Raja yoga

RÄja Yoga ("Royal yoga," "Royal Union," also known as Classical Yoga or simply Yoga) is one of the six orthodox (astika) schools of Hindu philosophy, outlined by Patanjali in his Yoga Sutras. It is also sometimes referred to as Aá¹£á¹Änga (eight-limbed) yoga because there are eight integral practices on its yogic path. Raja yoga is concerned principally with the cultivation of the mind using meditation (dhyana) to control and subdue mental fluctuations in order to still the mind and achieve liberation.

RÄja Yoga seeks to discipline and calm one's body and thoughts so that their true spiritual nature will shine forth. By learning to control the universe of one's own mind, it is said that a yogi (practitioner of yoga) can attain spiritual liberation (enlightenment).

Etymology

The term Raja Yoga derives from two Sanskrit words "Raja" ("King") and "Yoga" (from the root Yuj meaning "to control"). Thus, placed together, the term "Raja Yoga" means the "Royal Yoga," the "King of the Yogas," the "Highest Yoga," the "Regal way of controlling one's mind and thoughts."

The word was first used in connection with harnessing animals (controlling them with leashes). Out of this literal practice arose the metaphorical idea of harnessing the thoughts of the mind through mental discipline, which became the practice of yoga.

History

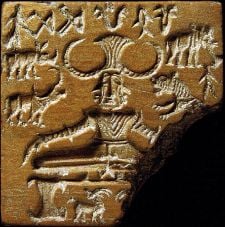

Archaeological excavations of the Indus Valley Civilization have unearthed a figure who appears to be practicing meditation or yoga; however, this interpretation is merely a conjecture.

The earliest written accounts of yoga appear in the Rig Veda, which began to be codified between 1500 and 1200 B.C.E. In the Upanishads, the older Vedic practices of offering sacrifices and ceremonies to appease external gods gave way instead to a new understanding that humans can, by means of an inner sacrifice, become one with the Supreme Being (referred to as BrÄhman or MÄhÄtman), through moral culture, restraint and training of the mind.

The Bhagavad Gita (written between the fifth and second centuries B.C.E.) defines yoga as the highest state of enlightenment attainable, beyond which there is nothing worth realizing, in which a person is never shaken, even by the greatest pain. [1] In his conversation with Arjuna, Krishna distinguishes several types of "yoga," corresponding to the duties of different nature of people:

- (1) Karma yoga, the yoga of "action" in the world.

- (2) Jnana yoga, the yoga of knowledge and intellectual endeavor.

- (3) Bhakti yoga, the yoga of devotion to a deity (for example, to Krishna).

Patanjali

Authorship of the Yoga Sutras, which form the basis of the darshana called "yoga," is attributed to Patanjali (second century B.C.E.). atañjali (DevanÄgarÄ« पतà¤à¥à¤à¤²à¤¿) is known as the compiler of the Yoga Sutras, a major work containing aphorisms on the philosophical aspects of mind and consciousness, and is therefore traditionally regarded as the âfounderâ of the Yoga school. An individual named Patañjali, who was born in Gonarda and lived, for at least some period, in Kashmir around 140 B.C.E., wrote MahÄbhÄá¹£ya, or Great Commentary, on the Aá¹£á¹ÄdhyÄyÄ« of the early Sanskrit grammarian PÄá¹ini. Many scholars do not consider these two texts to have been written by the same individual, although a comparative study of the two works produces no conclusive evidence. Two eighteenth-century Indian commentators, RhÄmabadra Diksita (author of Patanjalicarita) and Sivrama, and two eleventh-century commentators, King Bhoja of DhÄr and CakrapÄnidatta, identified the authors of the two works as being the same person.[2]Modern scholarship suggests that the two works may have been written several centuries apart.[3]

Yoga Sutras

The Yoga SÅ«tras probably date from around 250 - 200 B.C.E., though some scholars have based a later date of 250 C.E. on the fact that no commentaries on the Yoga Sutras exist before this date. The first three books appear to have been written much earlier than the fourth, which contains material that seems to refer to late Buddhist thought and could therefore place it in the fifth century C.E..[4]

Patañjali has often been called the founder of Yoga because of the Yoga Sūtras, although it was actually a compilation of a much older oral tradition. The Yoga Sūtras, as a treatise on Yoga, built on the Samkhya school and the Hindu scripture of the Bhagavad Gita (see also: Vyasa). Yoga, the science of uniting one's consciousness, is also found in the Puranas, the Vedas and the Upanishads. Patañjali reinterpreted and clarified what others had said, resolved contradictions, and synthesized many lines of argument. His practical summary can be regarded the greatest initiator into the essence and the science of Yoga.

