Difference between revisions of "Massachusetts Institute of Technology" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 153: | Line 153: | ||

Many MIT students also engage in "hacking," which encompasses both the [[Roof and tunnel hacking|physical exploration of areas]] that are generally off-limits (such as rooftops and steam tunnels), as well as [[hack (practical joke)|elaborate practical jokes]]. Recent hacks have included the theft of Caltech's cannon,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.mitcannon.com/ |title=Howe & Ser Moving Co. |accessdate=2007-04-04}}</ref> reconstructing a [[Wright Flyer]] atop the Great Dome,<ref>{{cite news|title=Mit Pranksters Wing It For Wright Celebration |publisher=Boston Globe |date=December 18, 2003 |author=MARCELLA BOMBARDIERI |url=http://nl.newsbank.com/cgi-bin/ngate/BG?ext_docid=0FF8A4DEBA245CA5&ext_hed=MIT%20PRANKSTERS%20WING%20IT%20FOR%20WRIGHT%20CELEBRATION&ext_theme=bg&pubcode=BG}}</ref> and adorning the [[John Harvard (clergyman)|John Harvard]] statue with the [[Master Chief (Halo)|Master Chief's Spartan Helmet]].<ref>{{cite web|title=MIT Hackers & Halo 3 |publisher=The Tech |url=http://www-tech.mit.edu/V127/N41/graphics/halo3.html |accessdate=2007-09-25}}</ref> | Many MIT students also engage in "hacking," which encompasses both the [[Roof and tunnel hacking|physical exploration of areas]] that are generally off-limits (such as rooftops and steam tunnels), as well as [[hack (practical joke)|elaborate practical jokes]]. Recent hacks have included the theft of Caltech's cannon,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.mitcannon.com/ |title=Howe & Ser Moving Co. |accessdate=2007-04-04}}</ref> reconstructing a [[Wright Flyer]] atop the Great Dome,<ref>{{cite news|title=Mit Pranksters Wing It For Wright Celebration |publisher=Boston Globe |date=December 18, 2003 |author=MARCELLA BOMBARDIERI |url=http://nl.newsbank.com/cgi-bin/ngate/BG?ext_docid=0FF8A4DEBA245CA5&ext_hed=MIT%20PRANKSTERS%20WING%20IT%20FOR%20WRIGHT%20CELEBRATION&ext_theme=bg&pubcode=BG}}</ref> and adorning the [[John Harvard (clergyman)|John Harvard]] statue with the [[Master Chief (Halo)|Master Chief's Spartan Helmet]].<ref>{{cite web|title=MIT Hackers & Halo 3 |publisher=The Tech |url=http://www-tech.mit.edu/V127/N41/graphics/halo3.html |accessdate=2007-09-25}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The MIT Blackjack Team was a group of students and ex-students from MIT but also including several from [[Harvard University]], who utilized [[card-counting]] techniques and more sophisticated strategies to beat [[casino]]s at [[blackjack]]. The team and its successors operated from 1979 through the beginning of the twentyfirst century. The origin of blackjack play at MIT was a mini-course called 'How to Gamble if You Must', taught in January 1979 at MIT over what is known as Independent Activities Period (IAP). A number of MIT students from living groups in the Burton House dorm known as Burton V and Conner III, who often played penny-ante [[poker]] with each other, attended this course and learned about blackjack and card counting methods. They then tried out their techniques in casinos in [[Atlantic City]]. Despite initial failures, two of them continued the course and, with the help of a Harvard graduate, formed a professional team who went on to make a fortune in [[Las Vegas]]. Stories, some true and some fictionalized, about a few of the players from the MIT Blackjack Team formed the basis of the ''[[New York Times]]'' bestsellers, ''Bringing Down the House'' and ''Busting Vegas'', written by [[Ben Mezrich]]. | ||

===Athletics=== | ===Athletics=== | ||

Revision as of 19:00, 6 May 2008

| |

| Motto | "Mens et Manus" (Latin for "Mind and Hand") |

|---|---|

| Established | 1861 (opened 1865) |

| Type | Private |

| Location | Cambridge, Mass. USA |

| Website | web.mit.edu |

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private, coeducational research university located in Cambridge, Massachusetts. MIT has five schools and one college, containing 32 academic departments, with a strong emphasis on scientific and technological research. MIT is one of two private land-grant universities as well as a sea-grant and space-grant university.

