| John Climacus Ἰωάννης τῆς Κλίμακος | |

|---|---|

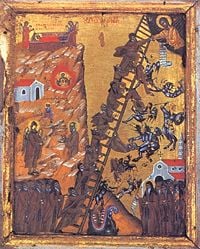

Orthodox icon showing monks ascending to (and falling from) full spiritual attainment, as described in the Ladder of Divine Ascent. | |

| John of the Ladder, John Scholasticus, John Sinaites, John of Sinai | |

| Born | ca. 525 C.E. in Syria |

| Died | March 30, 606 C.E. |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church Eastern Catholic Churches Eastern Orthodox Oriental Orthodox |

| Feast | March 30 |

John Climacus (Ἰωάννης τῆς Κλίμακος) (ca. 525 – March 30, 606 C.E.), also known as John of the Ladder, John Scholasticus and John Sinaites, was a sixth century Christian monk at the monastery on Mount Sinai. He is best known for his pious and prayerful lifestyle, which culminated in the composition of the "Ladder of Divine Ascent" (Scala Paradisi)—a practical manual detailing the stages along the path to spiritual truth. Though originally intended for an ascetic audience, the Scala gradually became a classic account of Christian piety.

John Climacus is revered as a saint by the Roman Catholic, Oriental Orthodox, Eastern Orthodox and Eastern Catholic churches, who celebrate his feast day on March 30th.

Though John was also known as "Scholasticus" (due to the breadth of his learning), he is not to be confused with St. John Scholasticus, Patriarch of Constantinople.

Biography

As with many other Syrian monastic saints, little is known of the life of John Climacus prior to his high profile involvement with the monastery at Mount Sinai. In particular, different accounts provide varied (and mutually exclusive) renditions of his early life, with some claiming that he sought the monastic novitiate as early as sixteen and others that he joined the order after the premature death of his young wife.[1] Regardless of the specific circumstances of his entrance into monastic life, John thrived in this new environment and, after completing his novitiate under Martyrius, he withdrew to a hermitage at the foot of the mountain to practice further austerities.

- In the year 560, and the thirty-fifth of his age, he lost Martyrius by death; having then spent nineteen years in that place in penance and holy contemplation. By the advice of a prudent director, he then embraced an eremitical life in a plain called Thole, near the foot of Mount Sinai. His cell was five miles from the church, probably the same which had been built a little before, by order of the Emperor Justinian, for the use of the monks at the bottom of this mountain, in honour of the Blessed Virgin, as Procopius mentions. Thither he went every Saturday and Sunday to assist, with all the other anchorets and monks of that desert, at the holy office and at the celebration of the divine mysteries, when they all communicated. His diet was very sparing, though, to shun ostentation and the danger of vainglory, he ate of everything that was allowed among the monks of Egypt, who universally abstained from flesh and fish. Prayer was his principal employment; and he practiced what he earnestly recommends to all Christians, that in all their actions, thoughts, and words they should keep themselves with great fervour in the presence of God, and direct all they do to his holy will. By habitual contemplation he acquired an extraordinary purity of heart, and such a facility of lovingly beholding God in all his works that this practice seemed in him a second nature. Thus he accompanied his studies with perpetual prayer. He assiduously read the holy scriptures and fathers, and was one of the most learned doctors of the church.[2]

After forty years of prayer, study and quiet contemplation, when John was about seventy-five years of age, the monks of Sinai persuaded him to accept the leadership of their abbey (ca. 600 C.E.). He acquitted himself in this role with the greatest wisdom, and his reputation spread so far that Pope Gregory the Great wrote to recommend himself to his prayers, and sent him a sum of money for the hospital of Sinai, where the pilgrims were wont to lodge. At this time, he also wrote the Ladder of Divine Ascent, a manual of ascetic practice that has remained a staple of Christian devotionalism throughout the fourteen centuries since its composition (as described below). Four years later, he resigned his charge and returned to his hermitage to prepare for death:

- St. John sighed continually under the weight of his dignity during the four years that he governed the monks of Mount Sinai; and as he had taken upon him that burden with fear and reluctance, he with joy found means to resign the same a little before his death. Heavenly contemplation, and the continual exercise of divine love and praise, were his delight and comfort in his earthly pilgrimage: and in this imitation of the functions of the blessed spirits in heaven he placeth the essence of the monastic state. In his excellent maxims concerning the gift of holy tears, the fruit of charity, we seem to behold a lively portraiture of his most pure soul. He died in his hermitage on the 30th day of March, in 605, being fourscore years old.[3]