Yoga SÅ«tras is a major work among the great Hindu scriptures and serves as the basis of the yoga-system known as Raja yoga. Patañjali's Yoga is one of the six schools or darshanas of Hindu Philosophy. The sÅ«tras give us the earliest reference to the popular term Ashtanga Yoga which translates literally as the âeight limbs of yoga.â They are yama, niyama, asana, pranayama, pratyahara, dharana, dhyana and samadhi.

The Yoga SÅ«tras is to be regarded as a devotional handbook rather than a philosophical text to be studied as an end in itself. Patanjali himself repeatedly warns against the futility of approaching meditation through the intellect, emphasizing the attainment of wisdom which lies beyond intellect by abandoning conceptual frameworks. The sutras can be understood more deeply in the context of the readerâs own direct meditative experiences.

According to biographer and scholar Kofi Busia, Patañjali defended several ideas in his treatise on yoga that are not in accord with classical Sankhya or Yoga. He does not acknowledge the ego as a separate entity, and does not regard the subtle body linga sarira as permanent, denying it a direct control over external matters.[3]

The Yoga Sutra is divided into four parts: The first, Samahdi-pada, deals with the nature and aim of concentration. The second, Sadhanapada explains the means to realize this concentration. The third, Vibhuitpada, deals with the supranormal powers which can be acquired through yoga, and the fourth, Kaivalyapada, describes the nature of liberation and the reality of the transcendental self.[3]

Philosophy

The Yoga system one of the six "orthodox" Vedic schools of Hindu philosophy. The school (darshana) of Yoga is primarily Upanishadic with roots in Samkhya, and some scholars see some influence from Buddhism. The Yoga system accepts Samkhya psychology and metaphysics, but is more theistic and adds God to the Samkhyaâs twenty-five elements of reality[5] as the highest Self distinct from other selves.[1] Ishvara ( the Supreme Lord) is regarded as a special Purusha, who is beyond sorrow and the law of Karma. He is one, perfect, infinite, omniscient, omnipresent, omnipotent and eternal. He is beyond the three qualities of Sattva, Rajas and Tamas. He is different from an ordinary liberated spirit, because Ishvara has never been in bondage.

Patanjali was more interested in the attainment of enlightenment through physical activity than in metaphysical theory. Samkhya represents knowledge, or theory, and Yoga represents practice.

The goal of Yoga is defined as 'the cessation of mental fluctuations' (cittavrtti nirodha). Chitta (mind-stuff) is the same as the three âinternal organsâ of Samkhya: intellect (buddhi), ego (anhakara) and mind (manas). Chitta is the first evolute of praktri (matter) and is in itself unconscious. However, being nearest to the purusa (soul) it has the capacity to reflect the purusa and therefore appear conscious. Whenever chitta relates to or associates itself with an object, it assumes the form of that object. Purusa is essentially pure consciousness, free from the limitations of praktri (matter), but it erroneously identifies itself with chitta and therefore appears to be changing and fluctuating. When purusa recognizes that it is completely isolated and is a passive spectator, beyond the influences of praktri, it ceases to identify itself with the chitta, and all the modifications of the chitta fall away and disappear. The cessation of all the modifications of the chitta through meditation is called âYoga.â[1]

The reflection of the purusa in the chitta, is the phenomenal ego (jiva) which is subject to birth, death, transmigration, and pleasurable and painful experiences; and which imagines itself to be an agent or enjoyer. It is subject to five kinds of suffering: ignorance (avidyÄ), egoism (asmitÄ), attachment (rÄga), aversion (dveÅa), and attachment to life coupled with fear of death (abhinivesha).

Goal

The ultimate goal of yoga is clearly announced in the opening verse of Patanjali's Yoga Sutra, which states: yogaÅ citta-vá¹tti-nirodhaḥ (1.2), "Yoga limits the oscillations of the mind." They go on to detail the ways in which mind can create false ideations and advocate meditation on real objects, which process, it is said, will lead to a spontaneous state of quiet mind, the "Nirbija" or "seedless state," in which there is no mental object of focus.

Practices that serve to maintain for the individual the ability to access this state may be considered Raja Yoga practices. Thus, Raja Yoga encompasses and differentiates itself from other forms of Yoga by encouraging the mind to avoid the sort of absorption in obsessional practice (including other traditional yogic practices) that can create false mental objects.

