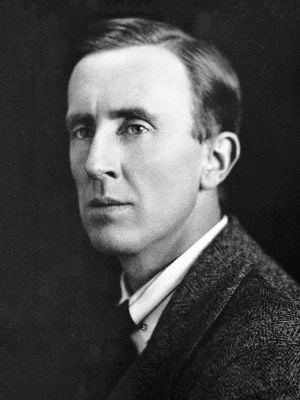

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien Order of the British Empire (January 3, 1892 – September 2, 1973) was a British writer and university professor who is best known as the author of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. He was an Oxford professor of Anglo-Saxon language (1925 to 1945) and English language and literature (1945 to 1959). He was a strongly committed Roman Catholic. Tolkien was a close friend of C. S. Lewis; they were both members of the informal literary discussion group known as the "Inklings."

Tolkien used fantasy in the same way fabulists have used folk and fairy tales, to tell stories that contain timeless truths, but like his close friend, C. S. Lewis, he infused them with an essentially Christian message. His works address the inner struggle of good and evil within each of us. The hero is not really the lords or wizards, but an ordinary person who is faced with a choice in every moment whether to follow the courageous path that serves the public good or succumb to the temptation to save himself.

In addition to The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien's published fiction includes The Silmarillion and other posthumously published books about what he called a legendarium, a connected body of tales, fictional histories, invented languages, and other literary essays about an imagined world called Arda, and Middle-earth (from middangeard, the lands inhabitable by Men) in particular, loosely identified as an 'alternative' remote past of our own world. Most of these works were compiled from Tolkien's notes by his son Christopher Tolkien.

The enduring popularity and influence of Tolkien's works have established him as the "father of modern fantasy literature." Tolkien's other published fiction includes stories not directly related to the legendarium, some of them originally told to his children.

Biography

The Tolkien family

As far as is known, most of Tolkien's paternal ancestors were craftsmen. The Tolkien family had its roots in Saxony (Germany), but had been living in England since the eighteenth century, becoming "quickly and intensely English".[1] The surname Tolkien is Anglicized from Tollkiehn (i.e. German tollkühn, "foolhardy"; the etymological English translation would be dull-keen, a literal translation of oxymoron). The surname Rashbold given to two characters in Tolkien's The Notion Club Papers is a pun on this.[2]

Tolkien's maternal grandparents, John and Edith Jane Suffield, lived in Birmingham and owned a shop in the city center. The Suffield family had had a business in a building called Lamb House since 1812. From 1812 William Suffield ran a book and stationery shop there; Tolkien's great-grandfather, also John Suffield, was there from 1826 with a drapery and hosiery business.

Childhood

Tolkien was born on January 3, 1892, in Bloemfontein in the Orange Free State (now Free State Province, South Africa), to Arthur Reuel Tolkien (1857–1896), an English bank manager, and his wife Mabel, née Suffield (1870–1904). Tolkien had one sibling, his younger brother, Hilary Arthur Reuel, who was born on February 17, 1894.[3]

While living in Africa he was bitten by a baboon spider in the garden, an event which would have later parallels in his stories. Dr. Thornton S. Quimby cared for the ailing child after the rather nasty spider bite, and it is occasionally suggested that Doctor Quimby was an early model for characters such as Gandalf the Grey.[4] When he was three, Tolkien went to England with his mother and brother on what was intended to be a lengthy family visit. His father, however, died in South Africa of rheumatic fever before he could join them.[5] This left the family without an income, so Tolkien's mother took him to live with her parents in Stirling Road, Birmingham. Soon after, in 1896, they moved to Sarehole (now in Hall Green), then a Worcestershire village, later annexed to Birmingham.[6] He enjoyed exploring Sarehole Mill and Moseley Bog and the Clent Hills and Malvern Hills, which would later inspire scenes in his books along with other Worcestershire towns and villages such as Bromsgrove, Alcester and Alvechurch and places such as his aunt's farm of Bag End, the name of which would be used in his fiction.[7]

Mabel tutored her two sons, and Ronald, as he was known in the family, was a keen pupil.[8] She taught him a great deal of botany, and she awakened in her son the enjoyment of the look and feel of plants. Young Tolkien liked to draw landscapes and trees. But his favorite lessons were those concerning languages, and his mother taught him the rudiments of Latin very early.[9] He could read by the age of four, and could write fluently soon afterwards. His mother got him lots of books to read. He disliked Treasure Island and The Pied Piper. He thought Alice's Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll was amusing, but also thought that Alice's adventures in it were disturbing. But he liked stories about Native Americans, and also the fantasy works by George MacDonald.[10] He attended King Edward's School, Birmingham and, while a student there, helped "line the route" for the coronation parade of King George V, being posted just outside the gates of Buckingham Palace.[11] He later attended St. Philip's School and Exeter College, Oxford.

His mother converted to Roman Catholicism in 1900 despite vehement protests by her Baptist family who then suspended all financial assistance to her. She died of complications due to diabetes in 1904, when Tolkien was 12, at Fern Cottage in Rednal, which they were then renting. For the rest of his life Tolkien felt that she had become a martyr for her faith, which had a profound effect on his own Catholic beliefs.[12] Tolkien's devout faith was significant in the conversion of C. S. Lewis to Christianity, though Tolkien was greatly disappointed that Lewis chose to return to the Anglicanism of his upbringing.[13]

During his subsequent orphanhood he was brought up by Father Francis Xavier Morgan of the Birmingham Oratory in the Edgbaston area of Birmingham. He lived there in the shadow of Perrott's Folly and the Victorian tower of Edgbaston Waterworks, which may have influenced the images of the dark towers within his works. Another strong influence was the romantic medievalist paintings of Edward Burne-Jones and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood; the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery has a large and world-renowned collection of works and had put it on free public display from around 1908.

