| Small intestine | |

|---|---|

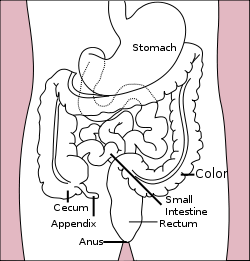

| Diagram showing the small intestine. | |

| Latin | intestinum tenue |

| Gray's | subject #248 1168 |

| Nerve | celiac ganglia, vagus |

| MeSH | Small+intestine |

| Dorlands/Elsevier | i_11/12456563 |

The small intestine is the narrow tube of the gastrointestinal tract (gut) of vertebrates between the stomach and the large intestine that is responsible for most of the digestion. Vertebrate intestines‚ÄĒthe long, tubular portion of the gut that extends from the stomach to the anus or cloaca‚ÄĒ tend to be divided into small intestine and large intestines, with the upper portion designated the small intestine.

Just as the various parts of the body work together harmoniously to provide for the health of the entire body, the small intestine provides an important function for the whole: digestion and absorption of nutrients and water, as well as an immune function in protection against invaders. In turn, the body supports the small intestine's individual purpose of survival, maintenance, and development by providing nourishment for the small intestine's cells and carrying away metabolic waste products.

In cartilaginous fishes and some primitive bony fishes (eg., lungfish, sturgeon), the intestine is relatively straight and short, and many fishes have a spiral valve (Ritchison 2007). Amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals, as well as some fish, tend to have an elongated and coiled small intestine (Ritchison 2007). In mammals, including humans, the small intestine is divided into three sections: the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum. Although it is called "small intestine," it is longer in mammals than is the large intestine, but is narrower in diameter.

Structure in humans

In humans over five years old, the small intestine is about seven meters (23 ft) long; it can be as small as four meters in length (13 feet).

The small intestine is divided into three structural parts:

- duodenum: 26 centimeters (9.84 inches) in length in humans

- jejunum: 2.5 meters (8.2 feet)

- ileum: 3.5 meters (11.5 feet)

The small intestine in humans is typically four to five times longer than the large intestine. On average, the diameter of the small intestine of an adult human measures approximately 2.5 to three centimeters, and the large intestine measures about 7.6 centimeters in diameter.

Food from the stomach is allowed into the duodenum by a muscle called the pylorus, or pyloric sphincter, and is then pushed through the small intestine by a process of muscular-wavelike contractions called peristalsis.

The small intestine is the site where most of the nutrients from ingested food are absorbed and is covered in wrinkles or folds called plicae circulara. These are considered permanent features in the wall of the organ. They are distinct from rugae, which are considered non-permanent or temporary allowing for distention and contraction.

From the plicae circulara project microscopic finger-like pieces of tissue called villi. The small intestine is lined with simple columnar epithelial tissue. The epithelial cells also have finger-like projections known as microvilli that cover the villi. The function of the plicae circulares, the villi, and the microvilli is to increase the amount of surface area available for secretion of enzymes and absorption of nutrients.

While all vertebrates have irregular surfaces to facilitate absorption and secretion, the fine villi in mammals are the most extensive adaptation for increasing the surface area. For example, there are no villi in the small intestine of a frog.

Function

The small intestine is the chief organ of both absorption and digestion. It also protects against foreign invaders.

Absorption

As noted, one purpose of the wrinkles and projections in the small intestine of mammals is to increase surface area for absorption of nutrients, as well as water. The microvilli that cover each villus increase the surface area manyfold. Each villus contains a lacteal and capillaries. The lacteal absorbs the digested fat into the lymphatic system, which will eventually drain into the circulatory system. The capillaries absorb all other digested nutrients.

The surface of the cells on the microvilli are covered with a brush border of proteins, which helps to catch a molecule-thin layer of water within itself. This layer, called the "unstirred water layer," has a number of functions in absorption of nutrients.

Absorption of the majority of nutrients takes place in the jejunum, with the following notable exceptions:

- Iron is absorbed in the duodenum.

- Vitamin B12 and bile salts are absorbed in the terminal ileum.

- Water and lipids are absorbed by passive diffusion throughout.

