Valerian

| Valerian | ||

|---|---|---|

| Emperor of the Roman Empire | ||

| ||

| Valerian on a coin celebrating goddess Fortuna | ||

| Reign | 253-260 (with Gallienus) | |

| Full name | Publius Licinius Valerianus (from birth to accession); Caesar Publius Licinius Valerianus Augustus (as emperor) | |

| Born | c. 200 | |

| Died | After 260 | |

| Bishapur | ||

| Predecessor | Aemilianus | |

| Successor | Gallienus (alone) | |

| Issue | Gallienus & Valerianus Minor | |

| Father | Senatorial | |

Publius Licinius Valerianus (c. 200 - after 260), commonly known in English as Valerian or Valerian I, was the Roman Emperor from 253 to 260. Valerian is mainly remembered for persecuting Christians and for the manner in which his life ended. He was captured and executed by the Persian King. In fact, he had made gains against Persia, restoring territory to Roman rule, until disease decimated the army. This period of Roman history saw rapid change of leadership, civil unrest, provinces splintering off from the center and rampant rivalry between men who set their sights on the throne. Emperors rarely had the opportunity to take the initiative; rather, they were compelled to respond to circumstances.

What Valerian failed to recognize was that the tide of history was running in Christianity's favor. Despite his persecutions and confiscations of Christian property, Christianity continued to grow. Few emperors at this time can be said to have controlled events; rather, they were controlled by events. Instead of persecuting Christians, it may have been more prudent for Valerian to ally himself with them. He does not appear to have especially disliked them. Perhaps the lesson that can be learned from his legacy is that he may have spent insufficient effort studying the times in which he lived. No ruler possesses a magical ability to discern where history is moving; on the other, even powerful men need to recognize currents against which they should not swim. Valerian missed an opportunity to align himself with the current of the times; that task fell to his successors.

Life

Origins and rise to power

Unlike the majority of the pretenders during the Crisis of the Third Century, Valerian was of a noble and traditional senatorial family.[1] He held a number of offices before he was named Emperor by the army, although details of his early life are elusive. He married Egnatia Mariniana, who gave him two sons: later emperor Publius Licinius Egnatius Gallienus and Valerianus Minor. In 238 he was princeps senatus, and Gordian I negotiated through him Senatorial recognition of his claim as emperor. In 251, when Decius revived the censorship with legislative and executive powers so extensive that it practically embraced the civil authority of the emperor, Valerian was chosen censor by the Senate, though he declined to accept the post.

Under Decius he was nominated governor of the Rhine provinces of Noricum and Raetia and retained the confidence of his successor, Trebonianus Gallus, who asked him for reinforcements to quell the rebellion of Aemilianus in 253. Valerian headed south, but was too late: Gallus' own troops had killed him and joined Aemilianus before his arrival. The Raetian soldiers then proclaimed Valerian emperor and continued their march towards Rome. At the time of his arrival in September, Aemilianus' legions defected, killing him and proclaiming Valerian emperor. In Rome, the Senate quickly acknowledged him, not only for fear of reprisals, but also because he was one of their own.

Rule

Valerian's first act as emperor was to make his son Gallienus his co-ruler. In the beginning of his reign affairs in Europe went from bad to worse and the whole of the West fell into disorder. The Rhine provinces were under attack from the Germanic tribes actually entering Italy, the first time that an invading army had done so since Hannibal. In the East, Antioch had fallen into the hands of a Sassanid vassal, Armenia was occupied by Shapur I (Sapor). Valerian and Gallienus split the problems of the empire between themselves, with the son taking the West and the father heading East to face the Persian threat.

The Valerian persecution

Valerian was not ill disposed towards Christians but is remembered by history for the "Valerian persecution." According to Löffler, he was manipulated by the ambitious general, Macrianus, to issue anti-Christian edicts calculated to create civil unrest from which Macrianus planned to benefit. Bunson says that he initiated persecution party to divert attention from his other problems and party to help himself to the not inconsiderable wealth of the Christian community.[2] In 257, Valerian forbade Christians from holding assemblies, entering subterranean places of burial, and sent clergy into exile.[3] The following year, an edict ordered instant death for anyone identified as a bishop, priest or deacon. If of Senatorial or knightly rank, they were first given the opportunity to recant and of proving their loyalty by sacrificing to the pagan gods. Christians in the "imperial household were sent in chains to perform forced labor." High ranking Christian women were banished. All property belonging to Christians was confiscated. During this persecution, the bishops of Rome, Pope Sixtus II, of Carthage, Cyprian and of Tarracona in Spain, Fructuosus lost their lives. Macrianus was himself killed in the unrest that did follow the persecutions as various rivals competed for power and the imperial throne. The special provision for Christians of high rank shows that at this period Christianity was no longer only attracting the poor but was also gaining converts from the highest ranks of society. Holloway comments that it was as a result of the Valerian persecution that Christian in high office "made their first concrete appearance as a group."[4] In fact, they continued to penetrate "further the upper ranks of society" until by the end of the century they were "prominent in the palace and in the army."[5]

