Tropical cyclone

- "Hurricane" and "Typhoon" redirect here.

A tropical cyclone is a meteorological term for a storm system characterized by a low pressure center and thunderstorms that produces strong wind and flooding rain. A tropical cyclone feeds on the heat released when moist air rises and the water vapor it contains condenses. They are fueled by a different heat mechanism than other cyclonic windstorms such as nor'easters, European windstorms, and polar lows, leading to their classification as "warm core" storm systems.

The adjective "tropical" refers to both the geographic origin of these systems, which form almost exclusively in tropical regions of the globe, and their formation in Maritime Tropical air masses. The noun "cyclone" refers to such storms' cyclonic nature, with counterclockwise rotation in the Northern Hemisphere and clockwise rotation in the Southern Hemisphere. Depending on their location and strength, tropical cyclones are referred to by various other names, such as hurricane, typhoon, tropical storm, cyclonic storm, and tropical depression.

While tropical cyclones can produce extremely powerful winds and torrential rain, they are also able to produce high waves and damaging storm surge. They develop over large bodies of warm water, and lose their strength if they move over land. This is the reason coastal regions can receive significant damage from a tropical cyclone, while inland regions are relatively safe from receiving strong winds. Heavy rains, however, can produce significant flooding inland, and storm surges can produce extensive coastal flooding up to 25 mi (40 km) from the coastline. Although their effects on human populations can be devastating, tropical cyclones can also relieve drought conditions. They also carry heat and energy away from the tropics and transport it towards temperate latitudes, which makes them an important part of the global atmospheric circulation mechanism. As a result, tropical cyclones help to maintain equilibrium in the Earth's troposphere, and to maintain a relatively stable and warm temperature worldwide.

Many tropical cyclones develop when the atmospheric conditions around a weak disturbance in the atmosphere are favorable. Others form when other types of cyclones acquire tropical characteristics. Tropical systems are then moved by steering winds in the troposphere; if the conditions remain favorable, the tropical disturbance intensifies, and can even develop an eye. On the other end of the spectrum, if the conditions around the system deteriorate or the tropical cyclone makes landfall, the system weakens and eventually dissipates.

Physical structure

All tropical cyclones are areas of low atmospheric pressure near the Earth's surface. The pressures recorded at the centers of tropical cyclones are among the lowest that occur on Earth's surface at sea level.[1] Tropical cyclones are characterized and driven by the release of large amounts of latent heat of condensation, which occurs when moist air is carried upwards and its water vapor condenses. This heat is distributed vertically around the center of the storm. Thus, at any given altitude (except close to the surface, where water temperature dictates air temperature) the environment inside the cyclone is warmer than its outer surroundings.[2]

Banding

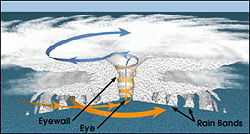

Rainbands are bands of showers and thunderstorms that spiral cyclonically toward the storm center. High wind gusts and heavy downpours often occur in individual rainbands, with relatively calm weather between bands. Tornadoes often form in the rainbands of landfalling tropical cyclones.[3] Intense annular tropical cyclones are distinctive for their lack of rainbands; instead, they possess a thick circular area of disturbed weather around their low pressure center.[4] While all surface low pressure areas require divergence aloft to continue deepening, the divergence over tropical cyclones is in all directions away from the center. The upper levels of a tropical cyclone feature winds directed away from the center of the storm with an anticyclonic rotation, due to the Coriolis effect. Winds at the surface are strongly cyclonic, weaken with height, and eventually reverse themselves. Tropical cyclones owe this unique characteristic to requiring a relative lack of vertical wind shear to maintain the warm core at the center of the storm.[5]

Eye and inner core

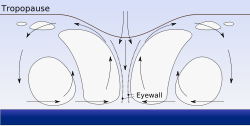

A strong tropical cyclone will harbor an area of sinking air at the center of circulation. If this area is strong enough, it can develop into an eye. Weather in the eye is normally calm and free of clouds, though the sea may be extremely violent.[3] The eye is normally circular in shape, and may range in size from 3 to 370 km (2–230 miles) in diameter. Intense, mature hurricanes can sometimes exhibit an inward curving of the eyewall's top, making it resemble a football stadium; this phenomenon is thus sometimes referred to as the stadium effect.[6]

There are other features that either surround the eye, or cover it. The central dense overcast is the concentrated area of strong thunderstorm activity near the center of a tropical cyclone.[7] The eyewall is a circle of strong thunderstorms that surrounds the eye; here is where the greatest wind speeds are found, where clouds reach the highest, and precipitation is the heaviest. The heaviest wind damage occurs where a hurricane's eyewall passes over land.[3] Associated with eyewalls are eyewall replacement cycles, which occur naturally in intense tropical cyclones. When cyclones reach peak intensity they usually—but not always—have an eyewall and radius of maximum winds that contract to a very small size, around 10–25 km (5 to 15 miles). At this point, some of the outer rainbands may organize into an outer ring of thunderstorms that slowly moves inward and robs the inner eyewall of its needed moisture and angular momentum. During this phase, the tropical cyclone weakens (i.e., the maximum winds die off somewhat and the central pressure goes up), but eventually the outer eyewall replaces the inner one completely. The storm can be of the same intensity as it was previously or, in some cases, it can be even stronger after the eyewall replacement cycle. Even if the cyclone is weaker at the end of the cycle, the storm may strengthen again as it builds a new outer ring for the next eyewall replacement.[8]

Size

The size of a tropical cyclone is determined by measuring the distance from their center of circulation to their outermost closed isobar. If the radius is less than two degrees of latitude (120 nm, 222 km), then the cyclone is "very small" or a "midget." Radii of 2–3 degrees (120–180 nm, 222–333 km) are considered "small." Radii between 3 and 6 latitude degrees (180–360 nm, 333–666 km) are considered "average sized." Tropical cyclones are considered "large" when the closed isobar radius is 6–8 degrees of latitude (360–480 nm, 666–888 km), while "very large" tropical cyclones have a radius of greater than 8 degrees (480 nm, 888 km). Other methods of determining a tropical cyclone's size include measuring the radius of gale force winds and measuring the radius of the central dense overcast.

