Timur

Tīmūr bin Taraghay Barlas (Chagatai Turkic): تیمور - Tēmōr, iron) (1336 – February 1405) was a fourteenth-century warlord of Turco-Mongol descent[1][2] Timur (timoor') or Tamerlane (tăm'urlān), (c.1336–1405), the Mongol conqueror, was born at Kesh, near Samarkand. Timur was a member of the Turkic Barlas clan of Mongols, conqueror of much of Western and central Asia, and founder of the Timurid Empire (1370–1405) in Central Asia and of the Timurid dynasty, which survived in some form until 1857. He is also known as Timur-e Lang which translates to Timur the Lame. He became lame after sustaining a leg injury as a child.

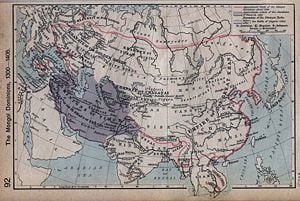

He ruled over an empire that extends in modern nations from south eastern Turkey, Syria, Iraq, Kuwait, Iran, through Central Asia encompassing part of Kazakhstan, Afghanistan, Russia, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, India, even approaching Kashgar in China.

After his marriage into thirteenth-century Mongol conqueror Genghis Khan's family, he took the name Timūr Gurkānī, Gurkān being the Persianized form of the original Mongolian word kürügän, "son-in-law." Alternative spellings of his name are: Temur, Taimur, Timur Lenk, Timur-i Leng, Temur-e Lang, Amir Timur, Aqsaq Timur, as well as the Latinized Tamerlane and Tamburlaine. Today, he is a figure of national importance in Uzbekistan whose conquests affected much of the cultural, social, and political development of the Eastern hemisphere.

Early Life

Timur was born in Transoxiana, near Kesh (an area now better known as Shahr-e Sabz), 'the green city,' situated some 50 miles south of Samarkand in modern Uzbekistan.

Timur placed much of his early legitimacy on his genealogical roots to the great Mongol conqueror Genghis Khan. What is known is that he was descended from the Mongol invaders who initially pushed westwards after the establishment of the Mongol Empire.

His father Taraghay was head of the tribe of Barlas, a nomadic Turkic-speaking tribe of Mongol origin that traced its origin to the Mongol commander Qarachar Barlas. Taraghay was the great-grandson of Qarachar Noyon and, distinguished among his fellow-clansmen as the first convert to Islam, Taraghay might have assumed the high military rank which fell to him by right of inheritance; but like his father Burkul he preferred a life of retirement and study. Taraghay would eventually retire to a Muslim monastery, telling his son that "the world is a beautiful vase filled with scorpions."

Under a paternal eye, the education of young Timur was such that at the age of 20 he had not only become adept in manly outdoor exercises, but had earned the reputation of being very literate and an attentive reader of the Qur'an. Like his father, Timur was a Muslim and may have been influenced by Sufism. At this period, according to the Memoirs (Malfu'at), he exhibited proofs of a tender and sympathetic nature, though these claims are generally now held to be spurious.

In addition, the spurious genealogy on his tombstone taking his descent back to Ali, and the presence of Shiites in his army led some observers and scholars to call him a Shiite. However, his official religious counselor was the Hanafite scholar Abd alJabbar Khwarazmi. There is evidence that he had converted to be Nusayri under the influence of Sayyed Barakah, a Nusayri leader from Balkh, who was a mentor of his. He also constructed one of his finest buildings at the tomb of Ahmed Yesevi, an influential Turkic Sufi saint who was doing most to spread Sunni Islam among the nomads.

Military leader

In about 1360 Timur gained prominence as a military leader. He took part in campaigns in Transoxania with the khan of Chagatai, a descendant of Genghis Khan. His career for the next ten or eleven years may be thus briefly summarized from the Memoirs. Allying himself both in cause and by family connection with Kurgan, the dethroner and destroyer of Volga Bulgaria, he was to invade Khorasan at the head of a thousand horsemen. This was the second military expedition which he led, and its success led to further operations, among them the subjection of Khwarizm and Urganj.

After the murder of Kurgan the disputes which arose among the many claimants to sovereign power were halted by the invasion of Tughluk Timur of Kashgar, another descendant of Genghis Khan. Timur was dispatched on a mission to the invader's camp, the result of which was his own appointment to the head of his own tribe, the Barlas, in place of its former leader Hajji Beg.

