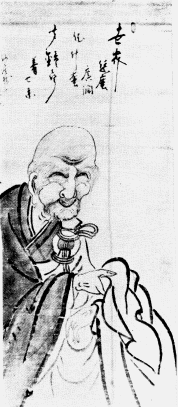

Yunmen Wenyan

| Yúnmén Wényǎn | |

|---|---|

| |

| Information | |

| Born: | 862 or 864 |

| Place of birth: | China |

| Died: | 949 |

| Nationality: | Chinese |

| School(s): | Ch'an |

| Title(s): | Ch'an-shih

|

Yúnmén Wényǎn (862 or 864[1] – 949 C.E.), (雲門文偃; Japanese: Ummon Bun'en; he is also variously known in English as "Unmon," "Ummon Daishi," "Ummon Zenji"), was a major[2] Chinese Chan master in Tang-era China. He founded one of the five major schools of Chan (Chinese Zen), the "Yunmen School," after succeeding his master, Xuefeng Yicun (or Hsueh-feng I-ts'un; Japanese: Seppo Gison; another disciple of Yicun would be Fa-yen Wen-i (885-958)[3]) (822-908), for whom he had served as a head monk. When founding his school, he taught at the Yunmen monastery of Shaozhou, from which he received his name. The Yunmen school flourished into the early Song Dynasty, with particular influence on the upper classes, and eventually culminating in the compilation and writing of the Hekiganroku. The school would eventually be absorbed by the Rinzai school later in the Song.[3]

Yunmen's Zen or Chan was known for its nobility. He required his disciples to strive for embodying Buddhist truth through excellence in character, realization, and practice. He is also known for expressing the entire Zen teachings in one word. Yunmen brought Zen to the next height by cultivating the truth embedded within Buddhism.

Biography

Yunmen was born in the town of Jiaxing near Suzhou and southwest of Shanghai to the Zhang family (but later as a monk he would take the name Wenyan; to avoid confusion he will be referred to by his later name of "Yunmen") probably in 864 C.E. His birth-year is uncertain; the two memorial stele at the Yunmen monastery mention he was 86 years old when he died in 949 C.E., which suggests that 864 is his birth year.

While a boy, Yunmen became a monk under a "commandment master" named Zhi Cheng[4] in Jiaxing. He studied there for several years, taking his monastic vows at age 20, in 883 C.E. The teachings there did not satisfy him, and he went to Daozong's school (also known as Bokushu, Reverend Chen, Muzhou Daozong, Ch'en Tsun-su, Mu-chou Tao-tsung, Tao-ming, Muzhou Daoming etc.[5]) to gain enlightenment and legendarily had his leg broken for his trouble. It was first said around 1100 that Yunmen was crippled in the leg:

Ummon Yunmen went to Bokushu's temple to seek Zen. The first time he went, he was not admitted. The second time he went, he was not admitted. The third time he went the gate was opened slightly by Bokushu, and thus Ummon stuck his leg in attempting to gain entrance. Bokushu urged him to "Speak! Speak!"; as Ummon opened his mouth, Bokushu pushed him out and slammed shut the large gate so swiftly that Ummon's leg was caught and was broken.

Daozong told Yunmen to visit the pre-eminent Chan master of the day,[5] Xuefeng Yicun of Mt. Hsiang-ku, in Fuzhou (Fukushū) in modern-day Fujian, and become his disciple, as Daozong was too old (~100 years old) to further teach Yunmen. After studying with him for several years, Yunmen received enlightenment. While Yunmen had received his teacher's seal and approval, he nevertheless did not become abbot, probably because his stay was only on the order of four or five years. When Yicun died, Yunmen began traveling and visited quite a number of monasteries, cementing his reputation as a Ch'an master.

During a subsequent visit to the tomb of the Sixth Patriarch in Guangdong, Yunmen ended up joining (c. 911 C.E.) the monastery of Rumin Chanshi/Ling-shu Ju-min, who died in 918 C.E.; the two of them became great friends. With his death, Yunmen became head priest of the Lingshu monastery on Mt. Lingshu (Reiju-in). In this Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms Period, the T'ang dynasty was greatly weakened, and entire sections of the empire had split away; the south was peaceful and developed, but the "North was torn by the ravages of war."[6] The area of Southern China where Yunmen lived broke free during the rebellion of Huang Chao, a viceroy of the Liu family. Eventually, the Liu family became the rulers of the Southern Han kingdom (918-978) during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms Period. The ruler, Liu Yan, visited the monastery for Rumin's cremation (as Liu often sought Rumin's advice), and met Yunmen.

