Noh

Noh or Nō (Japanese: 能) is the oldest surviving form of classical Japanese musical drama. It has been performed since the fourteenth century. Together with the closely-related kyogen farce, it evolved from various popular, folk and aristocratic art forms, including Chinese acrobatics, dengaku, and sarugaku and was performed at temples and shrines as part of religious ceremonies. During the second half of the fourteenth century, Noh was established in its present form by Kan'ami and his son Zeami Motokiyo, under the patronage of the Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu.

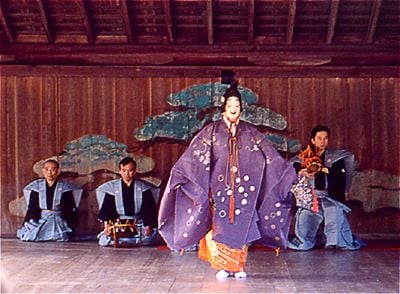

Noh dramas are highly choreographed and stylized, and include poetry, chanting and slow, elegant dances accompanied by flute and drum music. The stage is almost bare, and the actors use props and wear elaborate costumes. The main character sometimes wears a Noh mask. Noh plays are taken from the literature and history of the Heian period and are intended to illustrate the principles of Buddhism.

History

Noh is the earliest surviving form of Japanese drama. Noh theater grew out of a combination of sarugaku, a type of entertainment involving juggling, mime, and acrobatics set to drums and associated with Shinto rituals; dengaku (harvest dances); Chinese-style dances; and traditional chanted ballads and recitations. Performances were sponsored by shrines and temples and were intended to illustrate religious teachings as well as to entertain. By the middle of the fourteenth century, Noh had evolved into the form in which it is known today.

In 1375 at Kasuge Temple, 17-year-old Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, a powerful shogun, witnessed a Noh performance by Kan’ami Kiyotsugu and his twelve-year-old son Zeami Motokiyo. He took a passionate interest in Noh, and under his patronage it developed into a highly refined and elegant form of drama. Zeami (1363–1443) wrote approximately one hundred plays, some of which may have originated with his father Kanami (1333–1385), and also a manual for Noh actors, published in 1423 and still used today by young performers. Zeami wrote in the upper-class language of the fourteenth century, but drew most of his subject material from the people, events and literature of the Heian period (794–1185), which was considered a sort of “Golden Age.” Many of Zeami’s plays are performed today, including Takasago and The Well Curb. The shogun also elevated the social status of Noh actors, and in an effort to restrict Noh to the aristocracy, commoners were forbidden to learn the music and dances.

During the Muromachi period (1339–1573) the repertoire of Noh expanded to more than one thousand plays. Originally a stage was constructed for each performance at a temple or shrine; by the end of the Muromachi period separate Noh theaters were being built. From 1467 to 1568, civil war prevented the shogunate from involving itself in cultural pursuits, but the popularity of tea ceremony and art forms such as Noh spread through the samurai class to all levels of society. With the return of peace, the shogunate once again took an interest in Noh, and both Hideyoshi and later Ieyasu Tokugawa included Noh performances in their coronation festivities. In 1647, the shogun Ieyasu Tokugawa decreed that no variations to Noh plays would be permitted. Near the end of the Edo period (1600–1868), as the status of the samurai class declined, Noh became increasingly popular with the middle and lower classes. Government sponsorship of Noh ended with the Meiji reforms (1868–1912), but it continued to flourish under the private patronage of the nobility.

Kyogen

During intervals or between Noh plays, there is a half-hour kyogen performance. Kyogen is an elaborate art form in itself, derived from various traditions including sarugaku, kusemai (mime performed by Buddhist monks while reciting poetry), kagura (Shinto fan dances used to invoke the presence of God), eunen (dances performed by Buddhist priests at festivals), dengaku (harvest dances), bugaku (Imperial court dances from the twelfth century) and furyu (popular songs and dances of the fourteenth century, performed at intervals to ward off pestilence or achieve salvation). A kyogen may reinforce or explain the moral of the Noh play, or it may offer nonsensical comic relief.

Kyogen usually involves two characters on the stage, a shite and an ado (supporter). They can also be Taro Kajya and the Jiro Kajya, young male servants to royalty.

Stage

The Noh play takes place on a sparse stage made out of hinoki (Japanese cypress wood), and has four basic parts, hombutai (main stage), hashigakari (corridor), atoza (back stage) and giutaiza (side stage). The pillars built on each corner of the stage support the roof. The stage is bare with the exception of the kagami-ita, a painting of a pine tree at the back of the stage. There are many explanations for this tree, one of the more common being that it symbolizes a means by which deities were said to descend to earth in Shinto ritual.

