Opus Dei

Opus Dei (Latin for "Work of God"), formally known as The Prelature of the Holy Cross and Opus Dei, is an organization of the Roman Catholic Church that emphasizes the belief that everyone is called to holiness and that ordinary life is a path to sanctity.[1][2]

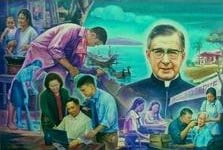

Opus Dei was founded in Spain in 1928 by the Roman Catholic priest JosemarĂa EscrivĂĄ and given final approval in 1950 by Pope Pius XII.[3] In 1982, it was made into a personal prelature â its bishop's jurisdiction is not linked to one specific geographic area, but instead covers the persons in Opus Dei, wherever they are.[3] Opus Dei is the first and so far the only Catholic organization of this type.[4] The Opus Dei prelature is made up of ordinary lay people and secular priests governed by a prelate.[1] Most of its members called supernumeraries, lead traditional family lives and have secular careers. The other three classes of members, numeraries, associates, and numerary-assistants, are celibate, and often live in special centers.[4]

Some ex-members and their families, liberal Catholics, secularists, and supporters of liberation theology have argued that Opus Dei is cult-like, secretive, and highly controlling. John Allen, Jr. and Vittorio Messori, Catholic journalists who studied Opus Dei, state that these allegations are mere myths.[5][6] [7] For Massimo Introvigne, a Catholic sociologist, Opus Dei is intentionally stigmatized by its opponents, because they "cannot tolerate the 'return to religion' of the secularized society."[8] Various Popes and Catholic leaders have strongly supported Opus Dei's innovative teaching on the sanctifying value of work,[9] and in 2002, Pope John Paul II canonized Saint JosemarĂa EscrivĂĄ.[10]

History

Opus Dei was founded by a Roman Catholic priest, JosemarĂa EscrivĂĄ, on October 2, 1928 in Madrid, Spain. According to EscrivĂĄ, on that day he experienced a "vision" in which he "saw Opus Dei."[11] He gave the organization the name "Opus Dei," which in Latin means "Work of God," in order to underscore the belief that the organization was not his (EscrivĂĄ's) work, but was rather God's work.[12] Throughout his life, EscrivĂĄ maintained that the founding of Opus Dei had a supernatural character.[13] EscrivĂĄ summarized Opus Dei's mission as a way of helping ordinary Christians "to understand that their life⊠is a way of holiness and evangelization⊠And to those who grasp this ideal of holiness, the Work offers the spiritual assistance and training they need to put it into practice." [14]

Initially, Opus Dei was open only to men, but in 1930, EscrivĂĄ created a women's branch.[3] In 1936, the organization suffered a temporary setback when rampant killing of ecclesiastics occurred due to the Spanish Civil War, forcing EscrivĂĄ to go into hiding. After the civil war was won by General Francisco Franco's Nationalists, EscrivĂĄ was able to return to Madrid.[3] Escriva said that it was in Spain where Opus Dei found "the greatest difficulties" because of traditionalists who misunderstood Opus Dei's ideas,[15] still Opus Dei flourished during the years of Franco's rule, spreading first throughout Spain, and after 1945, expanding internationally.[3]

In 1939, EscrivĂĄ published The Way, a collection of 999 maxims concerning spirituality.[16] In the 1940s, Opus Dei found an early critic in the Jesuit leader Wlodimir Ledochowski, who told the Vatican that he considered Opus Dei "very dangerous for the Church in Spain," citing its "secretive character" and calling it "a form of Christian Masonry."[17]

In 1946, EscrivĂĄ moved the organization's headquarters to Rome.[3] In 1950, Pope Pius XII granted definitive approval to Opus Dei, thereby allowing married people to join the organization.[3] In 1975, Escriva died and was succeeded by Alvaro del Portillo. In 1982, Opus Dei was made into a personal prelature. This means the Opus Dei related objectives of the members fall under the direct jurisdiction of the Prelate of Opus Dei wherever they are. As to "what the law lays down for all the ordinary faithful," the lay members of Opus Dei, being no different from other Catholics, "continue to be âŠunder the jurisdiction of the diocesan bishop," in the words of John Paul IIÂŽs Ut Sit.[1] In 1994, Javier Echevarria became Prelate upon the death of his predecessor.