MIT is one of the foremost centers of science in the United States and the world, producing leaders in all aspects of science and technology with strong relationships in academia, government, and industry.

Mission and reputation

MIT was founded by William Barton Rogers in 1861 in response to the increasing industrialization of the United States. Although based upon German and French polytechnic models of an institute of technology, MIT's founding philosophy of "learning by doing" made it an early pioneer in the use of laboratory instruction,[1] undergraduate research, and progressive architectural styles. As a federally funded research and development center during World War II, MIT scientists developed defense-related technologies that would later become integral to computers, radar, and inertial guidance. After the war, MIT's reputation expanded beyond its core competencies in science and engineering into the social sciences including economics, linguistics, political science, and management. MIT's endowment and annual research expenditures are among the largest of any American university.[2]

MIT graduates and faculty are noted for their technical acumen (64 Nobel Laureates, 47 National Medal of Science recipients, and 29 MacArthur Fellows),[3][4] entrepreneurial spirit (a 1997 report claimed that the aggregated revenues of companies founded by MIT affiliates would make it the twenty-fourth largest economy in the world),[5] and irreverence (the popular practice of constructing elaborate pranks, or hacking, often has anti-authoritarian overtones).

History

Founding

In 1861, The Commonwealth of Massachusetts approved a charter for the incorporation of the "Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Boston Society of Natural History" submitted by William Barton Rogers. Rogers sought to establish a new form of higher education to address the challenges posed by rapid advances in science and technology during the mid-19th century with which classic institutions were ill-prepared to deal.[6] The Rogers Plan, as it came to be known, was rooted in three principles: the educational value of useful knowledge, the necessity of “learning by doing,” and integrating a professional and liberal arts education at the undergraduate level.[7][8]

Because open conflict in the Civil War broke out only a few months later, MIT's first classes were held in rented space at the Mercantile Building in downtown Boston in 1865.[9] Construction of the first MIT buildings was completed in Boston's Back Bay in 1866 and MIT would be known as "Boston Tech." During the next half-century, the focus of the science and engineering curriculum drifted towards vocational concerns instead of theoretical programs. Charles William Eliot, the president of Harvard University, repeatedly attempted to merge MIT with Harvard's Lawrence Scientific School over his 30-year tenure: overtures were made as early as 1869[10] with other proposals in 1900 and 1914 ultimately being defeated.[11][12][13][14]

Expansion

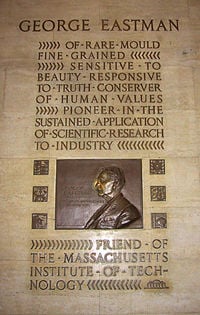

The attempted mergers occurred in parallel with MIT's continued expansion beyond the classroom and laboratory space permitted by its Boston campus. President Richard Maclaurin sought to move the campus to a new location when he took office in 1909.[15] An anonymous donor, later revealed to be George Eastman, donated the funds to build a new campus along a mile-long tract of swamp and industrial land on the Cambridge side of the Charles River. In 1916, MIT moved into its handsome new neoclassical campus designed by the noted architect William W. Bosworth which it occupies to this date. The new campus triggered some changes in the stagnating undergraduate curriculum, but in the 1930s President Karl Taylor Compton and Vice-President (effectively Provost) Vannevar Bush drastically reformed the curriculum by re-emphasizing the importance of "pure" sciences like physics and chemistry and reducing the work required in shops and drafting. Despite the difficulties of the Great Depression, the reforms "renewed confidence in the ability of the Institute to develop leadership in science as well as in engineering."[16] The expansion and reforms thus cemented MIT's academic reputation on the eve of World War II by attracting scientists and researchers who would later make significant contributions in the Radiation Laboratory, Instrumentation Laboratory, and other defense-related research programs.

MIT was drastically changed by its involvement in military research during World War II. Bush was appointed head of the enormous Office of Scientific Research and Development and directed funding to only a select group of universities, including MIT.[17][18] During the war and in the post-war years, this government-sponsored research contributed to a fantastic growth in the size of the Institute's research staff and physical plant as well as placing an increased emphasis on graduate education.[19]

As the Cold War and Space Race intensified and concerns about the technology gap between the U.S. and the Soviet Union grew more pervasive throughout the 1950s and 1960s, MIT's involvement in the military-industrial complex was a source of pride on campus.[20][21] However, by the late 1960s and early 1970s, intense protests by student and faculty activists (an era now known as "the troubles")[22] against the Vietnam War and MIT's defense research required that the MIT administration to divest itself from what would become the Charles Stark Draper Laboratory and move all classified research off-campus to the Lincoln Laboratory facility.

