The Powhatan (also spelled Powatan and Powhaten), or Powhatan Renape (literally, the "Powhatan Human Beings"), is the name of a Native American tribe, and also the name of a powerful confederacy of tribes that they dominated. Also known as Virginia Algonquians, they spoke an eastern-Algonquian language, and lived in what is now the eastern part of Virginia at the time of the first European-Native encounters there. The name is believed to have originated from a village near the head of navigation on a major river.

The Powhatan are significant to American history because of their early contact with American settlers and adaptable forms of self preservation. It was Powhatan, specifically Pamunkey, that the first permanent English colonists at Jamestown met. Wahunsunacock (who has become better-known as Chief Powhatan) and his daughter Pocahontas were from the Pamunkey tribe. This tribe has been in existence since pre-Columbian times. It is one of the two currently existing tribes that were part of the Powhatan Confederacy. The Pamunkey reservation is currently located on the site of some of its ancestral land on the Pamunkey River adjacent to King William County, Virginia.

Name

The name Powhatan is believed to have originated as the name of the village or "town" Wahunsunacock (who has become better-known as Chief Powhatan) was from. It was located in the East End portion of the modern-day city of Richmond, Virginia). "Powhatan" was also the name used by the natives to refer to the river where the town sat at the head of navigation (today called the James River, renamed by the English colonists for their own king, James I).

"Powhatan" is an Virginia Algonquian word meaning "at the waterfalls"; the settlement of Powhatan was at the falls of the James River.[1][2]

Today, the term "Powhatan" is taken to refer to their political identity, while "Renape" which means "human beings," refers to their ethnic/language identity.[3]

History

Building the Powhatan Confederacy

The original six constituent tribes in Wahunsunacock's Powhatan Confederacy were: the Powhatans proper, the Arrohatecks, the Appamattucks, the Pamunkeys, the Mattaponis, and the Chiskiacks. He added the Kecoughtans to his fold by 1598. Another closely related tribe in the midst of these others, all speaking the same language, was the Chickahominy, who managed to preserve their autonomy from the confederacy.

Wahunsunacock had inherited control over just four tribes, but dominated over 30 by the time the English settlers established their Virginia Colony at Jamestown in 1607.

Besides the capital village of "Powhatan" in the Powhatan Hill section of the eastern part of the current city of Richmond, another capital of this confederacy about 75 miles to the east was called Werowocomoco. It was located near the north bank of the York River in present-day Gloucester County. Werowocomoco was described by the English colonists as only 12 miles as the crow flies from Jamestown, but also described as 25 miles downstream from present-day West Point, Virginia.

Around 1609, Wahunsunacock shifted his capital from Werowocomoco to Orapakes, located in a swamp at the head of the Chickahominy River. Sometime between 1611 and 1614, he moved further north to Matchut, in present-day King William County on the north bank of the Pamunkey River, not far from where his brother Opechancanough ruled at Youghtanund.

English settlers in the land of the Powhatan

Captain Christopher Newport led the first English exploration party up the James River in 1607 and first met Chief Wahunsunacock, whom they called Chief Powhatan, and several of his sons. The settlers had hoped for friendly relations and had planned to trade with the Native Americans for food. Newport later crowned the Chief with a ceremonial crown and presented him with many European gifts to gain the Indians' friendship, realizing that Chief Powhatan's friendship was crucial to the survival of the small Jamestown colony.

On a hunting and trade mission on the Chickahominy River, President of the Colony Captain John Smith was captured by Opechancanough, the younger brother of Chief Powhatan. According to Smith's account (which in the late 1800s was considered to be fabricated, but is still believed by some to be mostly accurate although several highly romanticized popular versions cloud the matter), Pocahontas, Powhatan's daughter, prevented her father from executing Smith. Some researchers have asserted that this was a ritual intended to adopt Smith into the tribe, but other modern writers dispute this interpretation, pointing out that nothing is known of seventeenth century Powhatan adoption ceremonies, and that this sort of ritual is even different from known rites of passage. Further, these writers argue, Smith was not apparently treated as a member of the Powhatans after this ritual.