One-third of the world's bishops sent letters petitioning for the canonization of EscrivĂĄ.[18] In 2002, approximately 300,000 people gathered in Saint Peter's Square on the day Pope John Paul II canonized JosemarĂa EscrivĂĄ.[19][6]

There are other members whose process of beatification has been opened: Ernesto Cofiño, a father of five children and a pioneer in pediatric research in Guatemala; Montserrat Grases, a teenage Catalan student who died of cancer; Toni Zweifel, a Swiss engineer; and Bishop Alvaro del Portillo.

On September 14, 2005, Benedict XVI blessed a newly-installed statue of Josemaria Escriva placed in a niche of the outside wall of Saint Peter's Basilica. While blessing the six metre white Carrara marble statue, the Pope said he hopes it will serve as inspiration for those who passed by to "do one's daily work in the spirit of Christ." [20]

Doctrine

Opus Dei is an organization within the Roman Catholic church. As such, it ultimately shares the theology of the Catholic Church.

Opus Dei places special emphasis on certain aspects of Catholic doctrine. A central feature of Opus Dei's theology is its focus on the lives of the ordinary Catholics who are neither priests nor monks.[21] Opus Dei emphasizes the "universal call to holiness": the belief that everyone should aspire to be a saint, that sanctity is within the reach of everyone, not just a few special individuals.[22] Opus Dei does not have monks or nuns, and only a minority of its members are part of the priesthood. A related characteristic is Opus Dei's emphasis on uniting spiritual life with professional, social, and family life. Whereas the members of some religious orders might live in monasteries and devote their lives exclusively to prayer and study, members of Opus Dei lead ordinary lives, with traditional families and secular careers, and strive to "sanctify ordinary life." Indeed, Pope John Paul II called EscrivĂĄ "the saint of ordinary life."[23]

Similarly, Opus Dei stresses the importance of work and professional competence.[24] While some religious orders encourage their members to withdraw from the material world, Opus Dei's members are exhorted to "find God in daily life" and to perform their work excellently as a service to society and as a fitting offering to God.[25] Opus Dei teaches that work not only contributes to social progress but is "a path to holiness" and its founder advised members to: "Sanctify your work. Sanctify yourself in your work. Sanctify others through your work."[26]

According to its official literature, some other main features of Opus Dei are: divine filiation, a sense of being children of God; freedom, personal choice and responsibility; and charity.[27]

At the bottom of Escriva's understanding of the âuniversal call to holinessâ are two dimensions, subjective and objective. The subjective is the call given to each person to become a saint, regardless of his place in society. The objective refers to the teaching that all of creation, even the most material situation, is a meeting place with God, and leads to union with Him.[28]

Structure and activities

Leaders of Opus Dei describe the organization as a teaching entity, whereby Catholics are taught to assume personal responsibility in sanctifying the secular world from within. Its lay people and priests organize seminars, workshops, retreats, and classes to help people put the Christian faith into practice in their daily lives. Spiritual direction, one-on-one coaching with a more experienced lay person or priest, is considered the "paramount means" of training. Through these activities they provide religious instruction (doctrinal formation), coaching in spirituality for lay people (spiritual formation), character and moral education (human formation), lessons in sanctifying one's work (professional formation), and know-how in evangelizing one's family and workplace (apostolic formation).

Supporters often liken Opus Dei to a family, and many claim members of Opus Dei resemble the members of the early Christian Churchâordinary workers who seriously sought holiness with nothing exterior to distinguish them from other citizens. [29] In Pope John Paul II's 1982 decree known as the Apostolic constitution Ut Sit, Opus Dei was established as a personal prelature, an official structure of the Catholic Church like a diocese which contains lay people and secular priests who are led by a bishop.[1] In addition to being governed by Ut Sit and by canon law, Opus Dei is governed by the Vatican's Particular Law concerning Opus Dei, otherwise known as Opus Dei's statutes. This specifies the objectives and workings of the prelature. [30]

The head of the Opus Dei prelature is known as the Prelate.[1] The Prelate is the primary governing authority and is assisted by two councils â the General Council (made up of men) and the Central Advisory (made up of women).[31][32] The Prelate holds his position for life.