Facilities

MIT's 168-acre (0.7 km²) Cambridge campus spans approximately a mile of the Charles River front. The campus is divided roughly in half by Massachusetts Avenue, with most dormitories and student life facilities to the west and most academic buildings to the east. The bridge closest to MIT is the Harvard Bridge, which is marked off in the fanciful unit – the Smoot. The Kendall MBTA Red Line station is located on the far northeastern edge of the campus in Kendall Square. The Cambridge neighborhoods surrounding MIT are a mixture of high tech companies occupying both modern office and rehabilitated industrial buildings as well as socio-economically diverse residential neighborhoods.

MIT buildings all have a number (or a number and a letter) designation and most have a name as well.[23] Typically, academic and office buildings are referred to only by number while residence halls are referred to by name. The organization of building numbers roughly corresponds to the order in which the buildings were built and their location relative (north, west, and east) to the original, center cluster of Maclaurin buildings. Many are connected above ground as well as through an extensive network of underground tunnels, providing protection from the Cambridge weather. MIT also owns commercial real estate and research facilities throughout Cambridge and the greater Boston area.

MIT's on-campus nuclear reactor is the second largest university-based nuclear reactor in the United States. The high visibility of the reactor's containment building in a densely populated area has caused some controversy,[24] but MIT maintains that it is well-secured.[25] Other notable campus facilities include a pressurized wind tunnel, a towing tank for testing ship and ocean structure designs, and a low-emission cogeneration plant that serves most of the campus electricity and heating requirements. MIT's campus-wide wireless network was completed in the fall of 2005 and consists of nearly 3,000 access points covering 9,400,000 square feet (873,288.6 m²) of campus.[26]

Architecture

As MIT's school of architecture was the first in the United States,[27] it has a history of commissioning progressive, if stylistically inconsistent, buildings.[28] The first buildings constructed on the Cambridge campus, completed in 1916, are known officially as the Maclaurin buildings after Institute president Richard Maclaurin who oversaw their construction. Designed by William Welles Bosworth, these imposing buildings were built of concrete, a first for a non-industrial—much less university—building in the U.S.[29] The utopian City Beautiful movement greatly influenced Bosworth's design which features the Pantheon-esque Great Dome, housing the Barker Engineering Library, which overlooks Killian Court, where annual Commencement exercises are held. The friezes of the limestone-clad buildings around Killian Court are engraved with the names of important scientists and philosophers. The imposing Building 7 atrium along Massachusetts Avenue is regarded as the entrance to the Infinite Corridor and the rest of the campus.

Alvar Aalto's Baker House (1947), Eero Saarinen's Chapel and Auditorium (1955), and I.M. Pei's Green, Dreyfus, Landau, and Weisner buildings represent high forms of post-war modern architecture. More recent buildings like Frank Gehry's Stata Center (2004), Steven Holl's Simmons Hall (2002), and Charles Correa's Building 46 (2005) are distinctive amongst the Boston area's staid architecture[30] and serve as examples of contemporary campus "starchitecture."[28] These buildings have not always been popularly accepted; the Princeton Review includes MIT in a list of twenty schools whose campuses are "tiny, unsightly, or both." [31]

Organization

MIT is "a university polarized around science, engineering, and the arts."[32] MIT has five schools (Science, Engineering, Architecture and Planning, Management, and Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences) and one college (Whitaker College of Health Sciences and Technology), but no schools of law or medicine.[33]

MIT is governed by a 78-member board of trustees known as the MIT Corporation[34] which approve the budget, degrees, and faculty appointments as well as electing the President.[35] MIT's endowment and other financial assets are managed through a subsidiary MIT Investment Management Company (MITIMCo).[36] The chair of each of MIT's 32 academic departments reports to the dean of that department's school, who in turn reports to the Provost under the President. However, faculty committees assert substantial control over many areas of MIT's curriculum, research, student life, and administrative affairs.[37]