The exigencies of Timur's quasi-sovereign position compelled him to have recourse to his formidable patron, whose reappearance on the banks of the Syr Darya created a consternation not easily allayed. The Barlas were taken from Timur and entrusted to a son of Tughluk, along with the rest of Mawarannahr; but he was defeated in battle by the bold warrior he had replaced at the head of a numerically far inferior force.

Rise to power

Tughluk's death facilitated the work of reconquest, and a few years of perseverance and energy sufficed for its accomplishment, as well as for the addition of a vast extent of territory. During this period Timur and his brother-in-law Husayn, at first fellow fugitives and wanderers in joint adventures full of interest and romance, became rivals and antagonists. At the close of 1369 Husayn was assassinated and Timur, having been formally proclaimed sovereign at Balkh, mounted the throne at Samarkand, the capital of his dominions. This event was recorded by Marlowe in his famous work Tamburlaine the Great [3]:

| “ | Then shall my native city, Samarcanda… Be famous through the furthiest continents, |

” |

It is notable that Timur never claimed for himself the title of khan, styling himself amir and acting in the name of the Chagatai ruler of Transoxania. Timur was a military genius but lacking in political sense. He tended not to leave a government apparatus behind in lands he conquered, and was often faced with the need to conquer such lands again after inevitable rebellions.

Period of expansion

Until his death, Timur spent the next 35 years in various wars and expeditions. Timur not only consolidated his rule at home by the subjugation of his foes, but sought extension of territory by encroachments upon the lands of foreign potentates. His conquests to the west and north-west led him among the Mongols of the Caspian Sea and to the banks of the Ural and the Volga. Conquests in the south and south-West encompassed almost every province in Persia, including Baghdad, Karbala and Kurdistan.

One of the most formidable of his opponents was Tokhtamysh who, after having been a refugee at the court of Timur, became ruler both of the eastern Kipchak and the Golden Horde and quarrelled with Timur over the possession of Khwarizm. Timur supported Tokhtamysh against Russians and Tokhtamysh, with armed support by Timur, invaded Russia and in 1382 captured Moscow. After the death of Abu Sa'id (1335), ruler of the Ilkhanid Dynasty, there was a power vacuum in the Persia. In 1383 Timur started the military conquest of Persia. Timur captured Herat, Khorasan and all eastern Persia to 1385.

In the meantime, Tokhtamysh, now khan of the Golden Horde, turned against Timur and invaded Azerbaijan in 1385. It was not until 1395, in the battle of Kur River, that the power of Tokhtamysh was finally broken, after a titanic struggle between the two monarchs. In this war, Timur led an army of over 100,000 men north for about 500 miles into the uninhabited steppe, then west about 1000 miles, advancing in a front more than 10 miles wide. Tokhtamysh's army finally was cornered against the Volga River near Orenburg and destroyed. During this march, Timur's army got far enough north to be in a region of very long summer days, causing complaints by his Muslim soldiers about keeping a long schedule of prayers in such northern regions. Timur led a second campaign against Tokhtamysh via an easier route through the Caucasus, and Timur destroyed Sarai and Astrakhan, and wrecked the Golden Horde's economy based on Silk Road trade.

India

In 1398 Timur, informed about civil war in India (started in 1394), began war against the Muslim Ruler in Delhi. He crossed the Indus River at Attock on September 24. The capture of towns and villages was very often accompanied by their destruction and the massacre of their inhabitants. On his way to Delhi he met fierce resistance put up by the Governor of Meerut. Timur (though very much impressed by Ilyaas Awan's bravery) approached Delhi to meet with the armies of the Emperor, Sultan Nasir-u-Din Mehmud of Tughlaq Dynasty, who was already weak due to a fight for power in the Royal Family. The Sultan's army was easily defeated and destroyed on December 17 1394. Timur entered Delhi and the city was sacked, destroyed, and left in a mass of ruins. Before the battle for Delhi, Timur executed more than 50,000 captives, and after the sack of Delhi almost all inhabitants who were not killed were captured and deported. It is said that the devastation of Delhi was not Timur's intent, but that his horde could simply not be controlled after entering the city gates. However, some historians have stated that he told his armies they could have free rein over Delhi.