Mechanics

A tropical cyclone's primary energy source is the release of the heat of condensation from water vapor condensing at high altitudes, with solar heating being the initial source for evaporation. Therefore, a tropical cyclone can be visualized as a giant vertical heat engine supported by mechanics driven by physical forces such as the rotation and gravity of the Earth. In another way, tropical cyclones could be viewed as a special type of mesoscale convective complex, which continues to develop over a vast source of relative warmth and moisture. Condensation leads to higher wind speeds, as a tiny fraction of the released energy is converted into mechanical energy;[9] the faster winds and lower pressure associated with them in turn cause increased surface evaporation and thus even more condensation. Much of the released energy drives updrafts that increase the height of the storm clouds, speeding up condensation. This gives rise to factors that provide the system with enough energy to be self-sufficient, and cause a positive feedback loop that continues as long as the tropical cyclone can draw energy from a thermal reservoir. In this case, the heat source is the warm water at the surface of the ocean. Factors such as a continued lack of equilibrium in air mass distribution would also give supporting energy to the cyclone. The rotation of the Earth causes the system to spin, an effect known as the Coriolis effect, giving it a cyclonic characteristic and affecting the trajectory of the storm.

What primarily distinguishes tropical cyclones from other meteorological phenomena is the energy source. The tropical cyclone gains energy from the warm waters of the tropics through the latent heat of condensation.[10] Because convection is strongest in a tropical climate, it defines the initial domain of the tropical cyclone. By contrast, mid-latitude cyclones draw their energy mostly from pre-existing horizontal temperature gradients in the atmosphere. To continue to drive its heat engine, a tropical cyclone must remain over warm water, which provides the needed atmospheric moisture to maintain the positive feedback loop running. As a result, when a tropical cyclone passes over land, it is cut off from its heat source and its strength diminishes rapidly.[11]

The passage of a tropical cyclone over the ocean can cause the upper layers of the ocean to cool substantially, which can influence subsequent cyclone development. Cooling is primarily caused by upwelling of cold water from deeper in the ocean due to the wind stresses the storm itself induces upon the sea surface. Additional cooling may come in the form of cold water from falling raindrops. Cloud cover may also play a role in cooling the ocean, by shielding the ocean surface from direct sunlight before and slightly after the storm passage. All these effects can combine to produce a dramatic drop in sea surface temperature over a large area in just a few days.[12]

While the most obvious motion of clouds is toward the center, tropical cyclones also develop an upper-level (high-altitude) outward flow of clouds. These originate from air that has released its moisture and is expelled at high altitude through the "chimney" of the storm engine. This outflow produces high, thin cirrus clouds that spiral away from the center. These high cirrus clouds may be the first signs of an approaching tropical cyclone when seen from dry land.[12]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

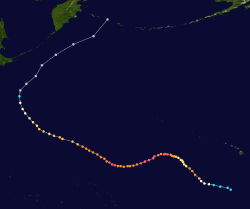

Map of the cumulative tracks of all tropical cyclones during the 1985–2005 time period. The Pacific Ocean west of the International Date Line sees more tropical cyclones than any other basin, while there is almost no activity in the Atlantic Ocean south of the Equator. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

There are six Regional Specialized Meteorological Centres (RSMCs) worldwide. These organizations are designated by the World Meteorological Organization and are responsible for tracking and issuing bulletins, warnings, and advisories about tropical cyclones in their designated areas of responsibility. Additionally, there are six Tropical Cyclone Warning Centres (TCWCs) that provide information to smaller regions. The RSMCs and TCWCs, however, are not the only organizations that provide information about tropical cyclones to the public. The Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) issues informal advisories in all basins except the Northern Atlantic and Northeastern Pacific. The Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) issues informal advisories and names for tropical cyclones that approach the Philippines in the Northwestern Pacific. The Canadian Hurricane Centre (CHC) issues advisories on hurricanes and their remnants when they affect Canada.

Formation

Times

Worldwide, tropical cyclone activity peaks in late summer, when the difference between temperatures aloft and sea surface temperatures is the greatest. However, each particular basin has its own seasonal patterns. On a worldwide scale, May is the least active month, while September is the most active.[13]

In the North Atlantic, a distinct hurricane season occurs from June 1 to November 30, sharply peaking from late August through September.[13] The statistical peak of the North Atlantic hurricane season is September 10. The Northeast Pacific has a broader period of activity, but in a similar time frame to the Atlantic.[14] The Northwest Pacific sees tropical cyclones year-round, with a minimum in February and a peak in early September. In the North Indian basin, storms are most common from April to December, with peaks in May and November.[13]

In the Southern Hemisphere, tropical cyclone activity begins in late October and ends in May. Southern Hemisphere activity peaks in mid-February to early March.[13]

| Season lengths and seasonal averages[13] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basin | Season start | Season end | Tropical Storms (>34 knots) |

Tropical Cyclones (>63 knots) |

Category 3+ TCs (>95 knots) |

| Northwest Pacific | April | January | 26.7 | 16.9 | 8.5 |

| South Indian | October | May | 20.6 | 10.3 | 4.3 |

| Northeast Pacific | May | November | 16.3 | 9.0 | 4.1 |

| North Atlantic | June | November | 10.6 | 5.9 | 2.0 |

| Australia Southwest Pacific | October | May | 10.6 | 4.8 | 1.9 |

| North Indian | April | December | 5.4 | 2.2 | 0.4 |

Factors

The formation of tropical cyclones is the topic of extensive ongoing research and is still not fully understood. While six factors appear to be generally necessary, tropical cyclones may occasionally form without meeting all of the following conditions. In most situations, water temperatures of at least 26.5 °C (80 °F) are needed down to a depth of at least 50 m (150 feet). Waters of this temperature cause the overlying atmosphere to be unstable enough to sustain convection and thunderstorms. Another factor is rapid cooling with height. This allows the release of latent heat, which is the source of energy in a tropical cyclone. High humidity is needed, especially in the lower-to-mid troposphere; when there is a great deal of moisture in the atmosphere, conditions are more favorable for disturbances to develop. Low amounts of wind shear are needed, as when shear is high, the convection in a cyclone or disturbance will be disrupted, preventing formation of the feedback loop. Tropical cyclones generally need to form more than 500 km (310 miles) or 5 degrees of latitude away from the equator. This allows the Coriolis effect to deflect winds blowing towards the low pressure center, causing a circulation. Lastly, a formative tropical cyclone needs a pre-existing system of disturbed weather. The system must have some sort of circulation as well as a low pressure center.[15]

