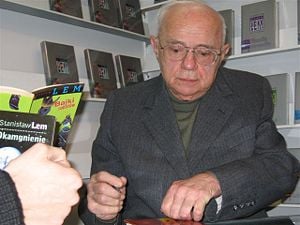

Stanisław Lem (September 12, 1921 – March 27, 2006) was a Polish science fiction, philosophical and satirical writer. His books have been translated into 41 languages and have sold over 27 million copies[1] At one point, he was the most widely read non-English-language science fiction author in the world.[2]

His works often veer into philosophical speculation on technology, the nature of intelligence, the impossibility of mutual communication and understanding, despair about human limitations and humankind's place in the universe. They are sometimes presented as fiction, to avoid both the trappings of academic life and the limitations of readership and scientific style, but others are in the form of essays or philosophical books. Translations of his works are difficult; Michael Kandel's translations into English have generally been praised as capturing the spirit of the original.

Biography

Lem was born in 1921 in Lwów, Poland (now Ukraine). He was the son of Sabina Woller and Samuel Lem, a physician in the Austro-Hungarian army. Lem grew up in wealthy surroundings. Of Jewish ancestry,[3] [4] he was raised a Roman Catholic and later viewed himself as an atheist "for moral reasons" [5] He studied medicine at Lwów University (1939-1941). During World War II and Nazi occupation, Lem was able to survive with false papers working as a car mechanic and welder, and was a member of the resistance fighting against the Germans. He resumed his studies in 1944. In 1946, Lwów had been annexed by the Soviet Ukraine[6] and Lem, as many other Poles, was repatriated from the Kresy to Kraków where he took up medical studies at the Jagiellonian University. After finishing his studies, Lem failed his last exam on purpose because he refused to give answers according to the ideology of Lyssenkoism. This also prevented him from becoming a military doctor. Instead, he had to work as a research assistant in a scientific institution where he started to write stories in his spare time.

He made his literary debut in 1946 as a poet, and at that time he also published several dime novels. Beginning that year, Lem's first novel Człowiek z Marsa (The Man from Mars) was serialized in the Polish magazine Nowy Świat Przygód (New World of Adventures). Between 1947 and 1950 Lem, while continuing his work as a scientific research assistant, published poems, short stories, and scientific essays. However, at that time&mash;the era of Stalinism—it was difficult to publish anything that was not directly suggested and approved by the communist party. For example, the novel Szpital Przemienienia (Hospital of the Transfiguration) was finished by Lem in 1948, but it was suppressed by censors of the People's Republic of Poland until 1955. In 1951, he published his first science fiction novel, Astronauci (Astronauts); this work, showing many traces of socialist realism, was commissioned by the communist authorities. Lem was forced to include many references to the 'glorious future of communism' in the text. He would later criticize this novel (as several others of his early pieces) as simplistic; nonetheless the publication of this book convinced him to become a full-time writer[6].

The death of Joseph Stalin was followed by a period of reform known as destalinization. In Poland it touched off the Polish October of 1956 (when Władysław Gomułka replaced Bolesław Bierut as the head of PZPR), producing greater freedom of speech and thought in Poland. Lem then started his career as a serious international science fiction author, writing some 17 books in the next dozen years; translations of his work began to appear abroad (although mostly in the Eastern Bloc countries). In 1957 he published his first non-fiction, philosophical book, Dialogi. Dialogi (Dialogs) and Summa Technologiae from 1964 are his two most famous philosophical texts. The Summa is notable as a unique analysis of prospective social, cybernetic, and biological advances. In this work, Lem discusses philosophical implications of technologies that were completely in the realm of science fiction at the time, but are gaining importance today–such as virtual reality and nanotechnology. Over subsequent decades, he published many books, both science-fiction and philosophical/futurological, although near the end of his life he tended to concentrate on philosophical texts and essays.