Opus Dei's highest assembled bodies are the General Congresses, which are usually convened once every eight years. There are separate congresses for the men and women's branch of Opus Dei. The General Congresses are made up of members appointed by the Prelate, and are responsible for advising him about the prelature's future. The men's General Congress also elects the Prelate. After the death of a Prelate, a special elective General Congress is convened. They elect from their ranks one individual to become the next Prelate â an appointment that must be confirmed by the Pope.[33]

Opus Dei runs residential centers throughout the world. These centers provide residential housing for celibate members, undertake recruitment, and provide doctrinal and theological education. Opus Dei is also responsible for a variety of non-profit institutions called âcorporate works of apostolate.â[34] A study of the year 2005, showed that members have cooperated with other people in setting up a total of 608 social initiatives: schools and university residences (68 percent), technical or agricultural training (26 percent), universities, business schools and hospitals (6 percent).[6] The University of Navarra in Pamplona, Spain is a corporate work of Opus Dei which has been rated as one of the top private universities in the country, while its business school, IESE, was adjudged one of the best in the world by the Financial Times and the Economist Intelligence Unit.[35]

Types of membership

Opus Dei is made up of several different types of membership:[4]

Supernumeraries, the largest type, currently account for about 70 percent of the total membership.[36] Typically, supernumeraries are married men and women with careers. Supernumeraries devote a portion of their day to prayer, in addition to attending regular meetings and taking part in activities such as retreats. Due to their career and family obligations, supernumeraries are not as available to the organization as the other types of members, but they typically contribute financially to Opus Dei, and they lend other types of assistance as their circumstances permit.

Numeraries, the second largest type of members of Opus Dei, comprise about 20 percent of total membership.[36] Numeraries are celibate members who usually live in special centers run by Opus Dei. Both men and women may become numeraries, although the centers are strictly gender-segregated.[37] Numeraries generally have careers and devote the bulk of their income to the organization.[38]

Numerary assistants are unmarried, celibate female members of Opus Dei. They live in special centers run by Opus Dei but do not have conventional jobs outside the centers â instead, their professional life is dedicated to looking after the domestic needs of the centers.

Associates are unmarried, celibate members who typically have family or professional obligations.[38] Unlike numeraries and numerary assistants, the associates do not live inside the special Opus Dei centers, but rather live with their families, or wherever is convenient for professional reasons.[39]

The Clergy of the Opus Dei Prelature are priests who are under the jurisdiction of the Prelate of Opus Dei. They are a minority in Opus Deiâ only about two percent of Opus Dei members are part of the clergy.[36] Typically, they are numeraries or associates who ultimately joined the priesthood.

The Priestly Society of the Holy Cross consists of priests associated with Opus Dei. Part of the society is made up of the clergy of the Opus Dei prelature â members of the priesthood who fall under the jurisdiction of the Opus Dei prelature are automatically members of the Priestly Society. Other members in the society are traditional diocesan priests â clergymen who remain under the jurisdiction of a geographically-defined diocese. Technically speaking, such diocesan priests have not "joined" Opus Dei membership, although they have joined a society that is closely affiliated with Opus Dei.[40]

The Cooperators of Opus Dei are those who, despite not being members of Opus Dei, collaborate in some way with Opus Dei â usually through praying, charitable contributions, or by providing some other assistance. Cooperators are not required to be celibate or to adhere to any other special requirements. Indeed, cooperators are not even required to be Christian.[41]

In accordance with Catholic theology, membership is granted when a vocation, or divine calling is presumed to have occurred.

Corporal mortification

Much public attention has focused on Opus Dei's practice of mortification â the voluntary offering up of discomfort or pain to God. Mortification has a long history in many world religions, including the Catholic Church. It has been endorsed by popes as a way of following Christ who died in a bloody crucifixion and who gave this advice: "renounce yourself, take up the cross daily, and follow me."[42] Supporters say that opposition to mortification is rooted in having lost (1) the sense of the enormity of sin or offense against God, (2) the notion of "wounded human nature" and of concupiscence or inclination to sin, and thus the need for "spiritual battle,"[43] and (3) a spirit of sacrifice for "supernatural ends" and not only for physical enhancement.

