Terracotta Army

| Mausoleum of the First Qin Emperor* | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| |

| State Party | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, iii, iv, vi |

| Reference | 441 |

| Region** | Asia-Pacific |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1987 (11th Session) |

| * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. ** Region as classified by UNESCO. | |

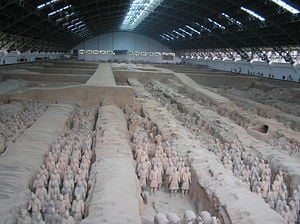

The Terracotta Army (Traditional Chinese: 兵馬俑; Simplified Chinese: 兵马俑; pinyin: bīngmǎ yǒng; literally "soldier and horse funerary statues") or Terracotta Warriors and Horses is a collection of 8,099 life-size Chinese terra cotta figures of warriors and horses located near the Mausoleum of the First Qin Emperor (Chinese: 秦始皇陵; pinyin: Qín Shǐhuáng líng). The figures were discovered in 1974 near Xi'an, Shaanxi province, China, by farmers drilling a water well. Three pits containing the warriors were excavated, and the first was opened to the public in 1979.

The warriors were intended to protect the emperor’s tomb and support him as he reigned over an empire in the afterlife. The terracotta figures are life-like and life-sized, varying in height, uniform and hairstyle according to their rank. They were painted with a colored lacquer finish and equipped with real weapons and armor. Each warrior has distinctive facial features and expressions, suggesting that they were modeled on real soldiers from the emperor’s army. After completion, the terracotta figures were placed in the pits outlined above in precise military formation according to rank and duty. They provide a wealth of information for military historians, and their existence is a testimony to the power and wealth of Qin Shi Huang the First Emperor of Qin. The site was listed by UNESCO in 1987 as a World Cultural Heritage Site.

Introduction

The Terracotta Army was buried with the Emperor of Qin (Qin Shi Huang) in 210-209 B.C.E. (he reigned over Qin from 247 B.C.E. to 221 B.C.E., and over unified China from 221 B.C.E. until his death in 210 B.C.E.). They were intended to protect the emperor’s tomb and support the Emperor Qin Shi Huangdi as he ruled over another empire in the afterlife, and are sometimes referred to as "Qin's Armies."

The Terracotta Army was discovered in March 1974 by local farmers drilling a water well 1,340 yards east of Emperor Qin Shi Huangdi’s burial mound, which is situated at the foot of Mount Lishan. Mount Lishan is also where the material to make the terracotta warriors originated. The burial complex lies about twenty miles east of Xi’an in Shaanxi Province in western China. Xi’an, formerly known as Chang’an, was the imperial capital of the Qin dynasty for several centuries. Pottery found by the farmers soon attracted the attention of archeologists, who quickly established beyond doubt that these artifacts were associated with the Qin Dynasty (211-206 B.C.E.).

The State Council authorized the building of a museum on the site in 1975, and the first pit was opened to the public on China's National Day, 1979. Three pits have been excavated and a large hall has been built to protect them and allow for public viewing. There are 8,009 life-size warriors, archers, and foot soldiers. The first pit, covering an area of 172,000 square feet, contains 6,000 figures facing east in battle formation, with war chariots at the back. The second pit, excavated in 1976, covers 64,500 square feet and contains one thousand warriors in the chariot cavalry corps, with horses and ninety lacquered wooden chariots. It was unveiled to the public in 1994. The third pit, which went on display in 1989, covers only 5,000 square feet and appears to be a command center, containing 68 figures of high-ranking officers, a war chariot, and four horses. A fourth pit remained empty; it is possible that the emperor died before it could be completed. In addition to the warriors, an entire man-made necropolis for the emperor has been excavated. Work is ongoing at the site.

Mausoleum

Construction of this mausoleum began in 246 B.C.E., when the 13-year-old Huangdi ascended the throne, and is believed to have taken 700,000 workers and craftsmen 38 years to complete. Qin Shi Huangdi was interred inside the tomb complex upon his death in 210 B.C.E.. According to the Grand Historian Sima Qian (145 - 90 B.C.E.)., the First Emperor was buried alongside large quantities of treasure and objects of craftsmanship, as well as a scale replica of the universe complete with gemmed ceilings representing the cosmos, and flowing mercury representing the great earthly bodies of water. Pearls were placed on the ceilings in the tomb to represent the stars and planets. Recent scientific analysis at the site has shown high levels of mercury in the soil of Mount Lishan, tentatively indicating that Sima Qian’s description of the site’s contents was accurate.

The tomb of Qin Shi Huangdi is near an earthen pyramid 76 meters tall and nearly 350 meters square, on the Huishui River at the foot of Lishan Mountain. Its location was carefully chosen according to the principles of feng shui. The tomb presently remains unopened; there are plans to seal off the area around it with a special tent-type structure to prevent corrosion from exposure to outside air.

Qin Shi Huangdi’s necropolis complex was constructed to serve as an imperial compound or palace. It comprises several offices, halls and other structures and is surrounded by a wall with gateway entrances. The remains of the craftsmen working in the tomb have been discovered within its confines; it is believed that they were sealed inside alive to keep them from divulging any secrets about its contents or the entrance. The compound was protected by the massive terracotta army interred nearby.