Youth

Tolkien met and fell in love with Edith Mary Bratt, three years his senior, at the age of 16. Father Francis forbade him from meeting, talking, or even corresponding with her until he was 21. He obeyed this prohibition to the letter.[14]

In 1911, while they were at King Edward's School, Birmingham, Tolkien and three friends, Rob Gilson, Geoffrey Smith and Christopher Wiseman, formed a semi-secret society which they called "the T.C.B.S.," the initials standing for "Tea Club and Barrovian Society," alluding to their fondness of drinking tea in Barrow's Stores near the school and, illicitly, in the school library.[15] After leaving school, the members stayed in touch, and in December 1914, they held a "Council" in London, at Wiseman's home. For Tolkien, the result of this meeting was a strong dedication to writing poetry.

In the summer of 1911, Tolkien went on holiday in Switzerland, a trip that he recollects vividly in a 1968 letter,[16] noting that Bilbo Baggins' journey across the Misty Mountains ("including the glissade down the slithering stones into the pine woods") is directly based on his adventures as their party of 12 hiked from Interlaken to Lauterbrunnen, and on to camp in the moraines beyond Mürren. Fifty-seven years later, Tolkien remembers his regret at leaving the view of the eternal snows of Jungfrau and Silberhorn ("the Silvertine (Celebdil) of my dreams"). They went across the Kleine Scheidegg on to Grindelwald and across the Grosse Scheidegg to Meiringen. They continued across the Grimsel Pass and through the upper Valais to Brig, Switzerland, and on to the Aletsch glacier and Zermatt.

On the evening of his twenty-first birthday, Tolkien wrote to Edith a declaration of his love and asked her to marry him. She replied saying that she was already engaged but had done so because she had believed Tolkien had forgotten her. The two met up and beneath a railway viaduct renewed their love; Edith returned her ring and chose to marry Tolkien instead.[17] Following their engagement Edith converted to Catholicism at Tolkien's insistence.[18] They were engaged in Birmingham, in January 1913, and married in Warwick, England, on March 22, 1916.

After graduating from the University of Oxford (where he was a member of Exeter College) with a first-class degree in English language in 1915, Tolkien joined the British Army effort in World War I and served as a second lieutenant in the eleventh battalion of the Lancashire Fusiliers.[19] His battalion was moved to France in 1916, where Tolkien served as a communications officer during the Battle of the Somme (1916) until he came down with trench fever on October 27, 1916 and was moved back to England on November 8, 1916.[20] Many of his close friends, including Gilson and Smith of the T.C.B.S., were killed in the war. During his recovery in a cottage in Great Haywood, Staffordshire, England, he began to work on what he called The Book of Lost Tales, beginning with The Fall of Gondolin. Throughout 1917 and 1918 his illness kept recurring, but he had recovered enough to do home service at various camps, and was promoted to lieutenant. When he was stationed at Kingston upon Hull, one day he and Edith went walking in the woods at nearby Roos, and Edith began to dance for him in a clearing among the flowering hemlock: "We walked in a wood where hemlock was growing, a sea of white flowers".[21] This incident inspired the account of the meeting of Beren and Lúthien, and Tolkien often referred to Edith as his Lúthien.[22]

Career

Tolkien's first civilian job after World War I was at the Oxford English Dictionary, where he worked mainly on the history and etymology of words of Germanic origin beginning with the letter W.[23] In 1920 he took up a post as Reader in English language at the University of Leeds, and in 1924 was made a professor there, but in 1925 he returned to Oxford as a professor of Anglo-Saxon at Pembroke College, Oxford.

During his time at Pembroke, Tolkien wrote The Hobbit and the first two volumes of The Lord of the Rings. He also assisted Sir Mortimer Wheeler in the unearthing of a Roman Asclepieion at Lydney Park, Gloucestershire, in 1928.[24] Of Tolkien's academic publications, the 1936 lecture "Beowulf: the Monsters and the Critics" had a lasting influence on Beowulf research.[25] Lewis E. Nicholson noted that the article Tolkien wrote about Beowulf is "widely recognized as a turning point in Beowulfian criticism," noting that Tolkien established the primacy of the poetic nature of the work as opposed to the purely linguistic elements.[26] He also revealed in his famous article how highly he regarded Beowulf; "Beowulf is among my most valued sources…" And indeed, there are many influences of Beowulf found in the Lord of the Rings.[27] When Tolkien wrote, the consensus of scholarship deprecated Beowulf for dealing with childish battles with monsters rather than realistic tribal warfare; Tolkien argued that the author of Beowulf was addressing human destiny in general, not as limited by particular tribal politics, and therefore the monsters were essential to the poem. (Where Beowulf does deal with specific tribal struggles, as at Finnesburgh, Tolkien argued firmly against reading in fantastic elements.)[28]

In 1945, he moved to Merton College, Oxford, becoming the Merton Professor of English Language and Literature, in which post he remained until his retirement in 1959. Tolkien completed The Lord of the Rings in 1948, close to a decade after the first sketches. During the 1950s, Tolkien spent many of his long academic holidays at the home of his son John Francis in Stoke-on-Trent. Tolkien had an intense dislike for the side effects of industrialization which he considered a "devouring of the English countryside." For most of his adult life, he eschewed automobiles, preferring to ride a bicycle. This attitude is perceptible from some parts of his work such as the forced industrialization of The Shire in The Lord of the Rings.

W. H. Auden was a frequent correspondent and long-time friend of Tolkien's, initiated by Auden's fascination with The Lord of the Rings: Auden was among the most prominent early critics to praise the work. Tolkien wrote in a 1971 letter, "I am […] very deeply in Auden's debt in recent years. His support of me and interest in my work has been one of my chief encouragements. He gave me very good reviews, notices and letters from the beginning when it was by no means a popular thing to do. He was, in fact, sneered at for it.".[29]

Tolkien and Edith had four children: Rev. John Francis Reuel (November 17, 1917 – January 22, 2003), Michael Hilary Reuel (October 1920– 1984), Christopher John Reuel (b. 1924 -) and Priscilla Anne Reuel (b. 1929-).