In fact, some time after his release, Smith went with a band of his men to Opechancanough's camp under pretense of buying corn, seized Opechancanough by the hair, and at the point of a pistol marched him off a prisoner. The Pamunkey brought boat-loads of provisions to ransom their chief's brother, who thereafter entertained more respect and deeper hatred for the English.[4]

John Smith left Virginia for England, in 1609, because of serious burn injuries sustained in a gunpowder accident (never to return). In September 1609, Captain John Ratcliffe was invited to Orapakes, Powhatan's new capital. When he sailed up the Pamunkey River to trade there, a fight broke out between the colonists and the Powhatans. All of the English were killed, including Ratcliffe, who was tortured by the women of the tribe.

During the next year, the tribe attacked and killed many Jamestown residents. The residents fought back, but only killed 20. However, the arrival at Jamestown of a new Governor, Thomas West, 3rd Baron De La Warr, (Lord Delaware) in June of 1610 signaled the beginning of the First Anglo-Powhatan War. A brief period of peace only came after the marriage of Pocahontas and colonist John Rolfe in 1614. However, within a few years both the Chief and Pocahontas were dead from disease. The Chief died in Virginia, but Pocahontas died in England, having traveled willingly there with John Rolfe. Meanwhile, the English settlers continued to encroach on Powhatan territory.

After Wahunsunacock's death, his younger brother, Opitchapam, became chief, followed by their younger brother Opechancanough, who in 1622 and 1644 attempted to force the English from Powhatan territories. These attempts saw strong reprisals from the English, ultimately resulting in the near destruction of the tribe. During the 1644 incident, Royal Governor of Virginia William Berkeley's forces captured Opechancanough. While a prisoner, Opechancanough was killed by a soldier (shot in the back) assigned to guard him. He was succeeded as Weroance by Nectowance and then by Totopotomoi and later by his daughter Cockacoeske. By 1665, the Powhatan were subject to stringent laws enacted that year, which compelled them to accept chiefs appointed by the governor.

The Virginia Colony continued to grow and encroach on Indian land making it impossible to sustain their traditional lifestyle. Many Pamunkeys were forced to work for the English or were enslaved. As the settlement grew so did their fear of Native Americans and subsequent racist tendencies and anger. This culminated in Bacon's Rebellion which began in 1675 as the colonists and Royal Governor William Berkeley disagreed about the handling of conflicts with the Indians. During the subsequent reprisals for an incident which took place in what is currently Fairfax County, the Pamunkeys were among many other innocent tribes which were wrongfully targeted. These themes of militancy and encroachment continued throughout much of American history. Although the tribe was divided in the eighteenth century, many Powhatan tribes including the Pamunkey secretly kept their identity. After the Treaty of Albany in 1684, the Powhatan Confederacy all but vanished.

Culture

The Powhatan lived east of the fall line in Tidewater Virginia. Their houses were made of poles, rushes, and bark, and they supported themselves primarily by growing crops, especially maize, but also by some fishing and hunting. Villages consisted of a number of related families organized in tribes that were led by a king or queen, who was a client of the Emperor and a member of his council.

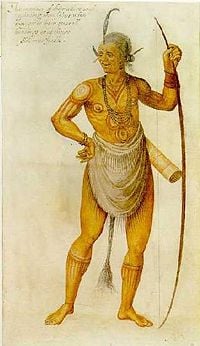

According to research by the National Park Service, Powhatan

men were warriors and hunters, while women were gardeners and gatherers. The English described the men, who ran and walked extensively through the woods in pursuit of enemies or game, as tall and lean and possessed of handsome physiques. The women were shorter, and were strong because of the hours they spent tending crops, pounding corn into meal, gathering nuts, and performing other domestic chores. When the men undertook extended hunts, the women went ahead of them to construct hunting camps. The Powhatan domestic economy depended on the labor of both sexes.[5]

Pamunkey

The Pamunkeys were the largest and most powerful tribe of the Powhatan Confederacy. Both Chief Powhatan himself and his famous daughter Pocahontas were Pamunkeys.

