| Saint Benedict | |

|---|---|

Saint Benedict and his Rule | |

| Abbot Patron of Europe | |

| Born | c. 480 in Norcia (Umbria, Italy) |

| Died | c. 547 in Monte Cassino |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church Anglican Communion Eastern Orthodox Church Lutheran Church |

| Canonized | 1220 |

| Major shrine | Monte Cassino Abbey;

Saint-Benoît-sur-Loire, near Orléans, France; Sacro Speco, at Subiaco, Italy |

| Feast | Western Christianity: 11 July (in pre-1969 calendars, 21 March) Byzantine Rite: 14 March |

| Attributes | -Bell, broken cup with serpent representing poison, bush, crosier, Benedictine cowl, copy of his Rule, rod of discipline, raven |

| Patronage | -Against poison, against witchcraft, of agricultural workers, civil engineers, coppersmiths, dying people, Europe, farmers, fever, various other disease, Italian architects, Norcia (Italy), people in religious orders, Schoolchildren, servants who have broken their master's belongings, spelunkers, against temptations. |

Saint Benedict of Nursia (c. 480 – c. 547) was a major Christian saint from Italy, whose famous monastic Rule was adopted throughout the Western monastic tradition in the Middle Ages.

After spending his childhood in Rome and then devoting himself to a period as a solitary monk, Benedict founded 12 monastic communities, the best known being Monte Cassino in the mountains of southern Italy. He became legendary for his personal asceticism and for performing numerous miracles. His greatest achievement, however, was his Rule, containing detailed containing precepts for his monks and the administration of his communities. Its unique spirit of moderation and reasonableness influenced most European religious communities to adopt it, making Benedict one of the most influential Christian writers in history. He is often called the founder of western Christian monasticism.

However, Benedict did not found a distinct religious order. Although many important religious communities in history are commonly referred to as Benedictine, the formal Order of St. Benedict (OSB) is of modern origin.

Saint Benedict was named the patron protector of Europe by Pope Paul VI in 1964. His feast day is celebrated on July 11.

Biography

The only authentic ancient account of Benedict is found in the second volume of Pope Gregory I's four-book Dialogues, written in 593. Gregory's account was based on traditions he received from Benedict's followers: Honoratus, abbot of the monastery at Subiaco, and Constantinus, Benedict's disciple and successor as abbot of Monte Cassino. It is not a biography in the modern sense of the word, but is rather a hagiography. It provides a spiritual portrait of the gentle, disciplined abbot, consisting, for the most part, of a number of miraculous incidents which give little help toward constructing an objective chronological account of his career.

Early life

Benedict was the son of a Roman noble of Nursia (modern Norcia), in Umbria, central Italy. A tradition related by the English writer Bede (673–735) says that Benedict was a twin, with his sister being a woman named Scholastica. His boyhood was spent in Rome, where he lived with his parents and attended school until he reached his higher studies.

Then, according the Gregory's account, "giving over his books, and forsaking his father's house and wealth, with a mind only to serve God, he sought for some place where he might attain to the desire of his holy purpose." His exact age at the time is a matter of debate, generally presumed to be between the ages 14 and 20.

Benedict does not seem to have left Rome with the intention of becoming a hermit. He took his old nurse with him as a servant and they settled down to live in Enfide, near a church dedicated to St Peter, in some kind of association with "a company of virtuous men" who were in sympathy with his spiritual feelings. Enfide is traditionally identified with the modern Affile in the Simbruini mountains, about 40 miles east of Rome and two from Subiaco.

A short distance from Enfide is the entrance to a narrow, gloomy valley, penetrating the mountains. The ravine soon reaches the site of a former villa of the emperor Nero. Nearby were the ruins of certain Roman baths, of which a few great arches still stand. A nearby cave about ten feet deep with a large triangular-shaped opening is believed to have served as Benedict's cell. Below, after a rapid descent, lay the blue waters of a lake.