Locations

Most tropical cyclones form in a worldwide band of thunderstorm activity called by several names: the Intertropical Discontinuity (ITD), the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), or the monsoon trough. Another important source of atmospheric instability is found in tropical waves, which cause about 85 percent of intense tropical cyclones in the Atlantic Ocean and become most of the tropical cyclones in the Eastern Pacific basin.[16]

Tropical cyclones originate on the eastern side of oceans, but move west, intensifying as they move. Most of these systems form between 10 and 30 degrees away of the equator, and 87 percent form no farther away than 20 degrees of latitude, north or south. Because the Coriolis effect initiates and maintains tropical cyclone rotation, tropical cyclones rarely form or move within about 5 degrees of the equator, where the Coriolis effect is weakest. However, it is possible for tropical cyclones to form within this boundary as Tropical Storm Vamei did in 2001 and Cyclone Agni in 2004.

Movement and track

Steering winds

Although tropical cyclones are large systems generating enormous energy, their movements over the Earth's surface are controlled by large-scale winds—the streams in the Earth's atmosphere. The path of motion is referred to as a tropical cyclone's track.

Tropical systems, while generally located equatorward of the 20th parallel, are steered primarily westward by the east-to-west winds on the equatorward side of the subtropical ridge—a persistent high pressure area over the world's oceans. In the tropical North Atlantic and Northeast Pacific oceans, trade winds—another name for the westward-moving wind currents—steer tropical waves westward from the African coast and towards the Caribbean Sea, North America, and ultimately into the central Pacific Ocean before the waves dampen out. These waves are the precursors to many tropical cyclones within this region. In the Indian Ocean and Western Pacific (both north and south of the equator), tropical cyclogenesis is strongly influenced by the seasonal movement of the Intertropical Convergence Zone and the monsoon trough, rather than by easterly waves.

Coriolis effect

The Earth's rotation imparts an acceleration known as the Coriolis Effect, Coriolis Acceleration, or colloquially, Coriolis Force. This acceleration causes cyclonic systems to turn towards the poles in the absence of strong steering currents. The poleward portion of a tropical cyclone contains easterly winds, and the Coriolis effect pulls them slightly more poleward. The westerly winds on the equatorward portion of the cyclone pull slightly towards the equator, but, because the Coriolis effect weakens toward the equator, the net drag on the cyclone is poleward. Thus, tropical cyclones in the Northern Hemisphere usually turn north (before being blown east), and tropical cyclones in the Southern Hemisphere usually turn south (before being blown east) when no other effects counteract the Coriolis effect.

The Coriolis effect also initiates cyclonic rotation, but it is not the driving force that brings this rotation to high speeds. These speeds instead result from conservation of angular momentum. This means that air is drawn in from an area much larger than the cyclone such that the tiny rotational speed (originally imparted by the Coriolis effect) is magnified greatly as the air is drawn into the low pressure center.

Interaction with the mid-latitude westerlies

When a tropical cyclone crosses the subtropical ridge axis, its general track around the high-pressure area is deflected significantly by winds moving towards the general low-pressure area to its north. When the cyclone track becomes strongly poleward with an easterly component, the cyclone has begun recurvature.[17] A typhoon moving through the Pacific Ocean towards Asia, for example, will recurve offshore of Japan to the north, and then to the northeast, if the typhoon encounters winds blowing northeastward toward a low-pressure system passing over China or Siberia. Many tropical cyclones are eventually forced toward the northeast by extratropical cyclones, which move from west to east to the north of the subtropical ridge.

Landfall

Officially, landfall is when a storm's center (the center of its circulation, not its edge) crosses the coastline. Storm conditions may be experienced on the coast and inland hours before landfall; in fact, a tropical cyclone can launch its strongest winds over land, yet not make landfall; if this occurs, then it is said that the storm made a direct hit on the coast. Due to this definition, the landfall area experiences half of a land-bound storm by the time the actual landfall occurs. For emergency preparedness, actions should be timed from when a certain wind speed or intensity of rainfall will reach land, not from when landfall will occur.[18]

Dissipation

Factors

A tropical cyclone can cease to have tropical characteristics through several different ways. One such way is if it moves over land, thus depriving it of the warm water it needs to power itself, quickly losing strength. Most strong storms lose their strength very rapidly after landfall and become disorganized areas of low pressure within a day or two, or evolve into extratropical cyclones. While there is a chance a tropical cyclone could regenerate it managed to get back over open warm water, if it remains over mountains for even a short time, it can rapidly lose its structure. Many storm fatalities occur in mountainous terrain, as the dying storm unleashes torrential rainfall, leading to deadly floods and mudslides, similar to those that happened with Hurricane Mitch in 1998. Additionally, dissipation can occur if a storm remains in the same area of ocean for too long, mixing the upper 30 meters (100 feet) of water. This occurs because the cyclone draws up colder water from deeper in the sea through upwelling, and causes the water surface to become too cool to support the storm. Without warm surface water, the storm cannot survive.