Timur left Delhi in approximately January 1399. In April 1399 he was back in his own capital beyond the Oxus (Amu Darya). An immense quantity of spoils was conveyed from India. According to Ruy Gonzáles de Clavijo, 90 captured elephants were employed merely to carry stones from certain quarries to enable the conqueror to erect a mosque at Samarkand, probably the enormous Bibi-Khanym Mosque.

Fall of Timur

During the war of Timur with the Panchayat armies in India, The Deputy Commander Harveer Gulia, along with 25,000 warriors of the Panchayat army, made a fierce attack on a large group of Timur's horsemen, and a fierce battle ensued where arrows and spears were used (There over 2,000 hill archers joined the Panchayat Army. One arrow pierced Timur's hand. Timur was in the army of horsemen. Harveer Singh Gulia charged ahead like a lion, and hit Timur on his chest with a spear, and he was about to fall under his horse, when his commander Khijra, saved him and separated him from the horse. (Timur eventually died from this wound when he reached Samarkand). The spearmen and swordsmen of the enemy leapt on the Harveer Singh Gulia, and he fainted from the wounds he received and fell. At that very time, the Supreme Commander Jograj Singh Gujar, with 22,000 Mulls (warriors) attacked the enemy and killed 5000 horsemen. Jograj Singh himself with his own hands lifted the unconscious Harveerr Singh Gulia and brought him to the camp. A few hours later, Harveer Singh was killed. Sikhs regard him as a martyr.

This attack is confirmed from following quotation from the book of Timur-lung:

| “ | "Happy"? mused Kurgan (a vassal of Khakhan in Persia-750 A. Hijri). There are pleasures but no happiness. I remember well when Taragai (father of Tamerlane or Timur-lung) and I campained together and enjoyed together the pleasures of victory - and the pains. He was with me when I caught a Jat arrow here. He pointed to the flap over his vacant eye socket.[4] [5] | ” |

Last campaigns and death

Before the end of 1399 Timur started a war with Bayezid I, sultan of the Ottoman Empire, and the Mamluk sultan of Egypt. Bayezid began annexing the territory of Turkmen and Muslim rulers in Anatolia. As Timur claimed suzerainity over the Turkmen rulers, they took refuge behind him. Timur invaded Syria, sacked Aleppo, and captured Damascus after defeating the Mamluk's army. The city's inhabitants were massacred, except for the artisans who were deported to Samarkand. This led to Tamarlane's being publicly declared an enemy of Islam.

He invaded Baghdad in June 1401. After the capture of the city, 20,000 of its citizens were massacred. Timur ordered that every soldier should return with at least two severed human heads to show him (many warriors were so scared they killed prisoners captured earlier in the campaign just to ensure they had heads to present to Timur). In 1402, Timur invaded Anatolia and defeated Bayezid in the Battle of Ankara on July 20, 1402. Bayezid was captured in battle and subsequently died in captivity, initiating the 12-year Ottoman Interregnum period. Timur's stated motivation for attacking Bayezid and the Ottoman Empire was the restoration of Seljuq authority. Timur saw the Seljuks as the rightful rulers of Anatolia as they had been granted rule by Mongol conquerors, illustrating again Timur's interest with Genghizid legitimacy.

By 1368, the Ming had driven the Mongols out of China. The first Ming Emperor Hongwu Emperor demanded, and got, many Central Asian states to pay homage to China as the political heirs to the former House of Kublai. Timur more than once sent to the Ming Government gifts which could have passed as tribute, at first not daring to defy the economic and military might of the Middle Kingdom.

Timur wished to restore the Mongol Empire, and eventually planned to conquer China. In December 1404, Timur started military expeditions against the Ming Dynasty of China, but he was attacked by fever and plague when encamped on the farther side of the Sihon (Syr-Daria) and died at Atrar (Otrar) in mid-February 1405. His scouts explored Mongolia before his death, and the writing they carved on trees in Mongolia's mountains could still be seen even in the twentieth century.

