Teotihuacan

| Pre-Hispanic City of Teotihuacán* | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| State Party | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iii, iv, vi |

| Reference | 414 |

| Region** | Latin America and the Caribbean |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1987 (11th Session) |

| * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. ** Region as classified by UNESCO. | |

Teotihuacán was the largest pre-Columbian city in the Americas in the first half of the first millennium C.E.. It was also one of the largest cities of the world with a population estimated at 125,000–250,000. Teotihuacán became the center of a major civilization or culture which also bears its name, and which at its greatest extent included much of central Mexico. Its influence spread throughout Mesoamerica.

The city reached its apex between 150 and 450 C.E.. Districts in the city housed people from across the Teotihuacáno empire. Teotihuacáno monumental architecture was characterized by stepped pyramids that were later adopted by the Mayans and Aztecs. The city is also notable for its lack of fortifications.

What is known of this influential, industrious city comes from Mayan inscriptions recounting the tales of Teotihuacán nobility, who were widely traveled. Teotihuacános practiced human sacrifice, with the victims probably being enemy warriors captured in battle and then brought to the city to be ritually sacrificed in ceremonies to insure that the city could prosper. Sometime during the seventh or eighth centuries C.E. the city was sacked and burned, either as the result of an invasion or from an internal uprising.

Teotihuacán was located in what is now the San Juan Teotihuacán municipality, about 24.8 miles northeast of Mexico City. It covers a total surface area of eight square miles and was made a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987.

Name

The name Teotihuacán was given by the Nahuatl-speaking Aztec people centuries after the fall of the city. The term has been glossed as "birthplace of the gods," reflecting Aztec creation myths about the city. Another translation interprets the name as "place of those who have the road of the gods."

The Maya name of the city is unknown, but it appears in hieroglyphic texts from the Maya region as puh, or Place of Reeds, a name similar to several other Central Mexican settlements.

Site layout

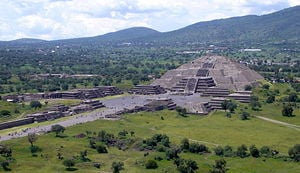

The city's broad central avenue, called "Avenue of the Dead" by the Aztecs, is flanked by impressive ceremonial architecture, including the immense Pyramid of the Sun (second largest in the New World) and the Pyramid of the Moon. Along the Avenue of the Dead are many smaller talud-tablero (stepped) platforms. The Aztecs believed these were tombs, inspiring the name of the avenue. Now they are known to be ceremonial platforms that were topped with temples.

Further down the Avenue of the Dead is the area known as the Citadel, containing the ruined Temple of the Feathered Serpent. This area was a large plaza surrounded by temples that formed the religious and political center of the city. The name "Citadel" was given to it by the Spanish, who mistakenly believed it was a fort.

Many of the rich and powerful Teotihuacános lived in palaces near the temples. The largest of these covers more than 3,947 square yards. Most of the common people lived in large apartment buildings spread across the city. Many of the buildings contained workshops that produced pottery and other goods.

The geographical layout of Teotihuacán is a good example of the Mesoamerican tradition of planning cities, settlements, and buildings as a representation of the Teotihuacáno view of the universe. Its urban grid is aligned to precisely 15.5º east of north. The Avenue of the Dead lines up with Cerro Gordo Mountain to the north of the Pyramid of the Moon.

History

Origins and foundation

The early history of Teotihuacán is quite mysterious, and the origin of its founders is debated. Today it is believed to have been first settled around 400 B.C.E. by refugees from the ancient city of Cuicuilco who fled from the volcanic activity which destroyed their homes. However, it did not develop into a major population center until around the beginning of the common era. For many years, archaeologists believed that Teotihuacán was built by the Toltec people, based on Aztec writings which attributed the site to the Toltecs. However, the Nahuatl (Aztec) word "Toltec" means "great craftsman" and may not always refer to the Toltec civilization. Archaeologists now believe that Teotihuacán predates the Toltec civilization, ruling them out as the city's founders.

The culture and architecture of Teotihuacán was also influenced by the Olmec people, who are considered to be the "mother civilization" of Mesoamerica. Some scholars have put forth the Totonac people as the founders of Teotihuacán, and the debate continues to this day. The earliest buildings at Teotihuacán date to about 200 B.C.E., and the largest pyramid, the Pyramid of the Sun, was completed by 100 C.E.

Center of influence

The city reached its zenith between 150 and 450 C.E., when it was the center of a powerful culture that dominated Mesoamerica, wielding power and influence comparable to ancient Rome. At its height the city covered eight square miles, and probably housed a population of over 150,000 people, possibly as many as 250,000. Various districts in the city housed people from across the Teotihuacáno empire that spread south as far as Guatemala. Yet, despite its power, notably absent from the city are fortifications and military structures. Teotihuacán had a major influence on Maya history, conquering several Maya centers, including Tikal, and influencing Maya culture.

The Teotihuacano style of architecture was a major contribution to Mesoamerican culture. The stepped pyramids that were prominent in Maya and Aztec architecture originated in Teotihuacán. This style of building was called "talud-tablero," where a rectangular panel (tablero) was placed over a sloping side (talud).

