Numbat

| Numbat[1] |

|---|

|

| Scientific classification |

|

|

| Myrmecobius fasciatus Waterhouse, 1836 |

Numbat range

(green — native, pink — reintroduced) |

|

Numbat is the common name for members of the marsupial species Myrmecobius fasciatus, a diurnal, termite-eating mammal characterized by a slender body with white stripes, narrow pointed snout, small mouth with numerous small teeth, and a long, sticky tongue. Also known as the banded anteater and walpurti, M. fasciatus is found in Western Australia. It is the only extant member of its family, Myrmecobiidae.

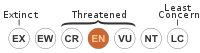

Numbats provide important ecological values as predators specialized on termites, while being preyed upon by carpet pythons, red foxes, eagles, hawks, and falcons. Their unique appearance, combined with their diurnal habits, also add to the beauty of nature for humans and the numbat serves as the emblem of Western Australia. Despite these values, the species, which was once widespread in Australia, is now an endangered species, restricted to several small colonies.

Physical description

As a marsupial, the numbat is a non-placental mammal. However, unlike most marsupials in which the females typically have an external pouch where the newborn are nursed, numbat females have no pouch. The four mammae (milk-secreating teats) are protected, however, by a patch of crimped, golden hair and by the swelling of the surrounding abdomen and thighs during lactation (Cooper 2011).

The numbat is relatively small compared to many termite-consuming mammals, with a body length of about 17.5 to 27.5 centimeters (7-11 inches) and a tail of about 13.0 to 17 centimeters (5-6.7 inches), or roughly 30 to 45 centimeters (12-17.7 inches) in total length. The adult numbat weighs from about 280 to 550 grams (0.6-1.2 pounds) (Ellis 2003).

The numbat has a finely pointed muzzle, a small mouth, and small, round-tipped ears. There are five toes on the stout forefeet, and four toes on the hindfeet; all four feet have thick and large claws (Cooper 2011; Ellis 2003). The tail is prominent and bushy. Like many termite-eating animals, the numbat has an unusually long, narrow, tongue, coated with sticky saliva produced by large submandibular glands. The tongue can reach 10 centimeters from the mouth opening (Ellis 2003). A further adaptation to the diet is the presence of numerous ridges along the soft palate, which apparently help to scrape termites off the tongue so that they can be swallowed.

Like other mammals that eat termites or ants, the numbat has a degenerate jaw with up to 50 very small non-functional teeth, and although it is able to chew (Cooper 2011), it rarely does so, because of the soft nature of its diet. Uniquely among terrestrial mammals, there is an additional cheek tooth between the premolars and molars; it is unclear whether this represents a supernumary molar tooth or a deciduous tooth retained into adult life. As a result, although not all individuals have the same dental formula, in general, it follows the unique pattern (Cooper 2011):

The numbat is a distinctive and colorful creature, with thick and short hair. The color varies considerably, from soft gray to reddish-brown, often with an area of brick red on the upper back, and always with a conspicuous black stripe running from the tip of the muzzle through the eyes to the bases of the ears. There are between four and eleven white stripes across the animal's hindquarters, which gradually become fainter towards the mid-back. The underside is cream or light gray, while the tail is covered with long gray hair flecked with white (Cooper 2011; Ellis 2003)

The numbat's digestive system is relatively simple, and lacks many of the adaptations found in other entomophagous animals, presumably because termites are easier to digest than ants, having a softer exoskeleton. Numbats are apparently able to gain a considerable amount of water from their diet, since their kidneys lack the usual specializations for retaining water found in other animals living in their arid environment (Cooper and Withers 2010). Numbats also possess a sternal scent gland, which may be used for marking its territory (Cooper 2011).

Although the numbat finds termite mounds primarily using scent, it has the highest visual acuity of any marsupial, and, unusually for marsupials, has a high proportion of cone cells in the retina. These are both likely adaptations for its diurnal habits, and vision does appear to be the primary sense used to detect potential predators (Cooper 2011). Numbats regularly enter a state of torpor, which may last up to fifteen hours a day during the winter months (Cooper and Withers 2004).