He gained international fame for The Cyberiad, a series of short stories from a mechanical universe ruled by robots, first published in English in 1974. His best known novels include Solaris in 1961, Głos pana (His Master's Voice) in 1983, and Fiasko (Fiasco) in 1987. A major theme of these last three novels is the futility of mankind's attempts to comprehend the truly alien. Solaris was made into a film in 1972 by Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky, winning a Special Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival in 1972; later in 2002, a Hollywood remake was shot by Steven Soderbergh, starring George Clooney.[6]

In 1982, with martial law being declared in the People's Republic of Poland, Lem left his home country and moved to Berlin where he became a fellow of the Wissenschaftskolleg (Institute for Advanced Study). After that, he settled in Vienna. He returned to Poland in 1988.

Lem died in Kraków on March 27, 2006 at the age of 84 after a battle with heart disease.

Honors

- 1957 - City of Kraków's Prize in Literature (Nagroda Literacka miasta Krakowa)

- 1965 - Minister's of Culture and Art 2nd Level Prize (Nagroda Ministra Kultury i Sztuki II stopnia)

- 1973 - Minister's of Foreign Affairs Prize for popularization of Polish culture abroad (nagroda Ministra Spraw Zagranicznych za popularyzację polskiej kultury za granicą)

- 1972 - member of commission "Polska 2000" of Polish Academy of Sciences

- 1973 - Minister's of Culture and Art Prize (nagroda literacka Ministra Kultury i Sztuki) and honorary member of the Science Fiction Writers of America

- 1976 - State's Award 1st Level in the area of literature (Nagroda Państwowa I stopnia w dziedzinie literatury)

- 1981 - Doctor honoris causa honorary degree from the Wrocław Polytechnic

- 1985 - State's Award from Austria for the contribution to European culture (austriacka nagroda państwowa w dziedzinie kultury europejskiej)

- 1991 - Franz Kafka's State's Award from Austria in the area of literature (austriacka nagroda państwowa im. Franza Kafki w dziedzinie literatury)

- 1994 - member of the Polish Academy of Learning

- 1996 - received Order of the White Eagle

- 1997 - honorary citizen of Kraków

- 1998 - Doctor honoris causa: University of Opole, Lwów University, Jagiellonian University

- 2003 - Doctor honoris causa of University of Bielefeld

SFWA controversy

Lem was awarded an honorary membership in the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America (SFWA) in 1973 despite being technically ineligible (honorary membership could only be given to authors who had not been published in the U.S. The fact that he had a U.S. publication at that point was overlooked.) Lem, however, never had a high opinion of American science-fiction, describing it as ill thought-out, poorly written, and interested more in making money than ideas or new literary forms.[7] Lem's honorary membership was rescinded in 1976 after some of his comments strongly criticizing SFWA were published. He was invited to stay on with the organization with a regular membership. (Lem singled out only one American SF writer for praise, Philip K. Dick - see the 1986 English-language anthology of his critical essays, Microworlds. Dick, however, considered Lem to be a composite committee operating on the order of the Party to gain control over the public opinion.[8] After many members (including Ursula K. Le Guin) protested Lem's treatment by the SFWA, a member offered to pay his dues. Lem never responded to the offer. He had also been critical of science fiction in general, and had recently distanced himself from the genre, saying that his early works may have been SF, but his later ones were more mainstream.[9][7]

Themes

Several specific themes recur in all his works, however Lem's fiction is often divided into two major groups[6]. The first includes his more traditional science fiction, with its speculations of technological advances, space travel, and alien worlds, such as Eden (1959), Powrót z gwiazd (1961; Return from the Stars), Solaris (1961), Niezwyciężony (1964; The Invincible), Głos pana (1968; His Master's Voice), and Opowieści o pilocie Pirxie (1968; Tales of Pirx the Pilot). The second group contains dark allegorical tales, or fables, such as Dzienniki gwiazdowe (1957; The Star Diaries), Pamiętnik znaleziony w wannie (1961; Memoirs Found in a Bathtub), and Cyberiada (1965; The Cyberiad).