As a spirituality for ordinary people, Opus Dei focuses on performing sacrifices pertaining to normal duties and to its emphasis on charity and cheerfulness. Additionally, Opus Dei celibate members practice "corporal mortifications" such as sleeping without a pillow or sleeping on the floor, fasting, or remaining silent for certain hours during the day.[44][45] They may also wear a cilice, a small metal chain with inward-pointing spikes that is worn around their upper thigh. The cilice's spikes cause discomfort and may leave small marks, but typically do not cause bleeding. Numeraries in Opus Dei generally wear a cilice for two hours each day.[44]

Although use of the cilice is no longer common, its practice in the Catholic Church is "more widespread than many observers imagine."[6] In modern times it has been used by Blessed Mother Teresa, Saint Padre Pio, and slain archbishop Ăscar Romero.

EscrivĂĄ's opponents point out that his personal mortification practices were even more extreme than the those typically performed by Opus Dei numerariesâ in one incident, EscrivĂĄ flailed himself over a thousand times.[46] Opponents likewise criticize EscrivĂĄ's maxim on suffering: "Loved be pain. Sanctified be pain. Glorified be pain!"[16][44]

Papal support

The bishop of Madrid where Opus Dei was born, Leopoldo Eijo y Garay, supported Opus Dei and defended it in the 1940s by saying that "this opus is truly Dei" (this work is truly God's). Contrary to attacks of secrecy and heresy, the bishop described Opus Dei's founder as someone who is "open as a child" and "most obedient to the Church hierarchy."[47]

In 1960, Pope John XXIII commented that Opus Dei opens up "unsuspected horizons of apostolate."[9] Furthermore, in 1964, Pope Paul VI praised the organization in a handwritten letter to EscrivĂĄ, saying:

Opus Dei is "a vigorous expression of the perennial youth of the Church, fully open to the demands of a modern apostolate... We look with paternal satisfaction on all that Opus Dei has achieved and is achieving for the kingdom of God, the desire of doing good that guides it, the burning love for the Church and its visible head that distinguishes it, and the ardent zeal for souls that impels it along the arduous and difficult paths of the apostolate of presence and witness in every sector of contemporary life.[9]

Despite his praise, the relationship between Paul VI and Opus Dei has been described by one Opus Dei critic as "stormy."[48] After the Second Vatican Council concluded in 1965, Pope Paul VI denied Opus Dei's petition to become a personal prelature.

Pope John Paul I, a few years before his election, wrote that EscrivĂĄ was more radical than other saints who taught about the universal call to holiness. While others emphasized some monastic practices applied to lay people, for EscrivĂĄ "it is the material work itself which must be turned into prayer and sanctity," thus providing a lay spirituality.[49]

With the 1978 election of Pope John Paul II, Opus Dei gained one of its greatest supporters.[50] John Paul II cited Opus Dei's aim of sanctifying secular activities as a "great ideal." He emphasized that EscrivĂĄ's founding of Opus Dei was ductus divina inspiratione, led by divine inspiration, and he granted the organization its status as a personal prelature.[1] Stating that EscrivĂĄ is "counted among the great witnesses of Christianity," John Paul II canonized him in 2002, and called him "the saint of ordinary life."[23] Of the organization, John Paul II said:

[Opus Dei] has as its aim the sanctification of oneâs life, while remaining within the world at oneâs place of work and profession: to live the Gospel in the world, while living immersed in the world, but in order to transform it, and to redeem it with oneâs personal love for Christ. This is truly a great ideal, which right from the beginning has anticipated the theology of the lay state of the Second Vatican Council and the post-conciliar period.[5]

Pope Benedict XVI was also a particularly strong supporter of Opus Dei and of EscrivĂĄ. Pointing to the name "Work of God," Benedict XVI (then Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger), wrote that "The Lord simply made use of [EscrivĂĄ] who allowed God to work." Ratzinger cited EscrivĂĄ for correcting the mistaken idea that holiness is reserved to some extraordinary people who are completely different from ordinary sinners: Even if he can be very weak, with many mistakes in his life, a saint is nothing other than to speak with God as a friend speaks with a friend, allowing God to work, the Only One who can really make the world both good and happy.

