Toy

A toy or plaything is an object that is used primarily to provide entertainment. Simple examples include toy blocks, board games, and dolls. Utilitarian objects, especially those which are no longer needed for their original purpose, can also be used as toys. The term "toy" can also be used to refer to utilitarian objects purchased for enjoyment rather than need, or for expensive necessities for which a large fraction of the cost represents its ability to provide enjoyment to the owner, such as luxury cars, high-end motorcycles, gaming computers, and flagship smartphones.

Different materials like wood, clay, paper, and plastic are used to make toys. Newer forms of toys include interactive digital entertainment and smart toys. Some toys are produced primarily as collectors' items and are intended for display only.

Playing with toys can be an enjoyable way of training young children for life experiences and is an important part of development. Younger children use toys to discover their identity, help with cognition, learn cause and effect, explore relationships, become stronger physically, and practice skills needed in adulthood. Adults on occasion use toys to form and strengthen social bonds, teach, help in therapy, and to remember and reinforce lessons from their youth.

History

Toys have existed since early times; dolls representing infants, animals, and soldiers, as well as representations of tools used by adults, have been found at many archaeological sites. The oldest known doll toy is a 4,000-year-old stone doll head found in the ruins of a village on the Italian island of Pantelleria.[1]

The origin of the word "toy" is unknown, but it is believed that it was first used in the fourteenth century to mean "amorous playing, sport," and later "piece of fun or entertainment." [2]

Antiquity

Toys and games have been retrieved from the sites of ancient civilizations, and have been mentioned in ancient literature. The earliest toys were made from natural materials, such as rocks, sticks, and clay. For example, items excavated from the Indus valley civilization include small carts, whistles shaped like birds, and toy monkeys that could slide down a string.[3]

Egyptian children played with dolls that had wigs and movable limbs, which were made from stone, pottery, and wood.[4] However, evidence of toys in ancient Egypt is difficult to identify with certainty. Small figurines and models found in tombs are usually interpreted as ritual objects; those from settlement sites are more easily labelled as toys. These include spinning tops, balls of spring, and wooden models of animals with movable parts.[5]

In ancient Greece and ancient Rome, children played with dolls made of wax or terracotta: sticks, bows and arrows, and yo-yos. When Greek children, especially girls, came of age, it was customary for them to sacrifice the toys of their childhood to the gods. On the eve of their wedding, young girls around fourteen would offer their dolls in a temple as a rite of passage into adulthood.[6]

The oldest known mechanical puzzle, which appeared in the third century B.C.E., also comes from ancient Greece. The toy consisted of a square divided into 14 parts, and the aim was to create different shapes from the pieces. One form of play to which classical texts attest is the creation of different objects, animals, or plants by rearranging the pieces: an elephant, a tree, a barking dog, a ship, a sword, a tower and so forth. Another suggestion is that it exercised and developed memory skills in the young, by putting the pieces back in their box in a specific arrangement.[7]

Enlightenment Era

Toys became more widespread with changing Western attitudes towards children and childhood brought about by the Enlightenment. Previously, children had often been thought of as small adults, who were expected to work in order to produce the goods that the family needed to survive. As children's culture scholar Stephen Kline has argued, Medieval children were:

more fully integrated into the daily flux of making and consuming, of getting along. They had no autonomy, separate statuses, privileges, special rights or forms of social comportment that were entirely their own.[8]

As these ideas began changing during the Enlightenment Era, blowing bubbles from leftover washing up soap became a popular pastime, as shown in the painting The Soap Bubble (1739) by Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, and other popular toys included hoops, toy wagons, kites, spinning wheels and puppets. Many board games were produced by John Jefferys in the 1750s, including A Journey Through Europe.[9] The game was very similar to modern board games; players moved along a track with the throw of a die (a teetotum was actually used) and landing on different spaces would either help or hinder the player.

