Petra

| Petra* | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| |

| State Party | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, iii, iv |

| Reference | 326 |

| Region** | Arab States |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1985Â (9th Session) |

| * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. ** Region as classified by UNESCO. | |

Petra (from ÏÎÏÏα "petra-ÏÎÏÏα," cleft in the rock in Greek; Arabic: اÙبتراء, Al-ButrÄ) is an archaeological site in the Arabah, Ma'an Governorate, Jordan. It lies on the slope of Mount Hor in a basin among the mountains which form the eastern flank of Arabah (Wadi Araba), the large valley that stretches from the Dead Sea to the Gulf of Aqaba.

The ancient city sits in the Negev Desert's Valley of Moses, enclosed by sandstone cliffs veined with shades of red and purple varying to pale yellow, prompting its description as a "rose-red city half as old as Time" by the 19th-century biblical scholar John William Burgon.

Archaeological evidence points to habitation during Paleolithic and the Neolithic periods. Edomites occupied the area about 1200 B.C.E., and the biblical land of Sela is believed to have been renamed Petra. The Nabataeans, an Arab tribe, occupied it and made it the capital of their kingdom. Under their rule the city prospered as a center of trade in spice, ivory, incense, and textiles with lands as distant as China and India, Egypt, and the Mediterranean.

The site remained unknown to the Western world until 1812, when it was discovered by Swiss explorer and Islamist Johann Ludwig Burckhardt. In 1985 UNESCO listed Petra as a World Heritage Site, describing it as "one of the most precious properties of man's cultural heritage." Today it is one of the world's most famous archaeological sites, where ancient Eastern traditions blend with Hellenistic architecture.

The ruins of Petra serve as testimony of an ancient people who built a lively desert metropolis through human ingenuity, devising an elaborate water management system, carving towering constructions into native rock, and honoring their leaders and kings in monumental and intricately detailed tombs.

Geography

Rekem is an ancient name for Petra and appears in Dead Sea scrolls[1] associated with Mount Seir. Additionally, Eusebius (c. 275 â 339) and Jerome (ca. 342 â 419)[2] assert that Rekem was the native name of Petra, supposedly on the authority of Josephus (37 â c. 100 C.E.).[3] Pliny the Elder and other writers identify Petra as the capital of the Nabataeans, Aramaic-speaking Semites, and the center of their caravan trade. Enclosed by towering rocks and watered by a perennial stream, Petra not only possessed the advantages of a fortress, but controlled the main commercial routes which passed through it to Gaza in the west, to Bosra and Damascus in the north, to Aqaba and Leuce Come on the Red Sea, and across the desert to the Persian Gulf. The latitude is 30° 19' 43" N and the longitude is 35° 26' 31" E.

Excavations have demonstrated that it was the ability of the Nabataeans to control the water supply that led to the rise of the desert city, in effect creating an artificial oasis. The area is visited by flash floods and archaeological evidence demonstrates the Nabataeans controlled these floods by the use of dams, cisterns and water conduits. These innovations stored water for prolonged periods of drought, and enabled the city to prosper from its sale.[4][5]

Although in ancient times Petra might have been approached from the south (via Saudi Arabia on a track leading around Jabal Haroun, Aaron's Mountain, on across the plain of Petra), or possibly from the high plateau to the north, most modern visitors approach the ancient site from the east. The impressive eastern entrance leads steeply down through a dark, narrow gorge (in places only 3â4 meters wide) called the Siq ("the shaft"), a natural geological feature formed from a deep split in the sandstone rocks and serving as a waterway flowing into Wadi Musa. At the end of the narrow gorge stands Petra's most elaborate ruin, Al Khazneh ("the Treasury"), hewn into the sandstone cliff.