Of Timur's four sons, two (Jahangir and Umar Shaykh) predeceased him. His third son, Miran Shah, died soon after Timur, leaving the youngest son, Shah Rukh. Although his designated successor was his grandson Pir Muhammad b. Jahangir, Timur was ultimately succeeded in power by his son Shah Rukh. His most illustrious descendant Babur founded the Mughal Empire and ruled over most of North India. Babur's descendants, Akbar, Jahangir, Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb, expanded the Mughal Empire to most of the Indian subcontinent along with parts of Afghanistan.

Markham, in his introduction to the narrative of Clavijo's embassy, states that his body "was embalmed with musk and rose water, wrapped in linen, laid in an ebony coffin and sent to Samarkand, where it was buried." His tomb, the Gur-e Amir, still stands in Samarkand. Timur had carried his victorious arms on one side from the Irtish and the Volga to the Persian Gulf, and on the other from the Hellespont to the Ganges River.

Contributions to the arts

Timur became widely known as a patron to the arts. Much of the architecture he commissioned still stands in Samarkand, now in present-day Uzbekistan. He was known to bring the most talented artisans from the lands he conquered back to Samarkand. And he is credited with often giving them a wide latitude of artistic freedom to express themselves.

According to legend, Omar Aqta, Timur's court calligrapher, transcribed the Qur'an using letters so small that the entire text of the book fit on a signet ring. Omar also is said to have created a Qur'an so large that a wheelbarrow was required to transport it. Folios of what is probably this larger Qur'an have been found, written in gold lettering on huge pages.

Timur was also said to have created Tamerlane Chess, a variant of shatranj (also known as medieval chess) played on a larger board with several additional pieces and an original method of pawn promotion.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Timur's generally recognized biographers are Ali Yazdi, commonly called Sharaf ud-Din, author of the Persian Zafarnāma (Persian ظفرنامه), translated by Peter de la Croix in 1722, and from French into English by J. Darby in the following year; and Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Abdallah, al-Dimashiqi, al-Ajami, commonly called Ahmad Ibn Arabshah, author of the Arabic Aja'ib al-Maqdur, translated by the Dutch Orientalist Colitis in 1636. In the work of the former, as Sir William Jones remarks, "the Tatarian conqueror is represented as a liberal, benevolent and illustrious prince," in that of the latter he is "deformed and impious, of a low birth and detestable principles." But the favorable account was written under the personal supervision of Timur's grandson, Ibrahim, while the other was the production of his direst enemy.

Among less reputed biographies or materials for biography may be mentioned a second Zafarnāma, by Nizām al-Dīn Shāmī, stated to be the earliest known history of Timur, and the only one written in his lifetime. Timur's purported autobiography, the Tuzuk-i Temur ("Institutes of Temur") is a later fabrication although most of the historical facts are accurate[1].

More recent biographies include Justin Marozzi's Tamerlane: Sword of Islam, Conqueror of the World (Da Capo Press 2006), and Roy Stier's Tamerlane: The Ultimate Warrior (Bookpartners 1998).

Exhumation

Timur's body was exhumed from his tomb in 1941 by the Russian anthropologist Mikhail M. Gerasimov. He found that Timur's facial characteristics conformed to that of Mongoloid features, which he believed, in some part, supported Timur's notion that he was descended from Genghis Khan. He also confirmed Timur's lameness. Gerasimov was able to reconstruct the likeness of Timur from his skull.

Famously, a curse has been attached to opening Timur's tomb.[6] In the year of Timur's death, a sign was carved in Timur's tomb warning that whoever would dare disturb the tomb would bring demons of war onto his land. Gerasimov's expedition opened the tomb on June 19, 1941. Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany, began three days later on June 22, 1941. Shortly after Timur's skeleton and that of Ulugh Beg, his grandson, were reinterred with full Islamic burial rites in 1942, the Germans surrendered at Stalingrad.

The legend of Tamerlane's curse features prominently in the second book of the 2006 Russian Science Fiction trilogy by Sergei Lukyanenko, Day Watch.

A Legacy in Fiction

- There is a popular Irish Reel entitled Timour the Tartar.

- Timur Lenk was the subject of two plays (Tamburlaine the Great, Parts I and II) by English playwright Christopher Marlowe.

- Bob Bainborough portrayed Tamerlane in an episode of History Bites.

- George Frideric Handel made Timur Lenk the title character of his Tamerlano (HWV 18), an Italian language opera composed in 1724, based on the 1675 play Tamerlan ou la mort de Bajazet by Jacques Pradon.

