eisenhower administration was quite vocal in its opposition to the policies of the ousted Iranian Prime Minister. In his memoirs, Eisenhower writes angrily about Mossadeq, and describes him as impractical and naive, though he stops short of admitting any overt involvement in the coup.

Eventually the CIA’s role became well-known, and caused controversy within the organization itself, and within the CIA congressional hearings of the 1970s. CIA supporters maintain that the plot against Mosaddeq was strategically necessary, and praise the efficiency of agents in carrying out the plan. Critics say the scheme was paranoid and colonial, as well as immoral.

In March 2000, then-Secretary of State Madeleine Albright stated her regret that Mosaddeq was ousted: "The Eisenhower administration believed its actions were justified for strategic reasons. But the coup was clearly a setback for Iran’s political development and it is easy to see now why many Iranians continue to resent this intervention by America." In the same year, the New York Times published a detailed report about the coup based on alleged CIA documents.[4]

The US public and government had been very pro-Mosaddeq until the election of Dwight Eisenhower. Eisenhower’s trust in Britain and Cold War fears made it very easy to convince him of Iran’s communist problem. Even after the coup, as Ahmed points out, despite the change in official policy "many Americans criticized the Shah and advocated genuine democracy."[39]

For his sudden rise in popularity inside and outside of Iran, and for his defiance of the British, Mosaddeq was named as Time Magazine’s 1951 Man of the Year. Other notables considered for the title that year included Dean Acheson, President Dwight D. Eisenhower and General Douglas MacArthur.[40]

In early 2004, the Egyptian government changed a street name in Cairo from Pahlavi to Mosaddeq, to facilitate closer relations with Iran.

He was good friends with Mohammad Mokri until his death.

| Preceded by: Hossein Ala' |

Prime Minister of Iran 1951 – July 16, 1952 |

Succeeded by: Ghavam os-Saltaneh |

| Preceded by: Ghavam os-Saltaneh |

Prime Minister of Iran July 21, 1952 – August 19, 1953 |

Succeeded by: Fazlollah Zahedi |

Notes

- ↑ Mike Thomson, A Very British Coup, BBC Radio 4. Retrieved July 11, 2008.

- ↑ The Independent, Leading Article: A counter-productive policy towards Iran. Retrieved July 11, 2008.

- ↑ John Coert Campbell and Arleen Keylin, The Middle East (New York, NY: New York Times, 1976, ISBN 9780405066603), 205.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 James Risen, Secrets of History: The C.I.A. in Iran, The New York Times. Retrieved July 11, 2008.

- ↑ Dan deLuce, The Spectre of Operation Ajax, The Guardian. Retrieved July 11, 2008.

- ↑ Mark J. Gasiorowski and Malcolm Byrne, Mohammad Mosaddeq and the 1953 Coup in Iran, National Security Archive, USA. Retrieved July 11, 2008.

- ↑ Hertz (2003), 88.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Nasr (2006), 124.

- ↑ Jonathan Schanzer, Review of All the Shah’s Men by Stephen Kinzer, Middle East Quarterly. Retrieved July 11, 2008.

- ↑ Mackay (1996), 203, 4.

- ↑ Keddie (1981), 140.

- ↑ Ahmed (2002), 141.

- ↑ The Telegraph, Key figures: Mohammad Mossadegh 1882-1967. Retrieved July 11, 2008.

- ↑ Bahman Maghsoudlou, The Political Life and Legacy of Mosaddeq, International Film and Video Center. Retrieved July 11, 2008.

- ↑ Saikal (1980), 38.

- ↑ Ahmed (2002), 107.

- ↑ Saikal (1980), 38–9.

- ↑ Abrahamian (1982), 266.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Abrahamian (1982), 268.

- ↑ Mustafa Fateh, Panjah Sal-e Naft-e Iran (Tehran: Intishārāt-i Payām, 1979), 525.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Abrahamian (1982), 268–70.

- ↑ Abrahamian (1982), 270–1.

- ↑ Gholamreza Nejati, Mossadegh: The Years of Struggle and Opposition (Tehran, IR, 1998, ISBN 9789643172831), 761.

- ↑ Abrahamian (1982), 271.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Abrahamian (1982), 272.

- ↑ Abrahamian (1982), 273.

- ↑ Sepehr Zabih, The Mossadegh Era: Roots of the Iranian Revolution (Chicago, IL: Lake View Press, 1982, ISBN 9780941702010), 65.