MIT students refer to both their majors and classes using numbers alone. Majors are numbered in the approximate order of when the department was founded; for example, Civil and Environmental Engineering is Course I, while Nuclear Science & Engineering is Course XXII.[38] Students majoring in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, the most popular department, collectively identify themselves as "Course VI." MIT students use a combination of the department's course number and the number assigned to the class number to identify their subjects; the course which many American universities would designate as "Physics 101" is, at MIT, simply "8.01."[39]

Classes

MIT has an extensive core curriculum required of all undergraduates called the General Institute Requirements (GIRs). The science requirement, generally completed during freshman year as prerequisites for classes in science and engineering majors, comprises two semesters of physics classes covering Classical Mechanics and E&M, two semesters of math covering single variable calculus and multivariable calculus, one semester of chemistry, and one semester of biology. Undergraduates are required to take a laboratory class in their major, eight Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences (HASS) classes (at least three in a concentration and another four unrelated subjects), and non-varsity athletes must also take four physical education classes.

Collaborations

MIT historically pioneered research collaborations between industry and government.[40][41] Fruitful collaborations with industrialists like Alfred P. Sloan and Thomas Alva Edison led President Compton to establish an Office of Corporate Relations and an Industrial Liaison Program in the 1930s and 1940s that now allows over 600 companies to license research and consult with MIT faculty and researchers.[42] As several MIT leaders served as Presidential scientific advisers since 1940,[43] MIT established a Washington Office in 1991 to continue to lobby for research funding and national science policy.[44]

Traditions

MIT faculty and students value highly meritocracy and technical proficiency. MIT has never awarded an honorary degree nor does it award athletic scholarships, ad eundem degrees, or Latin honors upon graduation. It does, on rare occasions, award honorary professorships; Winston Churchill was so honored in 1949 and Salman Rushdie in 1993.[45]

Brass Rat

Many MIT students and graduates wear a large, heavy, distinctive class ring known as the "Brass Rat." Originally created in 1929, the ring's official name is the "Standard Technology Ring." The undergraduate ring design (a separate graduate student version exists, as well) varies slightly from year to year to reflect the unique character of the MIT experience for that class, but always features a three-piece design, with the MIT seal and the class year each appearing on a separate face, flanking a large rectangular bezel bearing an image of a beaver.

Student Life

Activities

MIT has over 380 recognized student activity groups,[46] including a campus radio station, The Tech student newspaper, the "world's largest open-shelf collection of science fiction" in English, model railroad club, a vibrant folk dance scene, weekly screenings of popular films by the Lecture Series Committee, and an annual entrepreneurship competition.

MIT's Independent Activities Period is a four-week long "term" offering hundreds of optional classes, lectures, demonstrations, and other activities throughout the month of January between the Fall and Spring semesters. Some of the most popular recurring IAP activities are the 6.270, 6.370, and MasLab competitions, the annual "mystery hunt", and Charm School.

Many MIT students also engage in "hacking," which encompasses both the physical exploration of areas that are generally off-limits (such as rooftops and steam tunnels), as well as elaborate practical jokes. Recent hacks have included the theft of Caltech's cannon,[47] reconstructing a Wright Flyer atop the Great Dome,[48] and adorning the John Harvard statue with the Master Chief's Spartan Helmet.[49]

The MIT Blackjack Team was a group of students and ex-students from MIT but also including several from Harvard University, who utilized card-counting techniques and more sophisticated strategies to beat casinos at blackjack. The team and its successors operated from 1979 through the beginning of the twentyfirst century. The origin of blackjack play at MIT was a mini-course called 'How to Gamble if You Must', taught in January 1979 at MIT over what is known as Independent Activities Period (IAP). A number of MIT students from living groups in the Burton House dorm known as Burton V and Conner III, who often played penny-ante poker with each other, attended this course and learned about blackjack and card counting methods. They then tried out their techniques in casinos in Atlantic City. Despite initial failures, two of them continued the course and, with the help of a Harvard graduate, formed a professional team who went on to make a fortune in Las Vegas. Stories, some true and some fictionalized, about a few of the players from the MIT Blackjack Team formed the basis of the New York Times bestsellers, Bringing Down the House and Busting Vegas, written by Ben Mezrich.

