Spartacus

Spartacus (c. 109 B.C.E. - 71 B.C.E.) the leader of the major slave uprising against the Roman Republic known as the Third Servile War. Probably born in Thrace, he may have been a former soldier who deserted the Roman army, was captured, and sent to the gladiator school at Capua. In 73 B.C.E., some 70 gladiators escaped to Mt. Vesuvius, where they were joined by slaves and farm workers. There, the ragtag group was transformed by Spartacus and his comrades into a first-class fighting force.

At first, the Romans were slow to respond to the uprising, with Spartacus defeating local Roman armies in three sharp engagements. The slaves then conducted raids throughout southern Italy, where their forces grew to 70,000-120,000 men. In 72 B.C.E., the Roman Senate sent two consuls with four legions against the slaves. Spartacus was victorious against these forces in separate battles in central Italy, after which he attempted to lead the slaves north to freedom beyond the Alps. However, they chose instead to turn back to Italy.

In the autumn of 72, the Senate made Marcus Licinius Crassus leader of the war against the slaves. He recruited six additional legions and took up a protective position in south-central Italy. In a final battle with Crassus' main force, Spartacus and 60,000 of his men fell. Crassus crucified 6,600 prisoners from the battle along the Via Appia from Capua to Rome.

Spartacus' body was never found. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, he became a legendary figure of literature, art, and film.

Biography

Origins

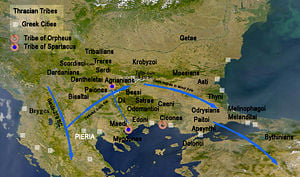

The ancient sources give various accounts on Spartacus' origins. Plutarch describes him as "a Greek of nomadic stock," and said Spartacus' wife, a prophetess, was enslaved with him. Others suggest that his origin as the territory of present Bulgaria. Most, however, claim that Spartacus was born in Thrace. Appian said he was "a Thracian by birth, who had once served as a soldier with the Romans, but had since been a prisoner and sold for a gladiator." Florus characterized him as "a deserter and robber, and afterwards, from consideration of his strength, a gladiator." What seems clear is that he had military experience, was a natural leader, and ended up, for whatever reason, in the position of a gladiator much against his will.

Initial revolt

Spartacus was trained at the gladiatorial school of Lentulus Batiatus near Capua. In 73 B.C.E., he and some 70 followers escaped from the school. Seizing the knives in the cook's shop and a wagon full of weapons, they fled to the area of Mount Vesuvius, near modern-day Naples. His chief aides were gladiators from Gaul and Germania, named Crixus, Castus, Gannicus, and Oenomaus. Spartacus' intention was to leave Italy and return home.

The group of escaped gladiators was joined by rural runaway slaves and succeeded in overrunning the region, plundering and pillaging. The slave-to-citizen ratio at that time was very high, making this rebellion hard for Rome to control. All of Rome's experienced legions were away at the time, and the Senate sent an inexperienced praetor, Claudius Glaber, against the rebels, with a militia of about 3,000. They besieged the rebels on Vesuvius, blocking their escape. Spartacus had ropes made from vines and with his men climbed down a cliff on the other side of the volcano, to the rear of the Roman soldiers, and staged a surprise attack. Not expecting trouble, the Romans had not fortified their camp or posted adequate sentries. As a result, most of the Roman soldiers were caught sleeping and killed, including Claudius Glaber himself.

Spartacus is credited as an excellent military tactician, and his reported experience as a former soldier made him a formidable enemy, but his men were mostly former slave laborers who lacked military training. Hiding out on Mount Vesuvius, which at that time was dormant and heavily wooded, enabled them to train for the upcoming fights with the Romans. Due to the short amount of time expected before battle, Spartacus delegated training to the gladiators, who trained small groups of leaders, and these then trained other small groups and so on, leading to the development of a fully trained army in a matter of weeks. With these successes, more and more slaves flocked to the Spartacan forces, as did many of the herdsmen and shepherds of the region, swelling their ranks greatly, with estimates ranging from 70,000-120,000. The rebel slaves spent the winter of 73–72 B.C.E. arming and equipping their new recruits, and expanding their raiding territory southward to include the towns of Nola, Nuceria, Thurii and Metapontum. By spring, they marched north towards Gaul.

Rome reacts

The Senate, alarmed, now sent two consuls, Gellius Publicola and Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus Clodianus, each with a legion, against the rebels. Among the slaves, Crixus wanted to stay in Italy and plunder, but Spartacus wanted to continue north. Crixus and about 30,000 Gaul and Germanic followers were then defeated by Publicola, and Crixus was killed in battle. Spartacus and his force, however, defeated Lentulus, and then defeated Publicola as well and pushed north. At Mutina (now Modena), he defeated yet another legion under Gaius Cassius Longinus, the governor of Cisalpine Gaul ("Gaul this side of the Alps"). By now, Spartacus's many followers included women, children, and elderly men.

