Siege of Jerusalem (636-637)

| Siege of Jerusalem (637) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Muslim conquest of Syria (Arab–Byzantine Wars) | |||||||||

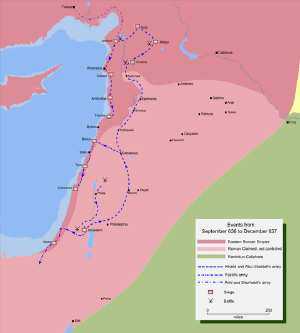

Map of the Muslim invasion of Syria and the Levant (September 636 to December 637) | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Combatants | |||||||||

| Rashidun Caliphate | Byzantine Empire | ||||||||

| Commanders | |||||||||

| Umar Ibn al-Khattab Abu Ubayda ibn al-Jarrah Khalid ibn al-Walid Yazid ibn Abi Sufyan Amr ibn al-As Shurahbil ibn Hasana Miqdad ibn Aswad 'Ubadah ibn al-Samit |

Patriarch Sophronius | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| ~20,000[1] | Unknown | ||||||||

The siege of Jerusalem (636–637) was part of the Muslim conquest of the Levant and the result of the military efforts of the Rashidun Caliphate against the Byzantine Empire in the year 636–637/38. It began when the Rashidun army, under the command of Abu Ubayda, besieged Jerusalem beginning in November 636. After six months, the Patriarch Sophronius agreed to surrender, on condition that he submit only to the Caliph. In 637 or 638, Caliph Umar (Reign 634-644) traveled to Jerusalem in person to receive the submission of the city and the Patriarch surrendered to him.

The Muslim conquest of the city solidified Arab control over Judea, which would not again be threatened until the First Crusade in 1099.

Background

Jerusalem was an important city of the Byzantine province of Palaestina Prima. Just 23 years prior to the Muslim conquest, in 614, it fell to an invading Sassanid army under Shahrbaraz during the last of the Byzantine–Sasanian Wars. The Persians looted the city, and are said to have massacred its 90,000 Christian inhabitants.[2] As part of the looting, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre was destroyed and the True Cross captured and taken to Ctesiphon as a battle-captured holy relic. The Cross was later returned to Jerusalem by Emperor Heraclius after his final victory against the Persians in 628. The Jews, who were persecuted in their Christian-controlled homeland, initially aided the Persian conquerors.[3]

After the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad in 632, Muslim leadership passed to Caliph Abu Bakr (Reign 632-634) following a series of campaigns known as the Ridda Wars. Once Abu Bakr's sovereignty over Arabia had been secured, he initiated a war of conquest in the east by invading Iraq, then a province of the Sassanid Persian Empire. While on the western front, his armies invaded the Byzantine Empire.[4]

In 634, Abu Bakr died and was succeeded by Umar (Reign 634-644), who continued his own war of conquest.[5] In May 636, Emperor Heraclius (Reign 610-641) launched a major expedition to regain the lost territory, but his army was defeated decisively at the Battle of Yarmouk in August 636. After the defeat Abu Ubayda, the Rashidun commander-in-chief of the Rashidun army in Syria, held a council of war in early October 636 to discuss future plans. Opinions of objectives varied between the coastal city of Caesarea and Jerusalem. Abu Ubayda could see the importance of both these cities, which had resisted all Muslim attempts at capture. Unable to decide the matter, he wrote to Caliph Umar for instructions. In his reply, the caliph ordered them to capture Jerusalem. Accordingly, Abu Ubayda marched towards Jerusalem from Jabiyah, with Khalid ibn al-Walid and his mobile guard leading the advance. The Muslims arrived at Jerusalem around early November, and the Byzantine garrison withdrew into the fortified city.[1]

Siege

Jerusalem had been well-fortified after Heraclius recaptured it from the Persians.[6] After the Byzantine defeat at Yarmouk, Sophronius, the Patriarch of Jerusalem, repaired its defenses.[7] The Muslims had not attempted any siege of the city previously. However, since 634, Saracen forces had the potential to threaten all routes to the city. Although it was not encircled, it had been in a state of siege since the Muslims captured the towns of Pella and Bosra east of the Jordan River. After the Battle of Yarmouk, the city was severed from the rest of Syria, preparing it for a siege that seemed inevitable.[6] When the Muslim army reached Jericho, Sophronius collected all the holy relics including the True Cross, and secretly sent them to the coast, to be taken to Constantinople.[7] The Muslim troops besieged the city some time in November 636. Instead of relentless assaults on the city,[8] they decided to press on with the siege until the Byzantines ran short of supplies and a bloodless surrender could be negotiated.[9]