In July, 2007, it was determined, using remote sensing technology, that the mausoleum contains a 90-foot tall building built above the tomb, with four stepped walls, each having nine steps.[1]

Construction of the Warriors

The terracotta figures were manufactured both in workshops by government laborers, and also by local craftsmen. It is believed they were made in much the same way that terracotta drainage pipes were manufactured at the time, with specific parts manufactured and assembled after being fired, rather than the entire piece being crafted and fired at once.

The terracotta figures are life-like and life-sized. They vary in height, uniform and hairstyle in accordance with rank. The colored lacquer finish, molded faces, and real weapons and armor with which they were equipped created a realistic appearance. Each warrior has distinctive facial features and expressions, and it is believed that they were modeled on real soldiers. After completion, the terracotta figures were placed in the pits outlined above in precise military formation according to rank and duty. They provide a wealth of information for military historians, and their existence is a testimony to the power and wealth of the First Emperor of Qin. The site was listed by UNESCO in 1987 as a World Cultural Heritage Site.

Destruction

There is evidence of a large fire that burned the wooden structures once housing the Terracotta Army. The fire was described by Sima Qian, who describes how the tomb was raided by General Xiang Yu, less than five years after the death of the First Emperor, and how his army looted of the tomb and structures holding the Terracotta Army, stealing the weapons from the terracotta figures and setting fire to the necropolis, a blaze that lasted for three months. Despite this fire, however, much of the Terracotta Army still survives in various stages of preservation, surrounded by remnants of the burnt wooden structures.

Today, nearly two million people visit the site annually; almost one-fifth of these are foreigners. The Terracotta Army is not only an archaeological treasure, but is recognized the world over as an icon of China’s distant past and a monument to the power and military achievement of the First Emperor Qin Shi Huang.

In 1999, it was reported that pottery warriors were suffering from "nine different kinds of mold," caused by raised temperatures and humidity in the building which houses the soldiers, and the breath of tourists.[2] The South China Morning Post reported the figures have oxidized and become gray from being exposed to air, and that this oxidation may cause noses and hairstyles to disappear, and arms to fall off.[3] Chinese officials dismissed the claims.[4] In Daily Planet Goes to China, the Terracotta Warriors segment reported the Chinese scientists found soot on the surface of the statue, concluding that the pollution from coal-burning electricity plants was responsible for the decaying of the terracotta statues.

Terracotta Army Outside China

- Forbidden Gardens, a privately funded outdoor museum in Katy, Texas has 6,000 1/3 scale replica terra-cotta soldiers displayed in formation as they were buried in the 3rd century B.C.E. Several full-size replicas are included for scale, and replicas of weapons discovered with the army are shown in a separate Weapons Room. The museum's sponsor is a Chinese businessman whose goal is to share his country's history.

- China participated in the 1982 World's Fair for the first time since 1904, displaying four terra-cotta warriors and horses from the Mausoleum.

- In 2004, an exhibit of the terracotta warriors was featured at 2004 Universal Forum of Cultures in Barcelona. It later inaugurated the Cuarto Depósito Art Center at Madrid[5]. It consisted of ten warriors, four other big figures and other pieces (totalling 170) from the Qin and Han dinasties.

- Silent Warriors, 81 original artifacts including ten soldiers were on display in Malta at the Archaeological Museum in Valletta till the July 31, 2007.

- Twelve terra-cotta warriors, together with other figures excavated from the tomb, will move to the British Museum in London between September 2007 and April 2008.

Notes

- ↑ China's terracotta tomb site hides mystery building, Reuters UK, Sun Jul 1, 2007 4:58am BST. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ↑ World: Asia-Pacific Pollution threat to terracotta army. BBC, Wednesday, March 3, 1999 Published at 02:40 GMT. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ↑ Air pollution harms terracotta warriors. News in Science, ABC. Tuesday, 28 June 2005. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ↑ Is the terracotta army in danger?. DANWEI, Posted by Joel Martinsen, July 7, 2005 10:01 AM. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ↑ Los Guerreros de Xian llegan a Madrid, El Mundo, 28 September 2004. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Debainne-Francfort, Corrine. The Search for Ancient China. Harry N. Abrams Inc. Pub. 1999: 91-99. ISBN 0810928507 ISBN 9780810928503

- Dillon, Michael (ed.). China: A Cultural and Historical Dictionary Curzon Press, 1998: 196. ISBN 0700704388 ISBN 9780700704385 ISBN 0700704396 ISBN 9780700704392

- Ledderose, Lothar. "A Magic Army for the Emperor." in Ten Thousand Things: Module and Mass Production in Chinese Art (ed.). Lothar Ledderose, (Princeton UP, 2000): 51-73. ISBN 0691006695 ISBN 9780691006697 ISBN 0691009570 ISBN 9780691009575

- Perkins, Dorothy. Encyclopedia of China: The Essential Reference to China, Its History and Culture. Roundtable Press, 1999: 517-518. ISBN 0816026939 ISBN 9780816026937

External links

All links retrieved April 30, 2023.

- UNESCO description of the Mausoleum of the First Qin Emperor.

- The only museum outside China dedicated to Terracotta warriors - featured in Britain.

| |||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.