Retirement and old age

During his life in retirement, from 1959 up to his death in 1973, Tolkien increasingly turned into a figure of public attention and literary fame. The sale of his books was so profitable that he regretted he had not taken early retirement.[30] While at first he wrote enthusiastic answers to reader inquiries, he became more and more suspicious of emerging Tolkien fandom, especially among the hippie movement in the United States.[31] In a 1972 letter he deplores having become a cult-figure, but admits that

even the nose of a very modest idol (younger than Chu-Bu and not much older than Sheemish) cannot remain entirely untickled by the sweet smell of incense![32]

Fan attention became so intense that Tolkien had to take his phone number out of the public directory, and eventually he and Edith moved to Bournemouth at the south coast. Tolkien was awarded the Order of the British Empire by Queen Elizabeth II at Buckingham Palace on March 28, 1972. His medal was stolen from his room later that night. The medal was returned much later, but the thief was never identified.

Edith Tolkien died on November 29, 1971, at the age of 82, and Tolkien had the name Lúthien engraved on the stone at Wolvercote Cemetery, Oxford. When Tolkien died 21 months later on September 2, 1973, at the age of 81, he was buried in the same grave, with Beren added to his name, so that the engravings now read:

- Edith Mary Tolkien, Lúthien, 1889–1971

- John Ronald Reuel Tolkien, Beren, 1892–1973

Posthumously named after Tolkien are the Tolkien Road in Eastbourne, East Sussex, and the asteroid 2675 Tolkien. Tolkien Way in Stoke-on-Trent is named after Tolkien's son, Fr. John Francis Tolkien, who was the priest in charge at the nearby Roman Catholic Church of Our Lady of the Angels and Saint Peter in Chains.[33]

Views

Tolkien was a devout Roman Catholic, and in his religious and political views he was mostly conservative, in the sense of favoring established conventions and orthodoxies over innovation and modernization. He was instrumental in the conversion of C.S. Lewis from atheism to Christianity, but was disappointed that Lewis returned to the Anglican church rather than becoming a Roman Catholic. Tolkien became supportive of Francisco Franco during the Spanish Civil War when he learned the republicans were destroying churches and killing priests and nuns.[34] He believed that Hitler was less dangerous than the Soviets: he wrote in a letter during the Munich Crisis that he believed that the Soviets were ultimately responsible for the problems and that they were trying to play the British and the French against Hitler.[35]

Though the perception of Tolkien as a racist or racialist have been a matter of scholarly discussion[36], statements made by Tolkien during his lifetime would seem to disprove such accusations. He regarded Nazi anti-Semitism as "pernicious and unscientific".[37] He also called the "treatment of color" (apartheid) in his birthplace South Africa horrifying, and spoke out against it in a valedictory address to the University of Oxford in 1959.[38]

Tolkien, having lost most of his friends in the trenches of World War I, was opposed to war in general, stating near the end of the war that the Allies were no better than their opponents, behaving like Orcs in their calls for a complete destruction of Germany. He was horrified by the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, referring to its creators as 'lunatics' and 'babel builders.'[39] He also was known to be forever embittered towards Nazism for appropriating the Germanic heritage which he had dedicated his life to studying and preserving, and perverting it to fit their own bigoted model of Aryan racial supremacy, a school of thought to which he had never subscribed, and which he surmised would forever taint Germanic culture by association.

His writings also evidence a strong respect for nature, and he wrote disparagingly of the wanton destruction of forests and wildlife.

Tolkien, in a letter to his son, once described himself as anarchist, or rather anarcho-monarchist. In the letter he briefly described anarchy as "philosophically understood, meaning abolition of control not whiskered men with bombs"[40]

Writing

Beginning with The Book of Lost Tales, written while recuperating from illness during World War I, Tolkien devised several themes that were reused in successive drafts of his legendarium. The two most prominent stories, the tales of Beren and Lúthien and that of Túrin, were carried forward into long narrative poems (published in The Lays of Beleriand). Tolkien wrote a brief summary of the legendarium these poems were intended to represent, and that summary eventually evolved into The Silmarillion, an epic history that Tolkien started three times but never published. It was originally to be published along with the Lord of the Rings, but printing costs were very high in the post-war years, resulting in the Lord of the Rings being published in three volumes.[41] The story of this continuous redrafting is told in the posthumous series The History of Middle-earth. From around 1936, he began to extend this framework to include the tale of The Fall of Númenor, which was inspired by the legend of Atlantis.

Tolkien was strongly influenced by English history and legends which he often confessed his love for, but he also drew influence from Scottish and Welsh history and legends as well from many other European countries, namely Scandinavia and Germany. He was also influenced by Anglo-Saxon literature, Germanic and Norse mythologies, Finnish mythology and the Bible.[42] The works most often cited as sources for Tolkien's stories include Beowulf, the Kalevala, the Poetic Edda, the Volsunga saga and the Hervarar saga.[43] Tolkien himself acknowledged Homer, Sophocles, and the Kalevala as influences or sources for some of his stories and ideas.[44] His borrowings also came from numerous Middle English works and poems. A major philosophical influence on his writing is King Alfred's Anglo-Saxon version of Boethius' Consolation of Philosophy known as the Lays of Boethius.[45] Characters in The Lord of the Rings such as Frodo Baggins, Treebeard, and Elrond make noticeably Boethian remarks. Also, Catholic theology and imagery played a part in fashioning his creative imagination, suffused as it was by his deeply religious spirit.[46]

In addition to his mythopoetic compositions, Tolkien enjoyed inventing fantasy stories to entertain his children.[47] He wrote annual Christmas letters from Father Christmas for them, building up a series of short stories (later compiled and published as The Father Christmas Letters). Other stories included Mr. Bliss, Roverandom, Smith of Wootton Major, Farmer Giles of Ham and Leaf by Niggle. Roverandom and Smith of Wootton Major, like The Hobbit, borrowed ideas from his legendarium. Leaf by Niggle appears to be an autobiographical allegory, in which a "very small man" named Niggle, works on a painting of a tree, but is so caught up with painstakingly painting individual leaves or elaborating the background, or so distracted by the demands of his neighbor, that he never manages to complete it.[48]

Tolkien never expected his fictional stories to become popular, but he was persuaded by C.S. Lewis to publish a book he had written for his own children called The Hobbit in 1937.[49] However, the book attracted adult readers as well, and it became popular enough for the publisher, George Allen & Unwin, to ask Tolkien to work on a sequel.