Although details of the siege were not recorded,[10] it appeared to be bloodless.[1] The Byzantine garrison could not expect any help from the humbled Heraclius. After a siege of four months, Sophronius offered to surrender the city and pay a jizya (tribute), on condition that the caliph came to Jerusalem to sign the pact and accept the surrender.[11] When Sophronius's terms became known to the Muslims, Shurahbil ibn Hasana, one of the Muslim commanders, reportedly suggested that instead of waiting for the caliph to come all the way from Madinah, Khalid ibn Walid should be sent forward as the caliph, as he was very similar in appearance to Umar.[12] The subterfuge did not work. Possibly, Khalid was too famous in Syria, or there may have been Christian Arabs in the city who had visited Madinah and had seen both Umar and Khalid, and knew the difference. Consequently, the Patriarch of Jerusalem refused to negotiate. When Khalid reported the failure of this mission, Abu Ubaidah wrote to caliph Umar about the situation, and invited him to come to Jerusalem to accept the surrender of the city.[1]

Surrender

Year (636, 637, 638?)

The date of the surrender of Jerusalem is debatable. Primary sources, such as Theophilus of Edessa (695–785), offer the year 638, or 636, 636/37, and 637. Academic secondary sources tend to prefer 638.[11][3][7][13][14]

Events

According to some sources, Caliph Umar personally led the hostilities. In early April 637, Umar arrived in Palestine and went first to Jabiya,[6] where he was received by Abu Ubaidah, Khalid, and Yazid, who had traveled with an escort to receive him. Amr was left as commander of the besieging Muslim army.[1]

Upon Umar's arrival in Jerusalem, a pact was composed, known as the Umar's Assurance or the Umariyya Covenant. It surrendered the city and gave guarantees of civil and religious liberty to Christians in exchange for the payment of jizya tax. It was signed by Caliph Umar on behalf of the Muslims, and witnessed by Khalid, Amr, Abd al-Rahman ibn Awf, and Mu'awiya. Depending on the sources, in either 637 or in 638, Jerusalem was officially surrendered to the caliph.[6]

For the Jewish community this marked the end of nearly 500 years of Roman rule and oppression. Umar permitted the Jews to once again reside within the city of Jerusalem itself.[6][15]

It has been recorded in the Muslim chronicles that at the time of the Zuhr prayers, Sophronius invited Umar to pray in the rebuilt Church of the Holy Sepulcher. Umar declined, fearing that accepting the invitation might endanger the church's status as a place of Christian worship, and that Muslims might break the treaty, turning the church into a mosque.[16][17] After staying for ten days in Jerusalem, the caliph returned to Medina.[12]

Legacy

Following the Caliph's instructions, Yazid proceeded to Caesarea, and once again laid siege to the port city. Amr and Shurahbil marched to complete the occupation of Palestine, a task that was completed by the end of the year. Caesarea, however, could not be taken until 640, when at last, the garrison surrendered to Mu'awiya I, then a governor of Syria. With an army of 17,000 men, Abu Ubaidah and Khalid set off from Jerusalem to conquer all of northern Syria. This ended with the conquest of Antioch in late 637.[1] In 639, the Muslims invaded and conquered Egypt.

During his stay in Jerusalem, Umar was led by Sophronius to various holy sites, including the Temple Mount. Seeing the poor state of the place where the Temple once stood, Umar ordered the area cleared of refuse and debris before having a wooden mosque built on the site.[18] The earliest account of such a structure is given by the Gallic bishop Arculf, who visited Jerusalem between 679 and 682, and describes a very primitive house of prayer able to accommodate up to 3,000 worshippers, constructed of wooden beams and boards over preexisting ruins.[19]

More than half a century after the capture of Jerusalem, in 691, the Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik commissioned the construction of the Dome of the Rock over a large outcropping of bedrock on the Temple Mount. The tenth-century historian al-Maqdisi wrote that Abd al-Malik built the shrine in order to compete in grandeur with the city's Christian churches. Whatever the intention, the impressive splendor and scale of the shrine is seen as having helped significantly in solidifying the attachment of Jerusalem to the early Muslim faith.[18]

Over the next 400 years, the city's prominence diminished as Saracen powers in the region jockeyed for control. Jerusalem remained under Muslim rule until it was captured by Crusaders in 1099 during the First Crusade.