- Sodium is absorbed by active transport and glucose and amino acid co-transport.

- Fructose is absorbed by facilitated diffusion.

Digestion

The digestion of proteins into peptides and amino acids principally occurs in the stomach but some also occurs in the small intestine. The small intestine is where the most chemical digestion takes place:

- Peptides are degraded into amino acids. Chemical break down begins in the stomach and is further broken down in the small intestine. Proteolytic enzymes, trypsin and chymotrypsin, which are secreted by the pancreas, cleave proteins into smaller peptides. Carboxypeptidase, which is a pancreatic brush border enzyme, splits one amino acid at a time. Aminopeptidase and dipeptidase free the end amino acid products.

- Lipids are degraded into fatty acids and glycerol. Lipid digestion is the sole responsibility of the small intestine. Pancreatic lipase is secreted here. Pancreatic lipase breaks down triglycerides into free fatty acids and monoglycerides. Pancreatic lipase preforms its job with the help of bile salts. Bile salts attach to triglycerides, which aids in making them easier for pancreatic lipase to work.

- Carbohydrates are degraded into simple sugars (e.g., glucose). In the small intestine, pancreatic amylase breaks down carbohydrates into oligosaccharides. Brush border enzymes take over from there. The most important brush border enzymes are dextrinase and glucoamylase, which further break down oligosaccharides. Other brush border enzymes are maltase, sucrase, and lactase.

Histology

The three sections of the mammalian small intestine look similar to each other at a microscopic level, but there are some important differences.

The parts of the intestine are as follows:

| Layer | Duodenum | Jejunum | Ileum |

| serosa | normal | normal | normal |

| muscularis externa | longitudinal and circular layers, with Auerbach's (myenteric) plexus in between | same as duodenum | same as duodenum |

| submucosa | Brunner's glands and Meissner's (submucosal) plexus | no BG | no BG |

| mucosa: muscularis mucosae | normal | normal | normal |

| mucosa: lamina propria | no PP | no PP | Peyer's patches |

| mucosa: epithelium | simple columnar. Contains goblet cells, Paneth cells | Similar to duodenum. Villi very long. | Similar to duodenum. Villi very short. |

Small Intestine Disorders

The following are some disorders of the small intestine:

- Small intestine cancer

- Small intestine obstruction ("high" mechanic ileus)

- Obstruction from external pressure

- Obstruction by masses in the lumen (foreign bodies, bezoar, gallstones)

- Paralytic ileus

- Maropthisis

- Crohn's disease

- Celiac disease

- Carcinoid

- Meckel's Diverticulum

- Gastric dumping syndrome

- Infectious diseases

- Giardiasis

- Scariasis

- Tropical sprue

- Tapeworm infection

- Mesenteric ischemia

- Short bowel syndrome

- Inguinal hernia

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ritchison, G. 2007. BIO 342, Comparative Vertebrate Anatomy: Lecture notes 7‚ÄĒDigestive system Gary Ritchison's Home Page, Eastern Kentucky University. Retrieved November 23, 2007.

- Solomon, E. P., L. R. Berg, and D. W. Martin. 2002. Biology. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole Thomson Learning. ISBN 0030335035.

- Thomson, A., L. Drozdowski, C. Iodache, B. Thomson, S. Vermeire, M. Clandinin, and G. Wild. 2003. Small bowel review: Normal physiology, part 1. Dig Dis Sci 48(8): 1546-1564. PMID 12924651 Retrieved November 23, 2007.

- Thomson, A., L. Drozdowski, C. Iodache, B. Thomson, S. Vermeire, M. Clandinin, and G. Wild. 2003. Small bowel review: Normal physiology, part 2. Dig Dis Sci 48(8): 1565-1581. PMID 12924652 Retrieved November 23, 2007.

- Townsend, C. M., and D. C. Sabiston. 2004. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery: The Biological Basis of Modern Surgical Practice. Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 0721604099.

Additional images

| Digestive system - edit |

|---|

| Mouth | Pharynx | Esophagus | Stomach | Pancreas | Gallbladder | Liver | Small intestine (duodenum, jejunum, ileum) | Colon | Cecum | Rectum | Anus |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.