- ↑ Saikal 91980), 42.

- ↑ Gasiorowski and Byrne (2004), 125.

- ↑ Schanzer (2004).

- ↑ Malcolm Byrne, The Secret CIA History of the Iran Coup, 1953, George Washington University, quoting National security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 28. Retrieved July 11, 2008.

- ↑ David Halberstam, The Fifties (New York, NY: Ballentine Books, 1993, ISBN 0449909336), 366-367.

- ↑ Pahlavani, Misinformation, Misconceptions and Misrepresentations. Retrieved July 11, 2008.

- ↑ Webshots.com, Photograph of the graveside of Mohammad Masaddeq. Retrieved July 11, 2008.

- ↑ New Yor Times, Statements on Iran Oil Accord. Retrieved July 11, 2008.

- ↑ Hertz (2003), 88.

- ↑ Ahmed. 2002. page 108.

- ↑ Mackay (1996), 203, 4.

- ↑ Ahmed (2002), 108.

- ↑ Time, Mohammed Mossadegh, Man of the Year. Retrieved July 8, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Abrahamian, Ervand. 1982. Iran Between Two Revolutions. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691053424.

- Abrahamian, Ervand. 1993. Khomeinism: Essays on the Islamic Republic. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0520081730.

- Ahmed, Akbar. 2002. Islam Today. London, UK: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 1860642578.

- Diba, Farhad. 1986. Dr. Mohammad Mossadegh; A Political Biography. London, UK: Croom Helm. ISBN 0709945175.

- Elm, Mostafa. 1994. Oil, Power, and Principle: Iran’s Oil Nationalization and Its Aftermath. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 0-8156-2642-8.

- Gasiorowski, Mark J. 1987. The 1953 Coup D'Etat in Iran. International Journal of Middle East Studies. 19 (3): 261–86.

- Gasiorowski, Mark J. 1991. U.S. Foreign Policy and the Shah: Building a Client State in Iran. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0801424127.

- Gasiorowski, Mark J. and Malcolm Byrne. 2004. Mohammad Mosaddeq and the 1953 coup in Iran. Modern intellectual and political history of the Middle East. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780815630180.

- Heiss, Mary Ann. 1997. Empire and Nationhood: The United States, Great Britain, and Iranian Oil, 1950-1954. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231108192.

- Hertz, Noreena. 2003. The Silent Takeover: Global Capitalism and the Death of Democracy. New York, NY: HarperCollins. ISBN 006055973X.

- Farman-Farmaian, Sattareh with Dona Munker. 2006. Daughter of Persia: A Woman’s Journey from Her Father’s Harem Through the Islamic Revolution. New York, NY: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 0307339742.

- Katouzian, Homa. 1991. Musaddiq and the Struggle for Power in Iran. London, UK: I.B. Tauris & Co. ISBN 1850432104.

- Keddie, Nikki R. 2003. Modern Iran: Roots and Results of Revolution. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300098561.

- Keddie, Nikki R. and Richard, Yann. 1981. Roots of Revolution. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300026061.

- Kinzer, Stephen. 2003. All the Shah’s Men|All The Shah’s Men: An American Coup and the Roots of Middle East Terror. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0471265179.

- Kinzer, Stephen. 2006. Overthrow: America’s Century of Regime Change from Hawaii to Iraq. New York, NY: Times Books. ISBN 0805078614.

- Nasr, Seyyed Vali Reza. 2006. The Shia Revival: How Conflicts Within Islam will Shape the Future. New York, NY: Norton. ISBN 9780393062113.

- Mackey, Sandra. 1996. The Iranians: Persia, Islam, and the Soul of a Nation. New York, NY: Dutton. ISBN 9780525940050.

- Saikal, Amin. 1980. The Rise and Fall of the Shah. London, UK: Angus & Robertson. ISBN 9780207144127.

External links

All links retrieved November 9, 2022.

- The Mossadegh Project—Site containing pictures, media and biography of Mosaddeq.

- James Risen: Secrets of History: The C.I.A. in Iran—A special report; How a Plot Convulsed Iran in ’53 (and in ’79). The New York Times, 16 April 2000.

- New York Times Archive containing declassified US intelligence Documents on the Coup of 1953.

- A short account of 1953 Coup in Iran.

| ||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.