The first jigsaw puzzle was produced around 1760 by John Spilsbury, a London cartographer and engraver. His design took world maps, and cut out the individual nations in order for them to be reassembled by students as a geographical teaching aid. His early puzzles, known as "dissected maps," were produced by mounting maps on sheets of hardwood and cutting along national boundaries. The name "jigsaw" came to be associated with the puzzle around 1880 when the jig saw was invented and made it possible to cut more intricate shapes. It also reduced the time to cut the pieces, with the result that they were cheaper and so became more popular.[10]

In the nineteenth century, Western values prioritized toys with an educational purpose, such as puzzles, books, cards and board games. Religion-themed toys were also popular, including a model Noah's Ark with miniature animals and objects from other Bible scenes. With growing prosperity among the middle class, children had more leisure time on their hands, which led to the application of industrial methods to the manufacture of toys.

More complex mechanical and optical-based toys were also invented during the nineteenth century. Carpenter and Westley began to mass-produce the kaleidoscope, invented by Sir David Brewster in 1817, and had sold over 200,000 items within three months in London and Paris. The modern zoetrope was invented in 1833 by British mathematician William George Horner and was popularized in the 1860s.[11]

Industrial Era

The golden age of toy development occurred during the Industrial Era. Real wages were rising steadily in the Western world, allowing even working-class families to afford toys for their children, and industrial techniques of precision engineering and mass production were able to provide the supply to meet this rising demand. Intellectual emphasis was also increasingly being placed on the importance of a wholesome and happy childhood for the future development of children.

Franz Kolb, a German pharmacist, invented plasticine in 1880, and in 1900 commercial production of the material as a children's toy began. Frank Hornby was a visionary in toy development and manufacture and was responsible for the invention and production of three of the most popular lines of toys based on engineering principles in the twentieth century: Meccano, Hornby Model Railways, and Dinky Toys. Meccano was a model construction system that consisted of re-usable metal strips, plates, angle girders, wheels, axles and gears, with nuts and bolts to connect the pieces and enabled the building of working models and mechanical devices. Dinky Toys pioneered the manufacture of die-cast toys with the production of toy cars, trains and ships and model train sets became popular in the 1920s. The Britain's company revolutionized the production of toy soldiers with the invention of the process of hollow casting in lead in 1893.[12]

Puzzles became popular as well. In 1893, the English lawyer Angelo John Lewis, writing under the pseudonym of Professor Hoffmann, wrote a book called Puzzles Old and New.[13] It contained, among other things, more than 40 descriptions of puzzles with secret opening mechanisms. This book grew into a reference work for puzzle games and was very popular at the time.

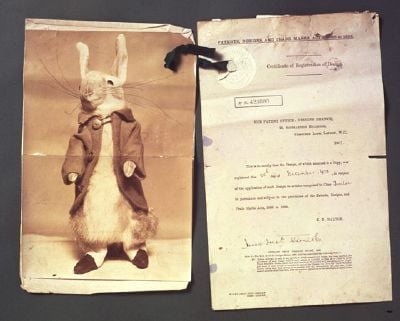

In 1903, a year after publishing The Tale of Peter Rabbit, English author Beatrix Potter created the first Peter Rabbit soft toy and registered him at the Patent Office in London, making Peter the oldest licensed character.[14] It was followed by other "spin-off" merchandise over the years, including painting books and board games. The merchandising of literary characters has developed into a major industry:

Potter was also an entrepreneur and a pioneer in licensing and merchandising literary characters. Potter built a retail empire out of her “bunny book” that is worth $500 million today. In the process, she created a system that continues to benefit all licensed characters, from Mickey Mouse to Harry Potter.[15]

The beginning of the twentieth century also saw the arrival of the "Teddy bear," named for President Theodore Roosevelt. The name originated from an incident on a bear hunting trip in Mississippi in November 1902, to which Roosevelt was invited by Mississippi Governor Andrew H. Longino. There were several other hunters competing, and most of them had already killed an animal. Roosevelt's attendants cornered, clubbed, and tied an American black bear to a willow tree after a long exhausting chase with hounds. They called Roosevelt to the site and suggested that he shoot it. He refused to shoot the bear himself, deeming this unsportsmanlike, and it became the topic of a political cartoon by Clifford Berryman in The Washington Post on November 16, 1902.