In this sense, Raja Yoga is "king of yogas": all yogic practices are seen as potential tools for obtaining the seedless state, itself considered to be the starting point in the quest to cleanse Karma and obtain Moksha or Nirvana. Historically, schools of yoga that label themselves "Raja" offer students a mix of yogic practices and (hopefully or ideally) this philosophical viewpoint. He states that the purpose of Yoga is the cessation of mental fluctuations, with the implied goal of stilling the mind in order to discover and see one's true self and nature. This true Self is described as pure Spirit (Purusha). As stated earlier, Raja Yoga is predicated on Samkhian metaphysics and thus assimilated the concepts of Purusha and Prakriti found in Samkhya thought. As a result, Raja Yoga teaches that the ultimate goal of yoga is to realize that one is pure spirit and not matter, which is attained through discriminating knowledge (viveka of the real from the unreal.

Practice

Patanjala Yoga is also known as Raja Yoga (Sanskrit: "Royal yoga") or "Ashtanga Yoga" ("Eight-Limbed Yoga"), and is held as authoritative by all schools.

Raja Yoga aims at controlling all thought-waves or mental modifications. Raja Yoga is so-called because it is primarily concerned with the mind, which is traditionally conceived as the "king" of the psycho-physical structure that does its bidding. Because of the relationship between the mind and the body, the body must be first "tamed" through self-discipline and purified by various means. A good level of overall health and psychological integration must be attained before the deeper aspects of yoga can be pursued. Humans have all sorts of addictions and obsessions and these preclude the attainment of tranquil abiding (meditation). Through restraint (yama) such as celibacy, abstaining from drugs and alcohol, and careful attention to one's actions of body, speech and mind, the human being becomes fit to practice meditation. This yoke that one puts upon oneself (discipline) is another meaning of the word yoga.

Eight limbs of Raja/Ashtanga Yoga

The eight limbs of Raja/Ashtanga Yoga are:

- Yama - Code of conduct - self-restraint

- Niyama - religious observances - commitments to practice, such as study and devotion

- Äsana - integration of mind and body through physical activity

- Pranayama - regulation of breath leading to integration of mind and body

- Pratyahara - abstraction of the senses, withdrawal of the senses of perception from their objects

- Dharana - concentration, one-pointedness of mind

- Dhyana - meditation (quiet activity that leads to samadhi)

- Samadhi - the quiet state of blissful awareness, superconscious state

Yama

Yama ("abstentions") refers to five prohibited activities for the yoga practicioner: they must avoid hurting others through thought, word or deed (ahimsa); avoid falsehood (satya); avoid stealing (asteya); avoid passions and lust (brahmacharya); and avoid avarice (aparigraha). Put in another way, Yama involves Ahimsa (non-violence), Satya (truthfulness), Asteya (not stealing), Brahmacharya (celibacy), and Aparigraha (non-covetousness).

Niyama

Niyama ("observances") involves five practices that a yoga practicioner should actively cultivate: 1) external and internal purification (shaucha), 2) contentment (santosa), 3) austerity (tapas), 4) study (svadhyaya), and 5) surrender to God (Ishvara-pranidhana). It is said that a person who practises meditation without ethical perfection, without the practice of Yama-Niyama cannot obtain the fruits of meditation. One must purify one's mind first to practice regular meditation.

Asana

Asana (Sanskrit: "Seat" or "seal") refers to various body postures that are practiced for disciplining the senses. This term literally means "seat," and originally referred mainly to seated positions. With the rise of Hatha yoga, it came to be used for yoga "postures" as well.

Pranayama

Pranayama ("breath-control") checks the outgoing tendencies of the mind. Prana means life force, while yama means to gain control. Control of prÄna or vital breath.

Pratyahara

Pratyahara ("Abstraction") gives inner spiritual strength. It removes all sorts of distractions. It develops will-power. Vyasa describes it as that by which the senses do not come into contact with their objects and, as it were, follow the nature of the mind.

Dharana

Dharana ("Concentration") involves fixing one's attention on a single object. Concentration is a preliminary step to meditation. At this level, the yogi focuses on retention of breath, Brahmacharya, Satvic (pure) food, seclusion, silence, Satsanga (being in the company of a guru), and not mixing much with people are all aids to concentration. Concentrate on Trikuti (the space between the two eyebrows) with closed eyes is preferred. The mind can be easily controlled, as this is the seat for the mind.