Hadith

It is believed in Sunni Islam that Muhammad foretold the conquest of Jerusalem in numerous authentic hadiths in various Islamic sources,[20][21] including a narration mentioned in Sahih al-Bukhari in Kitab Al Jizyah Wa'l Mawaada'ah (The Book of Jizya and Storage):

Narrated `Auf bin Mali: I went to the Prophet during the Expedition to Tabuk while he was sitting in a leather tent. He said, "Count six signs that indicate the approach of the End Times: my death, the conquest of Jerusalem, a plague that will afflict you (and kill you in great numbers) as the plague that afflicts sheep..."[22]

The siege of Jerusalem was carried out by Abu Ubaidah under Umar in the earliest period of Islam along with the Plague of Emmaus (an ancient bubonic plague). The epidemic is famous in Muslim sources because of the death of many prominent companions of Muhammad.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Agha Ibrahim Akram, The Sword of Allah: Khalid bin al-Waleed – His Life and Campaigns (Oxford, U. K.: Oxford University Press, 2004, ISBN 0195977149), 431-434, 438.

- ↑ Geoffrey Greatrex and Samuel N. C. Lieu, The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars (Part II, 363–630 C.E.) (New York, NY and London, U.K.: Routledge (Taylor & Francis), 2002, ISBN 0415146879), 198. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 John F. Haldon, Byzantium in the Seventh Century: The Transformation of a Culture (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1997, ISBN 978-0521319171), 46. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

- ↑ David Nicolle, Yarmuk 636 C.E.: The Muslim Conquest of Syria (Oxford, U.K.: Osprey Publishing Limited, 1994, ISBN 1855324148), 12–14.

- ↑ Bernard Lewis, The Arabs in History (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2002, ISBN 0192803107), 65. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Moshe Gil, A History of Palestine, 634-1099 (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1997, ISBN 978-0521599849), 51-54, 70-71. Retrieved February 15, 2024.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Steven Runciman, A History of the Crusades - Volume 1: The First Crusade and the Foundation of the Kingdom of Jerusalem (Cambridge, U.K: Cambridge University Press, 1987, ISBN 978-0521347709), 2, 17. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

- ↑ The Muslims are said to have lost 4,000 men in the Battle of Yarmouk fought just two months before the siege.

- ↑ Edward Gibbon, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Volume 6 (Philadelphia, PA: J. D. Morris Publishers, 1862), 321.

- ↑ Muslim historians differ in the year of the siege; while Tabari says it was 636, al-Baladhuri placed its date of surrender in 638. al-Baladhuri, The Origins of the Islamic State trans. Philip Khuri Hitti (Beirut, LB: Khayats, 1966), 214. Retrieved February 24, 2024. Agha I. Akram believes 636–637 to be the most likely date.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Meron Benvenisti, City of Stone: The Hidden History of Jerusalem (Berkeley, CA and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 1996, ISBN 0520207688), 14. Retrieved February 1, 2024.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Abu Abdullah al-Waqidi, Futuh al-Sham, Volume 1 (Beirut, LN: Dar Saader, 2010), 162, 169.

- ↑ Abd al-Fattah El-Awaisi, "Umar's Assurance of Safety to the People of Aeia (Jerusalem): A Critical Analytical Study of the Historical Sources," Journal of Islamic Jerusalem Studies 3(2) (Summer 2000): 47–89. "The first Muslim conquest of Jerusalem in Muhrram 17 AH/February 638 CE..." Retrieved February 16, 2024.

- ↑ Theophilus of Edessa, Theophilus of Edessa's Chronicle and the Circulation of Historical Knowledge in Late Antiquity and Early Islam (Liverpool, U.K.: Liverpool University Press, 2011, ISBN 978-1846316975), 114. Retrieved February 16, 2024. (638) "The capture of Jerusalem and the visit of 'Umar." Footnote 254 discusses the different dates from old sources (638, 637, 636/37) and the different scholarly discussions.