Even though he felt uninspired on the topic, this request prompted Tolkien to begin what would become his most famous work: the epic three-volume novel The Lord of the Rings (published 1954–1955). Tolkien spent more than ten years writing the primary narrative and appendices for The Lord of the Rings, during which time he received the constant support of the Inklings, in particular his closest friend Lewis, the author of The Chronicles of Narnia. Both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings are set against the background of The Silmarillion, but in a time long after it.

Tolkien at first intended The Lord of the Rings to be a children's tale in the style of The Hobbit, but it quickly grew darker and more serious in the writing.[50] Though a direct sequel to The Hobbit, it addressed an older audience, drawing on the immense back story of Beleriand that Tolkien had constructed in previous years, and which eventually saw posthumous publication in The Silmarillion and other volumes. Tolkien's influence weighs heavily on the fantasy genre that grew up after the success of The Lord of the Rings.

Tolkien continued to work on the history of Middle-earth until his death. His son Christopher Tolkien, with some assistance from fantasy writer Guy Gavriel Kay, organized some of this material into one volume, published as The Silmarillion in 1977. In 1980 Christopher Tolkien followed this with a collection of more fragmentary material under the title Unfinished Tales, and in subsequent years he published a massive amount of background material on the creation of Middle-earth in the twelve volumes of The History of Middle-earth. All these posthumous works contain unfinished, abandoned, alternative and outright contradictory accounts, since they were always a work in progress, and Tolkien only rarely settled on a definitive version for any of the stories. There is not even complete consistency to be found between The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit, the two most closely related works, because Tolkien was never able to fully integrate all their traditions into each other. He commented in 1965, while editing The Hobbit for a third edition, that he would have preferred to completely rewrite the entire book.[51]

The John P. Raynor, S.J., Library at Marquette University in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, preserves many of Tolkien's original manuscripts, notes and letters; other original material survives at Oxford's Bodleian Library. Marquette has the manuscripts and proofs of The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit, and other manuscripts, including Farmer Giles of Ham, while the Bodleian holds the Silmarillion papers and Tolkien's academic work.[52]

The Lord of the Rings became immensely popular in the 1960s and has remained so ever since, ranking as one of the most popular works of fiction of the twentieth century, judged by both sales and reader surveys.[53] In the 2003 "Big Read" survey conducted by the BBC, The Lord of the Rings was found to be the "Nation's Best-loved Book." Australians voted The Lord of the Rings "My Favourite Book" in a 2004 survey conducted by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation.[54] In a 1999 poll of Amazon.com customers, The Lord of the Rings was judged to be their favorite "book of the millennium".[55] In 2002 Tolkien was voted the 92nd "greatest Briton" (out of 100) in a poll conducted by the BBC, and in 2004 he was voted thirty-fifth in the SABC3's Great South Africans, the only person to appear in both lists. His popularity is not limited just to the English-speaking world: in a 2004 poll inspired by the UK’s "Big Read" survey, about 250,000 Germans found The Lord of the Rings (Der Herr der Ringe) to be their favorite work of literature.[56]

In September 2006, Christopher Tolkien, who had spent 30 years working on The Children of Húrin, announced that the book has been edited into a completed work for publication in 2007. J. R. R. Tolkien had been working on what he called the Húrin's saga (and later the Narn i Chîn Húrin) since 1918, but never developed a complete mature version. Extracts from the tale had been published before by Christopher Tolkien in The Silmarillion and his later literary investigations of The History of Middle-earth.

It has seemed to me for a long time that there was a good case for presenting my father's long version of the legend of The Children of Hurin as an independent work, between its own covers.[57]

Languages

Both Tolkien's academic career and his literary production are inseparable from his love of language and philology. He specialized in Ancient Greek philology in college, and in 1915 graduated with Old Icelandic as special subject. He worked for the Oxford English Dictionary from 1918, and is credited with having worked on a number of "W" words, including walrus, over which he struggled mightily.[58] In 1920, he went to Leeds as Reader in English Language, where he claimed credit for raising the number of students of linguistics from five to twenty. He gave courses in Old English heroic verse, history of English, various Old English and Middle English texts, Old and Middle English philology, introductory Germanic philology, Gothic, Old Icelandic, and Medieval Welsh. When in 1925, aged 33, Tolkien applied for the Rawlinson and Bosworth Professorship of Anglo-Saxon, he boasted that his students of Germanic philology in Leeds had even formed a "Viking Club".[59]

Privately, Tolkien was attracted to "things of racial and linguistic significance," and he entertained notions of an inherited taste of language, which he termed the "native tongue" as opposed to "cradle tongue" in his 1955 lecture "English and Welsh," which is crucial to his understanding of race and language. He considered west-midland Middle English his own "native tongue," and, as he wrote to W. H. Auden in 1955,[60] "I am a West-midlander by blood (and took to early west-midland Middle English as a known tongue as soon as I set eyes on it)"

Parallel to Tolkien's professional work as a philologist, and sometimes overshadowing this work, to the effect that his academic output remained rather thin, was his affection for the construction of artificial languages. The best developed of these are Quenya and Sindarin, the etymological connection between which formed the core of much of Tolkien's legendarium. Language and grammar for Tolkien was a matter of aesthetics and euphony, and Quenya in particular was designed from "phonaesthetic" considerations; it was intended as an "Elvenlatin," and was phonologically based on Latin, with ingredients from Finnish and Greek.[61] A notable addition came in late 1945 with Númenórean, a language of a "faintly Semitic flavour," connected with Tolkien's Atlantis legend, tied by The Notion Club Papers to his ideas about inheritability of language, and, via the "Second Age" and the story of Eärendil, grounded in the legendarium, providing a link of Tolkien's twentieth-century "real primary world" with the legendary past of his Middle-earth.