A little further from the Treasury, at the foot of the mountain called en-Nejr is a massive theater, so placed as to bring the greatest number of tombs within view. At the point where the valley opens out into the plain, the site of the city is revealed with striking effect. The amphitheater has actually been cut into the hillside and into several of the tombs during its construction. Rectangular gaps in the seating are still visible. Almost enclosing it on three sides are rose-colored mountain walls, divided into groups by deep fissures, and lined with knobs cut from the rock in the form of towers.

History

The History of Petra begins with the Kites and cairns of gazelle hunters going back into the acermaic neolithic. Evidence suggests that settlements had begun in and around there in the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt. (It is listed in Egyptian campaign accounts and the Amarna letters as Pel, Sela or Seir). Though the city was founded relatively late, a sanctuary existed there since very ancient times. Stations 19 through 26 of the stations list of Exodus are places associated with Petra and it is referred to there as "the cleft in the rock."[6] This part of the country was biblically assigned to the Horites, the predecessors of the Edomites.[7] The habits of the original natives may have influenced the Nabataean custom of burying the dead and offering worship in half-excavated caves. Although Petra is usually identified with Sela which also means a rock, the Biblical references[8] refer to it as the cleft in the rock, referring to its entrance. 2 Kings xiv. 7 seems to be more specific. In the parallel passage, however, Sela is understood to mean simply "the rock" (2 Chr. xxv. 12, see LXX).

On the authority of Josephus (Antiquities of the Jews iv. 7, 1~ 4, 7), Eusebius and Jerome (Onom. sacr. 286, 71. 145, 9; 228, 55. 287, 94), assert that Rekem was the native name, and Rekem appears in the Dead Sea scrolls as a prominent Edom site most closely describing Petra. But in the Aramaic versions Rekem is the name of Kadesh, implying that Josephus may have confused the two places. Sometimes the Aramaic versions give the form Rekem-Geya which recalls the name of the village El-ji, southeast of Petra. The capital, however, would hardly be defined by the name of a neighboring village. The Semitic name of the city, if not Sela, remains unknown. The passage in Diodorus Siculus (xix. 94â97) which describes the expeditions which Antigonus sent against the Nabataeans in 312 B.C.E. is understood to throw some light upon the history of Petra, but the "petra" referred to as a natural fortress and place of refuge cannot be a proper name and the description implies that the town was not yet in existence.

More satisfactory evidence of the date of the earliest Nabataean settlement may be obtained from an examination of the tombs. Two types may be distinguishedâthe Nabataean and the Greco-Roman. The Nabataean type starts from the simple pylon-tomb with a door set in a tower crowned by a parapet ornament, in imitation of the front of a dwelling-house. Then, after passing through various stages, the full Nabataean type is reached, retaining all the native features and at the same time exhibiting characteristics which are partly Egyptian and partly Greek. Of this type there exist close parallels in the tomb-towers at el-I~ejr in north Arabia, which bear long Nabataean inscriptions and supply a date for the corresponding monuments at Petra. Then comes a series of tombfronts which terminate in a semicircular arch, a feature derived from north Syria. Finally come the elaborate facades copied from the front of a Roman temple; however, all traces of native style have vanished. The exact dates of the stages in this development cannot be fixed. Strangely, few inscriptions of any length have been found at Petra, perhaps because they have perished with the stucco or cement which was used upon many of the buildings. The simple pylon-tombs which belong to the pre-Hellenic age serve as evidence for the earliest period. It is not known how far back in this stage the Nabataean settlement goes, but it does not go back farther than the sixth century B.C.E.

A period follows in which the dominant civilization combines Greek, Egyptian and Syrian elements, clearly pointing to the age of the Ptolemies. Towards the close of the second century B.C.E., when the Ptolemaic and Seleucid kingdoms were equally depressed, the Nabataean kingdom came to the front. Under Aretas III Philhellene, (c. 85â60 B.C.E.), the royal coins begin. The theater was probably excavated at that time, and Petra must have assumed the aspect of a Hellenistic city. In the reign of Aretas IV Philopatris, (9 B.C.E.â 40 C.E.), the fine tombs of the el-I~ejr type may be dated, and perhaps also the great High-place.