The Ladder of Divine Ascent

- See also: Hesychasm

The Scala Paradisi ("Ladder of Divine Ascent" or Klimax (from which the name "John Climacus" was derived)), John's textbook of practical spirituality, is addressed to anchorites and cenobites, and treats of the means by which the highest degree of religious perfection may be attained. Divided into thirty parts ("steps") in memory of the thirty years of the hidden life of Christ, it presents a picture of the virtuous life of an idealized ascetic, brought into sharp focus through the use of a great many parables and historical touches. Unlike many spiritual texts, whose meaning is often obfuscated through mystical language, the Scala is notable for its practical, incremental approach to theosis (the divinization of the mortal flesh). To this end, it is one of the first Christian texts to recommend the practice of Hesychasm—the quelling of internal conflicts and stimuli in the service of spiritual ends. As suggested in the Scala, "Hesychasm is the enclosing of the bodiless mind (nous) in the bodily house of the body."[4]

Further, the book discusses monastic virtues and vices and holds dispassionateness (apatheia) as the ultimate contemplative and mystical good for an observant Christian. This attitude is pithily presented in the second "step" of the ladder, "On Detachment":

- If you truly love God and long to reach the kingdom that is to come, if you are truly pained by your failings and are mindful of punishment and of the eternal judgment, if you are truly afraid to die, then it will not be possible to have an attachment, or anxiety, or concern for money, for possessions, for family relationships, for worldly glory, for love and brotherhood, indeed for anything of earth. All worry about one's condition, even for one's body, will be pushed aside as hateful. Stripped of all thought of these, caring nothing about them, one will turn freely to Christ. One will look to heaven and to the help coming from there, as in the scriptural sayings: "I will cling close to you" (Ps. 62:9) and "I have not grown tired of following you nor have I longed for the day or the rest that man gives" (Jer. 17:16).

- It would be a very great disgrace to leave everything after we have been called—and called by God, not man—and then to be worried about something that can do us no good in the hour of our need, that is, of our death. This is what the Lord meant when He told us not to turn back and not to be found useless for the kingdom of heaven. He knew how weak we could be at the start of our religious life, how easily we can turn back to the world when we associate with worldly people or happen to meet them. That is why it happened that when someone said to Him, "Let me go away to bury my father," He answered, "Let the dead bury the dead" (Matt. 8:22).[5]

The teachings of the Scala were sufficiently prominent to justify their visual representation in iconic form (as seen above). These icons generally depict several people climbing a ladder; at the top is Jesus, prepared to receive the climbers into Heaven. Also shown are angels helping the climbers, and demons attempting to shoot with arrows or drag down the climbers, no matter how high up the ladder they may be. As with all Orthodox icons, one of the primary functions of these images was to engender the teachings of the text in such a way that it was understandable even to those who were unable to experience it directly (due to the prevalence of illiteracy and the paucity of physical texts).

Contents

The Scala consists of 30 chapters or "rungs,"

- 1–4: renouncement of the world and obedience to a spiritual father

- 1. Περί αποταγής (On renunciation of the world)

- 2. Περί απροσπαθείας (On detachment)

- 3. Περί ξενιτείας (On exile or pilgrimage; concerning dreams that beginners have)

- 4. Περί υπακοής (On blessed and ever-memorable obedience (in addition to episodes involving many individuals))

- 5–7: penitence and affliction (πένθος) as paths to true joy

- 5. Περί μετανοίας (On painstaking and true repentance which constitutes the life of the holy convicts; and about the Prison)

- 6. Περί μνήμης θανάτου (On remembrance of death)

- 7. Περί του χαροποιού πένθους (On joy-making mourning)

- 8–17: defeat of vices and acquisition of virtue

- 8. Περί αοργησίας (On freedom from anger and on meekness)

- 9. Περί μνησικακίας (On remembrance of wrongs)

- 10. Περί καταλαλιάς (On slander or calumny)

- 11. Περί πολυλογίας και σιωπής (On talkativeness and silence)

- 12. Περί ψεύδους (On lying)

- 13. Περί ακηδίας (On despondency)

- 14. Περί γαστριμαργίας (On that clamorous mistress, the stomach)

- 15. Περί αγνείας (On incorruptible purity and chastity, to which the corruptible attain by toil and sweat)

- 16. Περί φιλαργυρίας (On love of money, or avarice)