Morris Michtom saw the Berryman drawing of Roosevelt and he and his wife were inspired to create a toy bear, the first "Teddy bear," and the rest is history:

That night, Rose cut and stuffed a piece of plush velvet into the shape of a bear, sewed on shoe button eyes and handed it to Morris to display in the shop window. He labeled it, "Teddy’s bear." To his surprise, not only did someone enter the store asking to buy the bear, but twelve other potential customers also asked to purchase it. Aware that he might offend the president by using his name without permission, the Michtoms mailed the original bear to the White House, offering it as a gift to the president’s children and asking Roosevelt for the use of his name. He told the Michtoms he doubted his name would help its sales but they were free to use it if they wanted.[16]

In tandem with the development of mass-produced toys, Enlightenment ideals about children's rights to education and leisure time came to fruition. During the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, many families needed to send their children to work in factories and other sites to make ends meet—just as their predecessors had required their labor producing household goods in the medieval era.[17] By the twentieth century, however, child labor laws were passed, thus fully entrenching the idea that childhood is a time for leisure, not work. With children's free time came demand for more toys.[18]

During the Second World War, some new types of toys were created through accidental innovation. After trying to create a replacement for synthetic rubber, the American Earl L. Warrick inadvertently invented "nutty putty" during World War II. Later, Peter Hodgson recognized the potential as a childhood plaything and packaged it as Silly Putty. [19] In 1943 Richard James was experimenting with springs as part of his military research when he saw one come loose and fall to the floor. He was intrigued by the way it flopped around on the floor. He spent two years fine-tuning the design to find the best gauge of steel and coil; the result was the Slinky, which went on to sell in stores throughout the United States.[20]

After the Second World War, as society became ever more affluent and new technology and materials (plastics) for toy manufacture became available, toys became cheap and ubiquitous in households across the Western World. At this point, name-brand toys became widespread in the U.S.–a new phenomenon that helped market mass-produce toys to audiences of children growing up with ample leisure time and during a period of relative prosperity.[18]

Types

Toys are generally designed for use by children, although some may be designed for adults or pets. Beyond those items specifically designed as playthings, utilitarian objects, especially those which are no longer needed for their original purpose, can also used as toys. For example, children may build a fort with empty boxes. The term "toy" can also be used to refer to utilitarian objects purchased for enjoyment rather than need, or for expensive necessities for which a large fraction of the cost represents its ability to provide enjoyment to the owner, such as luxury cars, high-end motorcycles, gaming computers, and flagship smartphones.

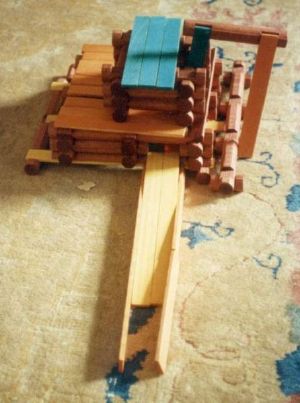

Construction sets

A construction set is a collection of separate pieces that can be joined to create models. Popular models include cars, spaceships, and houses. The items constructed are sometimes used as toys once completed, but generally speaking, it is the act of building that is valued. The purpose is to build items of one's own design, and old models often are broken up so that the pieces can be reused in new models. Construction sets appeal to children (and adults) who like to work with their hands, puzzle solvers, and those with creative minds.

The oldest and perhaps most common construction toy is a set of simple wooden blocks, which are often painted in bright colors and given to babies and toddlers. Construction sets such as Lego bricks and Lincoln Logs are designed for slightly older children.