Distribution and habitat

Numbats were formerly found across southern Australia from Western Australia across as far as northwestern New South Wales. However, the range has declined significantly since the arrival of Europeans, and the species has survived only in several remnant populations in two small patches of land in the Dryandra Woodland and the Perup Nature Reserve, both in Western Australia. In recent years, it has, however, been successfully reintroduced into a few fenced reserves, including some in South Australia (Yookamurra Sanctuary) and New South Wales (Scotia Sanctuary) (Friend and Burbidge 2008)

Today, numbats are found only in areas of eucalypt forest, but they were once more widespread in other types of semi-arid woodland, Spinifex grassland, and even in terrain dominated by sand dunes (Cooper 2011).

Behavior, feeding, reproduction, and life cycle

Unlike most other marsupials, the numbat is diurnal; the numbat is the only marsupial that is fully active by day.

Numbats are insectivores and eat a specialized diet almost exclusively of termites. An adult numbat requires up to 20,000 termites each day. Despite its banded anteater name, although the remains of ants have occasionally been found in numbat dung, these belong to species that themselves prey on termites, and so were presumably eaten accidentally, along with the main food (Cooper 2011).

The diurnal habit of the numbat is related to it method of feeding. While the numbat has relatively powerful claws for its size (Lee 1984), it is not strong enough to get at termites inside their concrete-like mound, and so must wait until the termites are active. It uses a well-developed sense of smell to locate the shallow and unfortified underground galleries that termites construct between the nest and their feeding sites; these are usually only a short distance below the surface of the soil, and vulnerable to the numbat's digging claws. The numbat digs up termites from loose earth with its front claws and captures them with its long sticky tongue.

The numbat synchronizes its day with termite activity, which is temperature dependent: in winter, it feeds from mid-morning to mid-afternoon; in summer, it rises earlier, takes shelter during the heat of the day, and feeds again in the late afternoon.

At night, the numbat retreats to a nest, which can be in a hollow log or tree, or in a burrow, typically a narrow shaft 1-2 meters long, which terminates in a spherical chamber lined with soft plant material: grass, leaves, flowers, and shredded bark. The numbat is able to block the opening of its nest, with the thick hide of its rump, to prevent a predator being able to access the burrow.

Known predators on numbats include carpet pythons, introduced red foxes, and various falcons, hawks, and eagles, including the little eagle, brown goshawk, and collared sparrowhawk. Numbats have relatively few vocalizations, but have been reported to hiss, growl, or make a repetitive 'tut' sound when disturbed (Cooper 2011).

Adult numbats are solitary and territorial; an individual male or female establishes a territory of up to 1.5 square kilometers (370 acres) (Lee 1984) early in life, and defends it from others of the same sex. The animal generally remains within that territory from that time on; male and female territories overlap, and in the breeding season males will venture outside their normal home range to find mates.

Numbats breed in February and March, normally producing one litter a year, although they can produce a second if the first is lost (Power et al. 2009). Gestation lasts 15 days, and results in the birth of four young.

The young are 2 centimeters (0.79 in} long at birth, and crawl to the teats, and remain attached until late July or early August, by which time they have grown to 7.5 cm (3.0 in). They first develop fur at 3 cm (1.2 in), and the adult coat pattern begins to appear once they reach 5.5 cm (2.2 in). After weaning, the young are initially left in a nest, or carried about on the mother's back, and they are fully independent by November. Females are sexually mature by the following summer, but males do not reach maturity for another year (Cooper 2011).

Classification

The numbat genus Myrmecobius is the sole extant member of the family Myrmecobiidae; one of the three families that make up the order Dasyuromorphia, the Australian marsupial carnivores (Wilson and Reeder 2005). The order Dasyuromorphia comprises most of the Australian carnivorous marsupials, including quolls, dunnarts, the Tasmanian devil, and the recently extinct thylacine.

The species is not closely related to other extant marsupials; the current arrangement in the dasyuromorphia order places its monotypic family with the diverse and carnivorous species of Dasyuridae. A closer affinity with the extinct thylacine has been proposed. Genetic studies have shown that the ancestors of the numbat diverged from other marsupials between 32 and 42 million years ago, during the late Eocene (Bininda-Emonds 2007).

Only a very small number of fossil specimens are known, the oldest dating back to the Pleistocene, and no fossils belonging to other species from the same family have yet been discovered (Cooper 2011).

There are two recognized subspecies. However, one of these, the rusty numbat (M. f. rufus), has been extinct since at least the 1960s, and only the nominate subspecies (M. f. fasciatus) remains alive today. As its name implies, the rusty numbat was said to have a more reddish coat than the surviving subspecies (Cooper 2011).