Tolkien considered languages inseparable from the mythology associated with them, and he consequently took a dim view of auxiliary languages: in 1930 a congress of Esperantists were told as much by him, in his lecture "A Secret Vice," "Your language construction will breed a mythology," but by 1956 he concluded that "Volapük, Esperanto, Ido, Novial, &c, &c, are dead, far deader than ancient unused languages, because their authors never invented any Esperanto legends".[62]

The popularity of Tolkien's books has had a small but lasting effect on the use of language in fantasy literature in particular, and even on mainstream dictionaries, which today commonly accept Tolkien's revival of the spellings dwarves and elvish (instead of dwarfs and elfish), which had not been in use since the mid-1800s and earlier. Other terms he has coined such as eucatastrophe are mainly used in connection with Tolkien's work.

Works inspired by Tolkien

In a 1951 letter to Milton Waldman, Tolkien writes about his intentions to create a "body of more or less connected legend", of which

The cycles should be linked to a majestic whole, and yet leave scope for other minds and hands, wielding paint and music and drama.[63]

The hands and minds of many artists have indeed been inspired by Tolkien's legends. Personally known to him were Pauline Baynes (Tolkien's favorite illustrator of The Adventures of Tom Bombadil and Farmer Giles of Ham) and Donald Swann (who set the music to The Road Goes Ever On). Queen Margrethe II of Denmark created illustrations to The Lord of the Rings in the early 1970s. She sent them to Tolkien, who was struck by the similarity they bore in style to his own drawings.[64]

But Tolkien was not fond of all the artistic representation of his works that were produced in his lifetime, and was sometimes harshly disapproving.

In 1946, he rejects suggestions for illustrations by Horus Engels for the German edition of the Hobbit as "too Disnified",

Bilbo with a dribbling nose, and Gandalf as a figure of vulgar fun rather than the Odinic wanderer that I think of.[65]

He was sceptical of the emerging Tolkien fandom in the United States, and in 1954 he returned proposals for the dust jackets of the American edition of The Lord of the Rings:

Thank you for sending me the projected 'blurbs', which I return. The Americans are not as a rule at all amenable to criticism or correction; but I think their effort is so poor that I feel constrained to make some effort to improve it.[66]

And in 1958, in an irritated reaction to a proposed movie adaptation of The Lord of the Rings by Morton Grady Zimmerman he writes,

I would ask them to make an effort of imagination sufficient to understand the irritation (and on occasion the resentment) of an author, who finds, increasingly as he proceeds, his work treated as it would seem carelessly in general, in places recklessly, and with no evident signs of any appreciation of what it is all about.[67]

He went on to criticize the script scene by scene ("yet one more scene of screams and rather meaningless slashings"). But Tolkien was, in principle, open to the idea of a movie adaptation. He sold the film, stage and merchandise rights of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings to United Artists in 1968, while, guided by scepticism towards future productions, he forbade that Disney should ever be involved:

It might be advisable […] to let the Americans do what seems good to them—as long as it was possible […] to veto anything from or influenced by the Disney studios (for all whose works I have a heartfelt loathing).[68]

In 1976 the rights were sold to Tolkien Enterprises, a division of the Saul Zaentz Company, and the first movie adaptation (an animated rotoscoping film) of The Lord of the Rings appeared only after Tolkien's death (in 1978), directed by Ralph Bakshi). The screenplay was written by the fantasy writer Peter S. Beagle. This first adaptation contained the first half of the story that is The Lord of the Rings. In 1977 an animated television production of The Hobbit was made by Rankin-Bass, and in 1980 they produced an animated film titled The Return of the King, which covered some of the portion of The Lord of the Rings that Bakshi was unable to complete. In 2001, New Line Cinema released The Lord of the Rings as a trilogy of live-action films, directed by Peter Jackson.

Bibliography

Fiction and poetry

- 1936 Songs for the Philologists, with E.V. Gordon et al.

- 1937 The Hobbit or There and Back Again, ISBN 0-618-00221-9 (Houghton Mifflin).

- 1945 Leaf by Niggle (short story)

- 1945 The Lay of Aotrou and Itroun, published in Welsh Review

- 1949 Farmer Giles of Ham (medieval fable)

- 1953 The Homecoming of Beorhtnoth Beorhthelm's Son (a play written in alliterative verse), published with the accompanying essays Beorhtnoth's Death and Ofermod, in Essays and Studies by members of the English Association, volume 6.

- The Lord of the Rings

- 1954 The Fellowship of the Ring: being the first part of The Lord of the Rings, ISBN 0-618-00222-7 (HM).

- 1954 The Two Towers: being the second part of The Lord of the Rings, ISBN 0-618-00223-5 (HM).

- 1955 The Return of the King: being the third part of The Lord of the Rings, ISBN 0-618-00224-3 (HM).

- 1962 The Adventures of Tom Bombadil and Other Verses from the Red Book

- 1967 The Road Goes Ever On, with Donald Swann

- 1964 Tree and Leaf (On Fairy-Stories and Leaf by Niggle in book form)

- 1966 The Tolkien Reader (The Homecoming of Beorhtnoth Beorhthelm's Son, On Fairy-Stories, Leaf by Niggle, Farmer Giles of Ham' and The Adventures of Tom Bombadil)

- 1967 Smith of Wootton Major

Academic and other works

- 1922 A Middle English Vocabulary, Oxford, Clarendon Press.