Dolls and miniatures

A doll is a model of a human (often a baby), a humanoid (like Bert and Ernie), or an animal. Modern dolls are often made of cloth or plastic. Other materials that are, or have been, used in the manufacture of dolls include cornhusks, bone, stone, wood, porcelain (sometimes called china), bisque, celluloid, and wax. Often, people will make dolls out of whatever materials are available to them.

Sometimes intended as decorations, keepsakes, or collectibles for older children and adults, most dolls are intended as toys for children, usually girls, to play with. Dolls have been found in Egyptian tombs that date to as early as 2000 B.C.E.[4]

Dolls are usually miniatures, but baby dolls may be of true size and weight. A doll or stuffed animal of soft material is sometimes called a plush toy or plushie. A popular toy of this type is the Teddy bear.

A distinction is often made between dolls and action figures, which are generally of plastic or semi-metallic construction and poseable to some extent, and often are merchandising from television shows or films which feature the characters.

Toy soldiers, perhaps a precursor to modern action figures, have been a popular toy for centuries. They allow children (and adults) to act out battles, often with toy military equipment and a castle or fort. Miniature animal figures are also widespread, allowing for acting out farm activities with animals and equipment on a toy farm.

Puzzles

A puzzle is a problem or enigma that challenges ingenuity. Solutions to puzzles may require recognizing patterns and creating a particular order. People with a high inductive reasoning aptitude may be better at solving these puzzles than others. Puzzles based on the process of inquiry and discovery to complete may be solved faster by those with good deduction skills.

There are many different types of puzzles; for example, a maze is a type of tour puzzle. Other categories include: construction puzzles, stick puzzles, tiling puzzles, disentanglement puzzles, sliding puzzles, logic puzzles, picture puzzles, lock puzzles, and mechanical puzzles. A popular puzzle toy is the Rubik's Cube, invented by Hungarian Ernő Rubik in 1974. Popularized in the 1980s, solving the cube requires planning and problem-solving skills and involves algorithms.

Vehicles

Children have played with miniature versions of vehicles since ancient times, with toy two-wheeled carts being depicted on ancient Greek vases. Wind-up toys have also played a part in the advancement of toy vehicles. Modern equivalents include toy cars such as those produced by Matchbox or Hot Wheels, miniature aircraft, toy boats, military vehicles, and trains. Examples of the latter range from wooden sets, such as BRIO, for younger children, to more complicated realistic train models like those produced by Lionel, Doepke, and Hornby.

Physical activity

Many toys are part of active play. These include traditional toys such as hoops, tops, jump ropes, and balls, as well as more modern toys like Frisbees, foot bags, fidget toys, astrojax, and Myachi.

Playing with these sorts of toys allows children to exercise, building strong bones and muscles and aiding in physical fitness. Throwing and catching balls and Frisbees can improve hand–eye coordination. Jumping rope, (also known as skipping) and playing with foot bags can improve balance.

Promotional merchandise

Many successful films, television programs, books, and sport teams have official merchandise, which often includes related toys. Some notable examples are Star Wars (a space fantasy franchise) and Arsenal, an English football club.

Likewise, many successful children's films, television series, books or franchises extend their marketing campaign to fast food chains by including small toys of fictional characters or the series' associated symbols in a sealed plastic bag within their kids' meals.

Promotional toys can fall into any of the other toy categories; for example, they can be dolls or action figures based on the characters of movies or professional athletes, or they can be balls, yo-yos, or lunch boxes with logos on them. Sometimes they are given away for free as a form of advertising. Model aircraft are often toys that are used by airlines to promote their brand, just as toy cars and trucks and model trains are used by trucking, railroad, and other companies. Many food manufacturers run promotions where a toy is included with the main product as a prize. Toys are also used as premiums, where consumers redeem proofs of purchase from a product and pay shipping and handling fees to get the toy.