A tropical cyclone can dissipate when it moves over waters significantly below 26.5 °C. This will cause the storm to lose its tropical characteristics (i.e., thunderstorms near the center and warm core) and become a remnant low pressure area, which can persist for several days. This is the main dissipation mechanism in the Northeast Pacific ocean. Weakening or dissipation can occur if it experiences vertical wind shear, causing the convection and heat engine to move away from the center; this normally ceases development of a tropical cyclone.[19] Additionally, its interaction with the main belt of the Westerlies, by means of merging with a nearby frontal zone, can cause tropical cyclones to evolve into extratropical cyclones. Even after a tropical cyclone is said to be extratropical or dissipated, it can still have tropical storm force (or occasionally hurricane force) winds and drop several inches of rainfall. In the Pacific ocean and Atlantic ocean, such tropical-derived cyclones of higher latitudes can be violent and may occasionally remain at hurricane-force wind speeds when they reach the west coast of North America. These phenomena can also affect Europe, where they are known as European windstorms; Hurricane Iris's extratropical remnants became one in 1995.[20] Additionally, a cyclone can merge with another area of low pressure, becoming a larger area of low pressure. This can strengthen the resultant system, although it may no longer be a tropical cyclone.[19]

Artificial dissipation

In the 1960s and 1970s, the United States government attempted to weaken hurricanes through Project Stormfury by seeding selected storms with silver iodide. It was thought that the seeding would cause supercooled water in the outer rainbands to freeze, causing the inner eyewall to collapse and thus reducing the winds. The winds of Hurricane Debbie—a hurricane seeded in Project Stormfury—dropped as much as 30%, but Debby regained its strength after each of two seeding forays. In an earlier episode in 1947, disaster struck when a hurricane east of Jacksonville, Florida promptly changed its course after being seeded, and smashed into Savannah, Georgia.[21] Because there was so much uncertainty about the behavior of these storms, the federal government would not approve seeding operations unless the hurricane had a less than 10 percent chance of making landfall within 48 hours, greatly reducing the number of possible test storms. The project was dropped after it was discovered that eyewall replacement cycles occur naturally in strong hurricanes, casting doubt on the result of the earlier attempts. Today, it is known that silver iodide seeding is not likely to have an effect because the amount of supercooled water in the rainbands of a tropical cyclone is too low.[9]

Other approaches have been suggested over time, including cooling the water under a tropical cyclone by towing icebergs into the tropical oceans. Other ideas range from covering the ocean in a substance that inhibits evaporation, dropping large quantities of ice into the eye at very early stages of development (so that the latent heat is absorbed by the ice, instead of being converted to kinetic energy that would feed the positive feedback loop), or blasting the cyclone apart with nuclear weapons.[9] Project Cirrus even involved throwing dry ice on a cyclone.[22] These approaches all suffer from the same flaw: tropical cyclones are simply too large for any of them to be practical.[9]

Effects

Tropical cyclones out at sea cause large waves, heavy rain, and high winds, disrupting international shipping and, at times, causing shipwrecks. Tropical cyclones stir up water, leaving a cool wake behind them, which causes the region to be less favorable for subsequent tropical cyclones. On land, strong winds can damage or destroy vehicles, buildings, bridges, and other outside objects, turning loose debris into deadly flying projectiles. The storm surge, or the increase in sea level due to the cyclone, is typically the worst effect from landfalling tropical cyclones, historically resulting in 90 percent of tropical cyclone deaths.[23] The broad rotation of a landfalling tropical cyclone, and vertical wind shear at its periphery, spawns tornadoes. Tornadoes can also be spawned as a result of eyewall mesovortices, which persist until landfall.

Within the last two centuries, tropical cyclones have been responsible for the deaths of about 1.9 million persons worldwide. Large areas of standing water caused by flooding lead to infection, as well as contributing to mosquito-borne illnesses. Crowded evacuees in shelters increase the risk of disease propagation. Tropical cyclones significantly interrupt infrastructure, leading to power outages, bridge destruction, and hamper reconstruction efforts.[23]

Although cyclones take an enormous toll in lives and personal property, they may be important factors in the precipitation regimes of places they impact, as they may bring much-needed precipitation to otherwise dry regions.[24] Tropical cyclones also help maintain the global heat balance by moving warm, moist tropical air to the middle latitudes and polar regions. The storm surge and winds of hurricanes may be destructive to human-made structures, but they also stir up the waters of coastal estuaries, which are typically important fish breeding locales. Tropical cyclone destruction spurs redevelopment, greatly increasing local property values.[25]

Observation and forecasting

Observation

Intense tropical cyclones pose a particular observation challenge. As they are a dangerous oceanic phenomenon and are relatively small, weather stations are rarely available on the site of the storm itself. Surface observations are generally available only if the storm is passing over an island or a coastal area, or if there is a nearby ship. Usually, real-time measurements are taken in the periphery of the cyclone, where conditions are less catastrophic and its true strength cannot be evaluated. For this reason, there are teams of meteorologists that move into the path of tropical cyclones to help evaluate their strength at the point of landfall.

Tropical cyclones far from land are tracked by weather satellites capturing visible and infrared images from space, usually at half-hour to quarter-hour intervals. As a storm approaches land, it can be observed by land-based Doppler radar. Radar plays a crucial role around landfall because it shows a storm's location and intensity minute by minute.

In-situ measurements, in real-time, can be taken by sending specially equipped reconnaissance flights into the cyclone. In the Atlantic basin, these flights are regularly flown by United States government hurricane hunters.[26] The aircraft used are WC-130 Hercules and WP-3D Orions, both four-engine turboprop cargo aircraft. These aircraft fly directly into the cyclone and take direct and remote-sensing measurements. The aircraft also launch GPS dropsondes inside the cyclone. These sondes measure temperature, humidity, pressure, and especially winds between flight level and the ocean's surface. A new era in hurricane observation began when a remotely piloted Aerosonde, a small drone aircraft, was flown through Tropical Storm Ophelia as it passed Virginia's Eastern Shore during the 2005 hurricane season. A similar mission was also completed successfully in the western Pacific ocean. This demonstrated a new way to probe the storms at low altitudes that human pilots seldom dare.