- 1925 Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, co-edited with E.V. Gordon, Oxford University Press; Revised ed. 1967, Oxford, Clarendon Press.

- 1925 "Some Contributions to Middle-English Lexicography," in The Review of English Studies, volume 1, no. 2, 210-215.

- 1925 "The Devil's Coach Horses," in The Review of English Studies, volume 1, no. 3, 331-336.

- 1929 "Ancrene Wisse and Hali Meiðhad," in Essays and Studies by members of the English Association, Oxford, volume 14, 104-126.

- 1932 "The Name 'Nodens'," in Report on the Excavation of the Prehistoric, Roman, and Post-Roman Site in Lydney Park, Gloucestershire, Oxford, University Press for The Society of Antiquaries.

- 1932–1934 "Sigelwara Land." parts I and II, in Medium Aevum. Oxford, volume 1, no. 3 (December 1932), 183-196 and volume 3, no. 2 (June 1934), 95-111.

- 1934 "Chaucer as a Philologist: The Reeve's Prologue and Tale," in Transactions of the Philological Society. London, 1-70 (rediscovery of dialect humor, introducing the Hengwrt manuscript into textual criticism of Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales)

- 1937 Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics. London: Humphrey Milford, (publication of his 1936 lecture on Beowulf criticism)

- 1939 "The Reeve's Tale: version prepared for recitation at the 'summer diversions," Oxford.

- 1939 "On Fairy-Stories" (1939 Andrew Lang lecture) - concerning Tolkien's philosophy on fantasy, this lecture was a shortened version of an essay later published in full in 1947.

- 1944 "Sir Orfeo,: Oxford: The Academic Copying Office, (an edition of the medieval poem)

- 1947 "On Fairy-Stories" (essay - published in Essays presented to Charles Williams. Oxford University Press) - first full publication of an essay concerning Tolkien's philosophy on fantasy, and which had been presented in shortened form as the 1939 Andrew Lang lecture.

- 1953 "Ofermod" and "Beorhtnoth's Death," two essays published with the poem "The Homecoming of Beorhtnoth, Beorhthelm's Son" in Essays and Studies by members of the English Association, volume 6.

- 1953 "Middle English "Losenger": Sketch of an etymological and semantic enquiry," in Essais de philologie moderne: Communications présentées au Congrès International de Philologie Moderne. (1951), Les Belles Lettres.

- 1962 Ancrene Wisse: The English Text of the Ancrene Riwle. Early English Text Society, Oxford University Press.

- 1963 English and Welsh, in Angles and Britons: O'Donnell Lectures, University of Cardiff Press.

- 1964 Introduction to Tree and Leaf, with details of the composition and history of Leaf by Niggle and On Fairy-Stories.

- 1966 Contributions to the Jerusalem Bible (as translator and lexicographer)

- 1966 Foreword to the Second Edition of The Lord of the Rings, with Tolkien's comments on the varied reaction to his work, his motivation for writing the work, and his opinion of allegory.

- 1966 Tolkien on Tolkien (autobiographical)

Posthumous publications

- 1975 "Guide to the Names in The Lord of the Rings," (edited version) - published in A Tolkien Compass by Jared Lobdell. Written by Tolkien for use by translators of The Lord of the Rings. A full version was published in 2004 in The Lord of the Rings: A Reader's Companion by Wayne Hammond and Christina Scull.

- 1975 Translations of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Pearl (poem) and Sir Orfeo

- 1976 The Father Christmas Letters (children's stories), reprinted 2004 ISBN 0618512659.

- 1977 The Silmarillion ISBN 0618126988.

- 1979 Pictures by J. R. R. Tolkien

- 1980 Unfinished Tales of Númenor and Middle-earth ISBN 0618154051.

- 1980 Poems and Stories (a compilation of The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, The Homecoming of Beorhtnoth Beorhthelm's Son, On Fairy-Stories, Leaf by Niggle, Farmer Giles of Ham, and Smith of Wootton Major)

- 1981 The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, (eds. Christopher Tolkien and Humphrey Carpenter)

- 1981 The Old English Exodus Text

- 1982 Finn and Hengest: The Fragment and the Episode

- 1982 Mr. Bliss

- 1983 The Monsters and the Critics (an essay collection)

- Beowulf: the Monsters and the Critics (1936)

- On Translating Beowulf (1940)

- On Fairy-Stories (1947)

- A Secret Vice (1930)

- English and Welsh (1955)

- 1983–1996 The History of Middle-earth:

- The Book of Lost Tales 1 (1983)

- The Book of Lost Tales 2 (1984)

- The Lays of Beleriand (1985)

- The Shaping of Middle-earth (1986)

- The Lost Road and Other Writings (1987)

- The Return of the Shadow (The History of The Lord of the Rings vol. 1) (1988)

- The Treason of Isengard (The History of The Lord of the Rings vol. 2) (1989)

- The War of the Ring (The History of The Lord of the Rings vol. 3) (1990)

- Sauron Defeated (The History of The Lord of the Rings vol. 4, including The Notion Club Papers) (1992)

- Morgoth's Ring (The Later Silmarillion vol. 1) (1993)

- The War of the Jewels (The Later Silmarillion vol. 2) (1994)

- The Peoples of Middle-earth (1996)

- Index (2002)

- 1995 J.R.R. Tolkien: Artist and Illustrator (a compilation of Tolkien's art)

- 1998 Roverandom

- 2001 Unfinished Tales of Numenor and Middle-Earth co-authored by Christopher Tolkien ISBN 0618154043

- 2002 A Tolkien Miscellany - a collection of previously published material

- 2002 Beowulf and the Critics, ed. Michael D.C. Drout (Beowulf: the monsters and the critics together with editions of two drafts of the longer essay from which it was condensed.)

- 2004 Guide to the Names in The Lord of the Rings (full version) - published in The Lord of the Rings: A Reader's Companion by Wayne Hammond and Christina Scull. Written by Tolkien for use by translators of The Lord of the Rings.