Ratzinger spoke of Opus Dei's

surprising union of absolute fidelity to the Churchâs great tradition, to its faith, and unconditional openness to all the challenges of this world, whether in the academic world, in the field of work, or in matters of the economy, etc. ... the theocentrism of EscrivĂĄ...means this confidence in the fact that God is working now and we ought only to put ourselves at his disposal...This, for me, is a message of greatest importance. It is a message that leads to overcoming what could be considered the great temptation of our times: the pretense that after the 'Big Bang' God retired from history.[12]

However, on July 22, 2022, Pope Francis revoked Opus Deiâs status as a personal prelature, issuing âAd charisma tuendum,â a motu proprio, or change to church law by way of his personal authority, which effectively allows for greater Vatican scrutiny of Opus Deiâs activities and actions. Pope Francis stated that with the change, his hope was that Opus Dei would become more focused on charism, âthe call to holiness in the world, through the sanctification of work and family and social commitments.â[51]

Controversy

Criticism

Opus Dei has been called "the most controversial force in the Catholic Church,"[6] and EscrivĂĄ has been described as a "polarizing" figure. In the English-speaking world, the most vocal critic of Opus Dei is a group called the Opus Dei Awareness Network (ODAN), a non-profit organization that exists "to provide education, outreach and support to people who have been adversely affected by Opus Dei." ODAN is headed by Diane DiNicola, mother of a former member, Tammy DiNicola. [52] Other critics include former members of Opus Dei, liberal catholic theologians such as Fr. James Martin, a Jesuit, and supporters of Liberation theology, such as Penny Lernoux and Michael Walsh, an ex-Jesuit.[36]

Critics state that Opus Dei is "intensely secretive"â for example, members generally do not publicly disclose their affiliation with Opus Dei, and under the 1950 constitution, members were expressly forbidden to reveal themselves without the permission of their superiors. Opus Dei has been accused of deceptive and aggressive recruitment practices such as showering potential members with intense praise ("Love bombing"),[53] instructing numeraries to form friendships and attend social gatherings explicitly for recruiting purposes,[38] and even requiring regular written reports from its members about those friends who are potential recruits.[54] Most of all, critics allege that the group maintains an extremely high degree of control over its membersâ there used to be a time when numeraries submitted their incoming and outgoing mail to their superiors to read, and members are forbidden to read certain books without permission from their superiors.[55] Critics charge that Opus Dei pressures numeraries to sever contact with non-members, including their own families.[53]

Critics assert that EscrivĂĄ and the organization supported the government of Francisco Franco.[56]

Concerning the group's role in the Catholic Church, critics have argued that Opus Dei's unique status as a personal prelature gives it too much independence, making it essentially a "church within the church."[57] Some critics claim that Opus Dei exerts a disproportionately large influence within the Catholic Church itself, citing for example the unusually rapid canonization of EscrivĂĄ, which some considered to be irregular.[58] Lastly, Opus Dei, as a part of the Roman Catholic Church, also shares any criticisms of Catholicism in generalâ for example, the fact that female members of Opus Dei cannot become priests or prelates.

Replies to criticism

Supporters of Opus Dei contend that Opus Dei has been falsely maligned.[59][53] John Allen explained this view by saying:

There are really two Opus Deis. The Opus Dei of myth, which is a vast, immensely wealthy and powerful cult metastasizing at the heart of Catholicism; and the Opus Dei of reality, which is a small lay group with relatively modest means propagating a spiritual path of interest to a certain kind of fairly traditional Catholic.[60]

To explain the celibate lifestyle of numeraries and their relationship with their family, supporters quote Jesus' comment in Matthew 10:37 that "He who loves his father or mother more than me is not worthy of me." [61]

Supporters deny that support of Franco during the Spanish Civil War was unique to Opus Dei. As Allen observed:

Itâs worth noting that in the context of the Spanish Civil War, in which anticlerical Republican forces killed 13 bishops, 4,000 diocesan priests, 2,000 male religious, and 300 nuns, virtually every group and layer of life in the Catholic Church in Spain was âpro-Franco.â[6]

Peter Berglar, a German historian and Opus Dei member, argued that connecting Opus Dei with the Franco government is a "gross slander," because there were notable members of Opus Dei who were vocal critics of the Franco Regime.[62] Allen said that Escriva was staunchly non-political, and repeatedly stressed that freedom is an essential element of Opus Dei. He said that Escriva's relatively quick canonization does not have anything to do with power but with improvements in procedures and John Paul II's decision to make Escriva's sanctity and message known.[6]

Supporters of Opus Dei have also questioned the motives and reliability of some critics. Sociologists like Bryan R. Wilson point out that some former members of any religious group may have psychological or emotional motivations to criticize their former groups, and they claim that such individuals are prone to create fictitious "atrocity stories" which have no basis in reality.[63] Many supporters of Opus Dei have expressed the belief that the criticisms of Opus Dei stem from a generalized disapproval of spirituality, Christianity, or Catholicism. Massimo Introvigne, a sociologist, argues that critics employ the term "cult" in order to intentionally stigmatize Opus Dei because "they cannot tolerate 'the return to religion' of the secularized society."[8]

Regarding women, Allen reports that half of the leadership positions in Opus Dei are held by women, and they supervise men.[64] The Catholic Church emphasizes that "the greatest in the Kingdom of Heaven are not the ministers but the saints."