Impressed, Liu Yan extended him his patronage and protection, as well as confirming his appointment as the new abbot of the Lingshu monastery. But Yunmen's fame drew a great flow of visitors from all over China and even from Korea. All these visitors proved too distracting for Yunmen's taste, and in 923, he asked the king (Liu Yan having died by this time[5] to aid him in building a new monastery on Mount Yunmen. The king acquiesced, and five years later, at the age of 64, Yunmen began living in and teaching in the monastery on the mountain from which he took the name. While the king and some of Yunmen's disciples continued to try to give Yunmen more responsibilities and honors, Yunmen refused, and returned to his monastery. This proved to be a wise decision, as his influence diminished considerably in succeeding years through palace intrigues and invasions.

One day, when Yunmen was 85 (or 86), he composed a farewell letter to his patron, the new king of the Southern Han, and gave a final lecture to his monks, finishing with the statement: "Coming and going is continuous. I must be on my way!" Then he (reputedly, in great pain because of his crippled leg) sat in a full lotus posture and died. He would be buried with great honors, and his surprisingly well-preserved corpse was exhumed several years later and given a procession. In honor of this, his monastery was given a new name, and two stele erected, which recorded his biography. Yunmen was succeeded as abbot by Dongshan Shouchu (Japanese: Tōzan Shusho; d. 900[7]). Suhotsu became abbot in 990 C.E.; although at the time, his foremost disciple was accounted Pai-yün Shih-hsing, who had founded his own temple on the nearby Mt. Pai-yün. His corpse would be venerated until the twentieth century, when it would disappear during the chaos of the Cultural Revolution.

Teachings

| How steep is Yün-mên's mountain! |

| How low the white clouds hang! |

| The mountain stream rushes so swiftly |

| That fish cannot venture to stay. |

| One's coming is well-understood |

| From the moment one steps in the door. |

| Why should I speak of the dust |

| On the track that is worn by the wheel? |

| —Yun-men, from the Jingde Chuandeng Lu 《景德傳燈錄》 |

- "Ummon's school is deep and difficult to understand since its mode of expression is indirect; while it talks about the south, it is looking at the north."—Gyomay Kubose

Yunmen was renowned for his forceful and direct yet subtle teaching, often expressed through sudden shouts and blows with a staff, and for his wisdom and skill at oratory: he was "the most eloquent of the Ch'an masters."[8] Fittingly, Yunmen is one of the greatest pioneers of "live words," "old cases," and paradoxical statements that would later evolve into the koan tradition, along with Zhaozhou (Japanese: Jōshū Jūshin). He also famously specialized in apparently meaningless short sharp single word answers, like "Guan!" (literally, "barrier" or "frontier pass")—these were called "Yunmen's One Word Barriers." These one-word barriers "...were meant to aid practice, to spur insight, and thus to promote realization. Not only his punchy one-syllable retorts, but also his more extended conversation and stories came to be used as koan."[7] While his short ones were popular, some of his longer ones were iconic and among the most famous koans:

- Yun-men addressed the assembly and said: "I am not asking you about the days before the fifteenth of the month. But what about after the fifteenth? Come and give me a word about those days."

- And he himself gave the answer for them: "Every day is a good day."[9]

Most were collected in the Yúnmén kuāngzhēn chánshī guǎnglù (雲門匡眞禪師廣錄). But not all were—18 were later discovered when a subsequent master of the Yunmen school, one Xuetou Chongxian (Setchō Jūken, 980-1052 C.E.) published his Boze songgu, which contained one hundred "old cases" (as koans were sometimes called) popular in his teaching line, in which the 18 Yunmen koans were included. Of the many stories and koans in Blue Cliff Records, 18 involve Yunmen; eight of Yunmen's sayings are included in Records of Serenity, and five in The Gateless Gate; further examples could be found in the Ninden gammoku,[10] and the Ummonroku.[11] He was also considerably more mystical than certain other teachers who tended to concrete description; an apocryphal anecdote that began circulating around the beginning of the 1100s has Yunmen going so far as to forbid any of his sayings or teachings from being recorded by his many pupils ("What is the good of recording my words and tying up your tongues?" was one of his sayings):

- Chan Master Yunju of Foyin had said:

- "When Master Yunmen expounded the Dharma he was like a cloud. He decidedly did not like people to note down his words. Whenever he saw someone doing this he scolded him and chased him out of the hall with the words, "Because your own mouth is not good for anything you come to note down my words. It is certain that some day you'll sell me!""