Athletics

MIT's student athletics program offers 41 varsity-level sports, the largest program in the nation.[50][51] They participate in the NCAA's Division III, the New England Women's and Men's Athletic Conference, the New England Football Conference, and NCAA's Division I and Eastern Association of Rowing Colleges (EARC) for crew. They fielded several dominant intercollegiate Tiddlywinks teams through 1980s, winning national and world championships.[52] MIT teams have won or placed highly in national championships in pistol, track and field, swimming and diving, cross country, crew, fencing, and water polo. MIT has produced 128 Academic All-Americans, the third largest membership in the country for any division and the highest number of members for Division III.[53]

The Institute's sports teams are called the Engineers, their mascot since 1914 being a beaver, "nature's engineer." Lester Gardner, a member of the Class of 1898, provided the following justification:

| “ | The beaver not only typifies the Tech, but his habits are particularly our own. The beaver is noted for his engineering and mechanical skills and habits of industry. His habits are nocturnal. He does his best work in the dark.[54] | ” |

Noted alumni

Many of MIT's over 110,000 alumni and alumnae have had considerable success in scientific research, public service, education, and business. 27 MIT alumni have won the Nobel Prize and 37 have been selected as Rhodes Scholars.[55]

Alumni in American politics and public service include Chairman of the Federal Reserve Ben Bernanke, New Hampshire Senator John E. Sununu, U.S. Secretary of Energy Samuel Bodman, MA-1 Representative John Olver, CA-13 Representative Pete Stark. MIT alumni in international politics include British Foreign Minister David Miliband, former U.N. Secretary General Kofi Annan, former Iraqi Deputy Prime Minister Ahmed Chalabi, and former Prime Minister of Israel Benjamin Netanyahu.

MIT alumni founded or co-founded many notable companies, such as Intel, McDonnell Douglas, Texas Instruments, 3Com, Qualcomm, Bose, Raytheon, Koch Industries, Rockwell International, Genentech, and Campbell Soup.

MIT alumni have also led other prominent institutions of higher education, including the University of California system, Harvard University, Johns Hopkins University, Carnegie Mellon University, Tufts University, Northeastern University, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Tecnológico de Monterrey, and Purdue University. Although not alumni, former Provost Robert A. Brown is President of Boston University, former Provost Mark Wrighton is Chancellor of Washington University in St. Louis, and former Professor David Baltimore was President of Caltech.

More than one third of the United States' manned spaceflights have included MIT-educated astronauts, among them Buzz Aldrin (Sc. D XVI '63), more than any university excluding the United States service academies.[56]

Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin, ScD XVI'63

Former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan, MS XV'72

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica, volume 4, p. 292: "[MIT] was a pioneer in introducing as a feature of its original plans laboratory instruction in physics, mechanics, and mining."

- ↑ TheCenter Research University Data (2005). Retrieved 2006-12-15.

- ↑ "Three from MIT win top U.S. science, technology honors", MIT News Office, July 19, 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-20.

- ↑ MIT Office of Provost, Institutional Research. MIT MacArthur Fellows. Retrieved 2006-12-16.

- ↑ Bank of Boston Economics Department (March 1997). MIT: The Impact of Innovation. Retrieved 2006-10-04.

- ↑ MIT Facts 2007: Mission and Origins. Retrieved 2006-07-18.

- ↑ Lewis, Warren K. and Ronald H. Rornett, C. Richard Soderberg, Julius A. Stratton, John R. Loofbourow, et al (December 1949). Report of the Committee on Educational Survey (Lewis Report). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, p. 8. Retrieved 2006-10-04.

- ↑ Barton's philosophy for the institute was for "the teaching, not of the manipulations done only in the workshop, but the inculcation of all the scientific principles which form the basis and explanation of them;" The Founding of MIT, cites (1) Letter, William Barton Rogers to Henry Darwin Rogers, March 13, 1846, William Barton Rogers Papers (MC 1), Institute Archives & Special Collections, MIT Libraries.

- ↑ Andrews, Elizabeth, Nora Murphy, and Tom Rosko(2004), William Barton Rogers: MIT's Visionary Founder (Charter, laboratory instruction, first classes in Mercantile building)

- ↑ The history montage at the Kendall/MIT T-stop

- ↑ National Selection Committee Ballot - Power of the NSC. Retrieved 23 November, 2005.