Lastly, some supporters of Opus Dei have viewed the controversy surrounding the organization as a "Sign of contradiction," in reference to the biblical quote of Jesus Christ as a "sign that is spoken against."[65]

Opus Dei in popular culture

Since 2003, Opus Dei has received world attention as a result of Dan Brown's novel The Da Vinci Code[66] and the 2006 film based on the novel.[67] In The Da Vinci Code, Opus Dei is portrayed as a Catholic organization that is led into a sinister international conspiracy.[68]

In general, The Da Vinci Code has been sharply criticized for its numerous factual inaccuracies, and its conspiracy theory has been debunked by a wide array of scholars and historians. [69] According to the Bishop of Durham, the Rt Rev Dr Tom Wright, the novel is a "great thriller" but "lousy history."[70] For example, the major villain in The Da Vinci Code is a monk who is member of Opus Dei â but in reality there are no monks in Opus Dei. The Da Vinci Code implies that Opus Dei is the Pope's personal prelature â but the term "personal prelature" does not refer to a special relationship to the Pope: It means an institution in which the jurisdiction of the prelate is not linked to a geographic territory but over persons, wherever they be. Nonetheless, Brown claims that his portrayal of Opus Dei was based on interviews with past and present members.[71]

Notes

- â 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Pope John Paul II, Apostolic constitution "Ut sit". Retrieved July 17, 2023.

- â Address of John Paul II in Praise of St. Josemaria, Founder of Opus Dei Retrieved July 17, 2023.

- â 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Historical Overview Opus Dei Official Site. Retrieved July 17, 2023.

- â 4.0 4.1 4.2 Opus Dei BBC Religion and Ethics. Retrieved July 17, 2023.

- â 5.0 5.1 Opus Deiâs focus on secular life Opus Dei Official Site. Retrieved July 17, 2023.

- â 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 John Allen, Jr., Opus Dei: an Objective Look Behind the Myths and Reality of the Most Controversial Force in the Catholic Church (Doubleday Religion, 2005, ISBN 0385514492).

- â Vittorio Messori, Opus Dei, Leadership and Vision in Today's Catholic Church (Regnery Publishing, 1997, ISBN 0895264501).

- â 8.0 8.1 Massimo Introvigne, CESNUR, 1994. Retrieved July 17, 2023.

- â 9.0 9.1 9.2 Papal statements on Opus Dei Opus Dei Official Site. Retrieved July 17, 2023.

- â St. JosemarĂa Escriva de Balaguer Catholic Online. Retrieved July 17, 2023.

- â Biographical Timeline of St. Josemaria Escriva Opus Dei. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- â 12.0 12.1 Pope Benedict XVI on St. Josemaria Escriva Opus Dei (May 18, 2005). Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- â The Founding of Opus Dei Opus Dei. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- â JosemarĂa Escriva, Conversations 60 Studium Foundation. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- â Josemaria EscrivĂĄ, Conversations 33 Studium Foundation. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- â 16.0 16.1 JosemarĂa EscrivĂĄ, The Way (Scepter Pubs, 2003 (original 1939), ISBN 978-1889334424).

- â Philip Copens, The Dan Brown Phenomenon â The Da Vinci Code: The Work of Sion Eye of the Psychic. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- â Blessed JosemarĂa EscrivĂĄ to be canonized October 6, 2002 Opus Dei. Retrieved July 26, 2023.

- â John L. Allen Jr., 300,000 pilgrims turn out for canonization of Opus Dei founder National Catholic Reporter (October 18, 2002). Retrieved July 26, 2023.

- â Pope Blesses Statue of Opus Dei Founder Religion News Blog (September 14, 2005). Retrieved July 26, 2023.

