Persepolis

| Persepolis* | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| State Party | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, iii, vi |

| Reference | 114 |

| Region** | Asia-Pacific |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1979 (3rd Session) |

| * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. ** Region as classified by UNESCO. | |

Persepolis (Old Persian: 'Pars', New Persian: تخت جمشید, 'Takht-e Jamshid') was an ancient ceremonial capital of the second Iranian dynasty, the Achaemenid Empire, situated some 70 km northeast of modern city of Shiraz. It was built by Darius the Great, beginning around 518 B.C.E. To the ancient Persians, the city was known as Parsa, meaning the city of Persians, Persepolis being the Greek interpretation of the name (Περσες (meaning Persian)+ πόλις (meaning city)). In contemporary Iran the site is known as Takht-e Jamshid (Throne of Jamshid).

Persepolis has a long and complex history, designed to be the central city of the ever expanding Persian empire, besieged and destroyed by Alexander the Great, rebuilt and yet again left to waste, the city has produced many fascinating archaeological finds and is a symbol of contemporary Iranian pride. Although maintained as a ruin, it is impressive, commanding a sense of awe. Visitors to this ancient site can well imagine its beauty and splendor and mourn the destruction of its majesty.

History

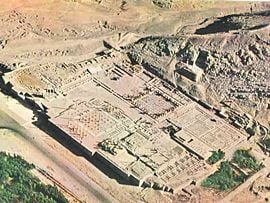

Archaeological evidence suggests that the earliest remains of Persepolis date from around 518 B.C.E. It is believed that Darius the Great chose the area on a terrace at the foot of mountains to build a city in honor of the Persian empire.[1] The site is marked by a large 125,000 square meter terrace, partly artificial and partly cut out of a mountain, with its east side leaning on Kuh-e Rahmet ("the Mountain of Mercy"). The other three sides are formed by a retaining wall, which varies in height with the slope of the ground. From five to 13 meters on the west side there is a double stair, gently sloping, which leads to the top. To create the level terrace, any depressions that were present were filled up with soil and heavy rocks. They joined the rocks together with metal clips. Darius ordered the construction of Apadana Palace and the Debating hall (Tripylon or the three-gated hall), the main imperial Treasury and its surroundings, which were completed at the time of the reign of his son, King Xerxes I.

The designers were greatly influenced by the Mesopotamians in their construction, and when a significant portion of the city was completed, Darius declared it the new capital of Persia, replacing Pasargadae. However, this was largely symbolic; Susa and Babylon acted as the real centers of governance, while Persepolis was an area of palaces, treasures, and tombs.[2] Festivities and rituals were performed there, but outside the care taking staff and the occasional visiting official, the city was not occupied by a large population. Further construction of the buildings at the terrace continued until the downfall of the Achaemenid dynasty.

In about 333 B.C.E. during his invasion of Persia, Alexander the Great sent the bulk of his army to Persepolis. By the Royal Road, Alexander stormed and captured the Persian Gates (in the modern Zagros Mountains), then took Persepolis before its treasury could be looted. After several months Alexander allowed the troops to loot Persepolis.[3] A fire broke out in the eastern palace of Xerxes and spread to the rest of the city. This was not the end of Persepolis however.

In 316 B.C.E. Persepolis was still the capital of Persia as a province of the great Macedonian Empire. The city must have gradually declined in the course of time; but the ruins of the Achaemenidae remained as a witness to its ancient glory. It is probable that the principal town of the country, or at least of the district, was always in this neighborhood. About 200 C.E. the city Istakhr (properly Stakhr) was established on the site of Persepolis. There the foundations of the second great Persian Empire were laid, and Istakhr acquired special importance as the center of priestly wisdom and orthodoxy. The Sassanian kings covered the faces of the rocks in this neighborhood, and in part even the Achaemenian ruins, with their sculptures and inscriptions, and must themselves have built largely here, although never on the same scale of magnificence as their ancient predecessors.

At the time of the Arabian conquest Istakhr offered a desperate resistance, but the city was still a place of considerable importance in the first century of Islam, although its greatness was speedily eclipsed by the new metropolis Shiraz. During the following centuries Istakhr gradually declined, until, as a city, it ceased to exist. This fruitful region, however, was covered with villages until the frightful devastations of the eighteenth century; and even now it is, comparatively speaking, well cultivated. The "castle of Istakhr" played a conspicuous part several times during the Muslim period as a strong fortress. It was the middlemost and the highest of the three steep crags which rise from the valley of the Kur, at some distance to the west or north-west of Nakshi Rustam.[4]