Forecasting

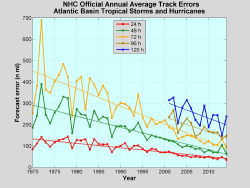

Because of the forces that affect tropical cyclone tracks, accurate track predictions depend on determining the position and strength of high- and low-pressure areas, and predicting how those areas will change during the life of a tropical system. The deep layer mean flow is considered to be the best tool in determining track direction and speed. If storms are significantly sheared, use of wind speed measurements at a lower altitude, such as at the 700 hpa pressure surface (3000 meters or 10000 feet above sea level) will produce better predictions. High-speed computers and sophisticated simulation software allow forecasters to produce computer models that predict tropical cyclone tracks based on the future position and strength of high- and low-pressure systems. Combining forecast models with increased understanding of the forces that act on tropical cyclones, as well as with a wealth of data from Earth-orbiting satellites and other sensors, scientists have increased the accuracy of track forecasts over recent decades. However, scientists say they are less skillful at predicting the intensity of tropical cyclones.[27] They attribute the lack of improvement in intensity forecasting to the complexity of tropical systems and an incomplete understanding of factors that affect their development.

Classifications, terminology, and naming

Intensity classifications

Tropical cyclones are classified into three main groups, based on intensity: tropical depressions, tropical storms, and a third group of more intense storms, whose name depends on the region. For example, if a tropical storm in the Northwest Pacific reaches hurricane-strength winds on the Beaufort scale, it is referred to as a typhoon; if a tropical storm passes the same benchmark in the Northeast Pacific Ocean, or in the Atlantic, it is called a hurricane. Neither "hurricane" nor "typhoon" is used in the South Pacific.

Additionally, as indicated in the table below, each basin uses a separate system of terminology, making comparisons between different basins difficult. In the Pacific Ocean, hurricanes from the Central North Pacific sometimes cross the International Date Line into the Northwest Pacific, becoming typhoons (such as Hurricane/Typhoon Ioke in 2006); on rare occasions, the reverse will occur. It should also be noted that typhoons with sustained winds greater than 130 knots (240 km/h or 150 mph) are called Super Typhoons by the Joint Typhoon Warning Center.[28]

A tropical depression is an organized system of clouds and thunderstorms with a defined surface circulation and maximum sustained winds of less than 17 m/s (33 kt, 38 mph, or 62 km/h). It has no eye and does not typically have the organization or the spiral shape of more powerful storms. However, it is already a low-pressure system, hence the name "depression." The practice of the Philippines is to name tropical depressions from their own naming convention when the depressions are within the Philippines' area of responsibility.

A tropical storm is an organized system of strong thunderstorms with a defined surface circulation and maximum sustained winds between 17 and 32 m/s (34–63 kt, 39–73 mph, or 62–117 km/h). At this point, the distinctive cyclonic shape starts to develop, although an eye is not usually present. Government weather services, other than the Philippines, first assign names to systems that reach this intensity (thus the term named storm).

A hurricane or typhoon (sometimes simply referred to as a tropical cyclone, as opposed to a depression or storm) is a system with sustained winds of at least 33 m/s (64 kt, 74 mph, or 118 km/h). A cyclone of this intensity tends to develop an eye, an area of relative calm (and lowest atmospheric pressure) at the center of circulation. The eye is often visible in satellite images as a small, circular, cloud-free spot. Surrounding the eye is the eyewall, an area about 16–80 km (10–50 mi) wide in which the strongest thunderstorms and winds circulate around the storm's center. Maximum sustained winds in the strongest tropical cyclones have been estimated at over 200 mph.[29]

| Tropical Cyclone Classifications (all winds are 10-minute averages) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beaufort scale | 10-minute sustained winds (knots) | N Indian Ocean IMD |

SW Indian Ocean MF |

Australia BOM |

SW Pacific FMS |

NW Pacific JMA |

NW Pacific JTWC |

NE Pacific & N Atlantic NHC & CPHC |

| 0–6 | <28 | Depression | Trop. Disturbance | Tropical Low | Tropical Depression | Tropical Depression | Tropical Depression | Tropical Depression |

| 7 | 28-29 | Deep Depression | Depression | |||||

| 30-33 | Tropical Storm | Tropical Storm | ||||||

| 8–9 | 34–47 | Cyclonic Storm | Moderate Tropical Storm | Trop. Cyclone (1) | Tropical Cyclone | Tropical Storm | ||

| 10 | 48–55 | Severe Cyclonic Storm | Severe Tropical Storm | Tropical Cyclone (2) | Severe Tropical Storm | |||

| 11 | 56–63 | Typhoon | Hurricane (1) | |||||

| 12 | 64–72 | Very Severe Cyclonic Storm | Tropical Cyclone | Severe Tropical Cyclone (3) | Typhoon | |||

| 73–85 | Hurricane (2) | |||||||

| 86–89 | Severe Tropical Cyclone (4) | Major Hurricane (3) | ||||||

| 90–99 | Intense Tropical Cyclone | |||||||

| 100–106 | Major Hurricane (4) | |||||||

| 107-114 | Severe Tropical Cyclone (5) | |||||||

| 115–119 | Very Intense Tropical Cyclone | Super Typhoon | ||||||

| >120 | Super Cyclonic Storm | Major Hurricane (5) | ||||||

Origin of storm terms

The word typhoon used today in the Northwest Pacific, has two possible and equally plausible origins. The first is from the Chinese 大風 (Cantonese: daaih fūng; Mandarin: dà fēng) which means "great wind." (The Chinese term as 颱風 or 台风 táifēng, and 台風 taifū in Japanese, has an independent origin traceable variously to 風颱, 風篩 or 風癡 hongthai, going back to Song 宋 (960-1278) and Yuan 元 (1260-1341) dynasties. The first record of the character 颱 appeared in the 1685 edition of Summary of Taiwan 臺灣記略).[30]

Alternatively, the word may be derived from Urdu, Persian and Arabic ţūfān (طوفان), which in turn originates from Greek tuphōn (Τυφών), a monster in Greek mythology responsible for hot winds. The related Portuguese word tufão, used in Portuguese for any tropical cyclone, is also derived from Greek tuphōn.[31]

The word hurricane, used in the North Atlantic and Northeast Pacific, is derived from the Taino name for the Carib Amerindian god of evil, Huricán, which was derived from the Mayan god of wind, storm, and fire, "Huracán." This became the Spanish huracán, which became "hurricane" in English.[32]

Naming

Storms reaching tropical storm strength were initially given names to eliminate confusion when there are multiple systems in any individual basin at the same time which assists in warning people of the coming storm.[33] In most cases, a tropical cyclone retains its name throughout its life; however, under special circumstances, tropical cyclones may be renamed while active. These names are taken from lists which vary from region to region and are drafted a few years ahead of time. The lists are decided upon, depending on the regions, either by committees of the World Meteorological Organization (called primarily to discuss many other issues), or by national weather offices involved in the forecasting of the storms. Each year, the names of particularly destructive storms (if there are any) are "retired" and new names are chosen to take their place.