Conservation status

Until European colonization, the numbat was found across most of the area from the New South Wales and Victorian borders west to the Indian Ocean, and as far north as the southwest corner of the Northern Territory. It was at home in a wide range of woodland and semi-arid habitats. The deliberate release of the European red fox in the 19th century, however, wiped out the entire numbat population in Victoria, NSW, South Australia and the Northern Territory, and almost all numbats in Western Australia as well. By the late 1970s, the population was well under 1,000 individuals, concentrated in two small areas not far from Perth, Dryandra, and Perup.

The first record of the species described it as beautiful (Moore 1884); its appeal saw it selected as the faunal emblem of the state of Western Australia and initiated efforts to conserve it from extinction.

It appears that the reason the two small Western Australia populations were able to survive is that both areas have many hollow logs that may serve as refuge from predators. Being diurnal, the numbat is much more vulnerable to predation than most other marsupials of a similar size. When the Western Australia government instituted an experimental program of fox baiting at Dryandra (one of the two remaining sites), numbat sightings increased by a factor of 40.

An intensive research and conservation program since 1980 has succeeded in increasing the numbat population substantially, and reintroductions to fox-free areas have begun. Perth Zoo is very closely involved in breeding this native species in captivity for release into the wild. Despite the encouraging degree of success so far, the numbat remains at considerable risk of extinction and is classified as an endangered species (Friend and Burbidge 2008).

Discovery

The numbat first became known to Europeans in 1831. It was discovered by an exploration party who were exploring the Avon Valley under the leadership of Robert Dale. George Fletcher Moore, who was a member of the expedition, recounted the discovery thus (Moore 1884):

"Saw a beautiful animal; but, as it escaped into the hollow of a tree, could not ascertain whether it was a species of squirrel, weasel, or wild cat..."

and the following day

"chased another little animal, such as had escaped from us yesterday, into a hollow tree, where we captured it; from the length of its tongue, and other circumstances, we conjecture that it is an ant-eater—its colour yellowish, barred with black and white streaks across the hinder part of the back; its length about twelve inches."

The first classification of specimens was published by George Robert Waterhouse, describing the species in 1836 and the family in 1841. Myrmecobius fasciatus was included in the first part of John Gould's The Mammals of Australia, issued in 1845, with a plate by H. C. Richter illustrating the species.

Footnotes

- ↑ (2005) Mammal Species of the World, 3rd, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2 vols. (2142 pp.). ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Friend, T. & Burbidge, A. (2008). Myrmecobius fasciatus. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Downloaded on 08 October 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bininda-Emonds, O. R. P. 2007. The delayed rise of present-day mammals. Nature 446: 507–512. PMID 17392779.

- Cooper, C. E. 2011. Myrmecobius fasciatus (Dasyuromorphia: Myrmecobiidae). Mammalian Species 43(1): 129–140.

- Cooper, C. E., and P. C. Withers. 2004. Patterns of body temperature variation and torpor in the numbat, Myrmecobius fasciatus (Marsupialia: Myrmecobiidae). Journal of Thermal Biology 29(6): 277–284.

- Cooper, C. E., and P. C. Withers. 2010. Gross renal morphology of the numbat (Myrmecobius fasciatus) (Marsupialia : Myrmecobiidae). Australian Mammalogy 32(2): 95–97.

- Ellis, E. 2003. Myrmecobius fasciatus. Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved March 19, 2012.

- Friend, T., and A. Burbidge. 2008. Myrmecobius fasciatus. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved March 23, 2012.

- Lee, A. K. 1984. Marsupial carnivores. In D. W. MacDonald, The Encyclopedia of Mammals. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 0871968711.

- Moore, G. F. 1884. Diary of Ten Years. London: M. Walbrook.

- Power, V., C. Lambert, and P. Matson. 2009. Reproduction of the numbat (Myrmecobius fasciatus): Observations from a captive breeding program. Australian Mammalogy 31(1): 25–30.

- World Association of Zoos and Aquariums (WAZA). Numbat. World Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Retrieved March 23, 2012.

- Wilson, D. E., and D. M. Reeder (eds.). 2005. [http://www.bucknell.edu/msw3/browse.asp?id=10800007 Mammal Species of the World (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University. ISBN 9780801882210.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.