Digital toys

Digital toys are toys that incorporate some form of interactive digital technology. Examples include virtual pets and handheld electronic games. Among the earliest digital toys are Mattel Auto Race and the Little Professor, both released in 1976.

Collectibles

Some toys, such as Beanie Babies, attract large numbers of enthusiasts, eventually becoming collectibles. Other toys, such as Boyds Bears are marketed to adults as collectibles. Some people spend large sums of money in an effort to acquire larger and more complete collections.

Child development

Toys, like play itself, serve multiple purposes in both humans and animals. They provide entertainment while fulfilling an educational role. Toys enhance cognitive behavior and stimulate creativity. They aid in the development of physical and mental skills which are necessary in later life.

Wooden blocks, though simple, are regarded by early childhood education experts as an excellent toy for young children. They are relatively easy to engage with, can be used in repeatable and predictable ways, and are versatile and open-ended, allowing for a wide variety of developmentally appropriate play.[21] They also help develop hand-eye coordination, as well as math and science skills, while encouraging creativity.[22] Other toys like marbles, jackstones, and balls serve similar functions in child development, allowing children to use their minds and bodies to learn about spatial relationships, cause and effect, and a wide range of other skills.

One example of the dramatic ways that toys can influence child development is clay sculpting toys, such as Play-Doh and Silly Putty and their home-made counterparts. Such toys have been shown to positively impact children's physical development, cognitive development, emotional development, and social development.[23]

Toys for infants often make use of distinctive sounds, bright colors, and unique textures. Through repetition of play with toys, infants begin to recognize shapes and colors.

Educational toys for school age children of often contain a puzzle, problem-solving technique, or mathematical proposition. Often toys designed for older audiences, such as teenagers or adults, demonstrate advanced concepts. Newton's cradle, a desk toy designed by Simon Prebble, demonstrates the conservation of momentum and energy.

There is a modern trend of children moving through play stages faster than was the case in the past, whereby children progress to more complex toys at a faster pace, girls in particular. Barbie dolls, for example, were once marketed to girls around 8 years old but have been found to be more popular in recent years with girls around 3 to 7 years old.[24] The packaging for the dolls labels them as appropriate for ages 3 and up.

Boys, by contrast, apparently enjoy toys and games over a longer timespan, gravitating towards toys that meet their interest in assembling and disassembling mechanical toys, and toys that "move fast and things that fight." Girls mature earlier, entering the "tween" phase by the time they are 8 years old and want non-traditional toys, whereas boys maintain an interest in traditional toys until they are 12 years old, meaning the traditional toy industry holds onto their boy customers for 50 percent longer than their girl customers.[24]

Culture

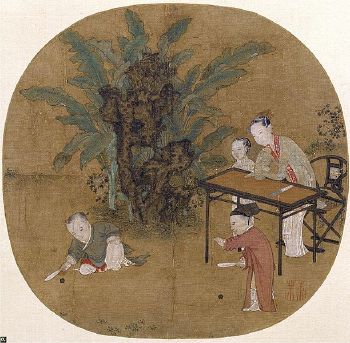

The act of children's play with toys embodies the values set forth by the adults of their specific community, but through the lens of the child's perspective. Within cultural societies, toys are a medium to enhance a child's cognitive, social, and linguistic learning.[25]

In some cultures, toys are used as a way to enhance a child's skillset within the traditional boundaries of their future roles in the community. In Saharan and North African cultures, play is facilitated by children through the use of toys to enact scenes recognizable in their community, such as hunting and herding. This allows the child to imagine and create a personal interpretation of how they view the adult world.[26]

However, in other cultures, toys are used to expand the development of a child's cognition in an idealistic fashion. In these communities, adults place the value of play with toys to be on the aspirations they set forth for their child. In the Western culture, the Barbie and Action-Man represent lifelike figures but in an imaginative state out of reach from the society of these children and adults. These toys give way to a unique world in which children's play is isolated and independent of the social constraints placed on society leaving the children free to delve into the imaginary and idealized version of what their development in life could be.[26]