Discovery

The first scientific excavation at Persepolis was carried out by Ernst Herzfeld in 1931, commissioned by the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. He believed the reason behind the construction of Persepolis was the need for a majestic atmosphere, as a symbol for their empire and to celebrate special events, especially the “Nowruz,” (the Iranian New Year held on March 21). For historical reasons and deep rooted interests it was built on the birthplace of the Achaemenid dynasty, although this was not the center of their Empire at that time. For three years Hezfeld's team worked to uncover the Eastern stairwell of the Apadana, the main terrace, the stairs of the council hall and the harem of Xerxes. In 1934, Erich F. Schmidt took over the expedition and cleared out larger sections of the complex.[5]

Ruins

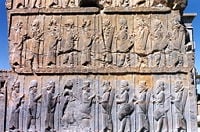

On the terrace are the ruins of a number of colossal buildings, all constructed of dark-grey marble from the adjacent mountain. A few of the remaining pillars are still intact, standing in the ruins. Several of the buildings were never finished. These ruins, for which the name Chehel minar ("the forty columns or minarets"), can be traced back to the thirteenth century, are now known as Takht-e Jamshid - تخت جمشید ("the throne of Jamshid").

Behind Takht-e Jamshid are three sepulchers hewn out of the rock in the hillside. The facades, one of which is incomplete, are richly decorated with reliefs. About 13 km NNE, on the opposite side of the Pulwar, rises a perpendicular wall of rock, in which four similar tombs are cut, at a considerable height from the bottom of the valley. The modern Persians call this place Naqsh-e Rustam - نقش رستام or Nakshi Rostam ("the picture of Rostam"), from the Sassanian reliefs beneath the opening, which they take to be a representation of the mythical hero Rostam. That the occupants of these seven tombs were kings might be inferred from the sculptures, and one of those at Nakshi Rustam is expressly declared in its inscription to be the tomb of Darius Hystaspis.[6]

The Gate of All Nations

The Gate of all Nations, referring to subjects of the empire, consisted of a grand hall that was almost 25 square meters, with four columns and its entrance on the Western Wall. There were two more doors, one to the south which opened to the Apadana yard and the other one opened onto a long road to the east. Pivoting devices found on the inner corners of all the doors indicate that they were two-leafed doors, probably made of wood and covered with sheets of ornate metal. A pair of Lamassus, bulls with the head of a bearded man, stand on the western threshold, and another pair with wings and a Persian head (Gopät-Shäh) on the eastern entrance, to reflect the Empire’s power. Xerxes' name was written in three languages and carved on the entrances, informing everyone that he ordered this to be built.

Apadana Palace

Darius the Great built the greatest and most glorious palace at Persepolis in the western side. This palace was named Apadana and was used for the King of Kings' official audiences. The work began in 515 B.C.E. and was completed 30 years later, by his son Xerxes I. The palace had a grand hall in the shape of a square, each side 60m long with seventy-two columns, thirteen of which still stand on the enormous platform. Each column is 19m high with a square Taurus and plinth. The columns carried the weight of the vast and heavy ceiling. The tops of the columns were made from animal sculptures such as two headed bulls, lions and eagles. The columns were joined to each other with the help of oak and cedar beams, which were brought from Lebanon. The walls were covered with a layer of mud and stucco to a depth of 5cm, which was used for bonding, and then covered with the greenish stucco which is found throughout the palaces.

At the western, northern and eastern sides of the palace there was a rectangular veranda which had twelve columns in two rows of six. At the south of the grand hall a series of rooms were built for storage. Two grand Persepolitan stairways were built, symmetrical to each other and connected to the stone foundations. To avoid the roof being eroded by rain vertical drains were built through the brick walls. In the Four Corners of Apadana, facing outwards, four towers were built.[7]

The walls were tiled and decorated with pictures of lions, bulls, and flowers. Darius ordered his name and the details of his empire to be written in gold and silver on plates, and to place them in covered stone boxes in the foundations under the Four Corners of the palace. Two Persepolitan style symmetrical stairways were built on the northern and eastern sides of Apadana to compensate for a difference in level. There were also two other stairways in the middle of the building.[8] The external front views of the palace were embossed with pictures of the Immortals, the Kings' elite guards. The northern stairway was completed during Darius' reign, but the other stairway was completed much later.

The Throne Hall

Next to the Apadana, second largest building of the Terrace and the final edifices, is the Throne Hall or the Imperial Army's hall of honor (also called the "Hundred-Columns Palace). This 70x70 square meter hall was started by Xerxes and completed by his son Artaxerxes I by the end of the fifth century B.C.E. Its eight stone doorways are decorated on the south and north with reliefs of throne scenes and on the east and west with scenes depicting the king in combat with monsters. In addition, the northern portico of the building is flanked by two colossal stone bulls.