- As to the records of "Corresponding to the Occasion" (the first chapter of The Record of Yunmen) and "Inside the Master's Room" (the first section of the second chapter of The Record of Yunmen): Xianglin and Mingjiao had fashioned robes out of paper and wrote down immediately whenever they heard them.

His disciples reputedly numbered 790, an unusual number of whom became enlightened. These successors would spread the Yunmen school widely; it flourished as one of the Five Schools for about 300 years, after which it was absorbed into the Linji School towards the end of the Southern Song dynasty (~1127 C.E.).

See also

Notes

- ↑ Dumoulin (1994), 230.

- ↑ "Yun-men Wen-yen (864-949) was one of the most eminent Zen personalities of his time." Dumoulin (1994), 230.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Dumoulin, p. 233.

- ↑ Isshuu Miura and Ruth Fuller Sasaki, Zen Dust: The History of the Koan and Koan Study in Rinsai (Lin-Chi) Zen. As Miura and Sasaki describe it, which usually refers to a specialist in vinaya: monastic rules and discipline; Sørensen mentions that some sources say that Chih-Ch'eng/Zhi Cheng was actually a Ch'an master

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Dumoulin (1994), 231.

- ↑ Dumoulin, p. 230.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Dumoulin, p. 232.

- ↑ Jingxiong Wu (1996), 213.

- ↑ See K. Sekida, Two Zen Classics, p. 161; Dumoulin (1994), 232.

- ↑ Chinese: Jen-t'ien yen-mu, compiled by Hui-yen Chih-chao, a Lin-chi monk. He wrote a history of the Five Houses of Zen Buddhism: Yun-men, Ts'ao-tung, Kuei-yan, and Fa-yen, as well as his own, Lin-chi. See Dumoulin (1994), 214.

- ↑ Ummon Kyōshin zenji kōroku; Chinese: Yün-men K'uang-chen ch'an-shih kuang-lu; shorter: Ummon Ōsho kōroku. The most common abbreviation is just Ummonroku (Chinese: Yün-men lu), though. It was first published in three books in 1076. See Dumoulin (1994), 241.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Daoyuan, Shi and Zhongyuan Zhang. 1971. Original teachings of Ch'an Buddhism: selected from The transmission of the lamp. New York, Toronto: Random House. ISBN 0-394-71333-8

- Dumoulin, Heinrich. 1994. Zen Buddhism: a history. Vol.1, , India and China,: with a new supplement on the Northern School of Chinese Zen. Nanzan studies in religion and culture. New York: Simon & Schuster Macmillan. ISBN 0-02-897109-4

- Kubose, Gyomay M. 1973. Zen Koans. Chicago: H. Regnery. ISBN 978-0809290659 ISBN 0-8092-9065-0

- Miura, Isshū, and Ruth Fuller Sasaki. 1967. Zen dust; the history of the koan and koan study in Rinzai (Lin-chi) Zen. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World.

- Sekida, Kazuki, A. V. Grimstone, Huikai, and Yuanwu. 2005. Two Zen classics: the Gateless gate and the Blue cliff records. Boston, Mass: Shambhala. ISBN 9781590302828

- Sørensen, Henrik Hjort. 1996. "The Life and Times of the Ch'an Master Yūn-men Wen-yan." Acta orientalia, pp. 105-131, Vol. 49.

- Wu, Jingxiong. 1996. The golden age of Zen. New York: Image. ISBN 9780385479936

- Yamada, Kōun, and Huikai. 1990. Gateless Gate. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1990. ISBN 9780816512164

- Yuanwu, Thomas F. Cleary, and J.C. Cleary. 1977. The Blue Cliff Record. Boulder, Colo: Shambhala, 1977. ISBN 9780877730941

External links

All links retrieved June 7, 2023.

- Zen Buddhism: An Introduction to Zen with Stories and Parables

- Ummon

- Transcription online of Pen-chi of Ts'ao-shan's Questions and Answers, as translated in Sources of Chinese Tradition (de Bary, Chan and Watson, ed. and trans.)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.