- Edgar Allan Poe's first published work was a poem entitled "Tamerlaine."

- German-Jewish writer and social critic Kurt Tucholsky, under the pen name of Theobald Tiger, wrote the lyrics to a cabaret song about Timur in 1922, with the lines

- Mir ist heut so nach Tamerlan zu Mut—

- ein kleines bisschen Tamerlan wär gut

which roughly translates as "I feel like Tamerlane today, a little bit of Tamerlane would be nice." The song was an allegory about German militarism, as well as a wry commentary on German fears of "Bolshevism" and the "Asiatic hordes from the East."

- He is referred to in the poem "The City of Orange Trees" by Dick Davis. The poem is about an opulent society and the cyclic nature of zeal, prosperity and demise in civilization.

- Tamerlane features prominently in the short story Lord of Samarcand by Robert E. Howard which features a completely fictional account of his last campaign and death.

- In the Nintendo GameCube video game Eternal Darkness, Pious Augustus recites a speech echoing Tamerlane's actual speech after sacking Damascus, implying that Tamerlane was the masked warlord.

- In Microsoft's Age of Empires II, Tamerlane is a hero available only in the Map Editor.

- The alternate history novel The Years of Rice and Salt by Kim Stanley Robinson portrays a Timur whose last campaign is significantly different from the historical truth.

- There is a chapter in the Shame of Man (1994) Geodessey series by Piers Anthony, which imagines one of the main characters as an advisor Tamerlane.

Legacy

Timur's legacy is a mixed one, for while Central Asia blossomed, some say even peaked, under his reign, other places such as Baghdad, Damascus, Delhi and other Arab, Persian, Indian and Turkic cities were sacked and destroyed, and many thousands of people were slaughtered brutally. Thus, while Timur remains a hero of sorts in Central Asia, he is vilified by many in Arab, Persian and Indian societies. At the same time, many Western Asians still do name their children after him, while Persian literature calls him "Teymour, Conqueror of the World" (Persian: تیمور جهانگير).

Notes

This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 B.F. Manz, "Tīmūr Lang," in Encyclopaedia of Islam, Online Edition, 2006

- ↑ The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, "Timur," 6th ed., Columbia University Press

- ↑ Mark Dickens, Marlowe "The Life of Timur" The Life of Timur oxuscom. retrieved 10 July 2007

- ↑ Cothburn O'Neal. Conquest of Tamerlane. (Avon, 1952. ASIN: B000PM1IG8), 29

- ↑ Mangal sen Jindal. (1992) History of Origin of Some Clans in India, (with special Reference to Jats) (New Delhi: Sarup & Sons, 4378/4B, Ansari Road, Darya Ganj, ISBN 8185431086), 48

- ↑ S. Z. Ahmed. Twilight on the Silk Road. (Chapel Hill, NC: A.E.R. Publications, 1985 ISBN 9781570872815), 23.

References

- Ahmed, S. Z. Twilight on the Silk Road. Chapel Hill, NC: A.E.R. Publications, 1985 ISBN 9781570872815

- Grousset, René. The Empire of the Steppes; A History of Central Asia. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1970 ISBN 9780813506272

- Jindal, Mangal Sen. History of Origin of Some Clans in India, (with special Reference to Jats). New Delhi: Sarup & Sons, Ansari Road, Darya Ganj, 1992. ISBN 8185431086

- Manz, Beatrice Forbes. The Rise and Rule of Tamerlane. Cambridge studies in Islamic civilization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989 ISBN 9780521345958

- Marlowe, Christopher, and John Davies Jump. Tamburlaine the Great, Parts 1 and 2. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1967.

- Marozzi, Justin. Tamerlane: Sword of Islam, Conqueror of the World. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2006 ISBN 9780306814655

- O'Neal, Cothburn. Conquest of Tamerlane. Avon, 1952. ASIN: B000PM1IG8

- Stier, Roy. Tamerlane: The Ultimate Warrior. Bookpartners, 1998. ISBN 1885221770

External links

All links retrieved April 30, 2023.

- Memoir of the Emperor Timur (Malfuzat-i Timuri) Timur's memoirs on his invasion of India.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.