- â Fr. John McCloskey, The Pope and Opus Dei The Mary Foundation. Retrieved July 26, 2023.

- â Terry Gross, A Glimpse Inside a Catholic 'Force': Opus Dei National Public Radio (November 28, 2005). Retrieved July 26, 2023.

- â 23.0 23.1 Jeff Morrow, JosemarĂa EscrivĂĄ: The Saint of Ordinary Life The Imaginative Conservative (June 25, 2022). Retrieved July 26, 2023.

- â JosemarĂa EscrivĂĄ, Furrow (Scepter Publishers, 1992 (original 1934), ISBN 978-0933932555).

- â JosemarĂa EscrivĂĄ, Conversations 60 Studium Foundation. Retrieved July 26, 2023.

- â Carlos Llano, Professional Ethics and Sanctification of Work Romana 38 (January-June 2004): 112-126. Retrieved July 26, 2023.

- â Message Opus Dei. Retrieved July 26, 2023.

- â Opus Dei â Foundation and Purpose Apologetics Index. Retrieved July 26, 2023.

- â Domingo Ramos-LissĂłn, The Example of the Early Christians in Blessed Josemaria's Teachings Romana 29. Retrieved July 29, 2023.

- â Place in the Church Opus Dei. Retrieved July 29, 2023.

- â Dennis Dubro, Government, Direction and Control in Opus Dei ODAN Opus Dei Awareness Network. Retrieved July 29, 2023.

- â Organization of the Prelature Opus Dei. Retrieved July 29, 2023.

- â Statutes of Opus Dei Opus Dei (October 5, 2022). Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- â Apostolic Initiatives Opus Dei (February 10, 2006). Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- â IESE Business School University of Navarra. Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- â 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 Ron Grossman, Catholics scrutinize enigmatic Opus Dei Chicago Tribune (December 15, 2003). Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- â Gordon Urquhart, Conservative Catholic Influence in Europe Catholics for a Free Choice, 1997. Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- â 38.0 38.1 38.2 James Martin, S.J., Opus Dei In the United States America: The Jesuit Review (February 25, 1995). Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- â Christians in the Middle of the World Opus Dei (January 27, 2014). Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- â The Priestly Society of the Holy Cross Opus Dei (March 10, 2014). Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- â Cooperators of Opus Dei Opus Dei. Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- â Opus Dei and corporal mortification Opus Dei (January 20, 2005). Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- â Catechism of the Catholic Church no. 405 Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- â 44.0 44.1 44.2 Corporal Mortification in Opus Dei Opus Dei Awareness Network (May 13, 2002). Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- â David Ruppe, Opus Dei: A Return to Tradition ABC News (June 18, 2001). Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- â Sharon Clasen, Making Modern-Day Martyrs using Medieval Methods Opus Dei Awareness Network (April 14, 2005). Retrieved August 4, 2023

- â AndrĂ©s VĂĄzquez de Prada, The Founder of Opus Dei: The life of JosemarĂa EscrivĂĄ, Volume 1: The early years (Scepter Pubs, 2001, ISBN 978-1889334257).

- â Ruth Bertels, The Ethics of Opus Dei Opus-Info. Retrieved August 5, 2023.

- â Michael Pakaluk, Opus Dei, In Everyday Life EWTN. Retrieved August 5, 2023.

- â Opus Dei Source Watch. Retrieved August 5, 2023.

- â Alessandro De Carolis, Motu Proprio on Opus Dei to protect charism and promote evangelization Vatican News (July 22, 2022). Retrieved August 5, 2023.

- â About ODAN Opus Info. Retrieved August 5, 2023.

- â 53.0 53.1 53.2 Abbott Karloff, Opus Dei members: 'Da Vinci' distorted Religion News Blog (May 15, 2006). Retrieved August 5, 2023.

- â Opus Dei's Questionable Practices Opus Dei Awareness Network. Retrieved August 5, 2023.

- â Paul Moses, Fact, Fiction And Opus Dei Newsday (August 26, 2003). Retrieved August 5, 2023.

- â Giles Tremlett, Sainthood beckons for priest linked to Franco The Guardian (October 5, 2002). Retrieved August 5, 2023.0

- â Opus Dei - A Church Within the Church Documentary Tube. Retrieved August 5, 2023.

- â Paul Baumann, Let There Be Light: A look inside the hidden world of Opus Dei Washington Monthly (October 1, 2005). Retrieved August 5, 2023.