- 17. Περί αναισθησίας (On non-possessiveness (that hastens one Heavenwards))

- 18–26: avoidance of the traps of asceticism (laziness, pride, mental stagnation)

- 18. Περί ύπνου και προσευχής (On insensibility, that is, deadening of the soul and the death of the mind before the death of the body)

- 19. Περί αγρυπνίας (On sleep, prayer, and psalmody with the brotherhood)

- 20. Περί δειλίας (On bodily vigil and how to use it to attain spiritual vigil, and how to practise it)

- 21. Περί κενοδοξίας (On unmanly and puerile cowardice)

- 22. Περί υπερηφανείας (On the many forms of vainglory)

- 23. Περί λογισμών βλασφημίας (On mad pride and (in the same Step) on unclean blasphemous thoughts; concerning unmentionable blasphemous thoughts)

- 24. Περί πραότητος και απλότητος (On meekness, simplicity, and guilelessness which come not from nature but from conscious effort, and about guile)

- 25. Περί ταπεινοφροσύνης (On the destroyer of the passions, most sublime humility, which is rooted in spiritual perception)

- 26. Περί διακρίσεως (On discernment of thoughts, passions and virtues; on expert discernment; brief summary of all aforementioned)

- 27–29: acquisition of hesychia or peace of the soul, of prayer, and of apatheia (absence of afflictions or suffering)

- 27. Περί ησυχίας (On holy stillness of body and soul; different aspects of stillness and how to distinguish them)

- 28. Περί προσευχής (On holy and blessed prayer, the mother of virtues, and on the attitude of mind and body in prayer)

- 29. Περί απαθείας (Concerning Heaven on earth, or Godlike dispassion and perfection, and the resurrection of the soul before the general resurrection)

- 30. Περί αγάπης, ελπίδος και πίστεως (Concerning the linking together of the supreme trinity among the virtues; a brief exhortation summarizing all that has said at length in this book)

On this ordering, Duffy has commented:

- The ladder image, more visually compelling for a start, was in any case used for a substantially different purpose. Though not the only structural principle in operation in the work, this device, with its thirty steps, supplies a definite, if somewhat lightly attached, framework. It is true that the text of Climacus, as laid out, does not show anything like a strict hierarchical progression from one spiritual step to the next; however, it is not quite fair to conclude, as is sometimes done, that the presentation of vices and virtues is unsystematic. In fact, as Guerric Couilleau has demonstrated, there is a surprisingly high degree of pattern to be detected in groups of steps and some subtle thematic correspondences between groups and individual topics within them. One might call this logical or even theological order, because it is based on doctrinal content.[6]

Veneration

His feast day is March 30 in East and West. The Orthodox Church also commemorates him on the fourth Sunday of the Great Lent. Many churches are dedicated to him in Russia, including a church and belltower in the Moscow Kremlin.

Notes

- ↑ For an account of this discrepancy, compare Farmer ("He was married in early life and became a monk on the death of his wife" (267)) and Butler ("At sixteen years of age he renounced all the advantages which the world promised him to dedicate himself to God in a religious state, in 547" (703)). Given the highly truncated life expectancies that characterized this period, it is even theoretically possible that both accounts are historically accurate.

- ↑ Butler, 703. This passage seems to echo many standard hagiographical tropes, though its claim concerning John's advanced scholarship is echoed by the clear and penetrating quality of the Ladder of Divine Ascent (described below).

- ↑ Butler, 704.

- ↑ Climacus XXVII.

- ↑ John Climacus, II, 81.

- ↑ Duffy, 6.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

This article incorporates text from the public-domain Catholic Encyclopedia of 1913.

- Butler, Alban. Lives of the Saints. Edited, revised, and supplemented by Herbert Thurston and Donald Attwater. Palm Publishers, 1956.

- Climacus, John. The Ladder of Divine Ascent (Scala paradisi). Translation by Colm Luibheid and Norman Russell. New York; Toronto: Paulist Press, 1982. ISBN 0809123304

- Duffy, John. “Embellishing the Steps: Elements of Presentation and Style” in "’The Heavenly Ladder’ of John Climacus." Dumbarton Oaks Papers 53, 1999, 1-17.

- Farmer, David Hugh. The Oxford Dictionary of Saints. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 1997. ISBN 0192800582

- Mack, Fr. John. Ascending the Heights - A Layman's Guide to The Ladder of Divine Ascent. Ben Lomond, CA: Conciliar Press, 1999. ISBN 1888212179

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.