One of Lem's primary themes was the impossibility of communication between humans and profoundly alien civilizations. His alien societies are often incomprehensible to the human mind including swarms of mechanical flies (in The Invincible) and a large Plasma Ocean (in Solaris). Many of his books like Fiasko or Eden describe the failure of first contact. Lem's book Return from the Stars follows an astronaut's adjustment to a radically changed human society after spending 100 years in space. In his book Głos Pana (His Master's Voice) Lem is critical of humanity's intelligence and intentions in deciphering and truly comprehending an apparent message from space.

He wrote about human technological progress and the problem of human existence in a world where technological development makes biological human impulses obsolete or dangerous (a theme famously explored by Aldous Huxley in his celebrated work, Brave New World). He was also critical of most of science fiction, criticizing sci-fi novels in his novels (Głos Pana), literary and philosophical essays (Fantastyka i futurologia) and interviews.[10] In the 1990s Lem forswore science fiction writing, returning to futurological prognostications, most notably those expressed in Okamgnienie (Blink of an Eye). He became increasingly critical of modern technology in his later life, criticizing inventions such as the Internet.[10]

In many novels, humans become an irrational and emotional liability to their machine partners, who are not perfect either. Issues of technological utopias appeared in Peace on Earth, Observation on the Spot, and, to a lesser extent, The Cyberiad.

Lem often placed his characters—like the spaceman Ijon Tichy of The Star Diaries, Pirx the pilot (of Tales of Pirx the Pilot), or the astronaut Hal Bregg of Return from the Stars in strange, new settings. Thrust into the unknown, he used them to personify various aspects of the possible futures, often having them balance on the thin line separating his belief in the inherent goodness of humanity and his deep pessimism about human limitations.

He also sometimes deploys a wicked sense of humor in his descriptions of even the darkest human situations—most famously in The Futurological Congress and Memoirs Found in a Bathtub. In this regard, he has sometimes been compared to Kurt Vonnegut or Franz Kafka. Many of his lighter tales are about Ijon Tichy, a cosmic traveller in his one-man spaceship, whose adventures challenge commonly accepted ideas about things like time travel, the nature of the soul, and the origin of the universe, in a satiric and ironic, yet undeniably logical way. For example, in The Futurological Congress, Lem portrays a hilarious satire on government and academic conferences. In a Kafkaesque turn, at a hotel in Costa Rica, a conference to propose solutions to overpopulation in a time of violence and terrorism soon dissolves into anarchy as the hotel's water supply is contaminated by a hallucinogen.

His three most famous novels are deeply philosophical, and comment about the nature of the human soul.[6] Solaris, twice adapted into a movie, is set on an isolated space station, is a deeply philosophical work about contact with a completely alien lifeform–a planet-wide sentient ocean. Głos Pana (His Master's Voice) is another classic of traditional science fiction themes. Also very philosophical - much more so then Solaris - it tells the story of the scientists effort to decode, translate and understand an Extraterrestrial transmission, critically approaching humanity's intelligence and intentions in deciphering and truly comprehending a message from outer space. Lem's third great book is The Cyberiad. Subtitled Fables for the Cybernetic Age, it is a collection of comic tales about two intelligent robots who travel about the galaxy solving engineering problems; but a deeper reading reveals a wealth of profound insights into the human condition.

Influence

With translation into 36 languages and circulation of over twenty million copies, Lem is the most successful Polish author. Nonetheless his commercial success has been limited, as the bulk of his publication was made during the communist era in Poland in the COMECON countries (especially People's Republic of Poland, Soviet Union, and East Germany). Due to the communist economy his earnings were small despite the numbers of books sold. Only in West Germany did Lem enjoy both a critical and commercial success, though in the recent years the interest in his books has waned.