- ↑ "Tech Alumni Holds Reunion. Record attendance, novel features. Cooperative plan with Harvard announced by Pres. Maclaurin. Gov. Walsh Brings Best Wishes of the State.", Boston Daily Globe, 1914-01-11, p. 117.

Maclaurin quoted: "in future Harvard agrees to carry out all its work in engineering and mining in the buildings of Technology under the executive control of the president of Technology, and, what is of the first importance, to commit all instruction and the laying down of all courses to the faculty of Technology, after that faculty has been enlarged and strengthened by the addition to its existing members of men of eminence from Harvard's Graduate School of Applied Science." - ↑ "Harvard-Tech Merger. Duplication of Work to be Avoided in Future. Instructors Who WIll Hereafter be Members of Both Faculties", Boston Daily Globe, 1914-01-25, p. 47.

- ↑ Canceled by a 1917 State Judicial Court decision.Harvard Division of Engineering and Applied Sciences.

- ↑ The "New Tech" (2006-09-08). Retrieved 2006-12-01.

- ↑ Report of the Committee on Educational Survey, page 13. Retrieved November 6, 2007.

- ↑ Leslie, Stuart (2004-04-15). The Cold War and American Science: The Military-Industrial-Academic Complex at MIT and Stanford. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-07959-1.

- ↑ Zachary, Gregg (1997-09-03). Endless Frontier: Vannevar Bush, Engineer of the American Century. Free Press. ISBN 0-684-82821-9.

- ↑ Report of the Committee on Educational Survey, page 13

- ↑ More Emphasis on Science Vitally Needed to Educate Man for A Confused Civilization (1958-02-14). Retrieved 2006-11-05.

- ↑ Iron Birds Caged in Building 7 Lobby: Missiles on Display Here (1958-02-25). Retrieved 2006-11-05.

- ↑ "At a critical time in the late 1960s, Johnson stood up to the forces of campus rebellion at MIT. Many university presidents were destroyed by the troubles. Only Edward Levi, University of Chicago president, had comparable success guiding his institution to a position of greater strength and unity after the turmoil." David Warsh (June 1, 1999). A tribute to MIT's Howard Johnson. Boston Globe. Retrieved 2007-04-04.

- ↑ MIT Whereis. Retrieved 2007-08-05.

- ↑ ABC News. Loose Nukes: A Special Report. Retrieved 2007-04-14.

- ↑ MIT News Office (2005-10-13). MIT Assures Community of Research Reactor Safety. Retrieved 2006-10-05.

- ↑ MIT maps wireless users across campus (2005-11-04). Retrieved 2007-03-03.

- ↑ MIT Architecture: Welcome. Retrieved 2007-04-04.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Starchitecture on Campus (2004-02-22). Retrieved 2006-10-24.

- ↑ {{{Last}}}, {{{First}}} ({{{Year}}})

- ↑ "Boston isn’t yet fully embracing contemporary architecture... it’s far riskier to put an unapologetically modern building in the historic Back Bay, not far from the neighborhood’s Victorian town houses and Gothic Revival columns."Rachel Strutt (February 11, 2007). Stained Glass?. Retrieved 2007-04-04.

- ↑ " 2007 361 Best College Rankings: Quality of Life: Campus Is Tiny, Unsightly, or Both. Princeton Review (2006). Retrieved 2006-10-09. It should be noted in this regard that the size of the campus is considerable.

- ↑ James R. Killian (1949-04-02). The Inaugural Address. Retrieved 2006-06-02.

- ↑ The Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technonolgy (HST) offers joint MD, MD-PhD, or Medical Engineering degrees in collaboration with Harvard Medical School.

Harvard-MIT HST Academics Overview. Retrieved 2007-08-05. - ↑ MIT Corporation. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- ↑ A Brief History and Workings of the Corporation. Retrieved 2006-11-02.

- ↑ MIT Investment Management Company. Retrieved 2007-01-08.

- ↑ Rafael L. Bras (2004-2005). Reports to the President, Report of the Chair of the Faculty. Retrieved 2006-12-01.

- ↑ MIT Education. Retrieved 2006-12-03.

- ↑ Course numbers are traditionally presented in Roman numerals, e.g. Course XVIII for mathematics. Starting in 2002, the Bulletin (MIT's course catalog) started to use Arabic numerals. Usage outside of the Bulletin varies, both Roman and Arabic numerals being used). This section follows the Bulletin's usage.