Roman rule

In 106, when Cornelius Palma was governor of Syria, that part of Arabia under the rule of Petra was absorbed into the Roman Empire as part of Arabia Petraea, becoming capital. The native dynasty came to an end. But the city continued to flourish. A century later, in the time of Alexander Severus, when the city was at the height of its splendor, the issue of coinage comes to an end. There is no more building of sumptuous tombs, owing apparently to some sudden catastrophe, such as an invasion by the neo-Persian power under the Sassanid Empire. Meanwhile, as Palmyra (fl. 130â270) grew in importance and attracted the Arabian trade away from Petra, the latter declined. It seems, however, to have lingered on as a religious center. Epiphanius of Salamis (c.315â403) writes that in his time a feast was held there on December 25 in honor of the virgin Chaabou and her offspring Dushara (Haer. 51).

Religion

The Nabataeans worshipped the Arab gods and goddesses of the pre-Islamic times as well their own deified kings. The most famous of these was Obodas I, who was deified after his death. Dushara was the main male god accompanied by his female trinity: Uzza, Allat and Manah. Many statues carved in the rock depict these gods and goddesses.

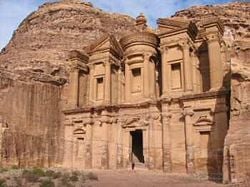

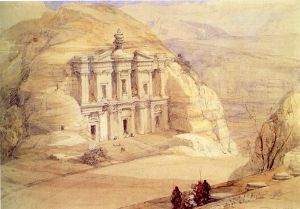

The Monastery, Petra's largest monument, dates from the first century B.C.E. It was dedicated to Obodas I and is believed to be the symposium of Obodas the god. This information is inscribed on the ruins of the Monastery (the name is the translation of the Arabic "Ad-Deir").

Christianity found its way into Petra in the fourth century C.E., nearly 500 years after the establishment of Petra as a trade center. Athanasius mentions a bishop of Petra (Anhioch. 10) named Asterius. At least one of the tombs (the "tomb with the urn") was used as a church. An inscription in red paint records its consecration "in the time of the most holy bishop Jason" (447). The Christianity of Petra, as of north Arabia, was swept away by the Islamic conquest of 629â632. During the First Crusade Petra was occupied by Baldwin I of the Kingdom of Jerusalem and formed the second fief of the barony of Al Karak (in the lordship of Oultrejordain) with the title Château de la Valée de Moyse or Sela. It remained in the hands of the Franks until 1189. It is still a titular see of the Roman Catholic Church.[9]

According to Arab tradition, Petra is the spot where Moses struck a rock with his staff and water came forth, and where Moses' brother, Aaron, is buried, at Mount Hor, known today as Jabal Haroun or Mount Aaron. The Wadi Musa or "Wadi of Moses" is the Arab name for the narrow valley at the head of which Petra is sited. A mountaintop shrine of Moses' sister Miriam was still shown to pilgrims at the time of Jerome in the fourth century, but its location has not been identified since.[10]

Decline

Petra declined rapidly under Roman rule, in large part due to the revision of sea-based trade routes. In 363 an earthquake destroyed many buildings, and crippled the vital water management system.[11]The elaborate water system supported possibly up to 20,000 people at the city's height, giving life to gardens, animals and a rich urban culture. A desert city could not survive once its water system was destroyed.

The ruins of Petra were an object of curiosity in the Middle Ages and were visited by the Sultan Baibars of Egypt in the late 1200s. For centuries the ancient ruins were known only to local Bedouins and Arab tradesmen.

The first European to describe them was the Swiss-born, Cambridge-educated linguist and explorer Johann Ludwig Burckhardt in 1812. Burckhardt was a convert to Islam who had heard locals speaking of a "lost city" hidden in the mountains of Wadi Mousa. Disguised as a pilgrim, he was able to enter the legendary city.[12] He published an account of it in his book, Travels in Syria and the Holy Land.