Children may treat their toys in different ways based on their cultural practices. For example, children in certain communities may tend to be possessive of their toys, while children from other communities may be more willing to share. Favorite toys depend on familiar items in their environment, or their parents' interest, or the economic reality of the children's life. Children in an affluent society may enjoy board games or digital toys, whereas those living in poverty may find broken or lost items and those become their favorite playthings.[27]

Gender

Traditions within various cultures promote the passing down of certain toys to their children based on the child's gender. In Indigenous South American communities, boys receive a toy bow and arrow from their father while young girls receive a toy basket from their mother.[25] In North African and Saharan cultural communities, gender plays a role in the creation of self-made dolls. While female dolls are used to represent brides, mothers, and wives, male dolls are used to represent horsemen and warriors. This contrast stems from the various roles of men and women within the Saharan and North African communities. There are differences in the toys that are intended for girls and boys within various cultures, which is reflective of the differing roles of men and women within a specific cultural community.[26]

In the United States, certain toys, such as Barbie dolls and toy soldiers, are often perceived as being more acceptable for one gender than the other. Toy companies have often promoted the segregation by gender in toys because it enables them to customize the same toy for each gender, which ultimately doubles their revenue.

It has been noted that "Children as young as 18 months display sex-stereotyped toy choices."[28] These differences in toy choice are well established within the child by the age of three.[29]

From a different perspective, studies have shown that when young girls and boys were observed, toys rated with the best play quality, based on factors such as learning, problem solving, curiosity, creativity, imagination, and peer interaction, were those identified as the most gender neutral, such as building blocks and bricks along with pieces modeling people.[30] It has been suggested that allowing children to play with toys which more closely fit their talents would help them to better develop their skills.[31] Even as this debate is evolving and children are becoming more inclined to cross barriers in terms of gender with their toys, girls are typically more encouraged to do so than boys because of the societal value of masculinity.[32]

Economics

With toys comprising such a large and important part of human existence, the toy industry has a substantial economic impact. Sales of toys often increase around holidays where gift-giving is a tradition, such as Christmas.

Toy companies change and adapt their toys to meet the changing demands of children thereby gaining a larger share of the substantial market. In recent years many toys have become more complicated with flashing lights and sounds in an effort to appeal to children raised around television and the internet.

In an effort to reduce costs, many mass-producers of toys locate their factories in areas where wages are lower. For example, the majority of all toys sold in the U.S., for example, are manufactured in China.[22]

Many traditional toy makers have been losing sales to video game makers for years. Because of this, some traditional toy makers entered the field of electronic games, enhancing the brands that they have by introducing interactive extensions or internet connectivity to their existing toys.[33]

Safety regulations

Many countries have passed safety standards limiting the types of toys that can be sold. Most of these seek to limit potential hazards, such as choking or fire hazards that could cause injury. Children, especially very small ones, often put toys into their mouths, so the materials used to make a toy are regulated to prevent poisoning. Materials are also regulated to prevent fire hazards.

Every country has its own regulations on toy safety, but most of them try to harmonize their regulations. Since the most common danger for younger children is putting toys in their mouths, chemicals contained in paint and other components of children's products are carefully regulated. For example, while lead was a common ingredient in paint but this practice is now banned in the manufacture of toys.[34] The globalization of toys has had negative effects on locally-produced toys in various countries, pushing out traditional ways of play and presenting new risks to children in areas where parental literacy levels make it hard for parents to understand the risks and age-appropriateness of various imported toys.[35]

Toy use in animals

It is not unusual for some animals to play with toys. An example of this is a dolphin being trained to nudge a ball through a hoop. Young chimpanzees use sticks as dolls–the social aspect is seen by the fact that young females more often use a stick this way than young male chimpanzees.[36] They carry their chosen stick and put it in their nest. Such behavior is also seen in some adult female chimpanzees, but never after they have become mothers.[37]

Notes

- ↑ Amber Williams, FYI: What Is the Oldest Toy in the World? Popular Science, February 16, 2012. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ↑ toy Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ↑ Indus Valley Civilization Daily Life 3000-1500 B.C.E. Mr. Donn's Site. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Gaston Maspero, Amelia B. Edwards (trans.), Manual of Egyptian Archaeology and Guide to the Study of Antiquities in Egypt (Legare Street Press, 2021 (original 1887), ISBN 978-1013973710).