- ↑ Michael Zank, "Byzantian Jerusalem," Boston University. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

- ↑ D.J. Sahas, "The Face To Face Encounter Between Patriarch Sophronius Of Jerusalem And The Caliph῾ Umar Ibn Al-Khaṭṭāb: Friends Or Foes?" in The Encounter of Eastern Christianity with Early Islam (Leiden, ND: Brill, 2006, ISBN 978-9047408826), 33–44. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

- ↑ Jalal Naji, "Religious freedom and the building of churches in Arab countries," Acta Universitatis Carolinae Iuridica 64(2) (2018): 145–156. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Leslie J. Hoppe, The Holy City: Jerusalem in the Theology of the Old Testament (Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 2000, ISBN 0814650813), 15. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ↑ Amikam Elad, Medieval Jerusalem and Islamic Worship: Holy Places, Ceremonies, Pilgrimage (Leiden, ND and New York, NY: Brill Publishers, 1999, ISBN 9004100105), 33.

- ↑ Ibn Majah, "Sunan 4042," www.Sunnah.com. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

- ↑ al-Bukhari, "Sahih 3176," www.sunnah.com. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

- ↑ al-Bukhari, "Sahih al-Bukhari Vol. 4, Book 53, Hadith 401," Hadith Collection. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Akram, Agha Ibrahim. The Sword of Allah: Khalid bin al-Waleed – His Life and Campaigns. Oxford, U. K.: Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN 0195977149.

- al-Bukhari. "Sahih 3176," www.sunnah.com. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

- al-Bukhari. "Sahih al-Bukhari Vol. 4, Book 53, Hadith 401," Hadith Collection. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

- al-Baladhuri. The Origins of the Islamic State translated by Philip Khuri Hitti. Beirut, LB: Khayats, 1966. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- al-Waqidi, Abu Abdullah. Futuh al-Sham, Volume 1. Beirut, LN: Dar Saader, 2010.

- Benvenisti, Meron. City of Stone: The Hidden History of Jerusalem. Berkeley, CA and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 1996. ISBN 0520207688

- El-Awaisi, Abd al-Fattah. "Umar's Assurance of Safety to the People of Aeia (Jerusalem): A Critical Analytical Study of the Historical Sources," Journal of Islamic Jerusalem Studies 3(2) (Summer 2000): 47–89. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

- Elad, Amikam. Medieval Jerusalem and Islamic Worship: Holy Places, Ceremonies, Pilgrimage. Leiden, ND and New York, NY: Brill Publishers, 1999. ISBN 9004100105

- Gibbon, Edward. The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Volume 6. Philadelphia, PA: J. D. Morris Publishers, 1862.

- Gil, Moshe. A History of Palestine, 634-1099.. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0521599849

- Greatrex, Geoffrey, and Samuel N. C. Lieu. The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars (Part II, 363–630 C.E.). New York, NY and London, U.K.: Routledge (Taylor & Francis), 2002. ISBN 0415146879

- Haldon, John F. Byzantium in the Seventh Century: The Transformation of a Culture. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1997 (original 1990). ISBN 978-0521319171

- Hoppe, Leslie J. The Holy City: Jerusalem in the Theology of the Old Testament. Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 2000. ISBN 0814650813

- Ibn Majah. "Sunan 4042," www.Sunnah.com. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

- Lewis, Bernard. The Arabs in History. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2002 (original 1993). ISBN 0192803107

- Naji, Jalal. "Religious freedom and the building of churches in Arab countries," Acta Universitatis Carolinae Iuridica 64(2) (2018): 145–156. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

- Nicolle, David. Yarmuk 636 C.E.: The Muslim Conquest of Syria. Oxford, U.K.: Osprey Publishing Limited, 1994. ISBN 1855324148

- Runciman, Steven. A History of the Crusades - Volume 1: The First Crusade and the Foundation of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Cambridge, U.K: Cambridge University Press, 1987 (original 1951). ISBN 978-0521347709

- Sahas, D. J. "The Face To Face Encounter Between Patriarch Sophronius Of Jerusalem And The Caliph῾ Umar Ibn Al-Khaṭṭāb: Friends Or Foes?" in The Encounter of Eastern Christianity with Early Islam. Leiden, ND: Brill, 2006. ISBN 978-9047408826

- Theophilus of Edessa. Theophilus of Edessa's Chronicle and the Circulation of Historical Knowledge in Late Antiquity and Early Islam. Liverpool, U.K.: Liverpool University Press, 2011. ISBN 978-1846316975

- Zank, Michael. "Byzantian Jerusalem," Boston University. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

External links

Link retrieved February 24, 2024.

Coordinates:

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.