Another unique feature of the stage is the hashigakari, the narrow bridge to the left of the stage that the principal actors use to enter the stage. There is a row of plants around the stage and along the hashigakari are three pine trees, representing positions at which an actor may stop and declaim while making an entrance to the main stage. The trees and plants are carried over from the early period when stages were constructed outdoors on the grounds of temples and shrines. Today most Noh plays are performed on indoor stages. There is still a tradition of illuminating the plays with bonfires when they are performed in the open at night.

Plays

Noh has a current repertoire of approximately 250 plays, which can be organized into five categories: plays about God, plays about warriors, plays about women, plays about miscellaneous characters (such as madwomen or figures from history and literature) and plays about demons. A Noh program usually includes one play from each category, in that order.

A Noh play portrays one emotion, such as jealousy, rage, regret or sorrow, which dominates the main character, the shite. All elements of the play (recitation, dialogue, poetry, gestures, dance and musical accompaniment) work together to build this emotion to a climax at the end of the play. Many plays depict the return of a historical figure, in a spiritual or ghostly form, to the site where some significant event took place during his life. Buddhists during the fourteenth century believed that a person who had died was tied to this earthly life as long as he continued to possess a strong emotion or desire, and that it was necessary to relive the scene in order to obtain “release.” During a Noh performance, the characters’ personalities are less important than the emotion being portrayed. This is conveyed through stylized movements and poses.

The progress of the play can be ascertained by the positions of the two main actors on the stage. The stage has almost no scenery, but actors use props, especially chukei (folding fans) to represent objects such as swords, pipes, walking sticks, bottles and letters. The main character wears an elaborate costume consisting of at least five layers, and sometimes a mask. He arrives on stage after all the other characters, appearing from the hashigakari, or bridge, behind the main stage.

Each actor occupies a designated position on the stage. A chorus of six to eight people sits to one side and echoes the characters’ words, or even speaks for them during a dance or other movement. Four musicians sit behind a screen to the back of the stage; the four instruments used in Noh theater are the transverse flute (nohkan), hip-drum (okawa or otsuzumi), the shoulder-drum (kotsuzumi), and the stick-drum (taiko).

Roles

There are four major categories of Noh performers: shite, or primary actor; waki, a counterpart or foil to the shite; kyōgen, who perform the aikyogen interludes during the play; and hayashi, the musicians. There are also the tsure, companions to the shite; the jiutai, a chorus usually composed of six to eight actors; and the koken, two or three actors who are stage assistants. A typical Noh play will involve all these categories of actors and usually lasts anywhere from thirty minutes to two hours.

The waki are usually one or two priests attired in long, dark robes, and play the role of observers and commentators on behalf of the audience. A play usually opens with a waki who enters and describes the scene to the audience; all the scenes are actual places in Japan. The shite (main character) may then enter, dressed as local person, and explain the significance of the site to the waki. The shite then leaves and returns fully costumed in elaborate robes, with or without a mask.

Dancing

Dances are an important element of many Noh plays. The dances are slow, and the style varies according to the subject matter of the play. They are usually solos lasting for several minutes. The ideal technique is to carry out the dance so perfectly that the audience is unaware that any effort is being made. Noh dancing is meant to be smooth and free flowing, like writing with a brush. The dancer performs a variety of kata, or movements, the most important of which is walking by sliding the foot forward, pivoting it up and then down on the heel. The highest compliment that can be paid to a Noh dancer is that his walking is good. Other movements include viewing a scene, riding a horse, holding a shield, weeping, or stamping. When a play contains the stamping movement, large clay pots are placed under the floor to enhance the acoustics. One movement is to “dance without moving.” The rhythm of movement is extremely important; the rhythm should grow and then fade like a flower blooming and withering. Some movements are so subtle that they cannot be taught; although dancers begin training in childhood, they are said to achieve their best performance in middle age.

Dramatic Material

Okina (or Kamiuta) is a unique play that combines dance with Shinto ritual. It is considered the oldest type of Noh play, and is probably the most often performed. It will generally be the opening work at any program or festival.

The Tale of the Heike, a medieval tale of the rise and fall of the Taira clan, originally sung by blind monks who accompanied themselves on the biwa, is an important source of material for Noh (and later dramatic forms), particularly for warrior plays. Another major source is The Tale of Genji, an eleventh-century work about the romantic entanglements of an emperor’s illegitimate son. Authors also drew on Nara and Heian period Japanese classics, and on Chinese sources. The most popular play in the Noh repertoire is Lady Aoi (Aoi no Ue), which is based on events from the Tale of Genji.