Capture and Death

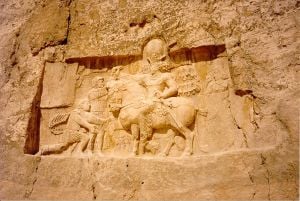

By 257, Valerian had recovered Antioch and had restored the province of Syria to Roman control but in the following year, the Goths ravaged Asia Minor. Later in 259, he moved to Edessa, but an outbreak of plague killed a critical number of legionaries, weakening the Roman position. Valerian was then forced to seek terms with Shapur I. Sometime towards the end of 259, or at the beginning of 260, Valerian was defeated in the Battle of Edessa and taken prisoner by the Persians. Valerian's capture was a humiliating defeat for the Romans.

Gibbon, in The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire describes Valerian's fate:

The voice of history, which is often little more than the organ of hatred or flattery, reproaches Sapor with a proud abuse of the rights of conquest. We are told that Valerian, in chains, but invested with the Imperial purple, was exposed to the multitude, a constant spectacle of fallen greatness; and that whenever the Persian monarch mounted on horseback, he placed his foot on the neck of a Roman emperor. Notwithstanding all the remonstrances of his allies, who repeatedly advised him to remember the vicissitudes of fortune, to dread the returning power of Rome, and to make his illustrious captive the pledge of peace, not the object of insult, Sapor still remained inflexible. When Valerian sunk under the weight of shame and grief, his skin, stuffed with straw, and formed into the likeness of a human figure, was preserved for ages in the most celebrated temple of Persia; a more real monument of triumph, than the fancied trophies of brass and marble so often erected by Roman vanity. The tale is moral and pathetic, but the truth of it may very fairly be called in question. The letters still extant from the princes of the East to Sapor are manifest forgeries; nor is it natural to suppose that a jealous monarch should, even in the person of a rival, thus publicly degrade the majesty of kings. Whatever treatment the unfortunate Valerian might experience in Persia, it is at least certain that the only emperor of Rome who had ever fallen into the hands of the enemy, languished away his life in hopeless captivity.[6]

Death in captivity

An early Christian source, Lactantius (c. 250 - c. 325), maintained that for some time prior to his death Valerian was subjected to the greatest insults by his captors, such as being used as a human footstool by Shapur I when mounting his horse. According to this version of events, after a long period of such treatment Valerian offered Shapur a huge ransom for his release. In reply, according to one version, Shapur was said to have forced Valerian to swallow molten gold (the other version of his death is almost the same but it says that Valerian was killed by being flayed alive) and then had the unfortunate Valerian skinned and his skin stuffed with straw and preserved as a trophy in the main Persian temple. It was further alleged by Lactantius that it was only after a later Persian defeat against Rome that his skin was given a cremation and burial. The role of a Chinese prince held hostage by Shapur I, in the events following the death of Valerian has been frequently debated by historians, without reaching any definitive conclusion.

It is generally supposed that some of Lactantius' account is motivated by his desire to establish that persecutors of the Christians died fitting deaths[7]the story was repeated then and later by authors in the Roman Near East "as a horror story" designed to depict the Persians as barbaric.[8]. According to these accounts, Valerian's skin was "stripped from his body, dyed a deep red and hung in a Persian temple" which visiting Roman envoys were subsequently "cajoled into entering." Meijer describes this as "the greatest indignity to which a Roman emperor has ever been subjected."[9] Isaac says that some sources have Valerian being flayed alive, some that he was "flayed after his death."[8]

Valerian and Gallienus' joint rule was threatened several times by usurpers. Despite several usurpation attempts, Gallienus secured the throne until his own assassination in 268. Among other acts, Gallienus restored the property of Christians confiscated during his father's reign.[5]

Owing to imperfect and often contradictory sources, the chronology and details of this reign are uncertain.

Family

- Gallienus

- Valerianus Minor was another son of Valerian I. He was probably killed by usurpers, some time between the capture of his father in 260 C.E. and the assassination of his brother Gallienus in 268.

Legacy

Constantine the Great would also divide the empire into East and West, founding the Byzantine Empire in the East, which survived until the Fall of Constantinople in 1453. Like Constantine, Valerian chose the East, not the West, as his own theater. Valerian may have contributed to the administrative structure of the empire. Valerian is remembered mainly for the persecution of Christians, for his capture and death. His reign took place during the period known as the "crises of the third century" (235-284) during which a total of 25 men ruled as emperors. During this period, the empire was plagued by rebellions, by the difficulty of governing the extensive imperial territory and by increasing civil unrest. This had a major economic impact because trade routes were often unsafe and communication suffered across the empire.