Site description

Petra's entrance is just past the town of Wadi Mousa. The al-Siq is the main entrance to the ancient city. The dim, narrow gorge - in some points no more than 3Â metres (9.8Â ft) wide - winds its way approximately 1Â mile (1.6Â km) and ends at Petra's most elaborate ruin, Al Khazneh (The Treasury).

Prior to reaching the Siq are three square free-standing tombs. Slightly further stands the Obelisk Tomb, which once stood 7Â metres (23Â ft) high. Nearer the Siq are rock-cut channels which once contained ceramic pipes, bringing waters of Ein Mousa to the inner city as well as to the surrounding farm country.

The path narrows to about 5Â metres (16Â ft) at the entrance to the Siq, and the walls tower over 200Â metres (660Â ft) overhead. The original ceremonial arch that once topped the walls collapsed in the late ninth century. The Siq winds for about 1.5Â kilometers (0.93Â mi) before opening to the most impressive of all Petraâs monuments - the al-Khazneh ("the Treasury"). The structure is carved from solid rock from the side of a mountain, and stands over 40Â metres (130Â ft) high. Originally a royal tomb, the Treasury takes its name from the legend that pirates hid their treasure there, in a giant stone urn which stands in the center of the second level. Barely distinguishable reliefs decorate the outside of the Khazneh, believed to represent various gods. The Treasury's age is estimated from between 100 B.C.E. to 200 C.E.

As the Siq leads into the inner city, the number of niches and tombs increases, becoming what is described as a virtual graveyard in rock.

The next site is an 8000-seat Amphitheater. Once believed to have been built by the Romans after their defeat of the Nabateans in 106 C.E., recent evidence points to construction by the Nabateans a century before. In recent years a marble Hercules was discovered under the stage floor.

The main city area follows the amphitheater, and covers about 3 square kilometers (1.2 sq mi). This basin is walled in on its eastern side by the sandstone mountain of Jabal Khubtha. The mountain had been developed with elaborate staircases, cisterns, sanctuaries, and tombs. There are three royal tombs: the Urn Tomb (once used as a church in Byzantine times); the Corinthian Tomb (a replica of Neroâs Golden Palace in Rome); and, the Palace Tomb (a three-story imitation of a Roman palace and one of the largest monuments in Petra). Nearby is the Mausoleum of Sextus Florentinius, a Roman administrator under Emperor Hadrian.

The main street was lined with columns, with markets and residences branching off to the sides, up the slopes of hills on either side.

Along the colonnaded street was a public fountain, the triple-arched Temenos Gateway (Triumphal Arch), and the Temple of the Winged Lions. Following this is an immense Byzantine Church rich with remarkably well-preserved mosaics. In December 1993, a cache of 152 papyrus scrolls in Byzantine Greek and possibly late Arabic were uncovered at the site. These scrolls are still in the process of being deciphered.

Through the Temenos Gateway is the piazza of the Qasr bint al-Faroun ("Palace of the Pharoahâs Daughter"). Dating from around 30 B.C.E., it is believed to have been the main place of worship in Nabatean Petra, and was the city's only freestanding structure. It was in use until the Roman annexation, when it was burned. Earthquakes in the fourth and eighth centuries destroyed the remainder of the building, leaving only its foundations.

There are a number of high places within Petra, requiring a climb to reach. These include:

- Umm al-Biyara, believed to be the biblical precipice of Sela.

- The top of Mount Hor and Aaronâs Tomb (Jabal Haroun).

- The Citadel (Crusador Castle), on top of al-Habis.

- al-Deir ("The Monastery"), one of Petra's most spectacular constructions. Similar to, but much larger than, the Khazneh. It receives its name from crosses on the inside walls that suggest it was once as a church.