- ↑ Toby Wilkinson, Dictionary of Ancient Egypt (Thames & Hudson, 2008, ISBN 978-0500203965).

- ↑ Barry B. Powell, Classical Myth (Prentice Hall, 2000, ISBN 978-0130884428).

- ↑ James Gow, A Short History of Greek Mathematics (Cambridge University Press, 2010 (original 1884), ISBN 978-1108009034).

- ↑ Stephen Klein, "The making of children's culture" in Henry Jenkins (ed.), The Children's Culture Reader (New York University Press, 1998, ISBN 978-0814742327), 95–109.

- ↑ Francis Reginald Beaman Whitehouse, Table Games of Georgian and Victorian Days (Priory Press Ltd, 1971, ISBN 978-0850780192).

- ↑ Martin Fone, Curious Questions: Why do we call picture puzzles ‘jigsaws’? Country Life, June 6, 2020. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- ↑ Kristin Thompson, David Bordwell, and Jeff Smith, Film History: An Introduction, (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2021, ISBN 978-1260837476).

- ↑ Norman Joplin, Toy Soldiers (Courage Books, 1994, ISBN 978-1561384327).

- ↑ Professor Hoffmann, Puzzles Old and New (Forgotten Books, 2018 (original 1893), ISBN 978-0282566012).

- ↑ Erica Wagner, Peter Rabbit blazed a trail still well trod The Times, December 23, 2009. Retrieved February 11, 2023.

- ↑ Joy Lanzendorfer, How Beatrix Potter Invented Character Merchandising Smithsonian Magazine, January 31, 2017. Retrieved February 11, 2023.

- ↑ Rose & Morris Michtom (1870 - 1938) Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved February 11, 2023.

- ↑ Lawrence W. Reed, Child Labor and the British Industrial Revolution Mackinac Center for Public Policy, December 7, 2001. Retrieved February 11, 2023.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Rebecca C. Hains and Nancy A. Jennings (eds.), The Marketing of Children's Toys (Palgrave Macmillan, 2021, ISBN 978-3030628802).

- ↑ Silly Putty The Strong National Museum of Play. Retrieved February 11, 2023.

- ↑ Slinky The Strong National Museum of Play. Retrieved February 11, 2023.

- ↑ Sally Cartwrightm "Blocks and learning," Young Children 29(3) (March 1974): 141–146.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Doug Tsuruoka, "Toys: Not All Fun And Games," Investor's Business Daily, January 5, 2007.

- ↑ Mary Ucci, "Playdough: 50 Years' Old, And Still Gooey, Fun, And Educational," Child Health Alert 24 (April 2006).

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Margaret Webb Pressler, Bored with her toys The Washington Post, April 2, 2006. Retrieved February 11, 2023.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Peter K. Smith, Children and Play:Understanding Children's Worlds (Wiley-Blackwell, 2009, ISBN 978-0631235224).

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Jean-Pierre Rossie, Toys, Play, Culture, and Society: An Anthropological Approach with Reference to North Africa and the Sahara (Stockholm: SITREC, 2005).

- ↑ Gabriele Galimberti, Toy Stories: Photos of Children from Around the World and Their Favorite Things (Harry N. Abrams, 2014, ISBN 978-1419711749).