Apparently, Spartacus had intended to march his army out of Italy and into Gaul (now Belgium, Switzerland, and France), or possibly to Hispania to join the rebellion of Quintus Sertorius. However, sources indicate that he changed his mind and turned back south, under pressure from his followers, for they wanted more plunder. A group of about 10,000 or so, however, may have crossed the Alps to return to their homelands. The rest marched back south and defeated two more legions under the new Roman commander, Marcus Licinius Crassus, who at that time was the wealthiest man in Rome.

At the end of 72 B.C.E., Spartacus was encamped in Italy's far south at Rhegium (Reggio Calabria), near the Strait of Messina. There, a deal with Cilician pirates to get them to Sicily fell through. In the beginning of 71 B.C.E., eight legions under Crassus isolated Spartacus' army in Calabria. With the assassination of Quintus Sertorius, the Roman Senate also recalled Pompey from Hispania and Marcus Terentius Varro Lucullus from Macedonia. The stage was now set for a final confrontation, with the full might of Rome arrayed against Spartacus and his army of slaves.

Defeat

Trapped in the south, Spartacus managed to break through Crassus' lines and escape northward toward Brundisium (now Brindisi), but Pompey's forces intercepted them in Lucania. The slaves were routed in a subsequent battle at the river Silarus, where Spartacus is believed to have fallen. According to Plutarch, "After his companions had taken to flight, he stood alone, surrounded by a multitude of foes, and was still defending himself when he was cut down." Appian, however, reports that his fellows fought by his side until the end: "Spartacus was wounded in the thigh with a spear and sank upon his knee, holding his shield in front of him and contending in this way against his assailants until he and the great mass of those with him were surrounded and slain." The body of Spartacus, however, was not found.

After the battle, legionaries rescued 3,000 unharmed Roman prisoners in the rebel camp. Some 6,600 of Spartacus's followers were crucified along the Appian Way from Brundisium to Rome. Crassus never gave orders for the bodies to be taken down, thus travelers were forced to see the bodies for years after the final battle. Around 5,000 slaves, however, escaped the capture. They fled north and were later destroyed by Pompey, who was coming back from Roman Iberia. This enabled him to claim credit for ending this war. Pompey was greeted as a hero in Rome while Crassus received little credit or celebration.

Legacy

When Toussaint L'Ouverture led the slave rebellion of the Haitian Revolution (1791—1804), he was called the "Black Spartacus" by one of his defeated opponents, the Comte de Lavaux. The later revolutionary, Karl Marx, cited Spartacus as his hero, calling him the "finest fellow" antiquity had to offer. The founder of the Bavarian Illuminati, Adam Weishaupt often referred to himself as "Spartacus" within written correspondences.

Spartacus' struggle, often seen as the fight for an oppressed people fighting for their freedom against a slave-owning aristocracy, has found new meaning for modern writers since the nineteenth century. The Italian writer Rafaello Giovagnoli wrote his historical novel, Spartacus, in 1874. It was subsequently translated and published in many European countries.

Spartacus has also been a great inspiration to revolutionaries in more recent times, most notably the Spartacist League of Weimar Germany, as well as the far-left Spartacist groups of the 1970s in Europe and the U.S. Noted Latin American Marxist revolutionary Che Guevara was also an admirer of Spartacus.

The story of Spatarcus and his revolt was also the subject of Stanley Kubrick's 1960 cinematic adaptation of Howard Fast's novel Spartacus. The film starred Kirk Douglas as the rebellious slave Spartacus and Laurence Olivier as his foe, the Roman general and politician Marcus Licinius Crassus. Peter Ustinov won an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his role as slave trader Lentulus Batiatus in the film. The catchphrase "I'm Spartacus!" from this film—from the dramatic scene in which the entire army claims to be Spartacus rather than turn him over to his enemy—has been referenced in a number of other films, television programs, and commercials.

In addition to Howard Fast's historical novel on which Kubrick's film was based, Arthur Koestler wrote a novel about Spartacus called The Gladiators. There is also a novel Spartacus by the Scottish writer Lewis Grassic Gibbon. Spartacus is a prominent character in the novel Fortune's Favorites by Colleen McCullough. There is also a novel The students of Spartacus (Uczniowie Spartakusa) by the Polish writer Halina Rudnicka. Spartacus and His Glorious Gladiators, by Toby Brown, is part of the Dead Famous series of children's history books.

In the performing arts, Spartacus is also the title of a ballet, with a score by composer Aram Khachaturian. The musical Jeff Wayne's Musical Version of Spartacus was released in 1992.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bradley, Keith R. Slavery and Rebellion in the Roman World, 140 B.C.E.–70 B.C.E. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989. ISBN 0253312590.

- Rubinsohn, Wolfgang Zeev. Spartacus' Uprising and Soviet Historical Writing. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 1987. ISBN 0951124315.

- Trow, M.J. Spartacus: The Myth and the Man. Stroud, United Kingdom: Sutton Publishing, 2006. ISBN 0750939079.

- Winkler, Martin M. (ed.). Spartacus: Film and History. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 2007. ISBN 978-1405131802.

External links

All links retrieved February 7, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.