The majority of Lem's works have been translated into English, making him unique amongst non-English science fiction writers. Much of his success in the English world can be credited to excellent translations by Michael Kandel.[11]

Stanisław Lem, whose works were influenced by such masters of Polish literature as Cyprian Norwid and Stanislaw Witkiewicz, chose the language of science fiction because in the communist People's Republic of Poland it was easier — and safer — to express ideas veiled in the world of fantasy and fiction than in the world of reality. Despite this — or perhaps because of it — he has become one of the most highly acclaimed science-fiction writers, hailed by critics as equal to the likes of H.G. Wells or Olaf Stapledon.[12]

Lem's works influenced not only the realm of literature, but that of science as well. In 1981 the philosophers Douglas R. Hofstadter and Daniel C. Dennett included three extracts from Lem’s fiction in their important annotated anthology The Mind's I. Hofstadter commented that Lem’s "literary and intuitive approach… does a better job of convincing readers of his views than any hard-nosed scientific article… might do".[12].

Lem's works have even been used as text books for philosophy students[13]

Texts by Lem were set to music by Esa-Pekka Salonen in his 1982 piece, Floof.

Works

Fiction

- Człowiek z Marsa (1946, only in a magazine in sequels) - The Man from Mars. Lem's earliest novel of which he often said that 'it should be forgotten'; however he didn't prevent later republications

- Szpital przemienienia (1948) - Novella, published in book form in 1955 as Czas nieutracony: Szpital przemienienia. Non-SF book about a doctor working in a Polish asylum. Translated into English by William Brand as Hospital of the Transfiguration (1988). Released as a film in 1979.

- Astronauci (Astronauts, 1951) - juvenile science fiction novel. In early 21st century, it is discovered that Tunguska meteorite was a crash of a reconnaissance ship from Venus, bound to invade the Earth. A spaceship sent to investigate finds that Venusians killed themselves in atomic war first. Released as a film in 1960.

- Obłok Magellana (The Magellanic Cloud, 1955, untranslated into English)

- Sezam (1955) - Linked collection of short fiction, dealing with time machines used to clean up Earth's history in order to be accepted into intergalactic society. Not translated into English.

- Dzienniki gwiazdowe (1957, expanded until 1971) - Collection of short fiction dealing with the voyages of Ijon Tichy. Translated into English and expanded as The Star Diaries (1976, translated by Michael Kandel), later published in 2 volumes as Memoirs of a Space Traveller (1982, second volume translated by Joel Stern).

- Inwazja z Aldebarana (1959) - Collection of science fiction stories. Translated into English as The Invasion from Aldebaran.

- The Investigation (Śledztwo, 1959; trans. 1974) - philosophical mystery novel. Released as a film in 1979.

- Eden (1959) - Science fiction novel; after crashing their spaceship on the planet Eden, the crew discovers it is populated with an unusual society. Translated into English by Marc E. Heine as Eden (1989).

- Ksiega robotów (1961) - Released in the US as Mortal Engines (also contains The Hunt from Tales of Pirx the Pilot).

- Return from the Stars (Powrót z gwiazd, 1961; trans. 1980) - SF novel. An astronaut returns to Earth after a 127 year mission.

- Solaris (1961) - SF novel. The crew of a space station is strangely influenced by the living ocean as they attempt communication with it. Translated into English from the French translation by Joanna Kilmartin and Steve Cox (author) as Solaris (1970). Made into a Russian film in 1972, and as a US film in 2002.

- Memoirs Found in a Bathtub (Pamiętnik znaleziony w wannie, 1961; trans. 1973) - Novel set in the distant future about a secret agent, whose mission is so secret that no one can tell him what it is.

- The Invincible (Niezwyciężony, 1964; translated by Wendayne Ackerman from the German translation 1973) - SF novel. The crew of a space cruiser searches for a disappeared ship on the planet Regis III, discovering swarms of insect-like micromachines.

- The Cyberiad (Cyberiada, 1967; transl. by Michael Kandel 1974) - collection of humorous stories about the exploits of Trurl and Klapaucius, "constructors" among robots. The stories of Douglas Adams have been compared to the Cyberiad. [5]

- Głos pana (1968) - SF novel about the effort to translate an extraterrestrial radio transmission. Translated into English by Michael Kandel as His Master's Voice.

- Ze wspomnień Ijona Tichego; The Futurological Congress (Kongres futurologiczny, 1971) - An Ijon Tichy short story, published in the collection Bezsenność.