- ↑ Yvonne M. Caldera, Aletha C. Huston, and Marion O'Brien, "Social Interactions and Play Patterns of Parents and Toddlers with Feminine, Masculine, and Neutral Toys" Child Development 60(1) (1989): 70–76.

- ↑ G.M Alexander and J. Saenz, "Early androgens, activity levels and toy choices of children in the second year of life" Hormones and Behavior 62(4) (2012): 500–504.

- ↑ Jeffrey Trawick-Smith, Jennifer Wolff, Marley Koschel, and Jamie Marley, "Effects of Toys on the Play Quality of Preschool Children: Influence of Gender, Ethnicity, and Socioeconomic Status" Early Childhood Education Journal 43(4) (July 2015): 249–256.

- ↑ Carol J. Auster and Claire S. Mansbach, "The Gender Marketing of Toys: An Analysis of Color and Type of Toy on the Disney Store Website" Sex Roles 67(7) (October 2012): 375–388.

- ↑ Claire Cain Miller, Boys and Girls, Constrained by Toys and Costumes The New York Times, October 30, 2015. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ↑ Elissa Baxter, World in their hands The Age, March 26, 2007. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ↑ David Barboza, Why Lead in Toy Paint? It's Cheaper The New York Times, September 11, 2007. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ↑ Rebecca C. Hains and Nancy A. Jennings (eds.), The Marketing of Children's Toys (Palgrave Macmillan, 2022, ISBN 978-3030628833).

- ↑ Chimp "Girls" Play With "Dolls" Too—First Wild Evidence National Geographic, December 22, 2010. Retrieved February 12, 2023.

- ↑ Sonya M. Kahlenberg and Richard W. Wrangham, Sex differences in chimpanzees' use of sticks as play objects resemble those of children Current Biology 20(24) (2010): R1067–R1068. Retrieved February 12, 2023.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cannons, Helen Cox. The History of Toys. Capstone Global Library, 2020. ISBN 978-1474792622

- Galimberti, Gabriele. Toy Stories: Photos of Children from Around the World and Their Favorite Things. Harry N. Abrams, 2014. ISBN 978-1419711749

- Gow, James. A Short History of Greek Mathematics. Cambridge University Press, 2010 (original 1884). ISBN 978-1108009034

- Hains, Rebecca C., and Nancy A. Jennings (eds.). The Marketing of Children's Toys. Palgrave Macmillan, 2022, ISBN 978-3030628833

- Hoffmann, Professor. Puzzles Old and New. Forgotten Books, 2018 (original 1893). ISBN 978-0282566012

- Jenkins, Henry (ed.). The Children's Culture Reader. New York University Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0814742327

- Joplin, Norman. Toy Soldiers. Courage Books, 1994. ISBN 978-1561384327

- Maspero, Gaston, Amelia B. Edwards (trans.). Manual of Egyptian Archaeology and Guide to the Study of Antiquities in Egypt. Legare Street Press, 2021 (original 1887). ISBN 978-1013973710

- Rossie, Jean-Pierre. Toys, Play, Culture, and Society: An Anthropological Approach with Reference to North Africa and the Sahara. Stockholm: SITREC, 2005.

- Smith, Peter K. Children and Play:Understanding Children's Worlds. Wiley-Blackwell, 2009. ISBN 978-0631235224

- Thompson, Kristin, David Bordwell, and Jeff Smith. Film History: An Introductio. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2021. ISBN 978-1260837476

- Walsh, Tim. Timeless Toys: Classic Toys and the Playmakers Who Created Them. Andrews McMeel Publishing, 2005. ISBN 978-0740755712

- Whitehouse, Francis Reginald Beaman. Table Games of Georgian and Victorian Days. Priory Press Ltd, 1971., ISBN 978-0850780192

- Wilkinson, Toby. Dictionary of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson, 2008. ISBN 978-0500203965

External links

All links retrieved May 1, 2023.

- The Toys of our Childhood

- Toy story: A short history of awesome playthings National Geographic

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.