- â Peter Gould, The rise of Opus Dei BBC News (October 4, 2002). Retrieved August 5, 2023.

- â The `Realâ Silas Considers `Da Vinci Codeâ a `Fictional Blasphemyâ Religion News Service (April 28, 2006). Retrieved August 5, 2023.

- â Christoph Schönborn, O.P., Are there sects in the Catholic Church? Eternal Word Television Network. Retrieved August 5, 2023.

- â Peter Berglar, Opus Dei: Life and Work of Its Founder, Josemaria Escriva (Scepter Pubs, 1995, ISBN 0933932650).

- â Bryan R. Wilson, Apostates and New Religious Movements December 3, 1994. Retrieved August 5, 2023.

- â Julia Baird, Tall tale ignites an overdue debate The Sydney Morning Herald (May 18, 2006). Retrieved August 5, 2023.

- â Vittorio Messori, Opus Dei, Leadership and Vision in Today's Catholic Church (Gateway Books, 1997, ISBN 978-0895264503).

- â Dan Brown, The Da Vinci Code (Doubleday, 2003, ISBN 978-5550155189).

- â The Da Vinci Code (2006) IMDb. Retrieved August 5, 2023.

- â Nicole Zarayn, Opus Dei and The Da Vinci Code National Catholic Reporter (September 10, 2004). Retrieved August 5, 2023.

- â Bart Ehrman, Truth and Fiction in The Da Vinci Code: A Historian Reveals What We Really Know about Jesus, Mary Magdalene, and Constantine (Oxford University Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0195181401).

- â Da Vinci Code is 'lousy history' BBC News (December 24, 2004). Retrieved August 5, 2023.

- â Steve Bloomfield, Opus Dei: Jack Valero speaks for an evil sect, says 'The Da Vinci Code' Independent (May 14, 2006). Retrieved August 5, 2023.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Allen, John, Jr. Opus Dei: an Objective Look Behind the Myths and Reality of the Most Controversial Force in the Catholic Church. Doubleday Religion, 2005. ISBN 0385514492

- Berglar, Peter. Opus Dei: Life and Work of Its Founder, Josemaria Escriva Scepter Pubs, 1995. ISBN 0933932650

- Brown, Dan. The Da Vinci Code. Doubleday, 2003. ISBN 978-5550155189

- Coverdale, John. Uncommon Faith, Scepter Publishers, 2002. ISBN 188933474X

- Ehrman, Bart. Truth and Fiction in The Da Vinci Code: A Historian Reveals What We Really Know about Jesus, Mary Magdalene, and Constantine. Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0195181401

- EscrivĂĄ, JosemarĂa. Furrow. Scepter Publishers, 1992 (original 1934). ISBN 978-0933932555

- EscrivĂĄ, JosemarĂa. The Way. Scepter Pubs, 2003 (original 1939). ISBN 978-1889334424

- Estruch, Joan. Saints and Schemers: Opus Dei and its paradoxes. Oxford University Press, 1995.

- Hahn, Scott. Ordinary Work, Extraordinary Grace: My Spiritual Journey in Opus Dei. Random House Double Day Religion, 2006. ISBN 9780385519243

- Le Tourneau, Dominique. What Is Opus Dei? Gracewing, 2002. ISBN 0852441363

- Messori, Vittorio. Opus Dei, Leadership and Vision in Today's Catholic Church. Gateway Books, 1997. ISBN 978-0895264503

- O'Connor, William. Opus Dei: An Open Book. A Reply to "The Secret World of Opus Dei" by Michael Walsh, Dublin: Mercier Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0853429876

- VĂĄzquez de Prada, AndrĂ©s, The Founder of Opus Dei: The life of JosemarĂa EscrivĂĄ, Volume 1: The early years. Scepter Pubs, 2001. ISBN 978-1889334257

- Walsh, Michael. Opus Dei: An Investigation into the Powerful Secretive Society within the Catholic Church, San Francisco: Harper, 2004. ISBN 978-0060750688

External links

All links retrieved July 17, 2023.

Sites supporting Opus Dei

Sites critical of Opus Dei

- Opus Dei Awareness Network - by ex-members and family

- Opus Libros - by ex-members, in Spanish

- The Unofficial Opus Dei FAQ - by Franz Schaefer

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.