|

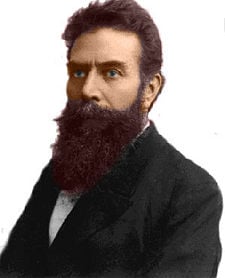

Wilhelm Röntgen | |

|---|---|

Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen | |

| Born |

March 27, 1845 |

| Died | February 10, 1923 Munich, Germany |

| Nationality | |

| Field | Physicist |

| Institutions | University of Strassburg Hohenheim University of Giessen University of Würzburg University of Munich |

| Alma mater | University of Utrecht University of Zürich |

| Known for | X-rays |

| Notable prizes | |

Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen (or William Conrad Roentgen, in English) (March 27, 1845 – February 10, 1923) was a German physicist of the University of Würzburg. On November 8, 1895, he produced and detected electromagnetic radiation in a wavelength range today known as X-rays or Röntgen Rays, an achievement that earned him the first Nobel Prize in Physics in 1901. He is also considered the father of Diagnostic Radiology, the medical field in which radiation is used to produce images to diagnose injury and disease.

Despite the fame he achieved for his discovery, Röntgen chose the path of humility. When others wished to name the new radiation after him, he indicated that he preferred the term X-rays. In addition, he declined most honors and speaking engagements that could have heightened his popularity. Rather than use his discovery to pursue personal wealth, he declared that he wanted his research to benefit humanity. Thus, he did not patent his discovery and donated his Nobel Prize money to his university for the advancement of scientific research.

Early life and education

Röntgen was born in Lennep (now a part of Remscheid), Germany, to a clothmaker. His family moved to Apeldoorn in the Netherlands when he was three years old. He received his early education at the Institute of Martinus Herman van Doorn. He later attended Utrecht Technical School, from which he was expelled for producing a caricature of one of the teachers, a "crime" he claimed not to have committed.

In 1865, he tried to attend the University of Utrecht without having the necessary credentials required for a regular student. Hearing that he could enter the Federal Polytechnic Institute in Zurich (today the ETH Zurich) by passing its examinations, he began studies there as a student of mechanical engineering. In 1869, he graduated with a Ph.D. from the University of Zurich.

Career

In 1867, Röntgen became a lecturer at Strasbourg University and in 1871 became a professor at the Academy of Agriculture at Hohenheim, Württemberg. In 1876, he returned to Strasbourg as a professor of Physics and in 1879, he was appointed to the Chair of physics at the University of Giessen. In 1888, he obtained the physics chair at the University of Würzburg, and in 1900 at the University of Munich, by special request of the Bavarian government. Röntgen had family in the United States (in Iowa) and at one time he planned to emigrate. Although he accepted an appointment at Columbia University in New York City and had actually purchased transatlantic tickets, the outbreak of World War I changed his plans and he remained in Munich for the rest of his career. Röntgen died in 1923 of carcinoma of the bowel. It is thought that his carcinoma was not a result of his work with ionizing radiation because his investigations were for only a short time and he was one of the few pioneers in the field who used protective lead shields routinely.

Discovery of X-rays

During 1895, Röntgen was using equipment developed by his colleagues (reputedly, Ivan Pulyui personally presented one (the 'Pulyui lamp') to Röntgen, but Röntgen went on to be credited as the major developer of the technology), Hertz, Hittorf, Crookes, Tesla, and Lenard to explore the effects of high tension electrical discharges in evacuated glass tubes. By late 1895 these investigators were beginning to explore the properties of cathode rays outside the tubes.

In early November of that year, Röntgen was repeating an experiment with one of Lenard's tubes in which a thin aluminum window had been added to permit the cathode rays to exit the tube but a cardboard covering was added to protect the aluminium from damage by the strong electrostatic field that is necessary to produce the cathode rays. He knew the cardboard covering prevented light from escaping, yet Röntgen observed that the invisible cathode rays caused a fluorescent effect on a small cardboard screen painted with barium platinocyanide when it was placed close to the aluminum window. It occurred to Röntgen that the Hittorf-Crookes tube, which had a much thicker glass wall than the Lenard tube, might also cause this fluorescent effect.