- 2007 The Children of Húrin ISBN 0547086059

Audio recordings

- 1967 Poems and Songs of Middle-earth, Caedmon TC 1231

- 1975 JRR Tolkien Reads and Sings his The Hobbit & The Lord of the Rings, Caedmon TC 1477, TC 1478 (based on an August, 1952 recording by George Sayer)

Notes

- ↑ Humphrey Carpenter, and Christopher Tolkien, eds. The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien. (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1981), no. 165

- ↑ undergraduate John Jethro Rashbold, and Old Professor Rashbold at Pembroke; Carpenter and Tolkien, Letter no. 165

- ↑ Humphrey Carpenter. Tolkien: A Biography. (New York: Ballantine Books, 1977. ISBN 0049280376), 22

- ↑ Carpenter, 1977, 21

- ↑ Carpenter, 1977, 24

- ↑ Carpenter, 1977, 27

- ↑ Carpenter, 1977, 113

- ↑ Carpenter, 1977, 29

- ↑ David Doughan. 2002 JRR Tolkien Biography Life of Tolkien accessdate 2006-03-12

- ↑ Carpenter, 1977, 22

- ↑ Carpenter and Tolkien, Letters, no. 306

- ↑ Carpenter, 1977, 39

- ↑ Humphrey Carpenter. The Inklings. (Allen & Unwin, 1978.) Lewis was brought up in the Church of Ireland, and as an adult joined the Church of England.

- ↑ Doughan, J. R. R. Tolkien: A Biographical Sketch. 2002, #2 War, Lost Tales And Academia. thetolkiensociety. accessdate 2006-03-12

- ↑ Carpenter, 1977, 53 – 54

- ↑ Carpenter and Tolkien, Letters, no. 306

- ↑ Carpenter, 1977, 67 – 69

- ↑ Carpenter, 1977, 73

- ↑ Carpenter, 1977, 85

- ↑ Carpenter, 1977, 93

- ↑ Following rural English usage, Tolkien used the name 'hemlock' for various plants with white flowers in umbels, resembling the poison hemlock; the flowers among which Edith danced were more probably cow parsley (Anthriscus sylvestris) or Queen Anne's lace (Daucus carota). See John Garth. Tolkien and the Great War. (HarperCollins/Houghton Mifflin, 2003) and Peter Gilliver, Jeremy Marshall, & Edmund Weiner. The Ring of Words. (Oxford Univ. Press, 2006).

- ↑ Bill Cater, April 12, 2001, We talked of love, death, and fairy tales. UK Telegraph accessdate 2006-03-13

- ↑ Peter Gilliver, Jeremy Marshall and Edmund Weiner. The Ring of Words: Tolkien and the OED. (Oxford University Press, 2006)

- ↑ See The Name Nodens (1932)

- ↑ Carpenter, 1977, 143

- ↑ Bill Ramey, March 30, 1998, The Unity of Beowulf: Tolkien and the Critics Wisdom's Children accessdate 2006-03-13

- ↑ Michael Kennedy, 2001, Tolkien and Beowulf- Warriors of Middle-earth Amon Hen accessdate 2006-05-18

- ↑ J.R.R. Tolkien. Finn and Hengest. "Introduction" by Alan Bliss 4 ; for the parenthesis, the discussion of Eotena, passim.

- ↑ Carpenter and Tolkien, Letters, no. 327

- ↑ Doughan, 2002, JRR Tolkien Biography Life of Tolkien accessdate 2006-03-13

- ↑ Phyllis Meras, January 15, 1967, Go, Go, Gandalf New York Times accessdate 2006-03-12

- ↑ Calendar and Tolkien, Letters, no. 336. Chu-Bu and Sheemish are idols in a 1912 story by Edward Plunkett, 18th Baron Dunsany)

- ↑ People of Stoke-on-Trent, [1] thepotteries.org. accessdate 2005-03-13

- ↑ Carpenter, 1977; Carpenter and Tolkien, Letters

- ↑ Carpenter, 1977

- ↑ Was Tolkien a Racist?.tolkien.slimy.com. Retrieved October 23, 2008.

- ↑ when asked to declare he was Aryan by German Nazi publishers, he declined to answer, instead stating: "… I regret that I appear to have no ancestors of that gifted [Jewish] people." He gave his publishers a choice of two letters to send in reply; these quotations are from the less tactful one, which was not sent. Carpenter and Tolkien, Letters, no. 29, 30.

- ↑ "I have the hatred of apartheid in my bones; and most of all I detest the segregation or separation of Language and Literature. I do not care which of them you think White." —published in The Monsters and the Critics. (1983). ISBN 0048090190

- ↑ Carpenter and Tolkien, Letters

- ↑ Carpenter and Tolkien, Letters, 63-64

- ↑ Wayne G. Hammond. J.R.R. Tolkien: A Descriptive Bibliography. (London: Saint Pauls Biographies, 1993)

- ↑ David Day. (Canadian) Tolkien's Ring. (New York: Barnes and Noble, 2002. ISBN 1586635271)

- ↑ As described by Christopher Tolkien in Hervarar Saga ok Heidreks Konung (Oxford University, Trinity College). B. Litt. thesis. 1953/1954. The Battle of the Goths and the Huns, in: Saga-Book. (University College, London, for the Viking Society for Northern Research) 14, part 3 (1955-1956) [2]

- ↑ Brian Handwerk, March 1, 2004, Lord of the Rings Inspired by an Ancient Epic. National Geographic News. accessdate 2006-03-13

- ↑ John Gardner. October 23, 1977, The World of Tolkien New York Times

- ↑ Jason Bofetti, November 2001, "Tolkien's Catholic Imagination" Crisis Magazine.