Near Enfide, Benedict met a monk, Romanus of Subiaco, whose monastery was on the mountain above the cliff overhanging the cave. Romanus discussed with Benedict the purpose which had brought him to the area, and gave him the monk's habit. On Romanus' advice, Benedict became a hermit and remained in seclusion for three years in his cave. During this time, Romanus brought him food, which he lowered into the cave by means of a rope from the ledge above.

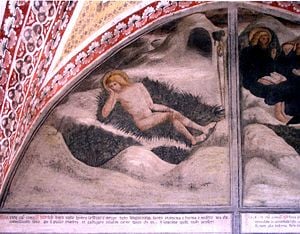

Pope Gregory reports several episodes from Benedict's life as an anchorite (solitary) monk. Early in Benedict's isolation, certain local shepherds saw him, at first confusing him for a wild animal due to his wearing clothing made of skins. Several of them were converted through their conversations with him. Attacked by a small black bird, Benedict defeated it by the sign of the Cross. Soon, however, he faced a far greater temptation, in the form of the memory of a beautiful woman he had previously known. So great was the lust kindled by this recollection that he almost abandoned his vocation. To deal with the temptation, he tortured his body by wallowing naked in brambles, badly tearing his skin but healing his soul. He later told his disciples that after this, he was never again sexually tempted.

Benedict the abbot

Through his time as a hermit, Benedict matured both in mind and character. His life of discipline and solitude also won him the respect of local Christians.

On the death of the abbot of a monastery in the neighborhood, identified by some as Vicovaro, the monks came to him and invited him to become their new abbot. Benedict knew too well the lax discipline of the monastery. He felt that their manners were different from his and therefore they would never agree together. However, he finally acceded to their wishes. The experiment failed badly, so much so that the monks eventually tried to poison him. The legend goes that they attempted to do away with him by poisoning his drink. However, when he prayed a blessing over the cup, it miraculously shattered. He then returned to his cave.

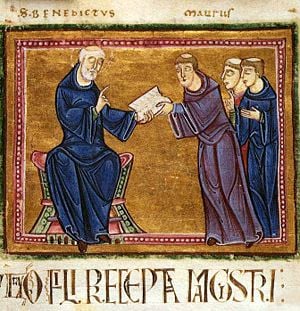

However, many people, attracted by Benedict's sanctity and character, came to Subiaco to seek his guidance and learn the true way of monastic life. Over the succeeding years, he caused 12 monasteries to be constructed in the valley, in each of which he placed a superior with 12 monks. In a 13th, he himself lived with "a few, such as he thought would more profit and be better instructed by his own presence." He remained the abbot of all 13 cloisters also creating several schools for children in association with his communities. Among the first to be raised under his care were the future saints Maurus and Placidus. From this time on, his miracles are said to have become increasingly frequent.

Among the legends associated with this period is a story of Benedict miraculously discovering a hidden fountain high on a mountain, giving the monks who lived there a convenient source of water. Like the prophet Elisha (2 Kings 6:1-7), he caused an iron axe-head, which had been lost in the water, to float. When the young monk Placidus fell into the lake and was about to drown, Benedict sensed the danger while still in his cell. He commanded Maurus to aid his companion, and Maurus was miraculously empowered to walk on the water to effect Placidus' rescue.

Jealous monks of a rival monastery tried to poison Benedict's bread. This time, when he blessed the bread, a raven swept in and took the loaf away. Benedict is also said to have torn down the altar and idol of Apollo in the town of Monte Cassino, converting many of the locals and establishing the foundation for the later famous abbey there. When a child monk was crushed to death while building a wall, Benedict raised him from the dead, healing his utterly destroyed body and setting him immediately back to his work.

Benedict's prophetic powers were also legendary. He predicted the death of Totila, king of the Goths, and knew before the fact that the Lombards would close one of the abbeys he had established. He was also given knowledge of the secret sins of the monks and nuns under his care.