In the late afternoon of November 8, 1895, Röntgen determined to test his idea. He carefully constructed a black cardboard covering similar to the one he had used on the Lenard tube. He covered the Hittorf-Crookes tube with the cardboard and attached electrodes to a Ruhmkorff coil to generate an electrostatic charge. Before setting up the barium platinocyanide screen to test his idea, Röntgen darkened the room to test the opacity of his cardboard cover. As he passed the Ruhmkorff coil charge through the tube, he determined that the cover was light-tight and turned to prepare the next step of the experiment. It was at this point that Röntgen noticed a faint shimmering from a bench a meter away from the tube. To be sure, he tried several more discharges and saw the same shimmering each time. Striking a match, he discovered the shimmering had come from the location of the barium platinocyanide screen he intended to use next.

Röntgen speculated that a new kind of ray might be responsible. November 8 was a Friday, so he took advantage of the weekend to repeat his experiments and make his first notes. In the following weeks he ate and slept in his laboratory as he investigated many properties of the new rays he temporarily termed X-rays, using the mathematical designation for something unknown. Although the new rays would eventually come to bear his name when they became known as Röntgen Rays, he always preferred the term X-rays.

Röntgen's discovery of X-rays was not an accident, nor was he working alone. With the investigations he and his colleagues in various countries were pursuing, the discovery was imminent. In fact, X-rays were produced and a film image recorded at the University of Pennsylvania two years earlier. However, the investigators did not realize the significance of their discovery and filed their film for further reference, thereby losing the opportunity for recognition of one of the greatest physics discoveries of all time. The idea that Röntgen happened to notice the barium platinocyanide screen misrepresents his investigative powers; he had planned to use the screen in the next step of his experiment and would therefore have made the discovery a few moments later.

At one point, while he was investigating the ability of various materials to stop the rays, Röntgen brought a small piece of lead into position while a discharge was occurring. Röntgen thus saw the first radiographic image, his own flickering ghostly skeleton on the barium platinocyanide screen. He later reported that it was at this point that he determined to continue his experiments in secrecy, because he feared for his professional reputation if his observations were in error.

Röntgen's original paper, "On A New Kind Of X-Rays" (Über eine neue Art von Strahlen), was published 50 days later on December 28, 1895. On January 5, 1896, an Austrian newspaper reported Röntgen's discovery of a new type of radiation. Röntgen was awarded an honorary degree of Doctor of Medicine from University of Würzburg after his discovery. Although he was offered many other honors and invitations to speak and earn money by popularizing the phenomenon he had discovered, it was typical of his character that he declined most of these.

Röntgen's acceptance of the honorary title in Medicine indicated not only his loyalty to his University but also his clear understanding of the significance of his contribution to the improvement of medical science. He published a total of three papers on X-rays between 1895 and 1897. None of his conclusions have yet been proven false. Today, Röntgen is considered the father of Diagnostic Radiology, the medical specialty that uses imaging to diagnose injury and disease.

In 1901, Röntgen was awarded the very first Nobel Prize in Physics. The award was officially, "in recognition of the extraordinary services he has rendered by the discovery of the remarkable rays subsequently named after him". Röntgen donated the 50,000 Kroner prize money to his university for the purpose of scientific research. Professor Röntgen offered simple and modest remarks upon receiving the Nobel honor by promising, "...to continue scientific research that might be of benefit to humanity."[1] As Pierre Curie would do several years later, he refused to take out any patents related to his discovery on moral grounds. He did not even want the rays to be named after him.

Family data

- Spouse: Anna Bertha Ludwig (m. 1872, d. 1919)

- Children: Josephine Bertha Ludwig (adopted at age 6, in 1887, daughter of Anna's brother)

Awards and honors

- Nobel Prize in Physics (1901)

- Rumford Medal (1896)

- Matteucci Medal (1896)

- On November 2004, the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) named the element Roentgenium after him.

See also

- William Crookes

- Heinrich Hertz

- Nikola Tesla

- X-ray

Notes

- ↑ Bern Dibner, W.C. Rontgen and the Discovery of X-rays, Franklin Watts, Inc. 1968, p 77

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Dibner, Bern. 1968. Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen and the Discovery of X rays. Immortals of Science. New York, NY: Franklin Watts. OCLC 436057.

- Garcia, Kimberly. 2003. Wilhelm Roentgen and the Discovery of X-Rays. Unlocking the Secrets of Science. Bear, DE: Mitchell Lane Publishers. ISBN 1584151145.

- Glasser, Otto. 1934. Wilhelm Conrad Roentgen and the Early History of the Roentgen Rays. London: C.C. Thomas. ASIN B0006AMETE.

External links

All links retrieved May 5, 2023.

| ||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.