- ↑ Norman Phillip, 2005, The Prevalance of Hobbits. New York Times accessdate 2006-03-12}

- ↑ Leaf by Niggle - a symbolic story about a small painter. Tolkien Library, 2005, accessdate 2006-03-12

- ↑ Times Editorial Staff, September 3, 1973, J.R.R. Tolkien Dead at 81: Wrote "The Lord of the Rings" New York Times accessdate 2006-03-12

- ↑ Times Editorial Staff, June 5, 1955, Oxford Calling New York Times accessdate 2006-03-12

- ↑ Michael Martinez, December 7, 2004, Middle Earth Roleplaying Middle-earth Revised, Again Merp.com.

- ↑ Edwin McDowell, September 4, 1983, Middle-earth Revisited. New York Times accessdate 2006-03-12

- ↑ Andy Seiler, December 16, 2003, 'Rings' comes full circle USA Today accessdate 2006-03-12

- ↑ Callista Cooper, December 5, 2005, Epic trilogy tops favorite film poll. ABC News Online. accessdate 2006-03-12

- ↑ Andrew O'Hehir, June 4, 2001, The book of the century. Salon.com. accessdate 2006-03-12

- ↑ Krysia Diver, October 5, 2004, A lord for Germany The Sydney Morning Herald. accessdate 2006-03-12

- ↑ Christopher Tolkien, Sept. 19, 2006, Son completes unfinished Tolkien.BBC News. Retrieved October 23, 2008.

- ↑ Simon Winchester. The Meaning of Everything: The Story of the Oxford English Dictionary. (Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 0965499634)

- ↑ Carpenter and Tolkien, 1991, Letters, no 7, (Letter dated June 27, 1925 to the Electors of the Rawlinson and Bosworth Professorship of Anglo-Saxon, University of Oxford.

- ↑ Carpenter and Tolkien, Letters, no. 163

- ↑ Carpenter and Tolkien, Letters, no. 144, (April 25, 1954, to Naomi Mitchison)

- ↑ Carpenter and Tolkien, Letters, no. 180

- ↑ Carpenter and Tolkien, Letters, no. 131

- ↑ Peter Thygesen, (Autumn, 1999) Queen Margrethe II: Denmark's monarch for a modern age. Scandinavian Review accessdate 2006-03-12

- ↑ Carpenter and Tolkien, Letters, no. 107

- ↑ Carpenter and Tolkien, Letters, no. 144

- ↑ Carpenter and Tolkien, Letters, no. 207

- ↑ Carpenter and Tolkien, Letters, no. 13

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Anderson, Douglas A., Michael D. C. Drout and Verlyn Flieger, eds. Tolkien Studies, An Annual Scholarly Review. Vol. I. West Virginia University Press, 2004. ISBN 0937058874.

- Birzer, Bradley. J.R.R. Tolkien's Sanctifying Myth: Understanding Middle-earth. ISI Books.

- Bruner, Kurt D. and Jim Ware. Finding God in the Lord of the Rings. 2003. ISBN 084238555X.

- Carpenter Humphrey. Tolkien: A Biography. New York: Ballantine Books, 1977. ISBN 0049280376 (biography)

- Carpenter, Humphrey. The Inklings: C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, Charles Williams and Their Friends. 1979. ISBN 0395276284.

- Carpenter, Humphrey and Christopher Tolkien, eds. The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien. London: George Allen & Unwin, 1981. ISBN 0048260053.

- Chance, Jane, ed. Tolkien the Medievalist. London; New York: Routledge, 2003. ISBN 0415289440

- Chance, Jane. Tolkien and the Invention of Myth, a Reader. Louisville: University Press of Kentucky, 2004. ISBN 0813123011.

- Curry, Patrick. Defending Middle-earth: Tolkien, Myth and Modernity. 2004. ISBN 061847885X.

- Day, David. (Canadian) Tolkien's Ring. New York: Barnes and Noble, 2002. ISBN 1586635271.

- Duriez, Colin. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis: The Gift of Friendship. 2003. ISBN 1587680262.

- Duriez, Colin and David Porter. The Inklings Handbook: The Lives, Thought and Writings of C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien, Charles Williams, Owen Barfield, and Their Friends. 2001. ISBN 1902694139.

- Flieger, Verlyn and Carl F. Hostetter. Tolkien's Legendarium: Essays on The History of Middle-earth. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2000. ISBN 0313305307.

- Gilliver, Peter and Jeremy Marshall, Edmund Weiner. The Ring of Words: Tolkien and the Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 2006. ISBN 0198610696.

- Haber, Karen. Meditations on Middle-earth: New Writing on the Worlds of J. R. R. Tolkien. St. Martin's Press. 2001. ISBN 0312275366.

- Hammond, Wayne G. and Douglas A. Anderson. J.R.R. Tolkien: A Descriptive Bibliography. London: Saint Pauls Biographies, 1993. ISBN 0938768425.

- Harrington, Patrick. Tolkien and Politics. London: Third Way Publications Ltd., 2003. ISBN 0954478827.

- Lee, S. D., and E. Solopova, ed. The Keys of Middle-earth: Discovering Medieval Literature through the Fiction of J. R. R. Tolkien. Palgrave Macmillan, 2005. ISBN 140394671X.

- O'Neill, Timothy R. The Individuated Hobbit: Jung, Tolkien and the Archetypes of Middle-earth. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1979. ISBN 039528208X

- Pearce, Joseph. Tolkien: Man and Myth. London: HarperCollinsPublishers, 1998. ISBN 0002740184

- Shippey, T. A. J. R. R. Tolkien—Author of the Century. Boston; New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2000. ISBN 0618257594.

- Strachey, Barbara. Journeys of Frodo: an Atlas of The Lord of the Rings.Boston: Allen & Unwin, 1981. ISBN 0049120166.

- Tolkien, John & Priscilla. The Tolkien Family Album. London: HarperCollins, 1992. ISBN 0261102397

- White, Michael. Tolkien: A Biography. New American Library, 2003. ISBN 0451212428.

External links

All links retrieved December 13, 2024.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.