In the beginning of Xerxes's reign the Throne Hall was used mainly for receptions for military commanders and representatives of all the subject nations of the empire, but later the Throne Hall served to be as an imperial museum.[9]

Other palaces & structures

There were other palaces built, these included the Tachara palace which was built under Darius I; the Imperial treasury which was started by Darius in 510 B.C.E. and finished by Xerxes in 480 B.C.E.; and the Hadish palace by Xerxes I, which occupies the highest level of terrace and stand on the living rock. Other structures include: the Council Hall, the Tryplion Hall, the palaces of D, G, H, storerooms, stables and quarters, unfinished gateway, and a few miscellaneous structures at Persepolis near the south-east corner of the Terrace, at the foot of the mountain.

Tombs of King of Kings

The kings buried at Naghsh-e Rustam are probably Darius the Great, Xerxes I, Artaxerxes I, and Darius II. Xerxes II, who reigned for a very short time, could scarcely have obtained so splendid a monument, and still less could the usurper Sogdianus (Secydianus). The two completed graves behind Takhti Jamshid would then belong to Artaxerxes II and Artaxerxes III. The unfinished one is perhaps that of Arses of Persia, who reigned at the longest two years, or, if not his, then that of Darius III (Codomannus), who is one of those whose bodies are said to have been brought "to the Persians."

Another small group of ruins in the same style is found at the village of Hajjiäbäd, on the Pulwar, a good hour's walk above Takhti Jamshid. These formed a single building, which was still intact 900 years ago, and was used as the mosque of the then existing city of Istakhr.

Modern events

Modern day Iranians view the ruins of Persepolis in a fashion similar to how modern Egyptians view the pyramids: symbols of national pride. In 1971, Persepolis was the main staging ground for the 2,500 year celebration of Iran's monarchy. The UNESCO declared the citadel of Persepolis a World Heritage Site in 1979, acknowledging it as a site of significant historical and archaeological value. The site is maintained by the Iranian Cultural Heritage Foundation. Very little is allowed to be altered or enhanced, leaving the ruins as they are. Special permits are occasionally granted to archaeological expeditions.

The site continues to be one of the most popular tourist attraction in Iran, easily accessible from the closest city, Shiraz. Although it is decidedly a ruin, yet it remains impressive:

Even today, those who step up to its gigantic terrace of 125,000 square meters and see its majestic columns are filled with a sense of awe drifting into a dream-like trance. A dream in which one tries to visualize the beauty and dazzling splendor of Persepolitan palaces before their sad destruction.[10]

Gallery

Notes

- ↑ Iranian Cultural and Information Center (1997) "Persepolis" Retrieved November 2, 2007

- ↑ "Persepolis" The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. Columbia University Press, 2003. Answers.com 02 Nov. 2007.

- ↑ Nigel Rodgers, The Rise and Fall of Ancient Greece: The Military And Political History Of The Ancient Greeks From The Fall Of Troy, The Persian Wars And The Battle Of … Alexander The Great And His Conquest Of Asia. (London: Lorenz Books, 2007)

- ↑ Donald Whitcomb (2003) Archaeology and the Meanings of Persepolis The Oriental Institute University of Chicago

- ↑ Iran Chamber Society (2007) "Parse or Persepolis" Retrieved November 2, 2007

- ↑ Donald Newton Wilber, Persepolis: The Archaeology of Parsa, Seat of the Persian Kings. (Darwin Press, 1989. ISBN 0878500626)

- ↑ David Stronach and Kim Codella (2007) "Persepolis" The Circle of Ancient Iranian Studies (CAIS) Retrieved November 2, 2007

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Maria Brosius, Persians: An Introduction (Peoples of the Ancient World) (London: Routledge, 2006)

- ↑ Persepolis Recreated - The Movie Documentary7.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brosius, Maria. 2006. Persians: An Introduction (Peoples of the Ancient World. London: Routledge. ISBN 0415320909

- Burkert, Walter. 2007 Babylon, Memphis, Persepolis: Eastern Contexts of Greek Culture. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674023994

- Curtis, J. and N. Tallis, (eds). 2005. Forgotten Empire: The World of Ancient Persia. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520247310.

- Rich, Claudis James. 2002. Narrative of a Residence in Koordistan, and on the Site of Ancient Nineveh: With journal of a voyage down the Tigris to Bagdad and an account of a visit … Persepolis. Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 1402192878

- Rodgers, Nigel. 2007. The Rise and Fall of Ancient Greece: The Military And Political History Of The Ancient Greeks From The Fall Of Troy, The Persian Wars And The Battle Of … Alexander The Great And His Conquest Of Asia. London: Lorenz Books, Anness Press. ISBN 0754817334

- Wilber, Donald Newton. 1989. Persepolis: The Archaeology of Parsa, Seat of the Persian Kings. Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press. ISBN 0878500626.

External links

All links retrieved November 23, 2022.

- Persepolis Satellite view @ Google Maps

- Persepolis

- Persepolis Photographs and Introduction to the Persian Expedition, Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

- Persepolis

- 3D reconstructed pictures and movies of Persepolis

- Persepolis Fortification Archive Project

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.