Notable tropical cyclones

Tropical cyclones that cause extreme destruction are rare, though when they occur, they can cause great amounts of damage or thousands of fatalities.

The 1970 Bhola cyclone is the deadliest tropical cyclone on record, killing over 300,000 people after striking the densely populated Ganges Delta region of Bangladesh on November 13, 1970.[34] Its powerful storm surge was responsible for the high death toll. The Hugli River Cyclone (the Hooghly River or Calcutta Cyclone) has been described as "one of the deadliest natural disasters of all time." Making landfall on October 11, 1737 in the Ganges River Delta, the storm tracked approximately 330 km inland before dissipating. Due to storm surge and floods, between 300,000 and 350,000 people died.[34] The North Indian cyclone basin has historically been the deadliest basin, with several cyclones since 1900 killing over 100,000 people, all in Bangladesh.[23] The Great Hurricane of 1780 is the deadliest Atlantic hurricane on record, killing about 22,000 people in the Lesser Antilles.[35]

A tropical cyclone does need not be particularly strong to cause memorable damage, especially if the deaths are from rainfall or mudslides. For example, Tropical Storm Thelma in November 1991 killed thousands in the Philippines, where it was known as Uring. [36]

Hurricane Katrina is estimated as the costliest tropical cyclone worldwide, as it struck the Bahamas, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama in 2005, causing $81.2 billion in property damage (2005 USD) with overall damage estimates exceeding $100 billion (2005 USD).[34] Katrina killed at least 1,836 people after striking Louisiana and Mississippi as a major hurricane in August 2005. Hurricane Iniki in 1992 was the most powerful storm to strike Hawaii in recorded history, hitting Kauai as a Category 4 hurricane, killing six people, and causing U.S. $3 billion in damage.

In the most recent and reliable records, most tropical cyclones which attained a pressure of 900 hPa (mbar) (26.56 inHg) or less occurred in the Western North Pacific Ocean. The strongest tropical cyclone recorded worldwide, as measured by minimum central pressure, was Typhoon Tip, which reached a pressure of 870 hPa (25.69 inHg) on October 12, 1979. On October 23, 2015, Hurricane Patricia attained the strongest 1-minute sustained winds on record at 215 mph (345 km/h).[37]

Miniature Cyclone Tracy was roughly 100 km (60 miles) wide before striking Darwin, Australia in 1974, holding the record for the smallest tropical cyclone until 2008 when it was unseated by tropical cyclone Marco. Marco had gale force winds that extended just 19 kilometers (12 miles).[38]

Hurricane John is the longest-lasting tropical cyclone on record, lasting 30 days in 1994, and traveling 8,188 statute miles. The deadliest hurricane on record in Puerto Rico was also the longest-lasting Atlantic tropical cyclone: 1899 San Ciriaco Hurricane was a tropical cyclone for 27.75 days.[39]

Long term activity trends

While the number of storms in the Atlantic has increased since 1995, there is no obvious global trend; the annual number of tropical cyclones worldwide remains about 87 ± 10. However, the ability of climatologists to make long-term data analysis in certain basins is limited by the lack of reliable historical data in some basins, primarily in the Southern Hemisphere.[40] In spite of that, there is some evidence that the intensity of hurricanes is increasing:

Records of hurricane activity worldwide show an upswing of both the maximum wind speed in and the duration of hurricanes. The energy released by the average hurricane (again considering all hurricanes worldwide) seems to have increased by around 70 percent in the past 30 years or so, corresponding to about a 15 percent increase in the maximum wind speed and a 60 percent increase in storm lifetime.[41]

Atlantic storms are becoming more destructive financially, since five of the ten most expensive storms in United States history have occurred since 1990. This can be attributed to the increased intensity and duration of hurricanes striking North America,[41] and to a greater degree, the number of people living in susceptible coastal areas, following increased development in the region since the last surge in Atlantic hurricane activity in the 1960s. Often in part because of the threat of hurricanes, many coastal regions had sparse population between major ports until the advent of automobile tourism; therefore, the most severe portions of hurricanes striking the coast may have gone unmeasured in some instances. The combined effects of ship destruction and remote landfall severely limit the number of intense hurricanes in the official record before the era of hurricane reconnaissance aircraft and satellite meteorology.

The number and strength of Atlantic hurricanes may undergo a 50-70 year cycle, also known as the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation.[42] Although more common since 1995, few above-normal hurricane seasons occurred during 1970-1994. Destructive hurricanes struck frequently from 1926-1960, including many major New England hurricanes. A record 21 Atlantic tropical storms formed in 1933, a record only recently exceeded in 2005, which saw 28 storms. Tropical hurricanes occurred infrequently during the seasons of 1900-1925; however, many intense storms formed 1870-1899. During the 1887 season, 19 tropical storms formed, of which a record 4 occurred after 1 November and 11 strengthened into hurricanes. Few hurricanes occurred in the 1840s to 1860s; however, many struck in the early 1800s, including an 1821 storm that made a direct hit on New York City.

These active hurricane seasons predated satellite coverage of the Atlantic basin. Before the satellite era began in 1960, tropical storms or hurricanes went undetected unless a ship reported a voyage through the storm or a storm hit land in a populated area. The official record, therefore, could miss storms in which no ship experienced gale-force winds, recognized it as a tropical storm (as opposed to a high-latitude extra-tropical cyclone, a tropical wave, or a brief squall), returned to port, and reported the experience.