- ↑ "MIT for a long time... stood virtually alone as a university that embraced rather than shunned industry."

(August 8, 1987) A Survey of New England: A Concentration of Talent. The Economist. - ↑ "The war made necessary the formation of new working coalitions... between these technologists and government officials. These changes were especially noteworthy at MIT."

Edward B. Roberts (1991). "An Environment for Entrepreneurs", MIT: Shaping the Future. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. ISBN 0262631451. - ↑ MIT ILP - About the ILP. Retrieved 2007-03-17.

- ↑ Nearly half of all US Presidential science advisors have had ties to the Institute. MIT News Office (May 2, 2001). Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- ↑ MIT Washington Office. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- ↑ Stevenson, Daniel C., "Rushdie Stuns Audience 26-100", MIT Tech, 1993-11-30, pp. 1.

- ↑ MIT Association of Student Activities. Retrieved 2006-11-01.

- ↑ Howe & Ser Moving Co.. Retrieved 2007-04-04.

- ↑ MARCELLA BOMBARDIERI. "Mit Pranksters Wing It For Wright Celebration", Boston Globe, December 18, 2003.

- ↑ MIT Hackers & Halo 3. The Tech. Retrieved 2007-09-25.

- ↑ MIT Facts 2007: Athletics and Recreation. Retrieved 2007-02-14.

- ↑ Varisty Sports fact sheets. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

- ↑ Shapiro, Fred (1972-04-25). MIT's World Champions pp. 7. The Tech. Retrieved 2006-10-04.

- ↑ MIT Facts 2007: Athletics and Recreations. Retrieved 2007-02-14.

- ↑ MIT '93 Brass Rat. Retrieved 2007-03-23.

- ↑ MIT Office of Institutional Research. Awards and Honors. Retrieved 2006-11-05.

- ↑ Notable Alumni. Retrieved 2006-11-04.

Further reading

- See the bibliography maintained by MIT's Institute Archives & Special Collections

- Leslie, Stuart W. (1994). The Cold War and American Science: The Military-Industrial-Academic Complex at MIT and Stanford. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-07959-1.

- Mitchell, William J. (2007). Imagining MIT: Designing a Campus for the Twenty-First Century. The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-13479-8.

- Snyder, Benson R. (1973). The Hidden Curriculum. The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-69043-0.

- Peterson, T. F. (2003). Nightwork: A History of Hacks and Pranks at MIT. The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-66137-9.

- Stratton, Julius Adams and Loretta H. Mannix (2005). Mind and Hand: The Birth of MIT. The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-19524-9.

- Prescott, Samuel C. (1954). When M.I.T. Was "Boston Tech," 1861-1916. Technology Press. ISBN 978-0-262-66139-3.

- Jarzombek, Mark (2003). Designing MIT: Bosworth's New Tech. Northeastern University Press. ISBN 1-55553-619-0.

- Simha, O. Robert (2003). MIT Campus Planning,: An Annotated Chronology. The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-69294-6.

External links

- MIT, official web site

- MyMIT, admissions web site

- MIT Alumni Association

- MIT OpenCourseWare, Free online publication of nearly all MIT course materials

- The Tech, student newspaper, the world's first newspaper on the web

- Tech Talk, MIT's official newspaper

- Technology Review, mass market technology and alumni magazine

- MIT Press, university press & publisher

- MIT World video streams of public lectures and symposia

- MIT Maps

- Early Maps of both the Boston and Cambridge Campuses maintained by MIT's Institute Archives & Special Collections

- Maps and aerial photos

- Street map from Google Maps or Yahoo! Maps

- Topographic map from TopoZone

- Satellite image from Google Maps or Microsoft Virtual Earth

| Association of American Universities | |

|---|---|

| Public | Arizona • Buffalo (SUNY) • UC Berkeley • UC Davis • UC Irvine • UCLA • UC San Diego • UC Santa Barbara • Colorado • Florida • Illinois • Indiana • Iowa • Iowa State • Kansas • Maryland • Michigan • Michigan State • Minnesota • Missouri • Nebraska • North Carolina • Ohio State • Oregon • Penn State • Pittsburgh • Purdue • Rutgers • Stony Brook (SUNY) • Texas • Texas A&M • Virginia • Washington • Wisconsin |

| Private | |

| Canadian | McGill • Toronto |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.