In many respects, Valerian was a capable ruler but he was also faced with serious problems, not least of all the very real possibility that the empire was disintegrating around him. Christians were seen as a source of disunity because they refused to honor the official cult. Rightly or wrongly, this was regarded as weakening the state. As distant provinces became unstable and increasingly isolated from the imperial center, "local gods became more attractive" which also weakened the imperial cult.[10] The imperial cult, centered on worship of the emperor, was designed to ensure that the loyalty and obedience of the emperor's subjects; could those who refused to worship him be trusted to serve and obey him? He does not appear to have been motivated by hatred for Christians. If he did want access to their wealth, this was probably in order to strengthen imperial power by using this to reward others for their loyalty.

When Constantine legalized Christianity, it was almost certainly because he thought it prudent to gain the support of an increasingly large community in his own battle for the throne. Constantine's successors set about making loyalty to the Christian church the test of loyalty to the state, simply substituting the new religion for the old imperial cult. Whether an emperor persecuted Christians or reversed the policy depended on what they believed was politically advantageous at the time. To a large degree, Valerian's actions were dictated by circumstances. Few emperors at this time can be said to have controlled events; rather, they were controlled by events. Valerian may actually have benefited more by allying himself with the increasingly large, wealthy and influential Christian community, as Constantine chose to do. Unlike Constantine, Valerian failed to recognize the direction in which history's current was flowing. Perhaps this is the lesson that can be learned from his legacy. On the one hand, no ruler possesses a magical ability to discern where history is moving; on the other, Valerian may have spent insufficient effort studying the times in which he lived. The fact that Christians included Senators and had enough property to make it worth Valerian's while to oppose them suggests that he might also have decided to enter an alliance with them.

|

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by: Aemilianus |

Roman Emperor 253–260 Served alongside: Gallienus |

Succeeded by: Gallienus |

Notes

- ↑ Valerian's full title was IMPERATOR CAESAR PVBLIVS LICINIVS VALERIANVS PIVS FELIX INVICTVS AVGVSTVS, "Emperor Caesar Publius Licinus Valerianus Pious Lucky Unconquered Augustus".

- ↑ Matthew Bunson. 1995. A dictionary of the Roman Empire. (New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195102338), 86.

- ↑ Klemens Löffler, Valerian. The Catholic Encyclopedia, 1912 ed., Vol. 15. (New York, NY: Robert Appleton Company). newadvent.org. Retrieved January 23, 2009.

- ↑ R. Ross Holloway. 2004. Constantine & Rome. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300100433), 11.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Holloway, 12.

- ↑ Edward Gibbon and J.B. Bury. 1914. The history of the decline and fall of the Roman empire. New York, (NY: Macmillan), 294.

- ↑ Fik Meijer. 2004. Emperors don't die in bed. (London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 9780415312011), 95.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Benjamin H. Isaac. 1998. The Near East under Roman rule: selected papers. (Mnemosyne, bibliotheca classica Batava, 177.)( Leiden, NL: Brill. ISBN 9789004107366), 440.

- ↑ Meijer, 96.

- ↑ Bunson, 1995, 204.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Aurelius, Victor, and Thomas M. Banchich, trans. 2000. Epitome de Caesaribus. New York, NY, Buffalo, NY: Canisius College. Retrieved January 23, 2009.

- Bunson, Matthew. 1995. A dictionary of the Roman Empire. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195102338.

- Eutropius, and John Selby Watson trans. 1853. Breviarium ab urbe condita London, UK: Henry G. Bohn. Retrieved January 23, 2009.

- Gibbon, Edward, and J.B. Bury. 1914. The history of the decline and fall of the Roman empire. New York, NY: Macmillan.

- Historia Augusta. 1932. The Two Valerians. Cambridge, UK: Loeb Classical Library. Retrieved January 23, 2009.

- Holloway, R. Ross. 2004. Constantine & Rome. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300100433.

- Isaac, Benjamin H. 1998. The Near East under Roman rule: selected papers. (Mnemosyne, bibliotheca classica Batava, 177.) Leiden, NL: Brill. ISBN 9789004107366.

- Lenski, Noel Emmanuel. 2006. The Cambridge companion to the Age of Constantine. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521818384.

- Lewis, Naphtali, and Meyer Reinhold. 1990. Roman civilization: selected readings. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231071307.

- Meijer, Fik. 2004. Emperors don't die in bed. London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 9780415312011.

- Southern, Pat. 2001. The Roman Empire from Severus to Constantine. London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 9780415239431.

- Zosimus. 1814. Historia Nova. (London, UK: Green and Chaplin). Retrieved January 23, 2009.

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

External links

All links retrieved May 3, 2023.

- "Valerian and Gallienus", at De Imperatoribus Romanis.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.