Aesthetics

According to Zeami, all Noh plays should create an aesthetic ideal called yugen (“that which lies below the surface”), meaning subtle and profound spirit, and hana, meaning novelty. Noh truly represents the Japanese cultural tradition of finding beauty in subtlety and formality. The text of Noh dramas is full of poetical allusions, and the dances are slow and extremely elegant. The starkness of the bare stage contrasts with the rich beauty of the costumes and reflects the austere Buddhist lifestyle adopted by the aristocracy during the fourteenth century. The strict choreography, in which every detail is prescribed by tradition, is typical of many Buddhist art forms in which the essential meaning of a work of art never changes, and the audience gains a profound understanding by reflecting on it repeatedly. The Noh plays were intended to make the audience reflect on the transitoriness of earthly life and the importance of cultivating one’s spirit.

The aesthetics of Noh drama anticipate many developments of contemporary theater, such as a bare stage, the symbolic use of props, stylized movement, and the presence of commentators or stage-hands on the stage.

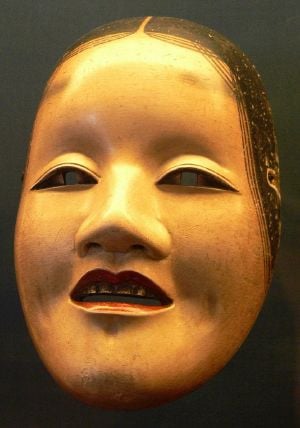

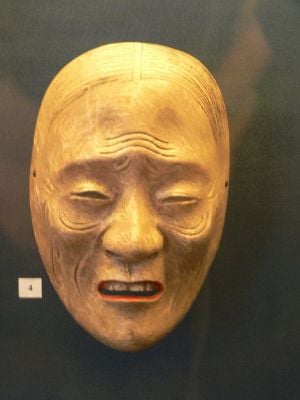

Masks in Noh plays

The masks in Noh (能面, nō-men, or 面, omote) all have names.

Usually only the shite, the main character, wears a mask. However, in some cases, the tsure may also wear a mask, particularly for female roles. Noh masks are used to portray females, youngsters, old men or nonhuman (divine, demonic, or animal) characters. A Noh actor who wears no mask plays a role of an adult man in his twenties, thirties, or forties. The side player, waki, wears no mask.

Noh masks cover only the front of the face and have small holes for the eyes, nostrils and mouth. They are lightweight, made of cypress wood, covered with gesso and glue, sanded down and painted with the prescribed colors for that character. Hair and the outlines of the eyes are traced with black ink. The facial expression of the masks is neutral. Before putting on the mask, the actor gazes at it for a long time to absorb its essence. When he dons the mask, the actor’s personality disappears and he becomes the emotion portrayed by the mask.

When used by a skilled actor, Noh masks have the ability to depict different emotional expressions according to head pose and lighting. An inanimate mask can have the appearance of being happy, sad, or a variety of subtle expressions. Many of the masks in use today are hundreds of years old. Noh masks are prized for their beauty and artistry.

Actors

There are about 1,500 professional Noh actors in Japan today, and the art form continues to thrive. The five extant schools of Noh acting are the Kanze (観世), Hōshō (宝生), Komparu (金春), Kita (喜多), and Kongō (金剛) schools. Each school has a leading family (iemoto) known as Sōke, whose leader is entitled to create new plays or edit existing songs. The society of Noh actors retains characteristics of the feudal age, and strictly protects the traditions passed down from their ancestors. Noh drama exists today in a form almost unchanged since the fourteenth century. Every movement in a Noh play is choreographed and usually conveys a symbolic meaning essential to the story. There is no improvisation or individual interpretation by the actors in a Noh play.

Traditionally all the actors in a Noh play were male. Recently Izumi Junko became the first female Noh performer, and also played the lead in a movie, Onmyouji, set in the Heian period.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brazell, Karen. Traditional Japanese Theater. Columbia University Press.

- Chappell, Wallace (foreword), J. Thomas Rimer (trans.); Yamazaki Masakazu (trans.). On the Art of the Noh Drama: The Major Treatises of Zeami (Princeton Library of Asian Translations). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1983.

- Pound, Ezra and Ernest Fenollosa. The No Theatre of Japan: With Complete Texts of 15 Classic Plays. Dover Publications, 2004.

- Pound, Ezra. Classic Noh Theatre of Japan (New Directions Paperbook). New Directions Publishing Corporation; 2nd revised edition, 1979.

- Waley, Arthur. The No Plays of Japan: An Anthology. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. Unabridged edition, 1998.

External links

All links retrieved November 15, 2022.

- Noh mask master Shigeharu Nagasawa Noh Masks in Japanese.

- Noh Theatre Japan Zone

- Japanese Noh Theater Artelino

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.