Dhyana

Dhyana ("Meditation") The undisturbed flow of thought around the object of meditation. The mind passes into many conditions or states as it is made up of three qualities-Sattva, Rajas and Tamas. Kshipta (wandering), Vikshipta (gathering), Mudha (ignorant), Ekagra (one-pointed), and Nirodha (contrary) are the five states of the mind. Control the mind by Abhyasa (practice) and Vairagya (dispassion). Any practice which steadies the mind and makes it one-pointed is Abhyasa. Dull Vairagya will not help a person in attaining perfection in Yoga. One must have Para Vairagya or Theevra Vairagya, intense dispassion.

Samadhi

Samadhi: âConcentration.â Super-conscious state or trance (state of liberation) in which the mind is completely absorbed in the object of meditation. Samadhi is of two kinds: 1) Savikalpa, Samprajnata or Sabija; and 2) Nirvikalpa, Asamprajnata or Nirbija. In Savikalpa or Sabija, there is Triputi or the triad (knower, known and knowledge). The samskaras are not burnt or freed. Savitarka, Nirvitarka, Savichara, Nirvichara, Sasmita and Saananda are the different forms of Savikalpa Samadhi. In Nirbija Samadhi or Asamprajnata Samadhi there is no triad.

A Raja Yogi practices Samyama or the combined practice of Dharana, Dhyana and Samadhi at one and the same time and gets detailed knowledge of an object.

Misconceptions

In western popular culture and yoga classes, it is sometimes said that the goal of Yoga is to "unite with God." However, according to the ancient texts, this view of Yoga is misleading. The ultimate goal of yoga is clearly announced in the opening verse of Patanjali's Yoga Sutra, which states: yogaÅ citta-vá¹tti-nirodhaḥ, meaning that Yoga seeks the cessation of mental fluctuations (cittavrtti nirodha) in order to discriminate between the real and the unreal. Since the Raja Yoga system adopts Samkhyan metaphysics, the real is postulated as purusha (Cosmic spirit). Thus, while the concept of a personal God can play a role in helping the aspirant attain greater concentration in yogic practice (as a meditative focus), the ultimate realization of differentiation between Purusha and Prakriti is not necessarily the same thing as union with God, as traditionally understood by Westerners. Nevertheless, the intrinsic metaphysical diversity of Hinduism has allowed yogic practitioners to interpret ancient teachings in a variety of ways to suit their own interests as yoga has adapted to modern times and non-Indian societies.

Notes

- â 1.0 1.1 1.2 Chandrahar Sharma, A Critical Survey of Indian Philosophy (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 2003, ISBN 8120803647).

- â Surendranath Dasgupta, A History of Indian Philosophy, Vol. I (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1973, ISBN 8120804120), 230-232.

- â 3.0 3.1 3.2 Kofi Busia, Biography of Patanjali. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- â Heinrich Robert Zimmer, Philosophies of India (Bollingen series, 26. New York: Pantheon Books, 1951), 282-283.

- â Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan and Charles A. Moore (eds.), A Sourcebook in Indian Philosophy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1973, ISBN 0691019584), 453.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Dasgupta, Surendranath. 1973. A History of Indian Philosophy, Vol. I. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 8120804120

- Patañjali, & B. S. Miller, (1996). Yoga discipline of freedom: the Yoga Sutra attributed to Patanjali ; a translation of the text, with commentary, introduction, and glossary of keywords. Berkeley, Calif: University of California Press. ISBN 0520201906

- Patanjali, and B. K. S. Iyengar. 2002. Light on the yoga sutras of Patanjali. London: Thorsons. ISBN 0007145160

- Radhakrishnan, Sarvepalli and Moore, Charles A., eds. A Sourcebook in Indian Philosophy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1973. ISBN 0691019584

- Sharma, Chandrahar. 2003. A Critical Survey of Indian Philosophy. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 8120803647

- Sivananda, Swami. Raja Yoga. reprint ed. Kessinger Publishing, 2005. ISBN 978-1425359829

- Thakar, Vimala. Glimpses of Raja Yoga: An Introduction to Patanjali's Yoga Sutras (Yoga Wisdom Classics). Rodmell Press; 1st North American Pbk. Ed edition, 2004. ISBN 978-1930485075

- Villoldo, Alberto. 2007. Yoga, power, and spirit Patanjali the Shaman. Carlsbad, Calif: Hay House, Inc. ISBN 9781401910471

- Vivekananda,Swami. Raja-Yoga. Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center; Pocket Rev edition (June 1980. ISBN 978-0911206234

- Zimmer, Heinrich Robert. 1951. Philosophies of India. Bollingen series, 26. [New York]: Pantheon Books.

External links

All links retrieved December 7, 2022.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Raja_Yoga history

- Yoga history

- History_of_Yoga history

- Buddhism_and_Hinduism history

- Patanjali history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.