The city was a center of industry, home to many potters, jewelers, and craftsmen. Teotihuacán is also known for producing a great number of obsidian artifacts.

Unfortunately, no ancient Teotihuacáno non-ideographic texts exist, nor are they known to have a system of writing. However, mentions of the city in inscriptions from Maya cities show that Teotihuacán nobility traveled to and perhaps conquered local rulers as far away as Honduras. Maya inscriptions mention an individual nicknamed by scholars as "Spearthrower Owl," apparently the ruler of Teotihuacán who reigned for over 60 years and installed his relatives as rulers of Tikal and Uaxactún in Guatemala.

Most of what we infer about the culture at Teotihuacán comes from the murals that adorn the site and related ones, and from hieroglyphic inscriptions made by the Maya describing their encounters with Teotihuacáno conquerors.

Collapse

Sometime during the seventh or eighth centuries C.E., the city was sacked and burned. One theory is that the destruction resulted from the attacks of invaders, possibly the Toltecs. Opposing this view is a theory of a class-based uprising, based on the fact that the burning was limited primarily to the structures and dwellings associated with the ruling elites. The fact that population began to decline around 500-600 C.E. supports the internal unrest hypothesis, but is not inconsistent with the theory of invasion. The decline of Teotihucán has also been correlated with the droughts related to the climate changes of 535–536. This theory is supported by the archaeological remains that show a rise in the percentage of juvenile skeletons with evidence of malnutrition during the sixth century.

Other nearby centers like Cholula, Xochicalco, and Cacaxtla attempted to fill the powerful vacuum left by Teotihuacán's decline. Earlier, they may have aligned themselves against Teotihuacán in an attempt to reduce its influence and power. The art and architecture at these sites shows an interest in emulating Teotihuacán forms, but also a more eclectic mix of motifs and iconography from other parts of Mesoamerica, particularly the Maya region.

Teotihuacano culture

There is archaeological evidence that Teotihuacán was a multi-ethnic city, with distinct Zapotec, Mixtec, Maya, and what seem to be Nahua quarters. Scholar Terrence Kaufman presents linguistic evidence suggesting that an important ethnic group in Teotihuacán was of Totonacan and/or Mixe-Zoquean linguistic affiliation.[1]

The religion of Teotihuacán is similar to those of other Mesoamerican cultures. Many of the same gods were worshiped, including the Quetzalcoatl, the Feathered Serpent, and Tlaloc the Rain god. Teotihuacán was a major religious center, and its priests probably had a great deal of political power.

As with other Mesoamerican cultures, Teotihuacános practiced human sacrifice. Human bodies and animal sacrifices have been found during excavations of the pyramids at Teotihuacán; it is believed that when the buildings were expanded, sacrifices were made to dedicate the new building. The victims were probably enemy warriors captured in battle and then brought to the city to be ritually sacrificed so the city could prosper. Some were decapitated, some had their hearts removed, others were killed by being hit several times over the head, and some even buried alive. Animals that were considered sacred and represented mythical powers and military might were also buried alive in their cages: cougars, a wolf, eagles, a falcon, an owl, and even venomous snakes.

Archaeological site

Knowledge of the huge ruins of Teotihuacán was never lost. After the fall of the city, various squatters lived on the site. During Aztec times, the city was a place of pilgrimage and identified with the myth of Tollan, the place where the sun was created. Teotihuacán astonished the Spanish conquistadores during the Contact era. Today, it is one of the most noted archaeological attractions in Mexico.

Minor archaeological excavations were conducted in the nineteenth century, and in 1905 major projects of excavation and restoration began under archaeologist Leopoldo Batres. The Pyramid of the Sun was restored to celebrate the centennial of Mexican Independence in 1910. Major programs of excavation and restoration were carried out in 1960-1965 and 1980-1982. Recent projects at the Pyramid of the Moon and the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent have greatly expanded evidence of cultural practices at Teotihuacán. Today, Teotihuacán features museums and numerous reconstructed structures; thousands visit the site daily.

Gallery

Notes

- ↑ Terrence Kaufman, "Nawa linguistic prehistory" www.albany.edu. Retrieved March 16, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Coe, Michael D., Dean Snow, and Elizabeth Benson. Atlas of Ancient America (Cultural Atlas of). Facts on File, 1986. ISBN 0-816-01199-0

- Kaufman, Terrence. Nawa linguistic prehistory Mesoamerican Languages Documentation Project, 2001. Nawa linguistic prehistory. Retrieved March 16, 2008.

- Malmström, Vincent H. Architecture, Astronomy, and Calendrics in Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica in Journal for the History of Astronomy, vol. 9, pages 105–116, 1978 www.dartmouth.edu.

- Miller, Mary, and Karl Taube. The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya. Thames and Hudson, 1993. ISBN 0-500-05068-6

- Weaver, Muriel Porter. The Aztecs, Maya, and Their Predecessors: Archaeology of Mesoamerica, 3rd edition. Academic Press, 1993. ISBN 0-012-63999-0

External links

All links retrieved April 29, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.