Benedict spent the final years of his life seeking to realize the ideal of monasticism in a communal setting. To create unity and formalize discipline, he drew up his famous Rule. He died at Monte Cassino on March 21, 547, aged 67.

The Benedictine Rule

A work of 73 short chapters, the Rule of Saint Benedict presents both spiritual guidance concerning how to live a life on earth centered on Christ and administrative guidelines on how to run a monastery efficiently. Not an entirely original document, it is believed to be heavily influenced by the writings of the Eastern monastic writer John Cassian. Nevertheless, it is unique in its comprehensiveness, balance, and relative moderation.

More than half the chapters describe specific rules for community members and the qualities of obedience and humility expected of monks. About one-fourth regulate worship. One-tenth outlines how, and by whom, the monastery should be managed, and another tenth specifically describes the abbot’s pastoral duties. Considered in its time to be a moderate tradition representing a middle path between laxity and overly-strict asceticism, it nevertheless strikes modern readers as highly disciplined in its approach. It is summarized as follows:

Benedict begins by describing four kinds of monks: 1) Cenobites, who live together in a monastery; 2) Anchorites, or hermits; 3) "Sarabaites," living by twos and threes together with no rule or superior; and 4) "Gyrovagues," who wander from one monastery to another. It is for the cenobites that Benedict's Rule is written (chapter 1). He describes the necessary qualifications of an abbot and forbids him to make distinctions between persons in the monastery except on the basis of merit. He ordains that members of the community shall be brought together in a council regarding matters of importance (2-3).

Benedict lists 73 "tools of the spiritual craft," constituting the duties of every Christian and demands absolute obedience to the superior in all his lawful commands. While stopping short of ordaining a rule of silence, he advises moderation in the use of speech. He describes 12 steps of humility as a ladder that leads to heaven. He divides the day into the eight canonical hours and provides detailed regulation for communal prayers (4-20).

A dean is to be appointed over every ten monks (21). Each monk is to have a separate bed and is to sleep in his habit. Benedict specifies a graduated scale of punishments for various sins: private admonition, public reproof, separation from the community at meals and other group meetings, corporal punishment, and/or finally excommunication. Officials are to be appointed to oversee the material goods of the monastery, and no private possessions are allowed without the permission of the abbot. Monks are to take turns serving in the kitchen. Children, as well as the sick and the elderly, are to have certain dispensations from the strict Rule (21-37).

Scriptures are to be read aloud during meals, during which time verbal silence is to be observed by all except the reader. Two cooked meals are to be provided each day, along with a pound of bread and a half a pint of wine for each monk. Meat, however, is prohibited except for the sick and the weak. An edifying book is to be read in the evening, and there is to be strict silence after Compline, the day's final communal gathering (38-47).

At least five hours of manual labor are to be done each day. Rules are given for monks working in the fields or traveling. Voluntary self-denial is recommended for Lent. Guests are to be shown proper hospitality. Monks may receive letters or gifts only with the abbot's permission. Clothing is to be humble but appropriate for the season. Rules are given for the admission of new members (48-61).

Abbots are to be elected by the monks. Monks are exhorted fraternal charity and mutual obedience, and are forbidden to strike each other. The Rule is not offered as an ideal of perfection, but as a path toward godliness (62-73).

Legacy

After his death, Saint Benedict became extremely influential as his Rule came to be adopted in the majority of the monasteries of Western Christendom. Indeed, the early Middle Ages have been called "the Benedictine centuries." Pope Benedict XVI, who adopted the saint's name when he became pope, stated: “With his life and work, Saint Benedict exercised a fundamental influence on the development of European civilization and culture” and helped Europe to emerge from the "dark night of history" that followed the fall of the Roman Empire.[1]

Beyond its religious influences, the Rule of Saint Benedict has been one of the most important written works in the shaping of Western society, embodying the idea of a written constitution, authority limited by law, and the right of the ruled to review the legality of the actions of their rulers. It also incorporated a degree of democracy in a non-democratic society.