- Ze wspomnień Ijona Tichego; Professor A. Dońda (1971)

- Doskonała próżnia (1971) - Collection of book reviews of nonexistent books. Translated into English by Michael Kandel as A Perfect Vacuum.

- Opowieści o pilocie Pirxie (1973) - Collection of linked short fiction involving the career of Pirx. Translated into English in two volumes (Tales of Pirx the Pilot and More Tales of Pirx the Pilot)

- Wielkość urojona (1973) - Collection of introductions to nonexistent books, as written by artificial intelligences. Translated into English as Imaginary Magnitude. Also includes Golem XIV, a lengthy essay/short story on the nature of intelligence delivered by eponymous US military computer. In the personality of Golem XIV, Lem with a great amount of humor describes an ideal of his own mind.

- Katar (1975) - SF novel. A former US astronaut is sent to Italy to investigate a series of mysterious deaths. Translated into English as The Chain of Chance.

- Golem XIV (1981) - Expansion of an essey/short story found in Wielkość urojona.

- Wizja lokalna (1982) - Ijon Tichy novel about the planet Entia. Not translated into English.

- Fiasco (Fiasko, 1986, trans. 1987) - SF novel concerning an expedition to communicate with an alien civilization that devolves into a major fiasco.

- Biblioteka XXI wieku (1986) - Library of 21st Century includes Perfect Vacuum, Imaginary Magnitude and others

- Peace on Earth (Pokój na Ziemi, 1987; transl. 1994) - Ijon Tichy novel. A callotomized Tichy returns to Earth, trying to reconstruct the events of his recent visit to the Moon.

- Zagadka (The Riddle, 1996) - Short stories collection. Not translated into English.

- Fantastyczny Lem (The fantastical Lem, 2001). Short stories collection. Not translated into English.

Nonfiction

- Dialogi (1957) - Non-fiction work of philosophy. Translated into English by Frank Prengel as Dialogs.

- Wejście na orbitę (1962) - Not translated into English. Title translates as Going into Orbit.

- Summa Technologiae (1964) - Philosophical essay. Partially translated into English.

- Filozofia Przypadku (1968) - Nonfiction. Not translated into English. Title translates to Philosophy of Coincidence or The Philosophy of Chance.

- Fantastyka i futurologia (1970) - Critiques on science fiction. Some parts were translated into English in the magazine SF Studies in 1973-1975, selected material was translated in the single volume Microworlds (New York, 1986).

- Rozprawy i szkice (1974) - Nonfiction collection of essays on science, science fiction, and literature in general. Not translated into English. Title translates to Essays and drafts.

- Wysoki zamek (1975) - Autobiography of Lem's childhood before World War II. Translated into English as Highcastle: A Remembrance.

- Rozprawy i szkice (1975) - Essays and sketches. Not translated into English.

- Lube Czasy (1995) - Not translated into English. Title translates to Pleasant Times.

- Dziury w całym (1995) - Not translated into English. Title translates to Looking for Problems.

- Tajemnica chińskiego pokoju (1996) - Collection of essays on the impact of technology on everyday life. Not translated into English. Title translates to Mystery of the Chinese Room.

- Sex Wars (1996) - Not translated into English.

- Bomba megabitowa (1999) - Collection of essays about the potential downside of technology, including terrorism and artificial intelligence. Not translated into English. Title translates to The Megabit Bomb.

- Świat na krawędzi (2000) - The World at the Edge. Interviews with Lem.

- Okamgnienie (2000) - Collection of essays on technological progress since the publication of Summa Technologiae. Not translated into English. Title translates to A Blink of an Eye.

- Tako rzecze Lem (And Lem says so, 2002) - Interviews with Lem. Not translated into English.

- Mój pogląd na literaturę (My View of Literature, 2003) - Not translated into English.

- Krótkie zwarcia (Short Circuits, 2004) - Essays. Not translated into English.

- Lata czterdzieste. Dyktanda. (The 40s, 2005) - Lem's works from the 1940s. Not translated into English.