Global warming

In an article in Nature, Kerry Emanuel stated that potential hurricane destructiveness, a measure combining hurricane strength, duration, and frequency, "is highly correlated with tropical sea surface temperature, reflecting well-documented climate signals, including multidecadal oscillations in the North Atlantic and North Pacific, and global warming." Emanuel predicted "a substantial increase in hurricane-related losses in the twenty-first century.[43] Similarly, P.J. Webster and others published an article in Science examining the "changes in tropical cyclone number, duration, and intensity" over the last 35 years, the period when satellite data has been available. Their main finding was although the number of cyclones decreased throughout the planet excluding the north Atlantic Ocean, there was a great increase in the number and proportion of very strong cyclones.[44] Sea surface temperature is vital in the development of cyclones. Though neither study can directly link hurricanes with global warming, the increase in sea surface temperatures is believed to be due to both global warming and nature variability, such as the hypothesized Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO), though an exact attribution has not been defined.[45]

The U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory performed a simulation to determine if there is a statistical trend in the frequency or strength of cyclones over time. They were unable to draw definite conclusions:

In summary, neither our model projections for the 21st century nor our analyses of trends in Atlantic hurricane and tropical storm activity support the notion that greenhouse gas-induced warming leads to large increases in either tropical storm or overall hurricane numbers in the Atlantic. ...Therefore, we conclude that it is premature to conclude with high confidence that human activity–and particularly greenhouse warming–has already caused a detectable change in Atlantic hurricane activity. ... We also conclude that it is likely that climate warming will cause Atlantic hurricanes in the coming century have higher rainfall rates than present-day hurricanes, and medium confidence that they will be more intense (higher peak winds and lower central pressures) on average.[46]

There is no universal agreement about the magnitude of the effects anthropogenic global warming has on tropical cyclone formation, track, and intensity. For example, critics such as Chris Landsea assert that:

While it is possible that the recorded increase in short-duration TCs [tropical cyclones]represents a real climate signal, ... it is more plausible that the increase arises primarily from improvements in the quantity and quality of observations, along with enhanced interpretation techniques.[47]

Albeit many aspects of a link between tropical cyclones and global warming have continued to be hotly debated. One point of agreement is that no individual tropical cyclone or season can be attributed to global warming.[45]

Related cyclone types

In addition to tropical cyclones, there are two other classes of cyclones within the spectrum of cyclone types. These kinds of cyclones, known as extratropical cyclones and subtropical cyclones, can be stages a tropical cyclone passes through during its formation or dissipation.[48]

An extratropical cyclone is a storm that derives energy from horizontal temperature differences, which are typical in higher latitudes. A tropical cyclone can become extratropical as it moves toward higher latitudes if its energy source changes from heat released by condensation to differences in temperature between air masses;[2] additionally, although not as frequently, an extratropical cyclone can transform into a subtropical storm, and from there into a tropical cyclone. From space, extratropical storms have a characteristic "comma-shaped" cloud pattern. Extratropical cyclones can also be dangerous when their low-pressure centers cause powerful winds and very high seas.

A subtropical cyclone is a weather system that has some characteristics of a tropical cyclone and some characteristics of an extratropical cyclone. They can form in a wide band of latitudes, from the equator to 50°. Although subtropical storms rarely have hurricane-force winds, they may become tropical in nature as their cores warm.[2] From an operational standpoint, a tropical cyclone is usually not considered to become subtropical during its extratropical transition.

In popular culture

In popular culture, tropical cyclones have made appearances in different types of media, including films, books, television, music, and electronic games. The media can have tropical cyclones that are entirely fictional, or can be based on real events. For example, George Rippey Stewart's Storm, a best-seller published in 1941, is thought to have influenced meteorologists into giving female names to Pacific tropical cyclones.[49] Another example is the hurricane in The Perfect Storm, which describes the sinking of the Andrea Gail by the 1991 Halloween Nor'easter.[50]

In the 2004 film The Day After Tomorrow the most severe of the weather anomalies are three hurricane-like super storms that cover nearly the entire northern hemisphere. As a reaction to the global warming that has occurred, the the Atlantic Ocean reaches a critical desalinization point and extreme weather begins across the globe. The three massive cyclonic storms amass over Canada, Europe and Siberia, wreaking havoc over whatever crosses their path. The scientists tracking the weather discover that the deadliest part, the eye of the storm, pulls super cooled air from the upper troposphere down to ground level too fast for it to warm up, subsequently freezing anything and everything. Thus the eyes of these storm systems are responsible for the highest death tolls out of all the natural disasters occurring around the world. It should be noted that is in fact not possible for super-storms like these to actually retrieve air from the upper layers of the atmosphere and pull it down to ground level in a manner that would allow to remain super-cool.

Notes

- ↑ Steve Symonds, Highs and Lows Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 2003. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Types of Storms NOAA's Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 National Weather Service, Tropical Cyclone Structure. National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ John A. Knaff, James P. Kossin, and Mark DeMaria, Annular Hurricanes. Weather and Forecasting. 18(2) (2003):204-223. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ R. Craig Kochel, Victor R. Baker, and Peter C. Patton, Flood Geomorphology (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Interscience, 1988, ISBN 0471625582).

- ↑ Judson Jones, Hurricane categories and other terminology explained CNN, September 5, 2018. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ American Meteorological Society, central dense overcast. Meteorology Glossary. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ Jeff Haby, Eyewall Replacement Cycle TheWeatherPrediction.com. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Other Common Misconceptions About Hurricane Mitigation: Nuclear Weapons NOAA's Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ Megan Mulford, What is the Difference Between Hurricanes and Mid-Latitude Cyclones? Weatherology, February 22, 2018.

- ↑ Anatomy and Lifecycle of a Storn NOAA's Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Joe Cione, How does the ocean respond to a hurricane and how does this feedback to the storm itself? Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 Hurricane Season Information NOAA's Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ Tropical Cyclone Climatology. National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ How do hurricanes form? National Weather Service. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ Tropical Definitions National Weather Service. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ Recurvature American Metereological Society. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ Glossary of NHC Terms. National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Chih-Pei Chang, East Asian Monsoon (Singapore: World Scientific, 2004, ISBN 9812387692).