Benedict himself did not establish a religious order as such, although many medieval monasteries were known as Benedictine due to their adherence to his Rule. Despite Benedict's concern that monasteries remain humble and avoid the trappings of wealth, the later Benedictine monasteries ironically acquired considerable material riches, leading to both luxury and worldliness. As a result, some Benedictines led reform movements to return to a stricter observance of both the letter and spirit of the Rule. Examples include the Camaldolese, the Cistercians, the Trappists, and the Sylvestrines.

The modern "Order of Saint Benedict" differs from other Western religious orders in that it is not a legal entity but consists of autonomous communities formed loosely into what is known as the Benedictine Confederation. In the modern confederation of the Benedictine Order, the "Black Monks" (so called because of color of their habits) were united under an abbot primate in the late nineteenth century. The primacy is centered in the International Benedictine College of Saint Anselm in Rome.

Benedict was named patron protector of Europe by Pope Paul VI in 1964. His feast day, previously March 21, was moved in 1969 to July 11, a date on which he was traditionally celebrated in many areas since the eighth century.

Saint Benedict Medal and coins

The Saint Benedict Medal originated from a cross in honor of St Benedict. Around the medal's outer margin is "Eius in obitu nostro praesentia muniamur" ("May we, at our death, be fortified by His presence"). The other side of the medal has a cross with the initials for the words "Crux Sacra Sit Mihi Lux" ("May the Holy Cross be my light") on the vertical beam and the initials for "Non Draco Sit Mihi Dux" ("Let not the dragon be my guide") on the horizontal beam. The initial letters for "Crux Sancti Patris Benedicti" ("The Cross of Our Holy Father Benedict") are on the interior angles of the cross. Around the medal's margin on this side are the initials for "Vade Retro Satana, Nunquam Suade Mihi Vana—Sunt Mala Quae Libas, Ipse Venena Bibas" ("Begone, Satan, do not suggest to me thy vanities—evil are the things thou profferest, drink thou thy own poison"). Either the inscription "Pax" (Peace) or the Christogram "IHS" is located at the top of the cross in most cases.

Legend holds that in 1647, during a witchcraft trial at Natternberg near Metten Abbey in Bavaria, several women testified that although they indeed practiced witchcraft, they had no power over Metten, because it was under the protection of the cross. An investigation found a number of painted crosses on the walls of the abbey with certain letters whose meaning had been forgotten. A manuscript written in 1415 was eventually found that had a picture of Saint Benedict holding a scroll in one hand and a staff which ended in a cross in the other. On the scroll and staff were written the full words of the initials contained on the crosses. Medals then began to be struck in Germany, which then spread throughout Europe. This medal was given papal sanction by Pope Benedict XIV in his briefs of December 23, 1741, and March 12, 1742. The current version of the Saint Benedict Medal was first struck in 1880 to commemorate the fourteenth centenary of St. Benedict's birth and is also called the Jubilee Medal.

Saint Benedict has also been the motive of many collector's coins around the world. One of the most prestigious and recent ones is the Austria 50 euro 'The Christian Religious Orders', issued in March 13, 2002.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Benedict XVI, "Saint Benedict of Norcia", Homily given to a general audience at St Peter's Square on Wednesday, April 9, 2008. Retrieved January 23, 2009.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Butcher, Carmen Acevedo. Man of Blessing: A Life of St. Benedict. Brewster, Mass: Paraclete Press, 2006. ISBN 1612611621

- Grün, Anselm. Benedict of Nursia: His Message for Today. Collegeville, Minn: Liturgical Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0814629109

- Holyhead, Verna, and Lynne Muir. The Gift of St Benedict. Mulgrave, Vic: John Garratt Publishing, 2002.

- Vogüé, Adalbert de. Saint Benedict: The Man and His Work. Petersham, MA: St. Bebe's Publications, 2006. ISBN 978-1879007482

External links

All links retrieved September 27, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.