- The High Place of Sacrifice. This contains altars cut into the rock, along with obelisks and the remains of buildings used to house the priests. There are two large depressions with drains that show where the blood of sacrificial animals flowed out.

- The Lion Fountain. Evidence points to this having had a religious function.

- The Garden Tomb, which archaeologists believe was more likely a temple.

- The Tomb of the Roman Soldier and the Triclinium (Feast Hall), which has the only decorated interior in Petra.

Petra today

On December 6, 1985, Petra was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site based upon its outstanding cultural value. Its varied architectural monuments dating from prehistoric to medieval times are in a relatively good state of preservation, though its listing on UNESCO will provide further protection.

In 1988 the Jordanian government amended its Antiquities Act by enacting Law no.21. The new law defined antiquities as "any movable or immovable object constructed, made, inscribed, built, discovered or modified by man prior to 1700 C.E., including caverns, sculptures, coined articles, pottery, manuscripts and all articles related to the birth and development of sciences, arts, crafts, religions and traditions of past civilizations, or any part thereto added or reconstructed following that date."[13] This brought Petra under its jurisdiction, allowing it further protection.

On July 7, 2007, Petra was named one of the New Seven Wonders of the World. The designation of new wonders of the world was organized by New Open World Foundation, based upon votes cast from ordinary citizens throughout the world. The purpose is to undertake the task of documentation and conservation of works of monuments worldwide, recognizing the importance of the world's heritage to its future.[14]

Notes

- â Dead Sea Scroll 4Q462

- â Eusebius (Onom. sacr. 286, 71. 145, 9; 228, 55. 287, 94)

- â Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews. (iv. 7, 1~ 4, 7)

- â Nabataea.net. Petra: Water Works Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- â Naomi Lubick, GeoTimes (June 2004), A New Look at Petra American Geological Institute. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- â

- 25. Mithcah - Nu. 33:28-29 associated with Petra on the borders of Moab and Edom near Petra.

- 26. Hashmonah - Nu. 33:29-30 Ha Shmona Kiryat Shmona South

- 27. Moseroth - Nu. 33:30-31 described as the place where Aaron died at the foot of Mount Hor (Petra)

- 28. Bene-Jaakan - Nu. 33:31-32 the wells of Jaakan Near Mount Hor (Petra)

- 29. Petra - Nu. 33:32-33 Siq The cleft of the mountain, the entrance to Petra

- â Genesis xiv. 6, xxxvi. 20â30; Deut. ii. 12.

- â Judges i. 36; Isaiah xvi. i, xlii. 11; Obad. 3.

- â S. Vailhé, Catholic Encyclopedia. 1913. Petra Retrieved January 15, 2009.

- â Martin Gray. Petra Jordan Places of Peace and Power. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- â Grace Glueck, October 17, 2003, ART REVIEW; Rose-Red City Carved From the Rock New York Times. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- â The Royal Hashemite Court. Petra Retrieved January 15, 2009.

- â Government of Jordan. Department of Antiquities - General Information Retrieved January 15, 2009.

- â NewOpenWorld Foundation. The Official New 7 Wonders of the Modern World Retrieved January 15, 2009.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bedal, Leigh-Ann. 2004. The Petra pool-complex: a Hellenistic paradeisos in the Nabataean capital: (results from the Petra "Lower Market" survey and excavation, 1998). Piscataway, NJ, USA: Gorgias Press. ISBN 1593331207.

- Go 2 Petra. Petra Guide.

- Harty, Rosemary, 2006, The Bedouin Tribes of Petra. The Digital Journalist. Retrieved May 10, 2008.

- Hill, John E., 2004. "The Peoples of the West" from the Weilue, by Yu Huan. A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265 C.E., Published in 429 C.E. Retrieved January 24, 2009.

- Reid, Sara Karz. 2005. The small temple: a Roman imperial cult building in Petra, Jordan. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. ISBN 1593333390.

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Petra Retrieved January 11, 2009.

External links

All links retrieved November 23, 2022.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.