Film and TV adaptations

Lem was well-known for criticizing the films based on his work, including the famous interpretation of Solaris by Andrei Tarkovsky (1972), which he claimed to be "Crime and Punishment in space."

- Der Schweigende Stern (First Spaceship on Venus, 1959)

- Przekładaniec (Layer Cake/Roly Poly, 1968, by Andrzej Wajda )

- Ikarie XB1 (aka White Planet or Voyage to the End of the Universe, Czechoslovakia 1963) [6] - based on Oblok Magellana, uncredited

- Solaris (1972, by Andrei Tarkovsky)

- Un si joli village (1973, by Étienne Périer)

- Test pilota Pirxa or Дознание пилота Пиркса (The Investigation, joint Soviet-Hungary-Polish production, 1978, directed by Marek Piestrak)

- Szpital przemienienia (Hospital of the Transfiguration, 1979, by Edward Zebrowski)

- Victim of the Brain (1988, by Piet Hoenderdos)

- Marianengraben (1994, directed by Achim Bornhak, written by Lem and Mathias Dinter)

- Solaris (2002, by Steven Soderbergh)

Notes

- ↑ Stanislaw Lem 1921 - 2006. Obituary at Lem's official site. Last accessed on 30 June 2006.

- ↑ Arkady and Boris Strugatsky. Roadside Picnic (Introduction) Link (New York: MacMillan Publishing Co., Inc, 1972. Last accessed on 30 June 2006.

- ↑ [1] Stanislaw Lem, "Chance and Order," Translated, from the German, by Franz Rottensteiner. The New Yorker 59 (30 January 1984): 88-98 an autobiographical essay

- ↑ Obituary, [[Jewish Chronicle, 18 May 2006

- ↑ [2] "An Interview with Stanislaw Lem "by Peter Engel. The Missouri Review 7 (2) (1984) .

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 "Lem, Stanislaw." (2006) In Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 [3]. Lem Stanislaw website.Retrieved May 22, 2008.

- ↑ P.K.Dick, Letter to FBI on Lem's homepage. Retrieved May 22, 2008.

- ↑ sfwa.org.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 http://www.lem.pl/cyberiadinfo/english/interview2/interview.htm

- ↑ Franz Rottensteiner, View from Another Shore: European Science Fiction. (Liverpool University Press, 1999, ISBN 0853239428), 252 Google Print, 252.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 [4] "Stanislaw Lem: Author who used science to express philosophical truth" Obituary. The Times, 2006-03-28. Retrieved May 22, 2008.

- ↑ For instance, in the subject "Natural and Artificial Thinking," Faculty of Math. & Phys., Charles Univ. Prague, or at Masaryk Univ. in Brunn - philosophy in sci-fi Link. Last accessed on 30 June 2006.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Acta Lemiana Monashiensis pod red. Lecha Kellera „Acta Polonica Monashiensis” 2002, vol. 2, nr 2 Monash University 2003, 207 s. review in Polish

- Jarzębski, Jerzy. Zufall und Ordnung: Zum Werk Stanislaw Lems, trans. Friedrick Griese [from Przypadek i Ład. O twórczości Stanisława Lema] Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1986 review.Retrieved May 22, 2008.

- Swirski, Peter. Stanislaw Lem Reader. Northwestern University Press, 1997, ISBN 081011495X description. Retrieved May 22, 2008.

- Ziegfeld, Richard E., Stanislaw Lem. New York: Frederick Ungar, 1985. ISBN 0804429944 review

External links

All links retrieved February 9, 2023.

- Official site maintained by Lem's son and secretary

- "Wired" magazine on Lem and Solaris

- Science Fiction as a Model for Probabilistic Worlds: Stanislaw Lem's Fantastic Empiricism, Dagmar Barnouw, Science Fiction Studies, # 18 = Volume 6, Part 2 = July 1979

- Stanislaw Lem Bibliography

- To Solaris and beyond, Philosopher's Zone Australian Broadcasting Corporation discussion about Lem's works mp3 format.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.