- ↑ Hurricane Iris. Weather Underground. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ Addison Whipple, Storm (Alexandria, VA: Time Life Books, 1982, ISBN 0809443120).

- ↑ R. A. Scotti, Sudden Sea: the Great Hurricane of 1938 (Lebanon, IN: Little, Brown, and Company, 2003, ISBN 0316739111).

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 James M. Shultz, Jill Russell, and Zelde Espinel, Epidemiology of Tropical Cyclones: The Dynamics of Disaster, Disease, and Development. Epidemiologic Reviews 27(1) (July 2005): 21–35. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ Eastern Pacific Hurricane Season Outlook. Climate Prediction Center. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ Robert W. Christopherson, Geosystems: An Introduction to Physical Geography (New York, NY: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1992, ISBN 0023224436).

- ↑ The Hurricane Hunters. Hurricane Hunters Association. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ National Hurricane Center Forecast Verification. National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ Remy Melina, What's the Difference Between a Typhoon and a Super-Typhoon? Live Science, October 18, 2010. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ Dennis Mersereau, At 200 MPH, Hurricane Patricia Is Now the Strongest Tropical Cyclone Ever Recorded The Vane, October 23, 2015. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ Central Weather Bureau of the Ministry of Communications, 臺灣百年來之颱風. Government of the Republic of China. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ Douglas Harper, Typhoon. Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ Rachelle Oblack, Where Does the Word 'Hurricane' Come From? Thoughtco., October 17, 2019. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ Worldwide Tropical Cyclone Names National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 The world's deadliest hurricanes, typhoons and cyclones Deutsche Welle (DW). Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ The Deadliest Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, 1492-1996. National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ Worst Typhoons in the Philippines (1947 - 2009) Typhoon2000. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ Ray Sanchez and Greg Botelho, Hurricane Patricia weakens, but still 'extremely dangerous' CNN, October 23, 2015. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ Tiny Typhoon? NASA Earth Observatory. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ Jonathan Erdman, The Longest-Lasting, Farthest-Tracking Hurricanes on Record The Weather Channel, August 9, 2018. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ Christopher W. Landsea, Bruce A. Harper, Karl Hoarau, John A. Knaff, Can We Detect Trends in Extreme Tropical Cyclones? Science 313 (July, 2006):452-454. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Kerry Emanuel, Anthropogenic Effects on Tropical Cyclone Activity, July 2006. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ Kevin Trenberth, Rong Zhang, and National Center for Atmospheric Research Staff, Atlantic Multi-Decal Oscillation (AMO) Climate Data Guide, January, 2019. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ Kerry Emanuel, Increasing destructiveness of tropical cyclones over the past 30 years Nature 436(7051) (August 2005):686–688. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ P.J. Webster, G.J. Holland, J.A. Curry, and H.-R. Chang, Changes in Tropical Cyclone Number, Duration, and Intensity in a Warming Environment Science 309(5742) (2005):1844-1846. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Stefan Rahmstorf, Michael Mann, Rasmus Benestad, Gavin Schmidt, and William Connolley. Hurricanes and Global Warming - Is There a Connection? RealClimate, 2005. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory. Global Warming and Hurricanes. GFDL, June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ Christopher W. Landsea, Gabriel A. Vecchi, Lennart Bengtsson, and Thomas R. Knutson, Impact of Duration Thresholds on Atlantic Tropical Cyclone Counts J. Climate 23(10) (2010): 2508–2519. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ Mark A. Lander, N. Davidson, H. Rosendal, J. Knaff, and R. Edson, J. Evans, R. Hart. Fifth International Workshop on Tropical Cyclones NOAA, Mangilao, Guam. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ National Hurricane Center, Tropical Cyclone Naming History and Retired Names NOAA. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ↑ Mark Leberfinger and Ashley Williams, 1991 'Perfect Storm': How the deadly system that inspired a blockbuster hit took shape. AccuWeather. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ahrens, C. D. Meteorology: An Introduction to Weather, Climate, and the Environment. St. Paul, MN: West Publishing Company, 1994. ISBN 0534397751.

- Chang, Chih-Pei. East Asian Monsoon. Singapore: World Scientific, 2004. ISBN 9812387692.

- Christopherson, Robert W. Geosystems: An Introduction to Physical Geography. New York, NY: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1992. ISBN 0023224436.

- Hurricane Research Division. Hurricane Research Division: Frequently Asked Questions. Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, NOAA. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- Kochel, R. Craig, Victor R. Baker, and Peter C. Patton. Flood Geomorphology. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Interscience, 1988. ISBN 0471625582.

- Lutgens, F. K., and E. J. Tarbuck. The Atmosphere: An Introduction to Meteorology. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1998. ISBN 0131015672.

- Mann, M. E., and K. Emanuel. Atlantic Hurricane Trends Linked to Climate Change. EOS 87(24) (2006):233.

- Moran, J. M., and M. D. Morgan. Meteorology: The Atmosphere and the Science of Weather. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. 1997. ASIN B000O8WUGK

- Rahmstorf, Stefan, Michael Mann, Rasmus Benestad, Gavin Schmidt, and William Connolley. Hurricanes and Global Warming—Is There a Connection? RealClimate, September 2, 2005. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- Whipple, Addison. Storm. Alexandria, VA: Time Life Books, 1982. ISBN 0809443120.

External links

All links retrieved May 2, 2023.

- Frequently Asked Questions About Hurricanes NOAA.

- NOVA scienceNOW: Hurricanes.

- Mariner's Guide for Hurricane Awareness. PDF (1.23 MiB).

- World Meteorological Organization Severe Weather Information Center - Shows all current tropical systems worldwide and their tracks.

- US National Hurricane Center - North Atlantic, Eastern Pacific.

- Japan Meteorological Agency - NW Pacific.

- Météo-France - La Reunion - South Indian Ocean from Africa to 90° E.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.