The traditional Pamunkey way of life is a subsistence lifestyle. They have always lived through a combination of fishing, trapping, hunting, and subsistence farming. The Pamunkey River was a main mode of transportation and food source. It also provided accessibility to hunting grounds, other tribes, and a defensive view of local river traffic. Access to the river was crucial because Pamunkey villages were not permanent settlements. Because they did not use fertilizer, fields and homes were moved about every ten years. Permitted use of unoccupied land was open to anyone, but understood as under Pamunkey jurisdiction. This proved a major source of conflict with the English because it was the antithesis of their land ownership model.

Coined by the English as ‚Äúlonghouses,‚ÄĚ Pamunkey structures tended to be long and narrow. They were relatively simple structures made out of bent saplings and covered with woven mats. Homes of families of higher status were also made of bark. By changing the strength of indoor fires and the amount of mats or bark, these houses were adaptable to all weather conditions and comfortable.

The tribe was governed by a weroance (Chief) and a tribal council composed of seven members, elected every four years. An ethnology written in 1894 by Garland Pollard, on behalf of the Smithsonian Institute Bureau of Ethnology, stated

The council names two candidates to be voted for. Those favoring the election of candidate number 1 must indicate their choice by depositing a grain of corn in the ballot-box at the schoolhouse, while those who favor the election of candidate number 2 must deposit a bean in the same place. The former or the latter candidate is declared chosen according as the grains of corn of the beans predominate.

Typical laws are mostly concerned with but not limited to intermarriage, preventing slander, bad behavior, and land use. There are no corporal punishments such as incarcerations or chastisement. Rather, punishments are only in terms of fines or banishment (usually after the third offense).

A piece of the Pamunkey story is often told through Pocahontas, but from an English perspective. When comparing primary documents from the time of English arrival, it is apparent that initial contact was characterized by mutual cultural misunderstanding. Primary documentation characterizes the Virginia Indians through a series of paradoxes. It is apparent that there is great respect for Chief Powhatan but the other Indians are repeatedly called variations of devils and savages, such as ‚Äúnaked devils‚ÄĚ or they were standing there ‚Äúgrim as devils.‚ÄĚ There is a great fear and appreciation coupled with distrust and uneasiness. The following quotation from John Smith‚Äôs diary exemplifies this duality.

It pleased God, after a while, to send those people which were our mortal enemies to relieve us with victuals, as bread, corn fish, and flesh in great plenty, which was the setting up of our feeble men, otherwise we had all perished.[6]

Smith makes it apparent that without Chief Powhatan’s kindness the colony would have starved. However, Smith still considers Chief Powhatan’s people his enemies.

This general distrust from the English permeated throughout many tribes, but a sense of honor and morality is attached to the Pamunkey. ‚ÄúTheir custom is to take anything they can seize off; only the people of Pamunkey we have not found stealing, but what others can steal, their king receiveth‚ÄĚ (83). Even though it is apparent that the Pamunkeys meant no harm until they were pushed to seek revenge, they were repeatedly wronged.

Chief Powhatan could not understand the English need to claim everything and their overall mindset:

What it will avail you to take by force you may quickly have by love, or to destroy them that provide you food? What can you get by war, when we can hide our provisions and fly to the woods? Whereby you must famish by wronging us your friends. And why are you thus jealous of our loves seeing us unarmed, and both do, and are willing still to feed you, with that you cannot get but by our labors?[6]

This question posed by Chief Powhatan was translated in Smith’s writings. He could not understand why the British would want to taint relations with his tribe. They were providing Jamestown with food, since the colonists refused to work, and could not otherwise survive the winter. It is apparent that these Pamunkeys only went to war as a last resort. They did not understand why the only tactics of the British were force and domination.

Contemporary Powhatan

Remaining descendants in Virginia in the twenty-first century include seven recognized tribes with ties to the original confederacy, including two with reservations, the Pamunkey and the Mattaponi, which are accessed through King William County, Virginia.[7] Many years after the Powhatan Confederacy no longer existed, and some miles to the west of area it included, Powhatan County in the Virginia Colony was named in honor of Chief Wahunsunacock, who was the father of Pocahontas.

Although the cultures of the Powhatan and the European settlers were very different, through the union of Pocahontas and English settler John Rolfe and their son Thomas Rolfe, many descendants of the First Families of Virginia trace both Native American and European roots.

Approximately 3,000 Powhatan people remain in Virginia. Some of them live today on two tiny reservations, Mattaponi and Pamunkey, found in King William County, Virginia. However, the Powhatan language is now extinct. Attempts have been made to reconstruct the vocabulary of the language; the only sources are word lists provided by Smith and by William Strachey.

Powhatan County was named in honor of the Chief and his tribe, although located about 60 miles to the west of lands ever under their control. In the independent city of Richmond, Powhatan Hill in the city's east end is traditionally believed to be located near the village Chief Powhatan was originally from, although the specific location of the site is unknown.

There is also a small community of the Powhatan Renape Nation in New Jersey. They live in 350 acres of state owned land in the town of Westampton, where one by one, they came to settle a tiny subdivision known as Morrisville and Delair in Pennsauken Township. Their current property is recognized by the state of New Jersey and the general public as the Rankokus Indian Reservation. The Nation has an administrative Center located that manages its community, educational, cultural, social and other programs and services. Thousands of school children visit the Reservation annually to tour its museum, art gallery, and the many exhibits and nature trails on the grounds.

The Pamunkeys have been able to survive because of their remarkable ability to adapt as a tribe. In modern times they have changed their interpretation of living off the land, but still uphold the central value of subsistence living. They continue to hunt, trap, and fish on what is left of their reservation grounds. In order to supplement these activities they have turned traditional tribal pottery into profit generating ventures, while continuing to rely on their natural environment. Their pottery is made from all natural clay including pulverized white shells used by their ancestors.

The Pamunkey Indian Museum was built in King William County, Virginia in 1979 to resemble a traditional Native American long house. Located on the reservation, it provides visitors with an innovative approach to the tribe throughout the years through artifacts, replicas, and stories. The Smithsonian Institution selected the Pamunkeys as one of 24 tribes to be featured in the National Museum of the American Indian.

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ Carl Waldman, Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes (Checkmark Books, 2006, ISBN 978-0816062744).

- ‚ÜĎ William Bright, Native American Place Names of the United States (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2004), 397.

- ‚ÜĎ Powhatan History.www.powhatan.org. Retrieved October 8, 2007.

- ‚ÜĎ Powhatan Indian Chiefs and Leaders Retrieved October 8, 2007.

- ‚ÜĎ Excerpt from the National Park Service Approved Statement of Significance for the Proposed Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Water Trail.www.johnsmith400.org.

- ‚ÜĎ 6.0 6.1 Ed Southern, The Jamestown Adventure: Accounts of the Virginia Colony, 1605-1614. (Winston-Salem, NC: John F. Blair, 2004)

- ‚ÜĎ Matchut.www.virginiaplaces.org. Retrieved October 8, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Barbour, Philip. Pocahontas and her World: A chronicle of America's first settlement in which is related the story of the Indians and the Englishmen, particularly Captain John Smith, Captain Samuel Argall, and Master John Rolfe. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1969. ISBN 039507391X

- Bright, William. Native American Place Names of the United States. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0806135984

- Custalow, Linwood, and Angela L. Daniel. The True Story of Pocahontas: The Other Side of History. Golden, CO: Fulcrum Publishing, 2007. ISBN 1555916325

- Hatfield, April Lee. Atlantic, Virginia: Intercolonial Relations in the Seventeenth Century. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004. ISBN 0812237579

- Nichols, A. Bryant Jr. Captain Christopher Newport: Admiral of Virginia. Sea Venture, LLC., 2007. ISBN 0615140017

- Pollard, John Garland. The Pamunkey Indians Of Virginia (1894). Kessinger Publishing, LLC., 2008. ISBN 978-0548890332

- Rountree, Helen C. Pocahontas, Powhatan, Opechancanough: Three Indian Lives Changed By Jamestown. University of Virginia Press, 2005. ISBN 0813925967

- Rountree, Helen C. The Powhatan Indians of Virginia: Their Traditional Culture. (Civilization of the American Indian Series) Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1992. ISBN 0806124555

- Southern, Ed. The Jamestown Adventure: Accounts of the Virginia Colony, 1605-1614. Winston-Salem, NC: John F. Blair, 2004. ISBN 978-0895873026

- Waldman, Carl. Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes. New York, NY: Checkmark Books, 2006. ISBN 978-0816062744

External links

All links retrieved November 30, 2022.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.